Liner Notes by Michelle Mercer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In-Demand Drummer Rudy Royston Steps out As a Leader with 303

Two for the Show Media Chris DiGirolamo PO Box 534 Mattituck, New York 11952 tel: 631-298-7823 cell: 718-669-0752 www.Twofortheshowmedia.com Email: [email protected] _________________________________________ th For Immediate Release: Release Date: February 4 , 2013 Greenleaf Records In-Demand Drummer Rudy Royston Steps Out as a Leader with 303. Greenleaf Music debut scheduled for February 4th, 2014 release features ten Royston originals plus interpretations of Mozart and Radiohead. Since moving to New York City in 2006 from his home base in Denver, Rudy Royston has emerged as one of the most exciting and in- demand young drummers on the jazz scene. Having already racked up a list of impressive credits as a sideman with the likes of rising star of the tenor sax, J.D. Allen, alto saxophonist Tia Fuller, bassist Ben Allison, guitarist Bill Frisell and trumpeter Dave Douglas, Royston was ready to step out as a leader in his own right. His debut on Greenleaf Music, 303 (named for Denver’s area code), not only features his brilliant and versatile playing on the kit but also showcases his considerable skills as a composer on ten originals. With a stellar crew of some of the brightest young lights on the New York scene -- guitarist Nir Felder, pianist Sam Harris, saxophonist Jon Irabagon, trumpeter Nadja Noordhuis and the two-bass tandem of Mimi Jones and Yasushi Nakamura -- Royston and company also turn in dramatic interpretations of Mozart’s “Ave Verum Corpus” and Radiohead’s “High and Dry” on this outstanding debut. “Rudy is such a dynamic drummer, intensely polyrhythmic, both subtle and explosive,” says trumpeter-composer-bandleader and Greenleaf Music founder Dave Douglas. -

Myra Melford & Snowy Egret Language of Dreams

Saturday, November 19, 2016, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Myra Melford & Snowy Egret Language of Dreams Conceived and composed by Myra Melford Myra Melford’s Snowy Egret Myra Melford, piano, melodica, and sampler Ron Miles, cornet Liberty Ellman, guitar Stomu Takeishi, acoustic bass guitar Tyshawn Sorey, drums David Szlasa, video artist and lighting design Oguri, dancer and choreography Sofia Rei, narrator/spoken text Hans Wendl, artistic direction and production Texts excerpted from Eduardo Galeano’s Memory of Fire (Memoria del Fuego ) trilogy: Genesis (1982) Faces and Masks (1984) Century of the Wind (1986) Copyright 1982, 1984, 1986 respectively by Eduardo Galeano. Translation copyright 1985, 1987, 1988 by Cedric Belfrage. Published in Spanish by Siglo XXI Editores, México, and in English by Nation Books. By permission of Susan Bergholz Literary Services, New York, NY and Lamy, NM. All rights reserved. e creation and presentation of Language of Dreams was made possible by Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award, and a University of California Faculty Research Grant. Jazz residency and education activities generously underwritten by the Thatcher-Meyerson Family. n e s i o B s e l y M Myra Melford (far right) with Snowy Egret Language of Dreams I Prelude e Promised Land Snow e Kitchen II e Virgin of Guadalupe A Musical Evening For Love of Fruit/Ching Ching III Language IV Times of Sleep and Fate Little Pockets/Everybody Pays Taxes Market e First Protest V Night of Sorrow Day of the Dead e Strawberry VI Reprise – e Virgin of Guadalupe This performance will last approximately 75 minutes and will be performed without intermission. -

Jazz Trio Plays Spanos Theatre Oct. 4

Cal Poly Arts Season Launches with Jazz Trio Oct. 4 http://www.calpolynews.calpoly.edu/news_releases/2006/September... Skip to Content Search Cal Poly News News California Polytechnic State University Sept. 11, 2006 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jazz Trio Plays Spanos Theatre Oct. 4 SAN LUIS OBISPO – In a spectacular showcase featuring jazz greats Bill Frisell (guitar/banjo), Jack DeJohnette (drums, percussion, piano) and Jerome Harris (electric bass/vocals), Cal Poly Arts launches its new 2006-07 performing arts season. The trio of master musicians will perform on Wednesday, October 4, 2006 at 8 p.m. in the Spanos Theatre. The evening will include highlights from the acclaimed release, “The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers.” Recorded at Seattle’s Earshot Festival in October 2001, “The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers” brilliantly captures the collaboration of two unparalleled musical visionaries: Jack DeJohnette -- “our era’s most expansive percussive talent” (Jazz Times) -- and Bill Frisell, “the most important jazz guitarist of the last quarter of the 20th century” (Acoustic Guitar). DeJohnette and Frisell first worked together in 1999. “We immediately had a rapport and we talked about doing more,” DeJohnette recalls. Frisell needed no convincing: “I have been such a fan of Jack’s since the late ’60s when I first heard him,” the guitarist says. “He’s been such an influence and inspiration throughout my musical life.” The two got together the afternoon before the 2001 Earshot concert and at the soundcheck, ran through a couple of numbers, but the encounter was largely improvised. “We had a few themes prepared,” Frisell says, “but it was pretty much just start playing, and go for it.” According to DeJohnette, “Bill and I co-composed in real time, on the spot” for “The Elephant Sleeps...” The album features 11 tracks covering a breadth of sonic territories. -

Sarà Il Chitarrista Bill Frisell, Ad Aprire Venerdì 9 Novembre, Ore 21, Alla Fiera Di Cagliari, Una Delle Notti Jazz Che Si P

36° Festival Internazionale Jazz in Sardegna – European Jazz Expo BILL FRISELL (solo) ENRICO RAVA 5et feat. JOE LOVANO Centro Congressi della Fiera di Cagliari, venerdì 9 novembre (ore 21) Sarà il chitarrista Bill Frisell, ad aprire venerdì 9 novembre, ore 21, alla Fiera di Cagliari, una delle notti jazz che si preannuncia esplosiva per il valore e la fama degli artisti che si esibiranno sul palco. Un unico concerto che vedrà, dopo l’esibizione di Frisell in solo, anche il live di un quintetto d’eccezione, il supergruppo formato dal sassofonista Joe Lovano, il trombettista Enrico Rava il contrabbassista Dezron Douglas, il batterista Gerald Ceaver e il pianista Giovanni Guidi. Bill Frisell, stella indiscussa del panorama musicale mondiale, riconosciuto non solo come uno dei chitarristi più inventivi di sempre ma anche come uno dei più versatili e prolifici, si esibirà in solo sul palco della fiera nella prima parte della serata. Con una carriera trentennale e oltre cento dischi pubblicati alle spalle, Frisell è tra le figure più di spicco nell’ambito jazzistico, con un repertorio che sconfina spesso nei territori del folk, del country, del pop e della musica d’avanguardia. Ha collaborato tra gli altri con Paul Motian, John Zorn, Elvis Costello, Marianne Faithfull, John Scofield, Jan Garbarek, Paul Bley, Bono, Robin Sylvian. Alcuni critici lo hanno paragonato a Miles Davis per il suo stile caratterizzato dalla ricerca del puro suono e dall’antitecnica inconfondibile. I suoi dischi coprono un ampio raggio di generi e influenze musicali: dalle colonne sonore di film di Buster Keaton e dei cartoni animati di Gary Larson (Quartet) alle composizioni originali per grossi ensemble con archi e collaborazioni con il bassista Viktor Krauss e il batterista Jim Keltner. -

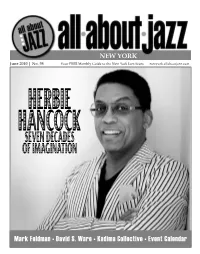

June 2010 Issue

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

SFJAZZ Announces 2021-2022 Season Programming September 23, 2021 – May 29, 2022

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SFJAZZ Announces 2021-2022 Season Programming September 23, 2021 – May 29, 2022 Tickets on Sale to SFJAZZ Members, Thursday, July 29 at 11:00amPST Tickets on Sale to Public, Thursday, August 5 at 11:00amPST SFJAZZ.ORG (SAN FRANCISCO, CA, July 22, 2021) -- SFJAZZ announces the 2021-2022 Concert Ceason running September 23, 2021 to May 29, 2022. The organization will be presenting concerts at the SFJAZZ Center’s Robert N. Miner Auditorium and Joe Henderson Lab, Grace Cathedral, and Paramount Theatre in Oakland. Tickets will go on sale to SFJAZZ Members on Thursday, July 29 at 11:00am PST and on sale to the general public on Thursday, August 5 at 11:00amPST. For more information, visit sfjazz.org. SFJAZZ will celebrate the official Re-Opening of the SFJAZZ Center with its first full-capacity concert since March 2020 on Thursday, September 23 featuring Thelonious Monk Competition winner and soundtrack composer for Bridgerton and Green Book, pianist Kris Bowers. The SFJAZZ Center Re-Opening weekend includes concerts featuring Zakir Hussain, Eric Harland, and Abbos Kosimov on Friday September 24, and Pat Metheny’s Side-Eye project with James Francies and Joe Dyson on Saturday, September 25 and Sunday, September 26. “Over the past 18 months, all of us have been torn from the rhythms of everyday life and with the SFJAZZ 2021-2022 Season, and what is the our 39th year, we – artists, staff, and board -- are looking forward to a new rhythm and welcoming audiences back to the SFJAZZ Center,” says SFJAZZ Founder and Executive Artistic Director Randall Kline. -

João Gilberto

SEPTEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Palo Colorado Dream Press Release

Bio information: ANTHONY PIROG Title: PALO COLORADO DREAM (Cuneiform Rune 398) Format: CD / DIGITAL DOWNLOAD Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / ROCK / EXPERIMENTAL Washington D.C.’s Leading Jazz/Experimental/Rock Guitarist, Anthony Pirog, Goes National with Palo Colorado Dream, His Debut Album as a Trio Leader with Acclaimed Drummer Ches Smith and Bassist Michael Formanek Washington, D.C.’s thriving jazz and experimental music scenes wouldn’t be quite where they are today without Anthony Pirog. The guitarist, composer and loops magician is a quiet but ubiquitous force on stages around his hometown. With fearsome chops and a keen ear for odd beauty, Pirog has helped expand the possibilities of jazz, rock and experimentalism in a city formerly known for its straight-ahead tradition. Pirog performs regularly in a broad spectrum of venues (and musical contexts) across DC – jazz and rock clubs, the Kennedy Center Millenium Stage, art galleries and museums, the annual Sonic Circuits Festival of Experimental Music, and much more. DC has a rich legacy of brilliant guitarists and gifted composers – Danny Gatton, Roy Buchanan, John Fahey, and Duke Ellington come to mind for key roles they played in the city’s 20th Century musical past. In the cutting-edge cultural and technological mecca that is the new, 21st Century Washington, Anthony Pirog is DC’s leading guitarist/composer and fast rising star. Palo Colorado Dream—recorded with the all-star trio of Michael Formanek on bass and Ches Smith on drums—is Pirog’s Cuneiform Records debut as a bandleader, and it marks the young innovator’s entrance onto the national stage. -

Bill Frisell Interview by Ken Gallo of Meet the Composer Guitarist/Composer Bill Frisell Is Looking for That "Thing."

Bill Frisell interview by Ken Gallo of Meet The Composer Guitarist/Composer Bill Frisell is looking for that "thing." He always has been. The quest started in high school with the clarinet, brought him to NYC in 1979, and passed through Nashville, Tennessee in 1996. He hasn't found it yet, and he probably never will. Why should he? Searching for it has made Mr. Frisell's eclectic career what it is today. That "thing" is what he believes is at the core of art, the layers of subtext behind what we see and hear. Mr. Frisell, who cemented his reputation as the "downtown" New York City avant- jazz guitarist in the late 1980s (most notably with John Zorn's Naked City) would have seemed quite out of place in Nashville, Tennessee, but it was there that he recorded one of his biggest triumphs: the critically acclaimed Nashville. Although recorded with many local country/bluegrass musicians, the recording, as with most of his work, is of an unidentifiable genre, just like Mr. Frisell himself. More recently, Mr. Frisell recorded The Willies (2002); a trio record with jazz legends Dave Holland (bass) and Elvin Jones (drums), Bill Frisell with Dave Holland and Elvin Jones (2001); as a sideman on vocalist Norah Jones's Come Away With Me (2002); and scored music for films (including Wim Wenders' Million Dollar Hotel and Gus Van Zant's Finding Forrester). He was commissioned by Meet The Composer's Commissioning Music/USA 2002 for the multi-media suite Mysterio Sympatico, a collaboration with the "alternative" cartoonist/visual artist Jim Woodring (who has done the art work for the covers of Mr. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Joshua Redman: Still Dreaming

Joshua Redman: Still Dreaming Start time: 7.30pm Set times: 19.30pm Duncan Eagles Trio 8pm interval 8.20pm Joshua Redman All times are approximate and subject to change Kevin Le Gendre speaks to Joshua Redman about jazz, his creative process and his Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change father’s legacy ahead of his performance. ‘New bottle, old wine’ is a poetic image for a fundamental principle in jazz. It refers to the process of reinterpreting, reviving and rebooting songs of the past with the energy and ideas of the present. When saxophonist -composer Joshua Redman decided to perform the music of the legendary ensemble Old and New Dreams he was upholding this culture, but there was also a compellingly personal subtext to the project. The quartet, active between the late 70s and late 80s, was jointly led by his father, saxophonist Dewey, trumpeter Don Cherry, double bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell. All of the above played with Ornette Coleman, a visionary who ushered in daring new approaches to composition and improvisation. Redman, who actually played with Dewey, as well as Haden and other Coleman alumni, Billy Higgins and Pat Metheny, in the early 90s, was moved to launch his Old and New Dreams project four years ago following Haden’s death. ‘There was a memorial [for him] in January 2015 at Town Hall in New York that I was a part of,’ Redman explains. ‘I found myself, immediately after, listening to his music and a lot of music my father was a part of. -

Burt Bacharach

Late Night Jazz: Burt Bacharach Samstag, 10. August 2019, 22.05 - 24.00 Uhr Eine Wiederholung vom 13. August 2016 Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Andreas Müller-Crepon Carpenters: Singles 1969-1981 (1971) CD A&M Track 20: Close To You David Hazeltine: Close To You (2003) CD Criss Track 1: Close To You Bill Frisell: The Sweetest Punch (1998) CD Decca Track 15: God Give Me Strenght Track 1: The Sweetest Punch Track 6: What’s Her Name Today Track 10: I Still Have That Other Girl Metropol Orchestra / Traincha: The Look of Love (2006) CD Blue Note Track 6: I’ll Never Fall In Love Again Track 7: Falling Out of Love Diana Krall: Diana Krall In Paris (2002) CD Verve Track 4: The Look of Love Stan Getz: What the World Needs Now. Stan Getz plays Bacharach (1967) CD Verve Track 11: Walk On By Track 4: Any Old Time of the Day Elvis Costello: Painted From Memory (1998) CD Mercury Track 9: Painted From Memory Johnny Hartmann: Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head CD Definitive Track 11: Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head Don Byron: The New Songs of Elvis Costello and Burt Bacharach (1998) CD Decca Track 9: My Thief Track 3: Such Unlikely Lovers David Hazeltine: Modern Standards (2004) CD Sharp Nine Track 2: A House Is Not a Home Rigmor Gustafsson: Calling You (2010) CD ACT Track 4: I Just Don’t Know What To Do Russell Malone: Black Butterfly (1993) CD Columbia Track 6: I Say a Little Prayer For You Ani Di Franco : My Best Friend's Wedding CD Work Sony Track 2: Wishin’ and Hopin’ Larry Goldings Trio: Sweet Science (2002) CD Palmetto Track 5: This Guy’s