Kinetics and Catalysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21St Century

Opportunities for Catalysis in The 21st Century A Report from the Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee BASIC ENERGY SCIENCES ADVISORY COMMITTEE SUBPANEL WORKSHOP REPORT Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21st Century May 14-16, 2002 Workshop Chair Professor J. M. White University of Texas Writing Group Chair Professor John Bercaw California Institute of Technology This page is intentionally left blank. Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................... v A Grand Challenge....................................................................................................... v The Present Opportunity .............................................................................................. v The Importance of Catalysis Science to DOE.............................................................. vi A Recommendation for Increased Federal Investment in Catalysis Research............. vi I. Introduction................................................................................................ 1 A. Background, Structure, and Organization of the Workshop .................................. 1 B. Recent Advances in Experimental and Theoretical Methods ................................ 1 C. The Grand Challenge ............................................................................................. 2 D. Enabling Approaches for Progress in Catalysis ..................................................... 3 E. Consensus Observations and Recommendations.................................................. -

Dehydrogenation by Heterogeneous Catalysts

Dehydrogenation by Heterogeneous Catalysts Daniel E. Resasco School of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science University of Oklahoma Encyclopedia of Catalysis January, 2000 1. INTRODUCTION Catalytic dehydrogenation of alkanes is an endothermic reaction, which occurs with an increase in the number of moles and can be represented by the expression Alkane ! Olefin + Hydrogen This reaction cannot be carried out thermally because it is highly unfavorable compared to the cracking of the hydrocarbon, since the C-C bond strength (about 246 kJ/mol) is much lower than that of the C-H bond (about 363 kJ/mol). However, in the presence of a suitable catalyst, dehydrogenation can be carried out with minimal C-C bond rupture. The strong C-H bond is a closed-shell σ orbital that can be activated by oxide or metal catalysts. Oxides can activate the C-H bond via hydrogen abstraction because they can form O-H bonds, which can have strengths comparable to that of the C- H bond. By contrast, metals cannot accomplish the hydrogen abstraction because the M- H bonds are much weaker than the C-H bond. However, the sum of the M-H and M-C bond strengths can exceed the C-H bond strength, making the process thermodynamically possible. In this case, the reaction is thought to proceed via a three centered transition state, which can be described as a metal atom inserting into the C-H bond. The C-H bond bridges across the metal atom until it breaks, followed by the formation of the corresponding M-H and M-C bonds.1 Therefore, dehydrogenation of alkanes can be carried out on oxides as well as on metal catalysts. -

Sustainable Catalysis

Green Process Synth 2016; 5: 231–232 Book review Sustainable catalysis DOI 10.1515/gps-2016-0016 Sustainable catalysis provides an excellent in-depth over- view of the applications of non-endangered elements in Michael North (Ed.) all aspects of catalysis from heterogeneous to homogene- Sustainable catalysis: with non-endangered metals ous, from catalyst supports to ligands. The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2015 Four volumes of the book series are divided into RSC Green Chemistry series nos. 38–41 two sub-topics devoted to (i) metal-based catalysts and Part 1 (ii) catalysts without metals or other endangered ele- Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-638-1 ments. Each sub-topic comprises of two books due to the PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-211-6 detailed analysis of catalytic applications described. All Part 2 chapters are written by the world-leading researchers in Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-639-8 the area; however, covering far beyond the scope of their PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-642-8 immediate research interests, which makes the book par- ticularly valuable for a wide range of readers. Sustainable catalysis: without metals or other Sustainable catalysis: with non-endangered metals endangered elements begins with a very brief chapter which describes the Part 1 concept of elemental sustainability, overviewing the Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-640-4 abundance of the critical elements and perspectives on PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-209-3 sustainable catalysts. The chapters follow the groups of EPUB eISBN: 978-1-78262-752-4 the periodic table from left to right, from alkaline metals to Part 2 lead spanning 22 chapters. -

The Early History of Catalysis

The Early History of Catalysis By Professor A. J. B. Robertson Department of Chemistry, King’s College, London One hundred and forty years ago it was Berzelius proceeded to propose the exist- possible for one man to prepare an annual ence of a new force which he called the report on the progress of the whole of “catalytic force” and he called “catalysis” the chemistry, and for many years this task was decomposition of bodies by this force. This undertaken by the noted Swedish chemist is probably the first recognition of catalysis J. J. Berzelius for the Stockholm Academy of as a wide-ranging natural phenomenon. Sciences. In his report submitted in 1835 and Metallic catalysts had in fact been used in published in 1836 Berzelius reviewed a num- the laboratory before 1800 by Joseph Priestley, ber of earlier findings on chemical change in the discoverer of oxygen, and by the Dutch both homogeneous and heterogeneous sys- chemist Martinus van Marum, both of whom tems, and showed that these findings could be made observations on the dehydrogenation of rationally co-ordinated by the introduction alcohol on metal catalysts. However, it seems of the concept of catalysis. In a short paper likely that these investigators regarded the summarising his ideas on catalysis as a new metal merely as a source of heat. In 1813, force, he wrote (I): Louis Jacques Thenard discovered that ammonia is decomposed into nitrogen and “It is, then, proved that several simple or compound bodies, soluble and insoluble, have hydrogen when passed over various red-hot the property of exercising on other bodies an metals, and ten years later, with Pierre action very different from chemical affinity. -

Physical Organic Chemistry

CHM 8304 Physical Organic Chemistry Catalysis Outline: General principles of catalysis • see section 9.1 of A&D – principles of catalysis – differential bonding 2 Catalysis 1 CHM 8304 General principles • a catalyst accelerates a reaction without being consumed • the rate of catalysis is given by the turnover number • a reaction may alternatively be “promoted” (accelerated, rather than catalysed) by an additive that is consumed • a heterogeneous catalyst is not dissolved in solution; catalysis typically takes place on its surface • a homogeneous catalyst is dissolved in solution, where catalysis takes place • all catalysis is due to a decrease in the activation barrier, ΔG‡ 3 Catalysts • efficient at low concentrations -5 -4 -5 – e.g. [Enz]cell << 10 M; [Substrates]cell < 10 - 10 M • not consumed during the reaction – e.g. each enzyme molecule can catalyse the transformation of 20 - 36 x 106 molecules of substrate per minute • do not affect the equilibrium of reversible chemical reactions – only accelerate the rate of approach to equilibrium end point • most chemical catalysts operate in extreme reaction conditions while enzymes generally operate under mild conditions (10° - 50 °C, neutral pH) • enzymes are specific to a reaction and to substrates; chemical catalysts are far less selective 4 Catalysis 2 CHM 8304 Catalysis and free energy • catalysis accelerates a reaction by stabilising a TS relative to the ground state ‡ – free energy of activation, ΔG , decreases – rate constant, k, increases • catalysis does not affect the end point -

Concepts and Tools for Mechanism and Selectivity Analysis in Synthetic Organic Electrochemistry

Concepts and tools for mechanism and selectivity analysis in synthetic organic electrochemistry Cyrille Costentina,1,2 and Jean-Michel Savéanta,1 aUniversité Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Laboratoire d’Electrochimie Moléculaire, Unité Mixte de Recherche Université–CNRS 7591, 75205 Paris Cedex 13, France Contributed by Jean-Michel Savéant, April 2, 2019 (sent for review March 19, 2019; reviewed by Robert Francke and R. Daniel Little) As an accompaniment to the current renaissance of synthetic organic sufficient to record a current-potential response but small electrochemistry, the heterogeneous and space-dependent nature of enough to leave the substrates and cosubstrates (of the order of electrochemical reactions is analyzed in detail. The reactions that follow one part per million) almost untouched. Competition of the the initial electron transfer step and yield the products are intimately electrochemical/chemical events with diffusional transport under coupled with reactant transport. Depiction of the ensuing reactions precisely mastered conditions allows analysis of the kinetics profiles is the key to the mechanism and selectivity parameters. within extended time windows (from minutes to submicroseconds). Analysis is eased by the steady state resulting from coupling of However, for irreversible processes, these approaches are blind on diffusion with convection forced by solution stirring or circulation. reaction bifurcations occurring beyond the kinetically determining Homogeneous molecular catalysis of organic electrochemical reactions step, which are precisely those governing the selectivity of the re- of the redox or chemical type may be treated in the same manner. The same benchmarking procedures recently developed for the activation action. This is not the case of preparative-scale electrolysis accom- of small molecules in the context of modern energy challenges lead to panied by identification and quantitation of products. -

Electrochemistry and Photoredox Catalysis: a Comparative Evaluation in Organic Synthesis

molecules Review Electrochemistry and Photoredox Catalysis: A Comparative Evaluation in Organic Synthesis Rik H. Verschueren and Wim M. De Borggraeve * Department of Chemistry, Molecular Design and Synthesis, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200F, box 2404, 3001 Leuven, Belgium; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-16-32-7693 Received: 30 March 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019; Published: 5 June 2019 Abstract: This review provides an overview of synthetic transformations that have been performed by both electro- and photoredox catalysis. Both toolboxes are evaluated and compared in their ability to enable said transformations. Analogies and distinctions are formulated to obtain a better understanding in both research areas. This knowledge can be used to conceptualize new methodological strategies for either of both approaches starting from the other. It was attempted to extract key components that can be used as guidelines to refine, complement and innovate these two disciplines of organic synthesis. Keywords: electrosynthesis; electrocatalysis; photocatalysis; photochemistry; electron transfer; redox catalysis; radical chemistry; organic synthesis; green chemistry 1. Introduction Both electrochemistry as well as photoredox catalysis have gone through a recent renaissance, bringing forth a whole range of both improved and new transformations previously thought impossible. In their growth, inspiration was found in older established radical chemistry, as well as from cross-pollination between the two toolboxes. In scientific discussion, photoredox catalysis and electrochemistry are often mentioned alongside each other. Nonetheless, no review has attempted a comparative evaluation of both fields in organic synthesis. Both research areas use electrons as reagents to generate open-shell radical intermediates. Because of the similar modes of action, many transformations have been translated from electrochemical to photoredox methodology and vice versa. -

Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry

THE PERIODIC TABLE OF THE ELEMENTS OF GREEN AND SUSTAINABLE CHEMISTRY Paul T. Anastas Julie B. Zimmerman The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Copyright © 2019 by Paul T. Anastas and Julie B. Zimmerman All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information and contact; address www.website.com Published by Press Zero, Madison, Connecticut USA 06443 Cover Design by Paul T. Anastas ISBN: 978-1-7345463-0-9 First Edition: January 2020 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry To Kennedy and Aquinnah 3 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the entirety of the international green chemistry community for their efforts in creating a sustainable tomorrow. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Evan Beach for his thoughtful and constructive contributions during the editing of this volume, Ms. Kimberly Chapman for her work on the graphics for the table. In addition, the authors would like to thank the Royal Society of Chemistry for their continued support for the field of green chemistry. 4 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Clusters, Catalysis, and Materials: Kinetic, Superatomand

Frontiers in Chemical Physics Seminar Series Professor Will Castleman Presenting: Clusters, Catalysis, and Materials: Kinetic, Superatom and Isoelectronic Concepts Abstract During the course of investigating the reactivity and structure of metal and metal-compound clusters, we discovered the ability to mimic elements of the periodic table using selected species termed “superatoms”. The findings are being extended to binary metallic and compound systems, where both electronic and geometric structures are identified as playing a role in governing stability and the presence of reactive centers, the main subject of this lecture. As the behavior of clusters can be controlled by size and composition, the superatoms offer the potential to create unique compounds with tailored properties where each atom makes a difference. Having demonstrated the feasibility of this approach, one of the prime objectives of our current research is to lay the foundation for forming new nanoscale materials via techniques of cluster assembly utilizing these “elements” as the building blocks, utilizing knowledge we acquire about cluster reactions and properties which serve to identify promising species. This pursuit is viewed as one of the most promising frontiers in nanoscale materials research. Date: May 10th It is found that clusters of selected composition, stoichiometry, size and charge-state provide ideal media for investigating fundamental mechanisms of heterogeneous catalysis, especially for oxidation reactions. The interplay Location: EMSL AUD and unification of the ideas and concepts that enable the identification of catalytic mechanisms and the design of superatoms mimicking elements of the periodic table will be discussed, also with attention given to quantifying Time: 11:00 AM concepts through the isoelectronic principle.. -

Abiogenesis and Photostimulated Heterogeneous Reactions in The

Abiogenesis and Photostimulated Heterogeneous synthesize organic species in Interstellar Space on the Reactions in the Interstellar Medium and in the surface of dust particles (as they were on primitive Earth). Primitive Earth’s Atmosphere. Some peculiar features of heterogeneous photocatalytic Relevance to the Genesis of Life systems, namely (i) the considerable red shift of the spectral range of a given photoreaction compared with N. Serpone,1, 2 A. Emeline,1 V. Otroshchenko,3 one in homogeneous phase and (ii) the effect of spectral and V. Ryabchuk 4 selectivity of photocatalysts (5), favor the synthesis of 1 Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Concordia organic substrates under the above-mentioned natural University, Montreal (QC), Canada H3G 1M8. conditions. The first feature utilizes a considerably larger 2 Dipartimento di Chimica Organica, Universita di Pavia, fraction of Solar Energy than is otherwise possible in Pavia, Italia. homogeneous photochemical reactions. The second 3 Bach Institute of Biochemistry, Russian Academy of feature influences the dependence of the relative chemical Sciences, Moscow, Russia. yields of different products of a given reaction on the 4 Department of Physics, University of St.-Petersburg, wavelength of the actinic radiation. In particular, the St. Petersburg 198504, Russia. products of complete and partial oxidation of methane and other hydrocarbons result principally from the Studies of micrometeoritic particles captured by Earth photoexcitation of metal-oxide photocatalysts in the (i.e. ) absorption bands (strong at different geological times and discovered in Antarctica fundamental intrinsic have deduced that many organic substances necessary for absorption of UV and of blue light). More complex the Origin of Life on Earth are synthesized in Interstellar organic compounds are formed under irradiation of the catalysts in the absorption bands (weak to Space and are subsequently transported to Earth by extrinsic meteorites, comets, and cosmic dust (1). -

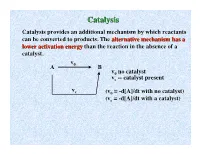

Catalysisatalysis Catalysis Provides an Additional Mechanism by Which Reactants Can Be Converted to Products

CCatalysisatalysis Catalysis provides an additional mechanism by which reactants can be converted to products. The alternative mechanism has a lower activation energy than the reaction in the absence of a catalyst. v A 0 B v0 no catalyst vc -- catalyst present v c (v0 = -d[A]/dt with no catalyst) (vc = -d[A]/dt with a catalyst) DE NotNot affected Energy barrier without catalyst by catalyst by catalyst Ea,f y g Ea,f and Ea,r r e Ea,f n are lowloweredered E l by a i t catalyst n e t E o a,r P Ea,r Ea,f ∆E Products Reactants Energy barrier with catalyst Reaction coordinate Generally a catalyst is defined as a substance which increases the rate of a reaction without itself being changed at the end of the reaction. This is strictly speaking not a good definition because some things catalyze themselves, but we will use this definition for now. Catalyst supplies a reaction path which has a lower activation energy than the reaction in the absence of a catalyst. CCaatatalylysissis bbyy EEnnzyzymmeses Enzymes may be loosely defined as catalysts for biological systems. They increase the rate of reactions involving biologically important systems. Enzymes are remarkable as catalysts because they are usually amazingly specific (work only for a particular kind of reaction.) They are also generally very efficient, achieving substantial Rate increases at concentrations as low as 10-8 M! Typical enzyme molecular weights are 104-106 gm/mole (protein molecules) SumSummmaryary ofof EnzymEnzymee CCharacteristicsharacteristics 1) Proteins of large to moderate weight 104 - 106. -

Factors Affecting the Relative Efficiency of General Acid Catalysis

Factors Affecting the Relative Efficiency of General Acid Catalysis Eugene E. Kwan Department of Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3H6, Canada* * Now at Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Electronic mail: [email protected] Abstract Specific acid catalysis (SAC) and general acid catalysis (GAC) play an important role in many organic reactions. Elucidation of SAC or GAC mechanisms requires an understanding of the factors that affect their relative efficiency. A simple model reaction in which SAC and GAC occur concurrently is analyzed to provide guidelines for such analyses. Simple rules which predict the effect of pH on the relative efficiency of GAC are discussed. An explicit expression for determining the optimal pH at which the effects of GAC are maximized is provided as well as an analogous expression for the general base case. The effects of the pKa of the general acid and the total catalyst concentration on GAC efficiency are described. The guidelines are graphically illustrated using a mixture of theoretical data and literature data on the hydrolysis of di-tert-butyloxymethylbenzene. The relationship between the model and the Brønsted equation is developed to explain the common observation that GAC is most easily observable when the Brønsted coefficient α is near 0.5. The ideas presented enable systematic evaluations of experimental kinetic data to provide quantitative support for SAC or GAC mechanisms. This material is suitable for the curriculum of a senior-level undergraduate course in physical-organic chemistry. Keywords: Organic chemistry; physical chemistry; curriculum; acid-base chemistry; catalysis; kinetics.