And Lyrical Ballads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyrical Ballads

LYRICAL BALLADS Also available from Routledge: A SHORT HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE Second Edition Harry Blamires ELEVEN BRITISH POETS* An Anthology Edited by Michael Schmidt WILLIAM WORDSWORTH Selected Poetry and Prose Edited by Jennifer Breen SHELLEY Selected Poetry and Prose Edited by Alasdair Macrae * Not available from Routledge in the USA Lyrical Ballads WORDSWORTH AND COLERIDGE The text of the 1798 edition with the additional 1800 poems and the Prefaces edited with introduction, notes and appendices by R.L.BRETT and A.R.JONES LONDON and NEW YORK First published as a University Paperback 1968 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Second edition published 1991 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Introduction and Notes © 1963, 1991 R.L.Brett and A.R.Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Wordsworth, William 1770–1850 Lyrical ballads: the text of the 1978 edition with the additional 1800 poems and the prefaces. -

Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2015 Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800 Jason N. Goldsmith Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Jason N., "Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800" The Oxford Handbook of William Wordsworth / (2015): 204-220. Available at https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/876 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICAL BALLADS, 1800 205 [tha]n in studying German' (CL, r. 459). Stranded by the weather, short on cash, and C H A P TER 11 unable to communicate with the locals, the poet turned inward, writing a series of auto biographical blank verse fragments meditating on his childhood that would become part one of the 1799 Prelude, as well as nearly a dozen poems that would appear in the second volume of the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads. WORDSWORTH'S L YRICAL Completed over the eighteen months following his return to England in May 1799, the 1800 Lyrical Ballads is the fruit of that long winter abroad. It marks both a literal and BALLADS, 1800 a literary homecoming. Living in Germany made clear to Wordsworth that you do not ....................................................................................................... -

Sparrow Records Discography

Sparrow Discography by Mike Callahan, David Edwards & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Sparrow Records Discography Sparrow is a Contemporary Christian label founded in 1976 by Billy Ray Hearn. Hearn was the A&R Director for Word Records’ Myrrh label, founded a few years earlier also as a Contemporary Christian label. Sparrow also released records under their Birdwing subsidiary. Hearn’s Sparrow label was in competition with Hearn’s old boss, Word Records, and was quite successful. Even today, Sparrow is among the top Christian labels. Hearn sold the label to EMI in 1992, and it was placed under the Capitol Christian Music Group. Sparrow signed a distribution agreement with MCA in April, 1981 to release their product in the secular market while the regular Sparrow issues were distributed to Christian stores and Christian radio stations. The arrangement with MCA lasted until October, 1986, when Sparrow switched distribution to Capitol. Sparrow SPR-1001 Main Series: SPR-1001 - Through a Child’s Eyes - Annie Herring [1976] Learn A Curtsey/Where Is The Time/Wild Child/Death After Life/Grinding Stone/Hand On Me//Dance With You/Love Drops/Days Like These/First Love/Some Days/Liberty Bird/Fly Away Burden SPR-1002 - SPR-1003 - John Michael Talbot - John Michael Talbot [1976] He Is Risen/Jerusalem/How Long/Would You Crucify Him//Woman/Greewood Suite/Hallelu SPR-1004 - Firewind - Various Artists [1976] Artists include Anne Herring, Barry McGuire, John Talbot, Keith Green, Matthew Ward, Nelly Ward, and Terry Talbot (In other words, Barry McGuire, The Talbot Brothers, Keith Green, and The 2nd Chapter of Acts). -

The Lost Boy: Hartley Coleridge As a Symbol of Romantic Division

Halsall, Martyn (2009) The Lost Boy: Hartley Coleridge as a Symbol of Romantic Division. In: Research FEST 2009, July 2009, University of Cumbria. Downloaded from: http://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/840/ Usage of any items from the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository ‘Insight’ must conform to the following fair usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository Insight (unless stated otherwise on the metadata record) may be copied, displayed or performed, and stored in line with the JISC fair dealing guidelines (available here) for educational and not-for-profit activities provided that • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. The full policy can be found here. Alternatively contact the University of Cumbria Repository Editor by emailing [email protected]. The Lost Boy: Hartley Coleridge as a Symbol of Romantic Division. Dr Martyn Halsall Late one freezing evening in 1798 the writer Samuel Taylor Coleridge was completing a poem. -

Willing Suspension of Disbelief? a Study of the Role of Volition in the Experience of Delving Into a Story

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298068504 Willing Suspension of Disbelief? A study of the role of volition in the experience of delving into a story Research · March 2016 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1046.1843 CITATIONS READS 0 4,182 1 author: Itai Leigh Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1 PUBLICATION 0 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Itai Leigh on 13 March 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 30/09/2015 Contextualizing Paper for MA Practical Project module MA Acting (International) (EA606-G-SU) East15 Acting School Itai Leigh (PG 145747) Monologue Tutor: Zois Pigadas University of Essex Head of Course: Robin Sneller Willing Suspension of Disbelief? A study of the role of volition in the experience of delving into a story “The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary. Now you're looking for the secret... but you won't find it, because of course you're not really looking. You don't really want to know. You want to be fooled.” — The Prestige, Director Christopher Nolan, 2006 In this paper I present several angles, trying to understand the degree and the nature of will that takes place in the suspension of disbelief, or in immersion into a narrative we receive. I believe an understanding of the nature of the phenomenon can be, apart from intellectually interesting, doubly beneficial for actors. On one hand it is clearly desirable to have the power to modify the extent to which an audience would tend to get rapt or lost in a project we are creating (whether to elevate it for a more emotional reaction, or reduce it to allow more intellectual deliberation about its themes). -

Link to Coleridge Poems

1 Poems for S. T. Coleridge Edward Sanders 1. Coleridge won a medal his 1st year in college (Cambridge 1792) for a “Sapphic Ode on the Slave Trade” 2. Pantisocracy Sam Coleridge and Bob Southey conceived of Pantisocracy in 1794 just five years after the beautiful tearing down of the Bastille twelve couples would found an intentional community on the Susquehanna River which flows from upstate New York ambling for hundreds of miles down thru Pennsylvania & emptying into the Chesapeake Bay The plan was to work maybe 2-3 hours a day with sharing of chores Each couple had to come up with 125 pounds So Southey & Coleridge strove to earn their shares through writing C. wrote to Southey 9-1-94 2 that Joseph Priestly might join the Pantisocrats in America The scientist-philosopher had set up a “Constitution Society” to advocate reform of Parliament inaugurated on Bastille Day 1791 Then “urged on by local Tories” a mob attacked & burned Priestly’s books, manuscripts laboratory & home so that he ultimately fled to the USA. 3. Worry-Scurry for Expenses In Coleridge from his earliest days worry-scurry for expenses relying on say a play about Robespierre writ w/ Southey in ’94 (around the time Robe’ was guillotined) to pay for their share of Pantisocracy on the Susquehanna & thereafter always reliant on Angels & the G. of S. Generosity of Supporters & brilliance of mouth all the way thru the hoary hundreds 3 4. Coleridge & Southey brothers-in-law —the Fricker sisters, Edith & Sarah Coleridge & Sarah Fricker married 10-4-95 son Hartley born September 19, 1996 short-lived Berkeley in May 1998 Derwent Coleridge on September 14, 1800 & Sara on Dec 23, ’02 5. -

An Ecocritical Reading of William Wordsworth's Selected Poems

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 4, No. 1; 2014 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education An Ecocritical Reading of William Wordsworth’s Selected Poems Abolfazl Ramazani1 & Elmira Bazregarzadeh1 1 English Department, Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Tabriz, Iran Correspondence: Elmira Bazregarzadeh, Tamine Ejtemaiee Alley, Enghelab Avenue, Marvdasht 73716-48977, Fars, Iran. Tel: 98-728-333-5565. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 8, 2013 Accepted: December 12, 2013 Online Published: February 20, 2014 doi:10.5539/ells.v4n1p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v4n1p1 Abstract With the publication of Lawrence Buell’s The Environmental Imagination (1995) and Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm’s joint collection, The Ecocriticism Reader (1996), Ecocriticism emerged in the 1990s and the critics changed their angles of vision and examined the works of art by focusing on the relationship between man and Nature. Hence, Romantic poetry, in general, and William Wordsworth, in particular, became the key icons of ecocritical studies. Wordsworth was a major English Romantic poet who has been considered as a forerunner of English Romanticism. His views towards Nature and man’s treatment of Nature have supported his position as an important icon of ecocritical studies. His fame lies in the general belief that he has been viewed as a Nature poet who viewed Nature superior to humans. In other words, his views about Nature and his poems seek to heal the long-forgotten wounds of Nature in the hope of reaching unification between man and Nature. Therefore, this study is an attempt to focus on Wordsworth’s selected poems in the light of Ecocriticism in order to shed light on the poet’s cautious views about the interdependence of man and Nature and purge Wordsworth of the unjust labels tagged to him as a self-centered poet. -

Lyrical Ballads Theme: a Close Reading

Discovering Literature www.bl.uk/discovering-literature Teachers’ Notes Author / Work: William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads Theme: A Close Reading Rationale Lyrical Ballads, first published in 1798, has been described by the journalist Nicholas Lezard as ‘quite simply, possibly the single most important collection of poems in English ever published’. It grew out of the friendship and artistic collaboration between William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, but Wordsworth – who contributed most of the poems and whose Preface to the 1800 edition outlines the aesthetic intention of Lyrical Ballads – was its guiding force. In this lesson, students will explore a number of poems from Lyrical Ballads in the light of Wordsworth’s key philosophies, considering the extent to which Wordsworth and Coleridge succeeded in putting these philosophies into practice. Content Literary and historical sources: - The 1798 edition of Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, containing the Advertisement, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ and ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ - The 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, containing the Preface, notes to ‘The Thorn’ and extracts from ‘The Thorn’, and a note to ‘The Ancient Mariner’ - ‘We Are Seven’ by William Wordsworth, printed in William Hazlitt’s Select British Poets, or New Elegant Extracts (1824) Recommended reading (short articles): The Romantics by Stephanie Forward William Wordsworth, ‘Tintern Abbey’ by Philip Shaw External links: BBC Radio 4, ‘In Our Time’ – discussion of Lyrical Ballads Nicholas Lezard – review of Fiona Stafford’s edition of Lyrical Ballads, The Guardian, 16 July 2013 Further reading: James A. -

Wordsworth's Subliminal Lyric

Haunted Metre: Wordsworth’s Subliminal Lyric by Adrian Harding (Université de Provence & American University in Paris) Given Wordsworth’s condemnation, in the 1800 Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, of the “frantic novels, sickly and stupid German tragedies, and deluges of idle and extravagant stories in verse,” exciting the reading public’s “degrading thirst after outrageous stimulation” (LB 249), it has been customary to approach his relations to the Gothic in terms of readerships, grounded on or eventually grounding a sociology of reception. In this paper I am assuming the transference of the Gothic charge more intimately upon Coleridge, despite the latter’s own disparagement of the seductions of Gothic literature, as in the (perhaps strategic) letter of 27 December 1802 to Mary Robinson: “My head turns giddy, my heart sickens at the very thought of seeing such books in the hands of a child of mine” (Griggs, 94). The terms of Coleridge's condemnation of the Gothic provide a counterpart to Wordsworth's lyric phenomenology: “combinations of the highest sensation, wonder produced by supernatural power, without the means—thus gratifying our instinct of free-will that would fain be emancipated from the thraldom of ordinary nature—& and would indeed annihilate both space & time” (Notebooks 3449). What interests me here are the ways in which Wordsworth works with familiar, not unfamiliar, spirits, in a bringing up of language from what Hegel in The Philosophy of Spirit calls the “night-like mine” or “unconscious pit” (Hegel §453) from which signs emerge, to “the light of things” (“The Tables Turned”), the emancipations and annihilations operating from within “metrical language” to motivate any possible incursion or excursion through “ordinary nature”, any possible space and time of writing, any signs of a presence. -

Mohammad Sultan Ferdous Bahar ID: 2016235005

The Superhuman Character of Nature Playing Superlative Role in William Wordsworth’s Poems Mohammad Sultan Ferdous Bahar ID: 2016235005 Supervised By: Md. Minhazul Islam, Lecturer School of Liberal Arts and Social Science Dept. of English Rajshahi Science and Technology University, Natore. A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in English. Rajshahi Science and Technology University (RSTU), Natore June 2017 Language in India www.languageinindia.com <70-120> Vol. 17 Issue 8 Aug 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis titled “The Superhuman Character of Nature Playing Superlative Role in William Wordsworth’s Poems” has been composed by me in partial fulfillment of the requirements for M.A in English Literature Degree at Rajshahi Science and Technology University (RSTU), Natore. I would like to ensure that this thesis has been completely composed by me and made for the first time. I also acknowledge that I have duly cited all the references I have taken from different sources. Name of the Candidate: Mohammad Sultan Ferdous Bahar. ID: 2016235005 Name of the Degree: Master of Arts. Title of the Dissertation: “The Superhuman Character of Nature Playing Superlative Role in William Wordsworth’s Poems” Course Code: ENG-800 Field of Study/ Department: English (Literature) Candidate’s Signature: ............................. Date: ..................................... Language in India www.languageinindia.com <70-120> Vol. 17 Issue 8 Aug 2017 Acknowledgement It is of my pleasure that I have completed my thesis successfully by the grace of Allah despite many limitations. In doing my works, I have been assisted from various corners. -

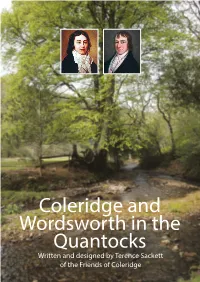

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks Written and designed by Terence Sackett of the Friends of Coleridge Why did the two poets choose the Quantocks? Samuel Taylor Coleridge first visited Nether Stowey in 1794, while on a walking A fine country house for the Wordsworths tour of Somerset with the poet Robert Southey. Crossing the River Parrett at Coleridge first met William Wordsworth in Combwich, they visited Coleridge’s Cambridge friend Henry Poole at Shurton. Bristol. The two poets took to each other Henry Poole took them to Nether Stowey where Coleridge was introduced to immediately. the man who was to be his most faithful friend and supporter – the tanner and In 1797 Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy Stowey benefactor Thomas Poole. were renting a country house at Racedown Poole accompanied them on a visit to the home of his conventional cousins at in West Dorset. Coleridge, keen to renew nearby Marshmills. The poets shocked them with their radical republican views and deepen the friendship, rushed down to and support for the French Revolution – England was at war with France at the persuade them to move to the Quantocks. Thomas Poole time and there was a serious threat of a French invasion. They found his enthusiasm impossible to resist. Once again Tom Poole was given the task CHRISTIE’S A poor choice of cottage of finding a house for the Wordsworths to Alfoxden House, near Holford to rent. Alfoxden, just outside the village of In 1796 Samuel Taylor Coleridge was living in Bristol. ‘There is everything here, sea, woods wild as fancy Holford and four miles from Stowey, could In his characteristically courageous and foolhardy ever painted, brooks clear and pebbly as in not have been more different to Gilbards. -

A Poetics of Dissent; Or, Pantisocracy in America Colin Jager

A Poetics of Dissent; or, Pantisocracy in America Colin Jager Theory and Event 10:1 | © 2007 To know a bit more about the threads that trace the ordinary ways and forgotten paths of utopia, it would be better to follow the labor of the poets. -- Jacques Ranciere, Short Voyages to the Land of the People The past can be seized only as an image, which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again. -- Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History 1. "Pantisocracy" was an experiment in radical utopian living, invented in England in the closing years of the eighteenth century by a couple of young poets, never put into practice, and described in later, more sober years with a mixture of embarrassment and shame by the poets and their friends, and with sanctimonious anger by their enemies. In the essay that follows I will interpret Pantisocracy as an example of what I call a "poetics of dissent" -- that is, a literary strategy that makes possible a dissenting politics. Immediately, however, it needs to be made clear that both "literary" and "politics" are understood broadly here; indeed, the politics I pursue is simply the possibility of speaking in a certain way. Moreover this essay bears a complicated relationship to a systematic exposition or exegesis, for although certain thinkers -- Derrida, Ranciere, Benjamin, Hardt and Negri -- appear here, I employ them opportunistically. The goal is to describe Pantisocracy in such a way as to create an historical "image" (in Benjamin's sense of the word) of dissent.