Stability of a Unipolar World 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridling the International Trade of Catastrophic Weaponary

ARTICLES BRIDLING THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF CATASTROPHIC WEAPONRY BARRY KELLMAN* "It is fashionable among industrialized nations to deplore acquisi- tion of high-technology weapons by developing nations, but this moralistic stand is akin to drug pushers shedding tears about the weaknesses of drug addicts."' TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................... 757 I. Definition of Catastrophic Weaponry .............. 759 A. Nuclear Weapons ........................... 759 B. Chemical Weapons and Toxins ................ 762 C. Biological Weapons ......................... 763 D. Ballistic Missiles ............................ 764 II. Theories of Nonproliferation .................... 767 A. Deterring Nations from Using Weapons or Preventing Weapons Acquisition ............... 768 1. Realpolitik ............................. 768 * Professor of Law, DePaul University College of Law, J.D., Yale University, 1976. The author serves as a consultant to the Defense Nuclear Agency on issues relating to the legal implementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, to the Department of Energy on issues relating to inspection procedures under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and was chairman of an international committee of legal experts that prepared a Manualfor NationalImplementation of the Chemical Weapons Convention on behalf of the international Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in The Hague. The author is grateful for the support received from the United States Institute of Peace during the research and preparation of this Article. The author is also deeply appreciative of the reviews and comments from M. Cherif Bassiouni, Jonathan Fox, David Gualtieri, David Koplow, Jessica Stern, and Edward Tanzman. 1. C. Raja Mohan & K. Subrahmanyam, High-Technology Weapons in the Developing Work!, in NEw TECHNOLOGIES FOR SECURrIYAND ARMs CONTROL THREATs AND PRoMISE 229,229-30 (Eric H. -

"Wohlstand Für Alle": Ludwig Erhard Und Die Soziale Marktwirtschaft

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mann, Gerald H. Working Paper 60 Jahre "Wohlstand für alle": Ludwig Erhard und die Soziale Marktwirtschaft Arbeitspapiere der FOM, No. 74 Provided in Cooperation with: FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie & Management gGmbH Suggested Citation: Mann, Gerald H. (2019) : 60 Jahre "Wohlstand für alle": Ludwig Erhard und die Soziale Marktwirtschaft, Arbeitspapiere der FOM, No. 74, ISBN 978-3-89275-096-3, MA Akademie Verlags- und Druck-Gesellschaft mbH, Essen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/201508 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Nr. 60 Jahre „Wohlstand für alle“ 74 Ludwig Erhard und die Soziale Marktwirtschaft ~ Gerald Mann Arbeitspapiere der FOM Gerald Mann 60 Jahre „Wohlstand für alle“ Ludwig Erhard und die Soziale Marktwirtschaft Arbeitspapiere der FOM, Nr. -

Öffentliche Anhörung „Neustart Für Die Wirtschaft in Deutschland Und Europa“ Am 27

Deutscher Bundestag: Öffentliche Anhörung „Neustart für die Wirtschaft in Deutschland und Europa“ am 27. Mai 2020 Prof. Dr. Max Otte 1 Öffentliche Anhörung im Deutschen Bundestag: „Neustart für die Wirtschaft in Deutschland und Europa“ am 27. Mai 2020 – Stellungnahme Prof. Dr. Max Otte Deutscher Bundestag: Öffentliche Anhörung „Neustart für die Wirtschaft in Deutschland und Europa“ am 27. Mai 2020 von Prof. Dr. Max Otte Inhalt 0 Zusammenfassung ........................................................................................................................... 4 1 Die Situation vor Corona ................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Niedrig- und Negativzinsen, hohe Schulden ........................................................................... 5 1.2 Geringes Produktivitätswachstum .......................................................................................... 6 1.3 Abstieg der Mittelschicht, Aufblähung der Asset-Märkte und ungleiche Vermögensverteilung sowie Populismus als globales Phänomen ...................................................... 8 1.4 Divergenzen in der Eurozone ................................................................................................ 10 1.5 Die Deutschen: die armen Verwandten der Eurozone ......................................................... 11 1.6 Die Wirtschaft steuerte bereits vor Corona auf eine Rezession zu ....................................... 12 1.7 Der Reset des Weltfinanzsystems war bereits -

Germany, Afghanistan, and the Process of Decision Making in German Foreign Policy: Constructing a Framework for Analysis

ABSTRACT Title of Document: GERMANY, AFGHANISTAN, AND THE PROCESS OF DECISION MAKING IN GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY: CONSTRUCTING A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS Karin L. Johnston, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor George Quester, Department of Government and Politics Germany’s emerging role as a supplier of security by contributing troops to out-of-area operations is a significant change in post-unification German foreign and security policy, and yet few studies have sought to explain how the process of decision making also has changed in order to accommodate the external and domestic factors that shape policy preferences and outcomes. The dissertation addresses these theoretical gaps in foreign policy analysis and in German foreign and security policy studies by examining the decision-making process in the case of Afghanistan from 2001–2008, emphasizing the importance of institutional structures that enable and constrain decision-makers and then gathering the empirical evidence to construct a framework for analyzing German foreign policy decision making. The dynamics of decision-making at the state level are examined by hypothesizing about the role of the chancellor in the decision-making process— whether there has been an expansion of chancellorial power relative to other actors— and about the role of coalition politics and the relative influence of the junior coalition partner in coalition governments. Results indicate that there are few signs that federal chancellors dominate or otherwise control decision-making outcomes, and that coalition politics remain a strong explanatory factor in the process that shapes the parameters of policy choices. The dissertation highlights the central role of the Bundestag, the German parliament. -

The “European Stability Mechanism” (ESM) As a New Enabling Act

No 18/19 8 May 2012 CurrentCurrent Concerns Concerns «ESM Dossier » Page I The “European Stability Mechanism” (ESM) as a new Enabling Act for the suffocation of European states The “European Freetrade Association” (EFTA) would be the necessary and reasonable alternative by Dr phil. René Roca The “European Freetrade Association” an Coal and Steel Community”, had put And still the OEEC had started with the (EFTA) was founded by 7 Western Eu- the six founding states on the wrong, i.e. will to lead Europe back to the democratic ropean countries including Switzerland supranational, track. Some “High Com- path by the “rule of law”, out of the ruins in 1960. Today the EFTA is left with mission”, endorsed and directed by the left by the second world war. This had only 4 remaining members, namely Ice- USA, had started to claim important ele- only been possible thanks to a foundation land, Norway, Switzerland and Liech- ments of national states’ sovereign rights. based on natural law and the intention to tenstein. In the aftermath of the second Today the EU is a “state union” held to- strengthen social market economy in a de- World War, the European states had in- gether by various treaties. With the Lisbon central, federal society. A global determi- itially aimed for a solid and sustainable treaty the EU elite had recently imposed nation had emanated from this focusation foundation of their economic development a kind of “constitution” on the member of forces to leave all totalitarian ideas in with a big free trade zone built around states, without discussion or voting of the Europe behind once and for all, with the the “Organization for European Eco- affected cirizens, and this treaty is now UN charter and the declaration of human nomic Co-operation” (OEEC). -

Zusammenstellung Der Stellungnahmen Der Sachverständigen Öffentliche Anhörung „Neustart Für Die Wirtschaft in Deutschland Und Europa“ Am Mittwoch, Den 27

19. Wahlperiode Ausschuss für Wirtschaft und Energie Ausschussdrucksache 19(9)639 26. Mai 2020 Zusammenstellung der Stellungnahmen der Sachverständigen Öffentliche Anhörung „Neustart für die Wirtschaft in Deutschland und Europa“ am Mittwoch, den 27. Mai 2020 Prof. Dr. Justus Haucap Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorfer Institut für Wettbewerbsökonomie (DICE) A-Drs. 19(9)636 Prof. Dr. Michael Eilfort Stiftung Marktwirtschaft A-Drs. 19(9)638 Dr. Volker Treier Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag e.V. (DIHK) A-Drs. 19(9)634 Prof. Dr. Jens Südekum Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf (HHU) A-Drs. 19(9)628 Dr. Andrä Gärber Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e.V. A-Drs. 19(9)629 Prof. Dr. Max Otte Unternehmer, Investor und Philanthrop - Ehemaliger ordentlicher Professor für quantitative und qualitative Unternehmensanalyse und -diagnose an der Universität Graz, ordentlicher Professor a.D. für internationale und allgemeine BWL an der Hochschule Worms A-Drs. 19(9)632 Prof. Dr. Gabriel Felbermayr Institut für Weltwirtschaft (IfW Kiel) A-Drs. 19(9)631 Stefan Körzell Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB) A-Drs. 19(9)633 Dr. Patrick Graichen Agora Energiewende A-Drs. 19(9)635 26. Mai 2020 Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf 40204 Düsseldorf Düsseldorf Institute for Competition Economics – DICE Wirtschafts- wissenschaftliche Fakultät DICE Deutscher Bundestag Ausschuss für Wirtschaft und Energie Prof. Dr. Jens Südekum Platz der Republik 1 11011 Berlin Telefon +49 211 81 11622 [email protected] Düsseldorf, 25.5.2020 Stellungnahme zur Öffentlichen Anhörung Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf „Neustart für die Wirtschaft in Deutschland und Europa“ Universitätsstraße 1 40225 Düsseldorf Gebäude 24.31 Ebene 01 Raum 34 www.dice.hhu.de www.hhu.de Deutschland und Europa stehen vor enormen Herausforderungen Die Coronakrise wird zur tiefsten globalen ökonomischen Krise seit dem Ende der 1920er Jahre führen. -

Media Discourses of Nation and Cultural Differences: a Case Study of Westdeutscher Rundfunk

Media discourses of nation and cultural differences: a case study of Westdeutscher Rundfunk Krtalić Muiesan, Iva Doctoral thesis / Disertacija 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:121978 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works SVEUČILIŠTE U ZADRU POSLIJEDIPLOMSKI SVEUČILIŠNI STUDIJ HUMANISTIČKE ZNANOSTI Iva Krtalić Muiesan MEDIA DISCOURSES OF NATION AND CULTURAL DIFFERENCES: A CASE STUDY OF WESTDEUTSCHER RUNDFUNK Doktorski rad Zadar, 2019. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZADRU POSLIJEDIPLOMSKI SVEUČILIŠNI STUDIJ HUMANISTIČKE ZNANOSTI Iva Krtalić Muiesan MEDIA DISCOURSES OF NATION AND CULTURAL DIFFERENCES: A CASE STUDY OF WESTDEUTSCHER RUNDFUNK Doktorski rad Mentorica Izv. prof. dr. sc. Senka Božić-Vrbančić Zadar, 2019. UNIVERSITY OF ZADAR BASIC DOCUMENTATION CARD I. Author and study Name and surname: Iva Krtalić Muiesan Name of the study programme: Postgraduate doctoral study in Humanities Mentor: Associate professor Senka Božić-Vrbančić, PhD Date of the defence: May 8th, 2019 Scientific area and field in which the PhD is obtained: Humanities, Interdisciplinary humanities II. Doctoral dissertation Title: Media discourses of nation and cultural differences: A case study of Westdeutscher Rundfunk UDC mark: 316.774:654.1>(430) Number of pages: 311 Number of pictures/graphical representations/tables: 7/0/0 Number of notes: 78 Number of used bibliographic units and sources: 377 Number of appendices: 2 Language of the doctoral dissertation: English III. Expert committees Expert committee for the evaluation of the doctoral dissertation: 1. Associate Professor Tomislav Pletenac, PhD, chair 2. -

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Heading Into the Mainstream? Reviewing a Year of the Afd in the German Parliament Page 1 of 4

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Heading into the mainstream? Reviewing a year of the AfD in the German parliament Page 1 of 4 Heading into the mainstream? Reviewing a year of the AfD in the German parliament Almost one year has passed since the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) was elected to the Bundestag in the 2017 German federal elections. Julian Göpffarth looks back on what has happened since, and how events have shaped both the AfD and German society. Media coverage in Germany has been dominated in recent days by far-right violence in the city of Chemnitz. Embedded in large crowds of anti-refugee and anti-immigration protests, the pictures offered shocking images of neo-Nazis reminiscent of the violent outbreaks in Rostock, Solingen and Hoyerswerda almost 30 years ago. The self-confidence visible in many of the protagonists, the support of large sections of the local population, and the entanglement of the protests with local institutions in Chemnitz, reflects the increased reach and normalisation of far-right positions in parts of the German population. An important milestone for the institutionalisation and spread of far-right positions was the AfD’s election to the Bundestag with 12.6 per cent of the vote on 24 September last year. While Chemnitz has yet again shifted the attention to the far-right’s strength in economically weak areas in East Germany, the AfD’s success in 2017 and its stable position in polls all over Germany suggests that far-right ideas chime with a substantial number of German citizens. -

Die Finanzkrise, Die Ökonomen, Der „Crashprophet“ Und Die Wissenschaft Von Der Ökonomie

DOI: 10.1524/jbwg.2011.0009 Heading: Kölner Vorträge Die Finanzkrise, die Ökonomen, der „Crashprophet“ und die Wissenschaft von der Ökonomie Von Max Otte (Worms)1 I. Die Finanzkrise und die Ökonomen Am 15. September 2008 meldete die U.S.-amerikanische Investmentbank Lehman Brothers Insolvenz an. Es folgte die schwerste Finanzkrise seit 1929 – eine Liquiditäts- und vor allem Solvenzkrise der großen kapitalmarktorientierten Banken, vor allem in den westlichen Industrienationen. Das Misstrauen der Banken untereinander verursachte ein Einfrieren der Kreditmärkte und gravierende realwirtschaftliche Konsequenzen. In Folge mussten viele Banken durch massive Eigenkapitalhilfen gestützt werden, einige wurden abgewickelt, zerschlagen oder reorganisiert; die Notenbanken gaben Liquidität un- gekannten Ausmaßes in den Markt, und viele Industrienationen stützten ab Herbst 2008 die Konjunktur mit massiven Konjunkturprogrammen. Insgesamt beliefen sich die Kosten bis Ende 2009 auf ungefähr 10,5 Billionen Dollar oder 20 Prozent des Weltsozialprodukts. Rund 1,6 Millionen Dollar mussten bei den Banken abgeschrieben werden, 4,65 Billionen betrug der Wertverlust von Immobilien und 4,2 Billionen Dollar (oder knapp fünf Prozent des Weltsozialproduktes) gingen auf verringertes Wirtschaftswachstum zurück.2 Als Folge stiegen die Haushaltsdefizite massiv, so dass im Frühjahr 2010 eine Staatsschul- denkrise vor allem in den südeuropäischen Ländern sowie spekulative Attacken auf den Euro folgten. Dabei sahen die Haushalte der primären Verursachernationen USA und Groß- 1 Der Verfasser dankt Toni Pierenkemper für die Einladung zu den Kölner Vorträgen zur Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte. Dies ist der erste offizielle Vortrag an seiner Alma Mater, die von 1984 bis 1989 Ort vieler angeregter Diskussionen, des Lernens, neuer Freundschaften sowie des Aufbruchs ins Er- wachsenenleben war. -

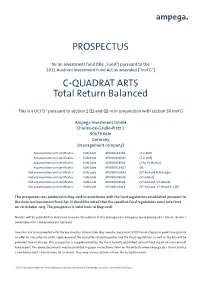

PROSPECTUS C-QUADRAT ARTS Total Return Balanced

PROSPECTUS for an investment fund (the „Fund“) pursuant to the 2011 Austrian Investment Fund Act as amended (“InvFG“) C-QUADRAT ARTS Total Return Balanced This is a UCITS 1 pursuant to section 2 (1) and (2) in in conjunction with section 50 InvFG Ampega Investment GmbH Charles-de-Gaulle-Platz 1 50679 Köln Germany (management company) Accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000634704 (T in EUR) Accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A0XH66 (T in CHF) Accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A06P08 (T für PL (Polen)) Accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A218G7 (H) Full accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A1H6A3 (VT-Ausland PLN hedge) Full accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A08EU8 (VT-Inland) Full accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A08EV6 (VT-Ausland, VT-Inland) Full accumulation unit certificates: ISIN-Code AT0000A139C4 (VT-Ausland, VT-Inland in CZK) This prospectus was produced in May 2018 in accordance with the fund regulations established pursuant to the Austrian Investment Fund Act. It should be noted that the specified fund regulations came into force on 26 October 2015. The prospectus is valid from 16 May 2018. Notices will be published in electronic form on the website of the management company, www.ampega.de > Unser Service > Fondsübersicht > Fondsname (in German). Investors are to be provided with the key investor information (key investor document, KID) free-of-charge in good time prior to an offer to subscribe for units. Upon demand the currently valid prospectus and the fund regulations as well as the KID will be provided free-of-charge. This prospectus is supplemented by the most recently published annual fund report or semi-annual fund report. -

Portfolio Manager's Review, Interview with Professor Max Otte

ORTFOLIO ANAGER S EVIEW P M ’ R A Monthly Publication of BeyondProxy LLC www.manualofideas.com [email protected] October 27, 2009 When asked how he became so successful, Buffett answered: “we read hundreds and hundreds of annual reports every year.” Edited by the Manual of Ideas Research Team THE EUROPEAN VALUE ISSUE “If our efforts can further the goals of our members by giving them a discernible edge over other market participants, we have succeeded.” ► Snapshot of 100 European companies Top Five Ideas In This Report ► 24 companies profiled by MOI research team AstraZeneca ► Proprietary selection of Top 5 candidates for investment (NYSE: AZN, London: AZN) … p. 24 ► Plus: Exclusive Interview with Don Fitzgerald Diageo ► (NYSE: DEO, London: DGE) … p. 27 Plus: Exclusive Interview with Professor Max Otte InterContinental Hotels ► Plus: Exclusive Interview with Adam Steiner (NYSE: IHG, London: IHG) … p. 30 ► Plus: Exclusive Interview with Robert Vinall OMV (OTC: OMVKY, Vienna: OMV) p. 33 Royal Wessanen (OTC: KJWNY, Amster.: WES) p. 36 European companies mentioned in this issue include Also Inside ABB, Acergy, AEGON, Alcatel-Lucent, Allianz, Allied Irish Banks, Altana, Anglo American, ArcelorMittal, ARM Holdings, AstraZeneca, AXA, Editor’s Commentary …………….. p. 5 Babcock & Brown, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, Banco Santander, 100 European Candidates ……… p. 6 Bank of Ireland, Barclays, BG Group, BP, British American Tobacco, Company Profiles ……………… p. 24 British Sky Broadcasting, Cadbury, Carnival, CGG Veritas, CNH Global, Interview with Don Fitzgerald …. p. 95 Commerzbank, Continental, Credit Suisse, CRH, Delhaize, Interview with Professor Otte …. p. 98 Deutsche Telekom, Diageo, DSM, E.ON, Eni, Ericsson, Interview with Adam Steiner …. -

Inhalt / Abstracts / Autoren / Klassifizierungen

Inhalt I. Abhandlungen und Studien Reinhard Spree Einleitung................................................................................................................. 9 Martin Uebele Die Identifikation internationaler Konjunkturzyklen in disaggregierten Daten: Deutschland, Frankreich und Großbritannien, 1862-1913...................................... 19 Moritz Schularick 140 Years of Financial Crises: Old Dog, New Tricks......................................…... 45 Margrit Grabas Die Gründerkrise von 1873/79 – Fiktion oder Realität? Einige Überlegungen im Kontext der Weltfinanz- und Wirtschaftskrise von 2008/2009.................................................................................................................. 69 Alexander Nützenadel Städtischer Immobilienmarkt und Finanzkrisen im späten 19. Jahrhundert...…..... 97 Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich Vergleichende Aspekte der Großen Krisen nach 1929 und 2007..........................115 Toni Pierenkemper Von der Tulpenkrise zum Finanzmarktkollaps. Das Allgemeine im Besonderen.............................................................................139 II. Forschungs- und Literaturberichte Rolf Harald Stensland Resolving business and national interests in time of war. Fritz von Friedländer-Fuld and his German resources in Norway during the First World War................................................................……...........163 III. Kölner Vorträge Max Otte Die Finanzkrise, die Ökonomen, der „Crashprophet” und die Wissenschaft von der Ökonomie..................................................................................................191