Open PDF 185KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOUSE of COMMONS Exiting the European Union Committee

HOUSE OF COMMONS Exiting the European Union Committee Oral evidence: The progress of the UK’s negotiations on EU withdrawal, HC 372 Monday 3 September 2018, Brussels Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 4 September 2018. Members present: Hilary Benn (Chair); Sir Christopher Chope; Stephen Crabb; Richard Graham; Peter Grant; Andrea Jenkyns; Stephen Kinnock; Jeremy Lefroy; Mr Pat McFadden; Seema Malhotra; Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg; Emma Reynolds; Stephen Timms; Mr John Whittingdale. Questions 2537 - 2563 Witnesses I: Michel Barnier, Chief Negotiator, European Commission, and Sabine Weyand, Deputy Chief Negotiator, European Commission. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Michel Barnier and Sabine Weyand. Michel Barnier: Welcome once again. You are always welcome. Q2537 Chair: Michel, can I reciprocate on behalf of the Committee? It is very good to see you again. Can I begin by apologising that we had to let you down on the previous date when we were due to meet? We had certain important votes in Parliament that necessitated our attendance. Secondly, can I thank you very much for honouring the commitment you made to us the first time we met, that you would give evidence to the Committee on the record? Because as you are aware, today’s session is being recorded and will be published as an evidence session, so it is a slightly different format from our previous discussions. I understand entirely that you will want to check the English translation of what you said before the minutes are published and we realise that will take— Michel Barnier: Just to check that nothing is lost in translation. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Sir Christopher Chope Mr Peter Bone Mr William Wragg Dr Julian Lewis Richard Drax Henry Smith Line 3, Leave out from “Until” to End and Insert “Monday 22 February”

Wednesday 13 January 2021 Order Paper No.158: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Women and Equalities 12 noon Oral Questions: Prime Minister 12.30pm Urgent Questions, including on: Disruption to trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a result of the Northern Ireland Protocol (Minister for the Cabinet Office) May 2021 elections (Minister for the Cabinet Office) Ministerial Statements, including on: Mental Health Act reform (Secretary of State for Health and Social Care) 2 Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 Up to 20 Ten Minute Rule Motion: Covid- minutes 19 Financial Assistance (Gaps in Support) (Tracy Brabin) Until 7.00pm Financial Services Bill: Remaining Stages Until any hour* Business of the House (Today) (Motion) (*if the Business of the House Motion is agreed to) Up to one Sittings in Westminster Hall hour from the (Suspension) (No. 2) (Motion) commencement Business of the House (Private of proceedings Members’ Bills) (No. 9) (Motion) on the Business of the House (**if the Business of the House (Today) (Today) (Motion) is agreed to) Motion** No debate Statutory Instrument (Motion for approval) No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 3 Until 7.30pm or Adjournment Debate: Support for half an hour for small business during the covid-19 outbreak (Christine Jardine) WESTMINSTER HALL 9.30am Support for pupils’ education during school closures 11.00am Discharges into rivers (The sitting will be suspended from 11.30am to 2.30pm.) 2.30pm Online anonymity 4.00pm Desecration of war memorials 4.30pm The political situation in Kashmir 4 Wednesday 13 January 2021 OP No.158: Part 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 5 Chamber 16 Westminster Hall 18 Written Statements 19 Committees Meeting Today 28 Announcements 33 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 38 A. -

Thecoalition

The Coalition Voters, Parties and Institutions Welcome to this interactive pdf version of The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Please note that in order to view this pdf as intended and to take full advantage of the interactive functions, we strongly recommend you open this document in Adobe Acrobat. Adobe Acrobat Reader is free to download and you can do so from the Adobe website (click to open webpage). Navigation • Each page includes a navigation bar with buttons to view the previous and next pages, along with a button to return to the contents page at any time • You can click on any of the titles on the contents page to take you directly to each article Figures • To examine any of the figures in more detail, you can click on the + button beside each figure to open a magnified view. You can also click on the diagram itself. To return to the full page view, click on the - button Weblinks and email addresses • All web links and email addresses are live links - you can click on them to open a website or new email <>contents The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Edited by: Hussein Kassim Charles Clarke Catherine Haddon <>contents Published 2012 Commissioned by School of Political, Social and International Studies University of East Anglia Norwich Design by Woolf Designs (www.woolfdesigns.co.uk) <>contents Introduction 03 The Coalition: Voters, Parties and Institutions Introduction The formation of the Conservative-Liberal In his opening paper, Bob Worcester discusses Democratic administration in May 2010 was a public opinion and support for the parties in major political event. -

Conduct of Mr Dominic Cummings

House of Commons Committee of Privileges Conduct of Mr Dominic Cummings First Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 March 2019 EMBARGOED ADVANCE NOTICE: Not to be published in full, or in part, EMBARGOED ADVANCE NOTICE: Not to be published in full, or in part, in any form before 11.00am on Wednesday 27 March 2019 in any form before 11.00am on Wednesday 27 March 2019 HC 1490 Published on 27 March 2019 by authority of the House of Commons Committee of Privileges The Committee of Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to consider specific matters relating to privileges referred to it by the House. Current membership Kate Green MP (Labour, Stretford and Urmston) (Chair) Sir Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Stewart Malcolm McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow South) Bridget Phillipson MP (Labour, Houghton and Sunderland South) John Stevenson MP (Conservative, Carlisle) Sir Gary Streeter MP (Conservative, South West Devon) Liz Twist MP (Labour, Blaydon) Powers The constitution and powers of the Committee are set out in Standing Order No.148A. In particular, the Committee has power to order the attendance of any Member of Parliament before the Committee and to require that specific documents or records in the possession of a Member relating to its inquiries be laid before the Committee. The Committee has power to refuse to allow its public proceedings to be broadcast. The Law Officers, if they are Members of Parliament, may attend and take part in the Committee’s proceedings, but may not vote. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 663 8 July 2019 No. 326 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 8 July 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Penny Mordaunt, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

View Daily Order Paper PDF File 0.03 MB

Tuesday 22 June 2021 Order Paper No.20: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Treasury 12.30pm Urgent Questions, including on: Results of the Events Research Programme (Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) Afterwards Ministerial Statements (if any) Until 7.00pm Northern Ireland (Ministers, Elections and Petitions of Concern) Bill: Second Reading Followed by Motions without separate debate: Programme No debate Statutory Instruments (Motions for approval) Until 7.30pm or for Adjournment Debate: Proposed closure of McVitie’s Tollcross half an hour factory (David Linden) WESTMINSTER HALL 9.25am Effect of the covid-19 pandemic on religious and ethnic minority communities throughout the world 11.00am Recovery of businesses in central London from the covid-19 outbreak 2.30pm Future of the Welsh rural economy 4.05pm Situation of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon 4.50pm Proposal for Wildbelt designation in planning system reforms 2 Tuesday 22 June 2021 OP No.20: Part 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 3 Chamber 6 Westminster Hall 8 Written Statements 9 Committees Meeting Today 13 Committee Reports Published Today 14 Announcements 18 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 20 A. Calendar of Business 42 B. Remaining Orders and Notices Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest. Tuesday 22 June 2021 OP No.20: Part 1 BUSINESS TOday: CHAMBER 3 BUSINESS TODAY: CHAMBER Virtual participation in proceedings will commence after Prayers. 11.30am Prayers Followed by QUESTIONS 1. Treasury The call list for Members participating is available on the House of Commons business papers pages. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

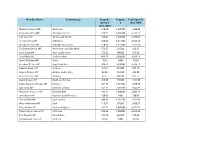

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

Open PDF 206KB

Procedure Committee Oral evidence: Procedure under coronavirus restrictions, HC 300 Monday 1 February 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 1 February 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Karen Bradley (Chair); Aaron Bell; Kirsty Blackman; Jack Brereton; Bambos Charalambous; Sir Christopher Chope; James Gray; Nigel Mills; Douglas Ross; James Sunderland; Owen Thompson; Liz Twist; Suzanne Webb; Mr William Wragg. Questions 457-514 Witness I: Rt Hon Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg MP, Leader of the House of Commons. Written evidence from witness: – HM Government (CVR 90) Examination of witness Witness: Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg MP. Chair: I welcome our witness, the Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons, the right hon. Jacob Rees-Mogg MP—my right hon. Friend. Thank you very much for appearing in front of the Committee today—virtually, once again, I am afraid. We will have plenty of questions for you about that issue and others as we go through the course of the day. As you will know, the Committee is not just looking at the way the House is operating under coronavirus. We have started an inquiry into the operation of the territorial system of the United Kingdom and the way in which the four legislatures operate together. I suspect there will be lots of questions about coronavirus, but to ensure that we can cover all those points, we would like to kick off with questions about that inquiry. We will then move on to the sifting Committee—the European Statutory Instruments Committee—and then to questions around coronavirus. -

…The New Working Dress Code

Volume 37 Number 1 Energy Data Taskforce report – Laura Sandys CBE The Impact of Net Zero on Energy Infrastructure – Sir John Armitt April 2020 New Shadow Cabinet Extract from the Budget Speech ENERGY FOCUS …the new working dress code This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Parliamentary Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in Energy Focus are those of the individual organisations and contributors and doBack not necessarily to Contents represent the views held by the All-Party Parlia- mentary Group for Energy Studies. The journal of The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Energy Studies Established in 1980, the Parliamentary Group for Energy Studies remains the only All-Party Parliamentary Group representing the entire energy industry. PGES aims to advise the Government of the day of the energy issues of the day. The Group’s membership is comprised of over 100 parliamentarians, 100 associate bodies from the private, public and charity sectors and a range of individual members. Published three times a year, Energy Focus records the Group’s activities, tracks key energy and environmental developments through parliament, presents articles from leading industry contributors and provides insight into the views and interests of both parliamentarians and officials. PGES, Room 2.2, Speaker’s House, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA www.pges.org.uk Executive