Mcdowell-2016-Sas-Discourses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Presentations & Masters Football Coaching

International Presentations & Masters Football Coaching: Switzerland, Germany, England, Denmark, France, Belgium, Italy, Qatar, Oman, Wales, USA, Guernsey, Jersey, Gibraltar, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Canada: Switzerland Hubball, H.T. (2019). Sustained Participation in a Grassroots International Masters 5-a- side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament (2006-2022); Performance Analysis in Advanced- level 55+ Football: Small-sided Game Competition. Invited presentation, FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association), Zurich, September. Hubball, H.T. (2008). The International Super Masters 5-a-side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament: Evolution & Sustainability. Keynote Address, 2008 International Masters World Cup, PE University of Zurich, Filzbach, May. Hubball, H.T. (2008). Masters/Veterans Soccer Communities: Local and Global Contexts. Feature research poster, International Symposium, Filzbach, Switzerland. Germany Hubball, H.T. (2019). Sustained Participation in a Grassroots International Masters 5-a- side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournament (2006-2022); Performance Analysis in Advanced- level 55+ Football: Small-sided Game Competition. Invited presentation, Bavarian Football Association, Munich, September. Hubball, H.T. (2012). Super Masters/Veterans 5-a-side Futsal World Cup Tournament: From Youth to Masters Team and Player Development in a Canadian Futsal Academy Program. Campus-wide presentation, German Sport University, Cologne, Germany, April. Denmark Hubball, H.T. (2019). Hosting the International Super Masters 5-a-side/Futsal World Cup Football Tournaments (2006-2022). Invited Presentation to the Executive Board of the Akademisk Boldklub FC, Denmark, May. Hubball, H.T., & Reddy. P (2015). Impact of walking football: Effective team strategies for high performance veteran players. 8th World Congress on Science and Football, Copenhagen, Denmark, May. France Hubball, H.T. -

Contents #110 1

Contents #110 1. Contents 2. Editorial #110 3. In this issue 4. Education News and Views 7. Good Practical Science John Holman 8. Irish Success at the International Chemistry Olympiad Odilla Finlayson 10. ARTIST - Action Research To Innovate Science Teaching Sarah Hayes, Peter Childs and Aimee Stapleton 12. Chemists you should know: #2 Niels Bohr – into atomic orbits Adrian J. Ryder 15. Classical Chemical Quotations #8 Niels Bohr 16. The world’s largest crystal model Robert Krickl 19. Teaching science in the USA Emma Ryan 23. Science Integration as a Precursor to Effective STEM education Miriam Hamilton 28. How does it work? The chemistry of the brown ring test for nitrate ions 30. TEMI idea: The amazing polydensity bottle 31. TEMI idea: The mystery of the disappearing precipitate 34. Zippie Chemistry Enda Carr 38. Places to visit Glengowla Mines, Co. Galway 40. Diary 41. Lithium the light metal powering the future – from brines to batteries ` Conference Reports 46. 10 th IViCE, Irish Variety in Chemistry Education Claire McDonnell 48. Science on Stage Europe Enda Carr 49. 11 th Chemistry Demonstration Workshop 51. 6th Annual BASF Summer School for Chemistry Teachers Declan Kennedy 53. 7th Eurovariety in University Chemistry Teaching Peter E. Childs 56. ESERA 2017 Peter E. Childs 58. Science at the National Ploughing Championships 2017 Aimee Stapleton, Martin McHugh, Sarah Hayes 60. Chemlingo: what’s in a name – nitre or natron? Peter E. Childs 61. The danger of cherry stones 62. The two faces of rubber 64. Information page Disclaimer The views expressed in Chemistry in Action! are those of the authors and the Editor is not responsible for any views expressed. -

3. All-Time Records 1955-2019

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE STATISTICS HANDBOOK 2019/20 3. ALL-TIME RECORDS 1955-2019 PAGE EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 1 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP PLAYER APPEARANCES 5 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP GOALSCORERS 8 NB All statistics in this chapter include qualifying and play-off matches. Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 58 FC Salzburg AUT 15 0 62 26 16 20 91 71 68 20 59 SV Werder Bremen GER 9 0 66 27 14 25 109 107 68 2 60 RC Deportivo La Coruña ESP 5 0 62 25 17 20 78 79 67 -1 Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD 61 FK Austria Wien AUT 19 0 73 25 16 32 100 110 66 -10 1 Real Madrid CF ESP 50 13 437 262 76 99 971 476 600 495 62 HJK Helsinki FIN 20 0 72 26 12 34 91 112 64 -21 2 FC Bayern München GER 36 5 347 201 72 74 705 347 474 358 63 Tottenham Hotspur ENG 6 0 53 25 10 18 108 79 60 29 3 FC Barcelona ESP 30 5 316 187 72 57 629 302 446 327 64 R. Standard de Liège BEL 14 0 58 25 10 23 87 73 60 14 4 Manchester United FC ENG 28 3 279 154 66 59 506 264 374 242 65 Sevilla FC ESP 7 0 52 24 12 16 86 73 60 13 5 Juventus ITA 34 2 277 140 69 68 439 268 349 171 66 SSC Napoli ITA 9 0 50 22 14 14 78 61 58 17 6 AC Milan ITA 28 7 249 125 64 60 416 231 314 185 67 FC Girondins de Bordeaux FRA 7 0 50 21 16 13 54 54 58 0 7 Liverpool FC ENG 24 6 215 121 47 47 406 192 289 214 68 FC Sheriff Tiraspol MDA 17 0 68 22 14 32 66 74 58 -8 8 SL Benfica POR 39 2 258 114 59 85 416 299 287 117 69 FC Dinamo 1948 ROU -

Three-Sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: a Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Pollock, Benjin (2021) Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/86739/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Three-sided Football and the Alternative Soccerscape: A Study of Sporting Space, Play and Activism Abstract: Three teams, three goals, and one ball. Devised as an illustrative example of ‘triolectics’, Danish artist and philosopher Asger Jorn conceived of three-sided football in 1962. However, the game remained a purely abstract philosophical exercise until the early 1990s when a group of anarchists, architects and artists decided to play the game for the first time. -

Frank Jensen Og Jesper Corneill

Master Thesis An inside perspective to the development of stock prices and business models for selected Danish football clubs Date 17th August 2011 Adviser Troels Troelsen, Institut for Produktion og Erhvervsøkonomi Students Frank Jensen - Cand.merc. Finance & Strategic Management ___________________________________________________ Jesper Corneille Dupont – Cand. merc. Finansiering & Regnskab ___________________________________________ No. of characters: 210.145 No. of figures: 47 No. of standardised pages: 109 Introduction 2 Executive Summery The purpose of this thesis was to analyse a selection of football stocks and their connection with different business models and a comparable stock index over the five year period from 2006 to 2010. The stock prices of football stocks have fluctuated a great deal, only two stocks managed to beat the comparable index between 2006 and 2008. From 2008 to 2010 no stocks proved to do considerably better than the comparable index. There is a high demand for the five football stocks since they are traded more than the comparable index over the past year. Meanwhile, the companies behind the five football shares have lost a great deal of the investor‟s capital. A statistical analysis proved that there was a correlation between the five football stocks, however from a practical perspective there was none. Accounting analysis of the selected clubs revealed a tendency towards spending every penny earned to achieve maximum success which caused the clubs to use different strategies. In an effort to understand the nature of the clubs, a model containing four different strategies was developed and applied to the clubs. There is no indication of a superior strategy or connection between the clubs‟ selected strategy and financial achievements. -

Årsberetning Telefax 4326 2245 E-Mail [email protected]

Dansk Boldspil-Union Udgiver Dansk Boldspil-Union Fodboldens Hus DBU Allé 1 2605 Brøndby Telefon 4326 2222 Årsberetning 2004 Telefax 4326 2245 e-mail [email protected] www.dbu.dk Redaktion DBU Kommunikation: Lars Berendt (ansvarshavende) Jacob Wadland Layout/dtp DBU Kommunikation: Bettina Wiechmann Lise Fabricius Fotos Årsberetning Per Kjærbye, Mikael Hauberg m.fl. Redaktion slut 1. januar 2005 Tryk Kailow Graphic 2004 Oplag 3.000 Pris Kr. 60,00 plus kr. 22,00 i forsendelse Dansk Boldspil-Union Indhold Dansk Boldspil-Union Dansk Boldspil-Union 2004 ....................................................................................... 4 U/19-kvindelandsholdet ............................................................................................ 50 Internationale relationer ............................................................................................. 7 U/17-pigelandsholdet ................................................................................................... 51 Medlemstal ..................................................................................................................... 10 Administrationen ........................................................................................................... 11 DBU Old Boys Organisationsplan ........................................................................................................ 12 Old Boys udvalget ........................................................................................................ 52 Bestyrelsen ...................................................................................................................... -

3.All-Time Records 1955-2016

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE STATISTICS HANDBOOK 2016/17 3. ALL-TIME RECORDS 1955-2016 PAGE EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 1 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP PLAYER APPEARANCES 5 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP GOALSCORERS 7 NB All statistics in this chapter include qualifying and play-off matches. Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 60 FC Girondins de Bordeaux FRA 7 0 50 21 16 13 54 54 58 0 61 FC Dinamo Bucureşti ROU 18 0 66 24 10 32 96 106 58 -10 62 Beşiktaş JK TUR 18 0 69 22 14 33 65 105 58 -40 63 ACF Fiorentina ITA 5 0 45 21 15 9 63 49 57 14 Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD 64 SS Lazio ITA 6 0 52 22 12 18 80 64 56 16 65 FK Dukla Praha CZE 10 0 45 22 10 13 75 58 54 17 1 Real Madrid CF ESP 47 11 398 237 69 92 875 425 543 450 66 HJK Helsinki FIN 18 0 64 22 10 32 78 103 54 -25 2 FC Bayern München GER 33 5 312 178 67 67 617 308 423 309 67 AEK Athens FC GRE 14 0 62 16 20 26 71 98 52 -27 3 FC Barcelona ESP 27 5 279 164 63 52 558 270 391 288 68 FC Salzburg AUT 12 0 48 20 11 17 62 55 51 7 4 Manchester United FC ENG 26 3 261 145 64 52 483 248 354 235 69 VfL Borussia Mönchengladbach GER 8 0 42 19 12 11 89 53 50 36 5 AC Milan ITA 28 7 249 125 64 60 416 231 314 185 70 Leeds United AFC ENG 4 0 40 22 6 12 76 41 50 35 6 Juventus ITA 31 2 239 116 62 61 377 236 294 141 71 FC Sheriff MDA 14 0 58 19 12 27 56 63 50 -7 7 SL Benfica POR 36 2 229 105 54 70 382 247 264 135 72 Manchester City FC ENG 7 0 45 19 -

B.93'S MEDLEMSBLAD Nr

B.93'S MEDLEMSBLAD Nr. 2, JUNI 2017 1 Næste blad Forsidebillede: Zoe og Sofie – vindere af forventes MEDLEMSBLAD FOR B.93 DM i Ungdomstennis for U12 og U18 Nr. 2 – juni 2017 Annoncer 15. Redaktionen af dette nummer er Jonas Klausen september afsluttet mandag 20. maj 2017. Mobil : 2750 8667 2017 [email protected] Deadline for Boldklubben af 1893 indlevering af stof Medlemsblad redaktionen B.93’s kontor Søndag den Ved Sporsløjfen 10 Gitte Arnskov 20. august 2100 København Ø Telefon : 3927 1890 2017 [email protected] Chefredaktør Torben Klarskov Kontorets åbningstider Telefon : 4814 4993 Mandag, tirsdag og torsdag kl. 12-18 [email protected] Fredag kl. 12-15 Redaktionsmedlemmer Banekontor Fodboldafdelingen Telefon : 3924 1893 Ole Helding Telefon : 2093 9637 Restaurant [email protected] Anette & Giacomo Musumeci Telefon : 3955 1322 Christian Winther Mobil : 2444 7919 Telefon : 2585 0595 [email protected] [email protected] Hjemmesideredaktion Palle ‘Banks’ Jørgensen Klaus B. Johansen Telefon : 4465 2885 [email protected] [email protected] Officielle hjemmesider Tennisafdelingen b93.dk Ledig fodbold.b93.dk copenhagenfootballcamp.dk Redaktionen er samlet ansvarlig over b93prof.dk for klubbens ledelse. b93tennis.dk Layout & Design –V18 Tryk Læs medlems- Marie Samuelsen Herrmann & Fischer bladet online på b93.dk/ Jesper Skipper Momme Se mere på hogf.dk medlemsbladet Illustrationer Designed by Freepik.com facebook.com/ b1893 Støt ungdomsfodbolden i B.93 Meld dig ind i Back-Op foreningen E. mail : [email protected] 2 Betal 1.000 kr. til Kontonummer 7872 4113721 (Kontingent for hele 2017) KLUBLIV 2018 Vi kan iagttage det alle vegne. Idrætsfor- eller et spil kort efter arbejdstid for siden eningernes samlingssteder står tomme. -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Eden Arena - Prague Tuesday 22 September 2020 21.00CET (21.00 local time) SK Slavia Praha Play-off, First leg FC Midtjylland Last updated 10/12/2020 17:34CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Squad list 5 Match officials 8 Fixtures and results 9 Match-by-match lineups 12 Team facts 13 Legend 15 1 SK Slavia Praha - FC Midtjylland Tuesday 22 September 2020 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Eden Arena, Prague Previous meetings Head to Head No UEFA competition matches have been played between these two teams SK Slavia Praha - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers SK Slavia Praha - F.C. 08/11/2018 GS 0-0 Prague Copenhagen F.C. Copenhagen - SK Slavia 25/10/2018 GS 0-1 Copenhagen Matoušek 46 Praha UEFA Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Akademisk Boldklub - SK Slavia 0-2 Dostálek 46, Tomáš 28/09/2000 R1 Søborg Praha agg: 0-5 Došek 90 SK Slavia Praha - Akademisk Kuchar 29, 73, Tomáš 14/09/2000 R1 3-0 Prague Boldklub Došek 52 FC Midtjylland - Record versus clubs from opponents' country FC Midtjylland have not played against a club from their opponents' country Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA SK Slavia Praha 2 1 1 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 3 1 0 6 0 FC Midtjylland 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 SK Slavia Praha - FC Midtjylland Tuesday 22 September 2020 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Eden Arena, Prague Match background Slavia Praha will have to overcome a Midtjylland side bidding to make their group stage debut if the Czech club are to rub shoulders with the UEFA Champions League elite for the second season running. -

Kampprogram 1

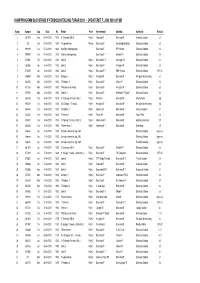

KAMPPROGRAM BLOVSTRØD IF FODBOLDAFDELING FORÅR 2010 - OPDATERET 7. JUNI 2010 AF MB Kamp Kampnr Dag Dato Kl. Række Pulje Hjemmehold Udehold Spillested Resultat 1 681591 Ons 07-04-2010 18:30 U-15 drenge (95) 4 Pulje 2 Græsted IF Blovstrød IF Græsted Stadion 4-2 2 702 Ons 07-04-2010 18:00 7-Superveteran Mester Blovstrød IF Høsterkøb Boldklub Blovstrød Stadion 3-2 3 999999 Ons 07-04-2010 18:30 Old Boys træningskamp Blovstrød IF FIF Hillerød Blovstrød Stadion 1-2 4 999999 Ons 07-04-2010 18:30 Veteran træningskamp Blovstrød IF Allerød FK Blovstrød Stadion 0-4 5 675664 Tor 08-04-2010 18:30 Serie 5 Pulje 3 Blovstrød IF 2 Helsingør FC Blovstrød Stadion 3-3 6 259883 Lør 10-04-2010 14:00 Serie 2 Pulje 1 Blovstrød IF Kvistgård IF Blovstrød Stadion 0-0 7 675595 Lør 10-04-2010 16:00 Serie 5 Pulje 2 Blovstrød IF 1 KBK Hillerød Blovstrød Stadion BIF UK 8 676999 Man 12-04-2010 18:30 Old boys 3 Pulje 2 Kvistgård IF Blovstrød IF Kvistgård Idrætsanlæg 4-1 9 664705 Man 12-04-2010 19:00 7-Old boys 2 Pulje 1 Blovstrød IF Ålholm IF Blovstrød Stadion 2-4 10 671216 Man 12-04-2010 19:00 7-Kvindesenior Mester Pulje 1 Blovstrød IF Kvistgård IF Blovstrød Stadion 5-2 11 677209 Man 12-04-2010 19:00 Veteran 1 Pulje 1 Blovstrød IF Birkerød IF "Skjold" Blovstrød Stadion 1-2 12 666146 Ons 14-04-2010 18:15 U-12 drenge 7-mands (98) 3 Pulje 2 Ålholm IF Blovstrød IF Ålholmskolen 5-8 13 895578 Ons 14-04-2010 18:30 DGI Oldboys - 7 mands Pulje 1 Kvistgård IF Blovstrød IF Kvistgård Idrætsanlæg 1-6 14 664491 Ons 14-04-2010 18:30 7-Old boys 1 Pulje 1 Gørløse SI Blovstrød IF Gørløse Stadion 2-1 15 664823 Ons 14-04-2010 18:30 7-Veteran 1 Pulje 1 Farum BK Blovstrød IF Farum Park 3-4 16 670427 Ons 14-04-2010 18:30 U-9 drenge 7-mands (2001) 2 Pulje 3 Albertslund IF Blovstrød IF Albertslund Stadion 2-7 17 663386 Ons 14-04-2010 19:00 7-Herresenior 1 Pulje 1 Hareskov IF 1 Blovstrød IF Birkevang 3-2 18 Stævne Lør 17-04-2010 10:00 5 mands stævne for årg 2004 Blovstrød Stadion Ingen res. -

Specifikation Af Kampe Mod: Nedenstående Oversigt Er En Specifikation Af Samtlige Holbæk B&I Og Nordvest FC-Modstandere Siden Efteråret 1931

Specifikation af kampe mod: Nedenstående oversigt er en specifikation af samtlige Holbæk B&I og Nordvest FC-modstandere siden efteråret 1931. Turnerings- og pokalkampe omfatter såvel DBU- og SBU-regi. AB Albertslund IF Akademisk Boldklub Albertslund Idrætsforening 2. division 0 - 0 H 3. division øst 1 - 1 H 1965 1988 2. division 1 - 1 U 3. division øst 3 - 0 U 2. division 1 - 0 H 3. division øst 3 - 1 H 1989 1972 2. division 1 - 1 U 3. division øst 1 - 1 U Landspokalen 2 - 2 U Danmarksserien 1 - 0 H 1991 2. division 2 - 2 H Danmarksserien 4 - 1 U 1978 2. division 1 - 3 U Danmarksserien 1 - 0 H 2001-02 2. division 3 - 2 H Danmarksserien 2 - 2 U 1979 2. division 1 - 2 U 2002 Landspokalen (SBU) 3 - 3 U Landspokalen 3 - 2 U 2. division 0 - 1 H 1980 Allerød FK 2. division 2 - 0 U Allerød Fodboldklub 2. division 1 - 0 H Serie 1 5 - 2 H 1981 1960 2. division 2 - 1 U Serie 1 4 - 1 U 3. division øst 2 - 1 H 2. division øst 2 - 0 H 1987 2009-10 3. division øst 2 - 4 U 2. division øst 2 - 1 U 3. division øst 1 - 0 H 2. division øst 2 - 2 H 1988 2010-11 3. division øst 2 - 1 U 2. division øst 3 - 0 U 3. division øst 2 - 1 H 1989 3. division øst 2 - 2 U Asnæs BK 3. division øst 4 - 1 H 1990 3. division øst 1 - 0 U Asnæs Boldklub 2008 Landspokalen 1 - 1 H 2011 Landspokalen 6 - 0 U 2. -

Medlemsblad B.93 NUMMER 2 – September 2012 (Redaktionen Er Samlet Ansvarlig Over for Klubbens Ledelse.)

Medlemsblad B.93 NUMMER 2 – September 2012 (Redaktionen er samlet ansvarlig over for klubbens ledelse.) Layout & Design : SKP – KTS : Monika Jakobsen, Niels Legaard Annoncer : Jørgen Bundgaard : 2043 1891 B.93's kontor : Gitte Arnskov : 3927 1890 Klubbens dygtige U 11 hold vinder Cordial Cup Fax : 2927 3011 i Wien med en finalesejr over selveste Bayern [email protected] München Kontoret er åbent : Tirsdag til torsdag : Kl. 12-16 B.93 MEDLEMSBLAD Nr. 2 – september 2012 Fredag : Kl. 12-15 Redaktionen af dette blad er afsluttet Banekontor : 20. august 2012 3929 1893 B.93 og redaktionens adresse : Restaurant : Ved Sporsløjfen 10 Anette og Giacomo Mosumeci : 2944 7919 2100 København Ø. Hjemmeside Redaktion : Ansvarshavende redaktør : www.b93.dk Torben Klarskov : 4814 5893 Torben Klarskov : [email protected] [email protected] Inder Sapru : [email protected] Teknisk redaktør : Trykning : Ole Helding : 2093 9637 Herrmann & Fischer [email protected] Næste blad forventes 15. november 2012 Billedredaktør : – deadline mandag den 20. oktober. Christian Winther : 2585 0595 [email protected] Bladet kan også læses på B.93’s hjemmeside Forretningsfører : Palle „Banks“ Jørgensen : 4465 2885 Støt Ungdomsfodbolden i B.93 [email protected] Meld dig ind i Back-Op foreningen E. mail : [email protected] Tennis : Betal 650 kr. til Konto 1551-4001273671 Kathrine Hertz Østergaard : 2095 2530 (Kontingent for 2. halvår for nye medlemmer) [email protected] 2 Nye udfordringer „Fodbold er hverken liv eller død – det er ti gange værre“, sagt af Liverpools legendariske mana- ger, Bill Shankly, og vi var mange neglebidende B.93’ere, der fulgte førsteholdets kamp for over- levelse i den yderst tætte 2.