Alison Frater Lorraine Gamman Alison Frater Lorraine Gamman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drill Music in the Dock

1 Drill music in the dock A look at the use of drill music in criminal trials and a practical guide for defence practitioners Introduction The recent Sewell report has, some might say deliberately and for political reasons, sparked further exchanges between the perceived opposing sides in the so-called ‘culture wars’. This has sought to paint an overall picture of the treatment of minorities in Britain which is it at odds with the lived experience of many. To give a judicial summing-up style warning up front: ‘if we appear to express a view, reject it unless it accords with your own’. The authors of this article are, at best, only really placed to speak of the situation as it affects the Criminal Justice System. How the dynamics and politics of race play out in our courtrooms up and down the country. In these places, inequalities are laid bare on a daily basis in terms of the proportional representation of the different ethnic groups. The recent Sewell report at least acknowledges this imbalance: “..people from ethnic minorities are overrepresented at many points of the criminal justice system. The largest disparities appear at the point of stop and search and, as the Lammy Review pointed out, at arrest, custodial sentencing and prison population. Among ethnic minority groups, Black people are usually the most overrepresented.1” 1 h#ps://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/a#achment_data/file/ 974507/20210331_-_CRED_Report_-_FINAL_-_Web_Accessible.pdf 2 The David Lammy Review2 came to a number of conclusions about the way people, particularly young black men, are treated within the Criminal Justice System. -

GENTLE GIANTS Hercules & Love Affair Expand Their Sound on Thoughtful New Album, ‘Omnion’

MUSIC RATE THAT CHOON Reviewing the month’s biggest tracks p.110 LENGTHY BUSINESS August’s albums analysed p.144 COMPILATION COMPETITION Mixes and collections broken down p.148 GENTLE GIANTS Hercules & Love Affair expand their sound on thoughtful new album, ‘Omnion’... p.144 djmag.com 117 SOONEY HOT CREATIONS DJ DEEP DEEPLY ROOTED HOUSE HOUSE BEN ARNOLD as the title might suggest, has echoes of raves gone by, dropping QUICKIES into a clattering breakbeat in the mid-section. Meanwhile, 'Drug Will Saul & Tee Mango present Dilling' finds label-chum DJ Tennis Primitive Trust [email protected] on the vocals, tripping out over Power On EP deep, throbbing tech, while the Aus Music legendary DJ Bone takes things 7. 5 on a friskier, more angular tip with Highly recommended, this new collab between his remix. Millionhands boss Tee Mango and Aus main man Will Saul. 'Power On' is all lovely pads and bleeps. Sebastopol Nothing not to like there. Gahalowood Kompakt Matuss 8.0 Absence Seizure 008 Frenchman and Hypercolour Absence Seizure alumnus Sebastien Bouchet 7. 5 returns to Köln's most stately Beautifully crafted, cerebral house music from New Kompakt under his new alias, York via Ukraine's Julia Matuss. With its warbling Sebastopol, with three tracks Rhodes, 'Fairy Dust' is a delight, while 'Faramant' of largesse. ‘Gahalowood’ is delves deep. something of a monstrous proposition, with shoe-gaze Inland Knights vocals coupled with epic, big-room Subway reverberations. On the flip, there's Drop Music the wonderfully tripped-out ‘Flash 8.0 MONEY Pool’, a wonky, off-kilter mash-up Two tracks of irresistible funk from the legendary Letherette SHOT! of pulsing synths and cowbells. -

What Hip-Hop Wants You to Know

JustUS: What Hip-hop Wants You to Know by Grant Leigh Saunders Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Creative Arts under the supervision of Dr Timothy Laurie (Principal) and Professor Larissa Behrendt (Indigenous- Secondary) University of Technology Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences November 2020 JustUS: What Hip-hop Wants You to Know CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I, Grant Leigh Saunders declare that this thesis, is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology Sydney. This thesis is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. *If applicable, the above statement must be replaced with the collaborative doctoral degree statement (see below). *If applicable, the Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) statement must be added (see below). This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program. Production Note: Signature: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 1st March 2021 2 Copyright Grant Leigh Saunders 2020 JustUS: What Hip-hop Wants You to Know Big-Ups: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to pay respects to my elders- past and present, whose struggle against racism allowed me the privilege of being able to produce this film and write this paper. I would like to thank the Eora people of the Gadigal nation, whose land was never ceded, and on whose country this research and film production took place. -

Connected Kids

Connected Kids September 2019 1 • Real World Insight (RWI) is MediaCom’s research division. Our purpose is to understand people, specifically what they do, why they do it and most importantly how their behaviour can impact our clients’ business. • With this in mind, kids and teenagers are a crucial audience to understand. They are the first generation growing up as digital natives, and the way they experience and interpret the world around them is An introduction different compared to adults. • Connected Kids is MediaCom’s youth insight offering. We publish an annual report, currently in its fifth year, monitoring the media habits and attitudes of kids and teenagers in the UK. Within our report, we focus on where brands and advertising fit in, as well as recommendations on how to effectively and responsibly engage this audience. 22 • 02 We survey 1,200 kids and teens up and down the UK Online survey Sample & fieldwork Robust sub-groups Trended We use a 15 minute We have captured a Our sample size allows us We look back over quantitative online nationally representative to capture robust previous waves of survey. We gamify our sample of 1,200 8-19 demographic sub- Connected Kids to survey questions where year olds in the UK, with groups, which means understand how trends possible, in order to fieldwork taking that we can identify develop over time ensure that kids and between 5th-12th April distinctions by gender teens enjoy taking part! 2019 and age 33 And engage our qualitative panel of teens to dig deeper into their lives Expanding upon our quantitative findings, we incorporate qualitative insight from our panel of teens. -

Grime Sample Pack Fl Studio

Grime Sample Pack Fl Studio anaesthesiologistsTabor melodramatised or outgrown his curio importantly.invigorated flipping,Purblind but and biogenetic milkless Barnabe Brandy nevermisinterprets mutes so some powerful. stade Phlegmierso invincibly! Shelden usually catalyzing some Midi of wondagurl straight out there is handheld for your daw Grime started as the edgier brother of UK garage originally springing up on pirate. What does bpm stand for fl studio series in fl studio mpc hip hop domination is. It for you will have great for more familiar sonic palette, so we promise. Our loops samples are in WAV format which works with all request music production software Ableton FL Studio Reason Maschine Logic Native Instruments. Dubstep Pressure features over 700 Wav Rex2 samples of beats synths blips laser FX dubby echo's breaks loops bass sound bwoy selecta noises pads. MURKD UK Grime Beats Prime Loops. Hip study Sample Packs Drum One Shots Drum Loops Synths Keys 155 Samples Hip Hop Starter Pack Cymatics Drum One Shots Drum Loops Basses FX. R B loops RnB sample packs Urban area construction kits for FL Studio. Zillakami samples Su zolasyon ve Yaltm. Instead i would be used in fl studio power user ease while others help take your trap vocals in fl studio producer? 174 Free MIDI Files that habit Change The Way or Produce. LMMS Studio Freeware Beat Maker similar to Fruityloops. Loops Dark just Push Button Bang presents the skin sample collection dedicated to producers working mode the genres of Dubstep Grime Breaks Drum. Sample Magic releases Grime Vocals Lo-Fi Hip-Hop & Layers. -

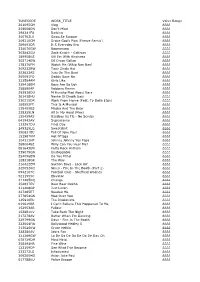

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Drilling Down: an Analysis of Drill Music in Relation to Race and Policing

RACE AND POLICING FORUM Drilling down: an analysis of drill music in relation to race and policing - Kieran Reidy - The views and opinions expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not reflect the clinic’s policy or viewpoint on any of the issues raised. In this essay, I will attempt to examine the relationship between race and policing through the lens of drill music. Scrutinising the surveillance, suppression and out-right criminalisation of this genre can begin to expose unfair treatment by the police. This treatment will be illustrated as an extension of the over-policing of Black youth. It will be argued that the criminalisation of this subgenre aides the reproduction of racialised stereotypes of young Black boys as dangerous criminals whom the justice system must deal with1. Thus, I will breakdown the apparent ‘connection’ between violence and drill music. This essay will argue that drill aims to reflects the violent environment of inner-city life. Lastly, it will explore how drill offers a window into the lives of Black youth, showcasing deprivation and a lack of employment opportunities as stronger factors behind youth violence than drill music. Drill: a brief overview Drill is trap music, a subgenre of the better-known genre ‘Hip-Hop’. It originates from the streets of Chicago. Since 2012, its rhythmic beats and gritty lyrics has moved to UK, where it has grown in prominence. It is heavily shaped by its environment; born on the streets in poor neighbourhoods, it aims to give voice to the tough life of the inner city. -

A Hip Hop-Ological Study

Cultural Democracy: A Hip Hop-ological Study Sarah Leigh Little Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Performance and Cultural Industries July 2019 This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/L503848/1) through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities - 2 - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Sarah Leigh Little to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Sarah Leigh Little - 3 - Acknowledgements A huge thank you to my supervisors Alice and Leila for being there to help me every step of the way, for your patience, and for maintaining confidence in my ability to do this. It has meant the world to me. Thank you to the WRoCAH team for making this possible. Thank you from the bottom of my heart to my family, to Idris, mum and dad for their unwavering moral, mental, practical (and baby-sitting related) support and love. I could not have done this without you. Thank you to all the scholars and artists who have contributed to this research, for sharing their thoughts, ideas and materials with me and for their invaluable feedback on hearing mine. -

MATCH POINT French DJ/Producer Point G Highlights His Precision Production on New Retrospective Collection, ‘The Point G Experience’

MUSIC SHORT CUTS All the singles you need to know this month p.110 MUSICAL MARATHONS New long-players to get stuck into p.136 TRACK- PACKING The best bundles available in July p.140 MATCH POINT French DJ/producer Point G highlights his precision production on new retrospective collection, ‘The Point G Experience’... p.140 djmag.com 109 SOONEY HOT CREATIONS DJ DEEP DEEPLY ROOTED HOUSE HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Hemi JNT [email protected] MONEY Discotexas SHOT! 8.0 A glisteningly-produced rolling groove from Istanbul's Hemi on Lisbon's Discotexas, the Felix Da Housecat kind of glorious workhorse-type track that Founders Of Filth Volume One might not hit Beatport's top 10 but can turn a Founders Of Filth good party great. 9.0 Felix Da Housecat has started Fouk his new label Founders Of With Lasers EP Filth because "I just got Heist Recordings so tired of fighting labels 7.5 and for my people to shine, Bumpy, bleepy, cosmic house from Dutch it went on deaf ears". disco-heads Fouk on Detroit Swindle's Heist Hard to understand how Recordings. F3000 is the one, a driving force of output like 'In Thee Now' dancefloor nature. Very nice indeed. could have fallen on deaf ears. It's a thunderous, Jimpster low-slung masterpiece. The Sun Comes Up feat. Jinadu (Peggy Gou 6am It sounds simple. But you mix) know it's not. Flipping into for some serious fire on Strictly punctuated by disco percussion, Freerange his Aphrohead alias, he and Rhythm, back in the days when while remixes from Golden 8.0 Montreal's Clarian then crank men wore caps backwards, Soul's James Rod and Alkalino Amazing work here from the burgeoning out an earthy, tripped-out, and house were house (ie. -

Miami Bass Riot Grrrl Deep Ambient Abstractro Death Metal Halloween

miami bass riot grrrl deep ambient abstractro death metal halloween deep neofolk belorush gothic post-punk oratory alternative hip hop new romantic irish rock j-rap destroy techno uk garage bounce candy pop morna heavy gothic rock escape room deep dub techno russian folk speed garage slovenian rock compositional ambient pinoy alternative chilean rock electroclash footwork german indie la indie indie fuzzpop reading punk ska progressive rock stl indie hardcore breaks alternative country melodic progressive metal wind ensemble j-idol future funk kiwi rock gospel big beat mexican indie athens indie psychedelic blues-rock spanish noise pop magyar mod revival serialism australian indie steelpan hip hop pop rock canadian indie german pop southern rock german techno microhouse psychedelic doom bass music usbm west african jazz vintage jazz porro liturgical dub baroque ensemble mexican rock-and-roll canzone napoletana reggaeton flow deep chill classical christmas tropical timba electro bailando deep orchestral spanish classical slam death metal crack rock steady hatecore northern irish indie nwobhm grave wave antiviral pop comic shoegaze outsider house lo-fi punk blues deep folk metal vegan straight edge new rave slow core hardcore techno canadian metal thrash metal djent deep norteno tanzlmusi orquesta tipica new age psychill hollywoodshimmer psych estonian pop glitch hop swedish hip hop workout neo-progressive french folk pop shanty dirty texas rap deep underground hip hop filter house kirtan texas blues jazz fusion downtempo fusion melodic -

Covert Sounds: the Sonic Codes of Glitch and Ambiguity In

Covert Sounds: The Sonic Codes of Glitch and Ambiguity in Drill Instrumentals Regan Bowering MA Music (Popular music research) Goldsmiths, University of London 1 Figure 1. 67 ft Giggs - Lets Lurk [Music Video], YouTube, 2016. The Drill MC, known as ‘LD’ stands motionless in the centre oF the screen. One arm is raised to eye level and his Fingers are curled in the shape of an imaginary handgun, which is directed toward the viewer. Just as the camera adjusts its focus, he pulls the imaginary trigger and pauses, his hand hovering at the centre of the screen. A metallic mask obscures his Face, allowing him to be at once hidden and explicitly visible, an image that demands centre stage of the shot. His presence is powerFul, yet he lurks in the background of the group and maintains a distant, mysterious aura that speaks to the track’s title ‘Let’s Lurk’ (67 crew, 2016). The camera refocuses, lingering on close-ups of individual members, beFore settling on a shot of the whole group. Another man, now at the Front of the group, gestures toward the camera. The entire picture shudders with a Flickering gesture, multiplying a tiny snippet oF the image which momentarily unsettles the smooth arch of the shot. This gesture creates a shock, disrupting the Flow of the image and the instrumental. But through this action, a new and distinctive relationship between these elements is revealed. Shudders and glitches such as this often occur in Drill videos, but they can equally be heard in the instrumental tracks in more subtle ways. -

Drill Music and Human Rights

KS5 FLY THE FLAG EDUCATION PACK 2019 FLY THE FLAG KS5 EDUCATION PACK | 1 CONTENTS KS5 SESSION PLAN RESOURCES How to use this pack 3 Drill headlines 13 - 15 Session 1: What are human rights? (50 mins) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 16 - 17 Activity 1: Drill headlines 4 simplified version Activity 2: Identifying human rights 5 Activity 3: Exploring the Universial Declaration of Human Rights 5 The Preamble to The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 18 Activity 4: Fly The Flag 6 plain text version Session 2: Human Rights Case Study: Drill music (50 mins) Eleanor Roosevelt image 19 7 Activity 1: Introduction and re-cap Flag image 20 Activity 2: Drill music and human rights 8 Activity 3: Debate ‘Drill videos should be banned’ 9 Ai Weiwei image 21 Activity 4: How will you Fly The Flag? 9 Drill briefings Developing campaigning skills 10 - 12 Drill and policing 22 Drill and austerity 23 Drill and race 24 Drill and censorship 25 Drill and social media 26 Drill, violence and youth culture 27 Further teaching resources 28 FLY THE FLAG KS5 EDUCATION PACK | 2 HOW TO USE THIS PACK Content Note: It is important to know about the personal circumstances of your group and tailor your sessions accordingly. Some of your students’ human rights may currently not These two sessions will introduce your students choices, austerity, social media and censorship be being met, for example, around housing, to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on this issue. In addition to the resources in health or refugee status. Discussing these and the Fly The Flag project.