Impacts from the World Administrative Radio Conference of 1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marc Brennan Thesis

Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia Marc Brennan, BA (Hons) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre (CIRAC) Thesis Submitted for the Completion of Doctor of Philosophy (Creative Industries), 2005 Writing to Reach You Keywords Journalism, Performance, Readerships, Music, Consumers, Frameworks, Publishing, Dialogue, Genre, Branding Consumption, Production, Internet, Customisation, Personalisation, Fragmentation Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia The music press and music journalism are rarely subjected to substantial academic investigation. Analysis of journalism often focuses on the production of news across various platforms to understand the nature of politics and public debate in the contemporary era. But it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to analyse all emerging forms of journalism in the same way for they usually serve quite different purposes. Music journalism, for example, offers consumer guidance based on the creation and maintenance of a relationship between reader and writer. By focusing on the changing aspects of this relationship, an analysis of music journalism gives us an understanding of the changing nature of media production, media texts and media readerships. Music journalism is dialogue. It is a dialogue produced within particular critical frameworks that speak to different readers of the music press in different ways. These frameworks are continually evolving and reflect the broader social trajectory in which music journalism operates. Importantly, the evolving nature of music journalism reveals much about the changing consumption of popular music. Different types of consumers respond to different types of guidance that employ a variety of critical approaches. -

Spring 2006 Bulletin 85

Advertisements Diary Dates Please refer to VLV when responding to advertisements. VLV Ltd cannot accept any liability or complaint in regard to the following offers. The charge for classified advertisements is 30p per word, 20p for Wednesday 26 April members. Please send typed copy with a cheque made payable to VLV Ltd. For display space please VLV Spring Conference contact Linda Forbes on 01474 352835. The Royal Society, London SW1 10.30am – 5.00pm The Radio Listener's Guide 2006 The Television Viewer's Guide 2006 Wednesday 26 April Presentation of VLV’s Awards G 160 pages G 160 pages for Excellence In Broadcasting G Frequencies for all BBC and commercial radio G Digital TV details of what you need to pick up Sky, The Royal Society, London SW1 stations, plus DAB digital transmitter details. Freeview or cable 1.45pm – 2.30pm G Radio Reviews Independent reviews of over G Transmitter sites for all analogue and digital Thursday, 11 May 130 radios including DAB digital radios. television transmitters. An Evening with Joan Bakewell G News from both BBC and commercial radio stations. G Equipment advice covering TV sets, VCRs, DVD One Whitehall Place, players and recorders, Sky and Freeview. G Digital Radio (DAB) The latest news and information. London SW1 G Freeview set-top box guide. 6.30pm – 8.20pm G Sky and Freeview radio information and G channel lists. Channel lists for Sky and Thursday, 18 May Freeview. VLV Evening Seminar with Mark G Advice showing how to get the G Thompson, BBC Director General best from your radio. -

Installation Guide, RMI-Q Radio Machine Interface

Installation guide H-5687-8504-03-A RMI-Q radio machine interface © 2012 – 2016 Renishaw plc. All rights reserved. This document may not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part, or transferred to any other media or language, by any means, without the prior written permission of Renishaw plc. The publication of material within this document does not imply freedom from the patent rights of Renishaw plc. Renishaw part no: H-5687-8504-03-A First issued: 11.2012 Revised: 07.2016 Contents i Before you begin ............................................................. 1.1 Before you begin ............................................................ 1.1 Disclaimer .............................................................. 1.1 Trade marks ............................................................. 1.1 Warranty ................................................................ 1.1 Changes to equipment ..................................................... 1.1 CNC machines ........................................................... 1.1 Care of the interface ....................................................... 1.1 RMP probe family ......................................................... 1.2 Patents ................................................................. 1.2 EC declaration of conformity ................................................... 1.3 WEEE directive ............................................................. 1.3 FCC Information to user (USA only) ............................................. 1.3 Radio approval ............................................................ -

Radio Evolution: Conference Proceedings September, 14-16, 2011, Braga, University of Minho: Communication and Society Research Centre ISBN 978-989-97244-9-5

Oliveira, M.; Portela, P. & Santos, L.A. (eds.) (2012) Radio Evolution: Conference Proceedings September, 14-16, 2011, Braga, University of Minho: Communication and Society Research Centre ISBN 978-989-97244-9-5 Live and local no more? Listening communities and globalising trends in the ownership and production of local radio 1 GUY STARKEY University of Sunderland [email protected] Abstract: This paper considers the trend in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in the world for locally- owned, locally-originated and locally-accountable commercial radio stations to fall into the hands of national and even international media groups that disadvantage the communities from which they seek to profit, by removing from them a means of cultural expression. In essence, localness in local radio is an endangered species, even though it is a relatively recent phenomenon. Lighter- touch regulation also means increasing automation, so live presentation is under threat, too. By tracing the early development of local radio through ideologically-charged debates around public-service broadcasting and the fitness of the private sector to exploit scarce resources, to present-day digital environments in which traditional rationales for regulation on ownership and content have become increasingly challenged, the paper also speculates on future developments in local radio. The paper situates developments in the radio industry within wider contexts in the rapidly-evolving, post-McLuhan mediatised world of the twenty-first century. It draws on research carried out between July 2009 and January 2011for the new book, Local Radio, Going Global, published in December 2011 by Palgrave Macmillan. Keywords: radio, local, public service broadcasting, community radio Introduction: distinctiveness and homogenisation This paper is mainly concerned with the rise and fall of localness in local radio in a single country, the United Kingdom. -

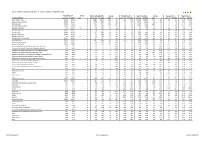

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 3 2019/Last Published Data

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2019/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share STATION/GROUP Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 Bauer Radio - Total 55032 55032 0 0% 18083 18371 288 2% 33% 33% 156216 158995 2779 2% 8.6 8.7 15.3% 15.9% Absolute Radio Network 55032 55032 0 0% 4743 4921 178 4% 9% 9% 35474 35522 48 0% 7.5 7.2 3.5% 3.6% Absolute Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 2151 2447 296 14% 4% 4% 16402 17626 1224 7% 7.6 7.2 1.6% 1.8% Absolute Radio (London) 12260 12260 0 0% 729 821 92 13% 6% 7% 4279 4370 91 2% 5.9 5.3 2.1% 2.2% Absolute Radio 60s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 125 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 298 n/a n/a n/p 2.4 n/p *% Absolute Radio 70s 55032 55032 0 0% 206 208 2 1% *% *% 699 712 13 2% 3.4 3.4 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 55032 55032 0 0% 1779 1824 45 3% 3% 3% 9294 9435 141 2% 5.2 5.2 0.9% 1.0% Absolute Radio 90s 55032 55032 0 0% 907 856 -51 -6% 2% 2% 4008 3661 -347 -9% 4.4 4.3 0.4% 0.4% Absolute Radio 00s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 209 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 540 n/a n/a n/p 2.6 n/p 0.1% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 55032 55032 0 0% 741 721 -20 -3% 1% 1% 3438 3703 265 8% 4.6 5.1 0.3% 0.4% Hits Radio Brand 55032 55032 0 0% 6491 6684 193 3% 12% 12% 53184 54489 1305 2% 8.2 8.2 5.2% 5.5% Greatest Hits Network 55032 55032 0 0% 1103 1209 106 10% 2% 2% 8070 8435 365 5% 7.3 7.0 0.8% 0.8% Greatest Hits Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 715 818 103 14% 1% 1% 5281 5870 589 11% 7.4 7.2 0.5% -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 15Th September 2019

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 15th September 2019 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 55,032,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % All Radio Q 48537 88 18.0 20.4 989221 100.0 All BBC Radio Q 33451 61 8.9 14.6 488274 49.4 All BBC Radio 15-44 Q 12966 51 4.6 8.9 115944 33.9 All BBC Radio 45+ Q 20485 69 12.5 18.2 372330 57.5 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 30828 56 7.7 13.8 425563 43.0 BBC Local Radio Q 7430 14 1.1 8.4 62711 6.3 All Commercial Radio Q 35930 65 8.6 13.2 475371 48.1 All Commercial Radio 15-44 Q 17884 71 8.5 12.0 214585 62.7 All Commercial Radio 45+ Q 18046 61 8.8 14.5 260786 40.3 All National Commercial1 Q 22361 41 3.8 9.5 211324 21.4 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 25988 47 4.8 10.2 264047 26.7 Other Radio Q 4035 7 0.5 6.3 25577 2.6 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Please note that the information contained within this quarterly data release has yet to be announced or otherwise made public Embargoed until 00.01 am and as such could constitute relevant information for the purposes of section 118 of FSMA and non-public price sensitive 24th October 2019 information for the purposes of the Criminal Justice Act 1993. -

©Copyright 2021 Mehrdad Hessar Platforms and Technologies for Low-Power Wireless Systems

©Copyright 2021 Mehrdad Hessar Platforms and Technologies for Low-Power Wireless Systems Mehrdad Hessar A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Shyamnath Gollakota, Chair Joshua R. Smith Tom Anderson Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science and Engineering University of Washington Abstract Platforms and Technologies for Low-Power Wireless Systems Mehrdad Hessar Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Shyamnath Gollakota Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering Achieving the vision of ubiquitous connectivity requires addressing multiple challenges across low-power wireless communication, network protocols and sensing. This thesis presents four tech- nologies that address some of the challenges in achieving ubiquitous connectivity. First, the thesis describes an ultra-low-power high-definition video streaming system that enables video stream- ing from a low-power, wearable camera to a nearby mobile device. Second, we present LoRa backscatter that enables the first wide-area backscatter communication system to achieve long- range low-power cheap wireless communication at tens of microwatts of power. Third, we build NetScatter, the first wireless protocol that can scale to hundreds and thousands of concurrent trans- missions from backscatter devices. Finally, we describe TinySDR platform, a standalone, fully programmable low power software-defined radio solution that can be duty cycled for battery op- eration like a real low-power sensor endpoint, and more importantly, can be programmed over the air to allow for large scale deployment. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures . iii List of Tables . viii Chapter 1: Introduction . -

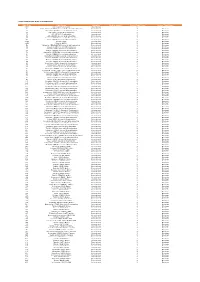

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 3Rd April 2016

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 3rd April 2016 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 53,575,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % All Radio Q 47823 89 18.8 21.0 1006462 100.0 All BBC Radio Q 34869 65 10.2 15.6 544682 54.1 All BBC Radio 15-44 Q 14423 57 5.8 10.2 147513 39.1 All BBC Radio 45+ Q 20446 72 14.1 19.4 397169 63.1 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 32014 60 8.8 14.7 469102 46.6 BBC Local Radio Q 8793 16 1.4 8.6 75580 7.5 All Commercial Radio Q 34277 64 8.1 12.7 434436 43.2 All Commercial Radio 15-44 Q 18057 71 8.6 12.0 217166 57.5 All Commercial Radio 45+ Q 16221 57 7.7 13.4 217270 34.5 All National Commercial1 Q 18220 34 2.7 8.1 147175 14.6 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 26884 50 5.4 10.7 287261 28.5 Other Radio Q 3816 7 0.5 7.2 27344 2.7 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Please note that the information contained within this quarterly data release has yet to be announced or otherwise made public Embargoed until 00.01 am and as such could constitute relevant information for the purposes of section 118 of FSMA and non-public price sensitive 19th May 2016 information for the purposes of the Criminal Justice Act 1993. -

FM 24-18. Tactical Single-Channel Radio Communications

FM 24-18 TABLE OF CONTENTS RDL Document Homepage Information HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, D.C. 30 SEPTEMBER 1987 FM 24-18 TACTICAL SINGLE- CHANNEL RADIO COMMUNICATIONS TECHNIQUES TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE II. CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO SINGLE-CHANNEL RADIO COMMUNICATIONS III. CHAPTER 2 RADIO PRINCIPLES Section I. Theory and Propagation Section II. Types of Modulation and Methods of Transmission IV. CHAPTER 3 ANTENNAS http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/24-18/fm24-18.htm (1 of 3) [1/11/2002 1:54:49 PM] FM 24-18 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I. Requirement and Function Section II. Characteristics Section III. Types of Antennas Section IV. Field Repair and Expedients V. CHAPTER 4 PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN OPERATING SINGLE-CHANNEL RADIOS Section I. Siting Considerations Section II. Transmitter Characteristics and Operator's Skills Section III. Transmission Paths Section IV. Receiver Characteristics and Operator's Skills VI. CHAPTER 5 RADIO OPERATING TECHNIQUES Section I. General Operating Instructions and SOI Section II. Radiotelegraph Procedures Section III. Radiotelephone and Radio Teletypewriter Procedures VII. CHAPTER 6 ELECTRONIC WARFARE VIII. CHAPTER 7 RADIO OPERATIONS UNDER UNUSUAL CONDITIONS Section I. Operations in Arcticlike Areas Section II. Operations in Jungle Areas Section III. Operations in Desert Areas Section IV. Operations in Mountainous Areas Section V. Operations in Special Environments IX. CHAPTER 8 SPECIAL OPERATIONS AND INTEROPERABILITY TECHNIQUES Section I. Retransmission and Remote Control Operations Section II. Secure Operations Section III. Equipment Compatibility and Netting Procedures X. APPENDIX A POWER SOURCES http://www.adtdl.army.mil/cgi-bin/atdl.dll/fm/24-18/fm24-18.htm (2 of 3) [1/11/2002 1:54:49 PM] FM 24-18 TABLE OF CONTENTS XI. -

Performing Right Society Limited Distribution Rules

PERFORMING RIGHT SOCIETY LIMITED DISTRIBUTION RULES PRS distribution policy rules Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 12 Scope of the PRS Distribution Policy ................................................................................ 12 General distribution policy principles ............................................................................. 12 Policy review and decision-making processes ............................................................. 13 DISTRIBUTION CYCLES AND CONCEPTS ................................................. 15 Standard distribution cycles and frequency .................................................................. 15 Distribution basis ..................................................................................................................... 15 Distribution sections ............................................................................................................... 16 Non-licence revenue ............................................................................................................... 16 Administration recovery rates ............................................................................................ 16 Donation to the PRS Foundation and Members Benevolent Fund ........................ 17 Weightings .................................................................................................................................. 17 Points and point values ......................................................................................................... -

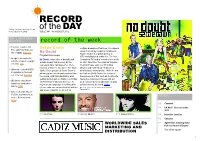

Record of the Week

Smiling Dancing Everything Is Free All You Need Is Positivity ISSUE 491 / 16 AUGUST 2012 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week TuneCore founders Jeff } Settle Down multiple broadsheet features. The superb Price and Peter Wells exit video directed by longterm collaborator the company. (Billboard) No Doubt Sophie Muller is a global priority at Polydor/Interscope MTV and playlisted at 4Music, The Box, } Google to de-emphasize No Doubt return after a decade with Chartshow TV, and a ‘record of the week’ websites of repeat copyright a radio smash that is every bit the on VH1. Over their five albums together offenders. (FT) comeback fans had hoped for. We’re No Doubt have sold over 45 million hooked, and we’re not alone. The Mark albums and notched up 10 Grammy Universal could sell all EMI } ‘Spike’ Stent produced Settle Down is nominations, winning twice. With the bar if regulators rip ‘the heart picking up an exceptional reaction from set high on Settle Down, the return of out of the deal’ (HypeBot) the media, with Kiss playlisting, and the purveyors of hits such as It’s My Life, getting its first spin on Radio1 on Friday Hella Good and Don’t Speak, will act UK albums chart shows } as Annie Mac’s ‘Special Delivery’. A as a massive dose of adrenalin for pop lowest one week sales in major press campaign is confirmed for junkies around the world. Video. history. (NME) release with covers on a host of fashion Released: September 16 (album; Push and Shove and music magazines, as well as September 24) } 64% of US under 18s use YouTube as primary music CONTENTS source, Nielsen reports.