Advisory Visit River Mimram, Hertfordshire April 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Read, Simon ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2380-5130 (2017) Cinderella River: The evolving narrative of the River Lee. http://hydrocitizenship.com, London, pp. 1-163. [Book] Published version (with publisher’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23299/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Singlers Marsh Plan

SINGLERS MARSH LOCAL NATURE RESERVE WELWYN HERTFORDSHIRE Management Plan 2014 -2024 (JUNE 2014) SINGLERS MARSH, WELWYN, HERTFORDSHIRE Management Plan Section 1 DESCRIPTION 1 1.1 Name of Site 1 1.2 Location 1 1.3 Tenure 1 1.4 Legal Constraints 1 1.5 Physical Description 2 1.6 Ecological Description 2 1.7 Site History 5 1.8 Present Use 6 Section 2 EVALUATION 6 2.1 Wildlife Value 7 2.2. Amenity Value 7 2.3. Educational Value 7 2.4 Site Potential 7 2.5 The Role of Countryside Stewardship 8 Section 3 FUTURE MANAGEMENT 8 3.1 Objectives of Future Management 8 3.2 Management Proposals 8 3.3 Getting the work done 10 3.4 Community Involvement 10 Section 4 ANNUAL WORK PROGRAMME 11 Section 5 SITE MONITORING & REVIEW 12 5.1 Annual Monitoring 12 5.2 Plan Review 12 Section 6 Maps Section 1 DESCRIPTION 1.1 Name of Site Singlers Marsh Local Nature Reserve 1.2 Location Singlers Marsh is located to the immediate north of the village of Welwyn. A little more than three quarters of the site lies within the area administered by Welwyn Hatfield Council in central Hertfordshire, the remainder being within North Hertfordshire District Council’s area. The site’s eastern boundary is formed by the River Mimram and by enclosed private gardens along the B656 road between Welwyn and Codicote. On the west side are public roads with more residential properties. To the east of the site beyond the Codicote Road is Danesbury Local Nature Reserve, also owned by Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council. -

Appraising Chalk Streams Using Citizen Science

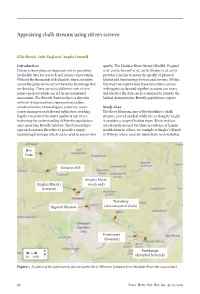

Appraising chalk streams using citizen science Ellie Beach, Judy England, Angela Gurnell Introduction quality. The Modular River Survey (ModRS; England Citizen science plays an important role in providing et al. 2017a, Gurnell et al., 2016, Shuker et al. 2017) invaluable data for research and nature conservation. provides a means to assess the quality of physical Without the thousands of dedicated citizen scientists habitat and functioning of rivers and streams. Within across the globe we would not have the knowledge that this study we explore how these two citizen science we do today. There are many different river citizen techniques can be used together to assess our rivers science projects which can aid in environmental and whether the data can be combined to identify the assessment. The Riverfly Partnership is a dynamic habitat characteristics Riverfly populations require. network of organisations, representing anglers, conservationists, entomologists, scientists, water Study sites course managers and relevant authorities, working The River Mimram, one of Hertfordshire’s chalk together to protect the water quality of our rivers; streams, proved an ideal study site as along its length furthering the understanding of Riverfly populations it provides a range of habitat types. Many sections and conserving Riverfly habitats. The Partnership’s are relatively natural but there is evidence of human approach assesses Riverflies to provide a simple modification in others, for example at Singler’s Marsh monitoring technique which can be used to assess river in Welwyn where concrete banks have been installed Hoo Farm Kimpton Mill Singlers Marsh Singlers Marsh 1 (south end) (restored) Tewinbury Digswell Meadow (downstream of drain) Panshanger (diversion) Panshanger (disturbed by bench) Figure 1. -

East Hertfordshire District Council Level 1 and 2 Strategic Flood Risk

ESSENTIAL REFERENCE PAPER B East Hertfordshire District Council Level 1 and 2 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Final Report August 2016 East Hertfordshire District Council P O Box 104 Wallfields, Pegs Lane HERTFORD SG13 8EQ This page is intentionally left blank 2016s4502 East Hertfordshire District Council - Level 1&2 SFRA Final v1.0 i JBA Project Manager Joanne Chillingworth JBA Consulting The Library St Philip’s Courtyard Church End COLESHILL B46 3AD Revision History Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to Draft v1.0 / August 2016 Chris Butcher, East Hertfordshire District Council Final v1.0 / August 2016 Chris Butcher, East Hertfordshire District Council Contract This report describes work commissioned by East Hertfordshire District Council. The Council’s representative for the contract was Chris Butcher. Prepared by .................................................. Alice Blanchard BSc Analyst Sophie Dusting BSc MEPS Analyst Reviewed by ................................................. Joanne Chillingworth BSc MSc MCIWEM C.WEM Chartered Senior Analyst Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for East Hertfordshire District Council. JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document other than by the Client for the purposes for which it was originally commissioned and prepared. JBA Consulting has no liability regarding the use of this report except to East Hertfordshire District Council. 2016s4502 East Hertfordshire District Council - Level 1&2 SFRA Final v1.0 ii -

Riverside Tales

Riverside tales Lessons for water management reform from three English rivers Riverside tales 1 Contents 1 Executive summary 3 Introduction 4 Unsustainable abstraction – the problem of taking too much 8 The iconic chalk stream – the Itchen 15 The Cinderella rivers – the Mimram and the Beane 23 Over the hill and far away – the upper Kennet 27 What can we learn? – barriers to reducing damaging abstraction 32 Moving forward – a new approach to restoring sustainable abstraction WWF is working on freshwater issues in the UK to: n Safeguard the natural world by protecting our native ecosystems n Change the way we live, so we waste less water n Tackle climate change by promoting water management measures that will help our rivers cope with a climate change. 2 Riverside tales Executive summary WWF’s Rivers on the Edge programme campaigns to raise n Plans for water efficiency fell short – annual water efficiency awareness of the impact on nature from taking too much plans expect to save the equivalent of just 0.34% of total water from our rivers. We’re working to develop solutions water supplied to households. A significant number of water to help reduce waste and protect our rivers now, and in company Water Resource Management Plans do not aim to the face of climate change. In 2009, a number of key plans meet the government’s target of 130 litres per person per day were finalised that will impact on how water is managed by 2030. for years to come: the 2009 Periodic Review of Water n Plans for tackling leakage stagnated. -

The Mill House

THE MILL HOUSE Tewin • welwyn • HerTfordsHire • Al6 0JQ A wonderful small country estate set on the river Mimram Welwyn North mainline station (Digswell) - Kings Cross from 29 minutes - 2.1 miles • Old Welwyn High Street 3.7 miles Welwyn Garden City - 2.8 miles • Knebworth (Kings Cross 33 mins) - 6.4 miles • Welwyn Garden City - 2.7 miles Stevenage - 9.4 miles • A1(m) junction 6 - 2.7 miles • London Luton Airport - 14.5 miles (All distances and times are approximate) The Mill House Reception hall • drawing room • family room • dining room • study • kitchen with larder • scullery • cloakroom • loggia master bedroom with balcony • 3 further bedrooms (1 with en suite shower room) • 2 further bath/shower rooms • EPC Rating = F The Wing Morning room • kitchen • 2 bedrooms • shower room The Bothy Sitting room • kitchen • utility/shower room • cloakroom • 2 bedrooms • EPC Rating = E North Lodge Entrance hall • sitting room • dining room • conservatory • kitchen • cloakroom • 2 bedrooms • shower room • EPC Rating = F Estate Grounds Beautiful river Mimram flowing through the garden• backwater • the border (mixed shrub and herbaceous) • summer house • arbour • woodland wonderful rose garden • wild flower meadows• donkey fields• orchard • extensive range of sheds and greenhouses • store room • garaging • carport • workshop In all – Approximately 9.83 acres (3.98 HA) Savills Harpenden Savills London 2 Station Road, Harpenden AL5 4SD 33 Margaret Street, London W1G 0JD Tel: 01582 465 002 Tel: 020 7016 3713 Contact: Nick Ingle Contact: Hugh Maconchie Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Mill House description Not seen in the open market for over 50 years, The Mill The Knight family embraced organic methods and kept House and its associated properties are now being weed killer to a minimum, so the gardens could thrive and offered for sale as a whole. -

Annual Monitoring Report 2010/11 December 2011

Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council Annual Monitoring Report 2010/11 December 2011 Part of the Local Development Framework LDF* www.welhat.gov.uk Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council Local Development Framework Annual Monitoring Report 2010/2011 Published December 2011 C.J. Conway Director of Strategy and Development Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council Council Offices The Campus Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL8 6AE Tel. 01707 357532 Fax. 01707 357285 Email: [email protected] If you would like to receive this document in a different language or format please call 01707 357000 or email [email protected] Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 5 Glossary ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 12 Progress of the Welwyn Hatfield Local Development Framework .......................................... 21 Statement of Community Involvement Monitoring ................................................................... 30 Monitoring and Implementation of District Plan Saved Policies ............................................. 34 The Environment ......................................................................................................................... 39 Safe, Healthy and Strong Communities -

Birchall Garden Suburb Green Infrastructure Strategy Part 1

BIRCHALL GARDEN SUBURB GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY October 2016 Birchall Garden Suburb Green Infrastructure Strategy Prepared for Tarmac Ltd by David Jarvis Associates Limited, 1 Tennyson Street, Swindon, SN1 5DT October 2016 Updated December 2016 Maps within this report are based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the controller of Her Majesty’s Sta onary Offi ce ©Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduc on infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecu on or civil proceedings. Reproduced with the permission of the controller of HMSO Licence No: AR189685 October 2016 2 Birchall Garden Suburb Green Infrastructure Strategy INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND This document has been prepared by David Jarvis Associates Ltd on behalf of A proposal for an extension to Welwyn Garden City, based on Ebenezer Howard’s Tarmac Trading Ltd. Tarmac is a long-term landowner and steward in Her ordshire Garden City principles, was prepared by David Lock Associates in 2007. The and has been promo ng a sustainable extension to Welwyn Garden City on land at resul ng Visioning Statement and illustra ve masterplan were supplied to WHBC Cole Green and Birchall Farm since 2006. and EHDC to inform their Local Plans. Scope The emerging masterplan has been the subject of a number of public consulta on This report describes the Green Infrastructure (GI) strategy for Birchall Garden events hosted by the Company. These included a Community Planning Weekend Suburb (BGS), a proposed urban extension to Welwyn Garden City, Her ordshire. It held in November 2015 and a public exhibi on in March 2016. The BGS site has includes a descrip on of the exis ng green and blue assets within the BGS site and also been the subject of a wide range of intensive environmental surveys over how they connect to the adjoining urban areas as well as the wider countryside. -

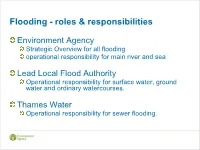

Flooding - Roles & Responsibilities

Flooding - roles & responsibilities Environment Agency Strategic Overview for all flooding operational responsibility for main river and sea Lead Local Flood Authority Operational responsibility for surface water, ground water and ordinary watercourses. Thames Water Operational responsibility for sewer flooding. The Strategic overview A strategic overview across all flooding risks to facilitate management through a risk based approach Strategic flood Local flood risk risk • Surface runoff • Main rivers • Groundwater • Sea • Ordinary • Reservoirs watercourses Coastal erosion Strategic overview Assets – maintenance, inspection and new schemes to reduce the risk EA FRM projects in Hertfordshire Furneux Pelham Stevenage Central Watford Improvement Works Hemel Hempstead London Colney Harpenden/Batford Puckeridge Little Hadham Cheshunt Stanstead Abbotts EA maintenance projects Aberford Road Oil Interceptor H&S Improvements Amwell Bailey Bridge, Ware - Refurbishment Aston Valley Flood Storage Area, Stevenage - Statutory Remedial Works Fieldes Weir, Hoddesdon - PLC Upgrade/Simplification Hardmead Sluice, Ware - Replacement of Flood Control Structure Hardmead Sluice, Ware - Replacement of Penstocks to Sluice Gate Heavy River Improvement Package LFRC Control Structures, Ware to Enfield Island - Gantry Hoist Replacement Package Meadgate Sluices, Hoddesdon, Actuator and Gearbox Replacement Papermill Stream Penstock, Channel and Bridge, Standon - M&E Upgrade & stuctural repairs Region wide Radio Frequency Tagging Identification of M & E Assets Sele Mill Siphon, Hertford - Electrical panel and lighting refurbishment Stanstead Radial Gate replacement located along the River Lee in Stanstead Abbott Warrengate Rd Flood Gate Repairs & Traffic Management Improvement EA environment projects Restoring passage on the River Beane up to Sele Mill Stort Valley Landscape Opportunity Area, River Stort. Little Hallingbury Marsh, Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), River Stort. -

River Mimram Aquatic Survey

Institute of Freshwater 0 Ecology Al(M) Widening Junctions 6 to 8 - River Mimram Aquatic Survey F.H. Dawson, PhD, MIWEM, CI3101,FIBiol M. Ladle, PhD S.M. Smith III WE IF ilaTtTJ Lonpit - Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF FRESHWATER ECOLOGY River Laboratory, East Stoke, Wareham, Dorset BH20 GBB Tel: 0929 462314 Fax: 0929 462180 Al(M) Widening Junctions 6 to 8 - River Mimram Aquatic Survey F.H. Dawson PhD, MIWEM, CBiol, FIBiol M. Ladle PhD S.M. Smith Project leader: F.H. Dawson Report date: September 1993 Report to: Catherine J. Bickmore Travers Morgan Environment Contract No: T11053n1 IFE Report Ref: RL/T11053n1/7 TFS Project No: RL/T11053n1 This is an unpublished report and should not be cited without permission, which should be sought through the Director of the Institute of Freshwater Ecology in the first instance. The Institute of Freshwater Ecology is part of the Terrestrial and Freshwater Sciences Directorate of the Natural Environment Research Council. CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION 1 RESULTS 2 CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 2 LIST OF FIGURES 4 Figure 1. Sketch map of R. Mimram at crossing with Al(M) at 6 Junction 6, Welwyn Figure 2. Sketch map of R. Mirnram at crossing with Al(M) at 7 Junction 6, Welwyn indicating community habitat types. Figure 3. Sketch map of R. Mimram at crossing with Al(M) at 8 Junction 6, Welwyn showing proposed alteration to river channel. APPENDICES Appendix 1 Field data survey sheets 9 2 Species lists - flora & fauna 19 3 Reconnaissance survey methodology 26 1. INTRODUCTION The River Mimram at Welwyn 1.01 The River Mimram. -

NRA Thames 263 UPPER LEE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL PLAN

NRA Thames 263 UPPER LEE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL PLAN f . 1 I w - % NRA National Rivers Authority Thames Region September 1994 CATCHMENT FACTS GENERAL WATER QUALITY Catchment area 486 sq km Length of watercourse (km) categorised by General Quality (82% in Herts, 18% in Beds) Assessment classes: 1991 - 1993 Highest point 210 m AOD River Lee Class B 28.0 (South of Dunstable) Class C 7.4 Class D 11.9 Lowest point 35 m AOD River Mimram Class A 10.3 (Hertford) Class B 12.8 River Beane Class C 12.2 Population 391 400 Stevenage Brook Class C 5.2 (48 % in Herts, 52 % in Beds) Pollution incidents in 1993 WATER QUANTITY Major 0 Significant 7 Annual average rainfall 639 mm Minor 100 Average flows in the River: Typical range of biological monitoring results in the River: Lee ( Waterhall) 108 Ml/d Mimram (Panshanger) 46 Ml/d BMWP ASPT Beane (Hartham) 52 Ml/d (Diversity) (Water Quality) Lee 15-181 Percentage of average flows derived from groundwater - 2.67-5.15 Mimram 3.84-5.16 surface water - sewage effluent in the River: 71 - 151 Beane 35-138 3.53-5.12 Lee 22% - 29% - 49% Mimram 79% - 18% - 3% Beane 60% - 40% - 0% FLOOD DEFENCE Length of main river’ (km) and areas of floodplain (ha) at risk Average abstraction of water from: of flooding according to land use types on the River: Chalk aquifers 98 Ml/d Length Area Other aquifers 3 Ml/d Lee Band B 11.8 117 Rivers 4 Ml/d Band C 10.3 61 Band D 13.5 Typical uses o f abstracted water: 123 Band E 28.4 60 Public water supply 88% Mimram Band C 5.2 28 Industrial 5% Band D 92 126 Gravel washing 2% Band E 9.2 41 Other 5% Beane Band C 8.2 155 Band D 17.8 239 Band E 52.9 140 Notes (1) 1 sq km (square kilometre) is equivalent to 0.36 square miles. -

Cinderella River © Simon Read 2017

Cinderella River © Simon Read 2017 Editor: Penny Rogers (SfEP) Publication commissioned by through the Arts & Humanities Research Council Connected Communities programme All images by Simon Read unless otherwise credited Printed by CDS (Corporate Document Services) Design and layout by U2R Design October 2017 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended) Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 2 Simon Read Simon Read is a visual artist and Associate Professor of Fine Art at Middlesex University London. As someone who has an intimate understanding of coastal dynamics, he has used his position as a senior academic to foster discussion on an interdisciplinary and international basis over the vital importance of understanding the cultural implications of environmental change. Aside from the study that generated this publication, he is actively engaged at a community level in Suffolk with estuary management schemes. Ongoing and recent research projects include CoastWEB, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and led by Plymouth Marine Laboratory, to use locations on the Welsh coast in a study of the community benefits of a healthy intertidal saltmarsh environment. His studio work has been exhibited widely both in the UK and abroad and is held in several major national and international collections. He has carried out several public commissions, including “A Profile of the River Thames, from Thames Head to Sea Reach” for the Thames Flood Barrier (1996) and “Memory and the Tideline” for the flood defence works on Poole Town Quay (2001).