Waiting to Vote Racial Disparities in Election Day Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher?

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher? JAMES MCKENZIE Texas Lyceum Fellow WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY? In the 2016 presidential election, Texas’ voter turnout Texas’ voter turnout is among placed near the bottom of all the states, ranking 47th. In the lowest in the nation. Texas’ recent 2018 mid-term election, which featured a Low turnout can lead to policies closely contested US Senate race and concurrent favoring the interests of gubernatorial election, not even half of eligible voters demographic groups whose (46.3%) participated.1 members are more likely to vote. Low voter turnout is not a recent phenomenon in Texas. Tex- There are deterrents to as has consistently lagged the national average in presidential registering and voting that the elections for voter turnout among the voting eligible popula- state can address. tion (VEP). In fact, since 2000, the gap between Texas’ turn- out and the national average consecutively widened in all but Policies such as same-day registration, automatic voter one election cycle.2 Texans may be open to changes to address registration, mail-in early voting, low turnout. According to a 2019 poll by the Texas Lyceum on and Election Day voting centers Texans’ attitudes toward democracy, a majority (61%) agreed could help. that “significant changes” are needed to make our electoral system work for current times.3 VOLUME 10 | ISSUE 6 | SEPTEMBER 2019 2 DOES VOTER TURNOUT MATTER? This report addresses ways to boost voter Voter turnout is often considered the curren- participation in both population sets. cy of democracy, a way for citizen’s prefer- ences to be expressed. -

Election Funding for 2020 and Beyond, Cont

Issue 64 | November-December 2015 can•vass (n.) Compilation of election Election Funding for 2020 returns and validation of the outcome that forms and Beyond the basis of the official As jurisdictions across the country are preparing for 2016’s results by a political big election, subdivision. election—2020 and beyond. This is especially true when it comes to the equipment used for casting and tabulating —U.S. Election Assistance Commission: Glossary of votes. Key Election Terminology Voting machines are aging. A September report by the Brennan Center found that 43 states are using some voting machines that will be at least 10 years old in 2016. Fourteen states are using equipment that is more than 15 years old. The bipartisan Presidential Commission on Election Admin- istration dubbed this an “impending crisis.” To purchase new equipment, jurisdictions require at least two years lead time before a big election. They need enough time to purchase a system, test new equipment and try it out first in a smaller election. No one wants to change equip- ment (or procedures) in a big presidential election, if they can help it. Even in so-called off-years, though, it’s tough to find time between elections to adequately prepare for a new voting system. As Merle King, executive director of the Center for Election Systems at Kennesaw State University, puts it, “Changing a voting system is like changing tires on a bus… without stopping.” So if elec- tion officials need new equipment by 2020, which is true in the majority of jurisdictions in the country, they must start planning now. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

Vote Center Training

8/17/2021 Vote Center Training 1 Game Plan for This Section • Component is Missing • Paper Jam • Problems with the V-Drive • Voter Status • Signature Mismatch • Fleeing Voters • Handling Emergencies 2 1 8/17/2021 Component Is Missing • When the machine boots up in the morning, you might find that one of the components is Missing. • Most likely, this is a connectivity problem between the Verity equipment and the Oki printer. • Shut down the machine. • Before you turn it back on, make sure that everything is plugged in. • Confirm that the Oki printer is full of ballot stock and not in sleep mode. • Once everything looks connected and stocked, turn the Verity equipment back on. 3 Paper Jam • Verify whether the ballot was counted—if it was, the screen will show an American flag. If not, you will see an error message. • Call the Elections Office—you will have to break the Red Sticker Seal on the front door of the black ballot box. • Release the Scanner and then tilt it up so that the voter can see the underside of the machine. Do not look at or touch the ballot unless the voter asks you to do so. • Ask the voter to carefully remove the ballot from the bottom of the Scanner, using both hands. • If the ballot was not counted, ask the voter to check for any rips or tears on the ballot. If there are none, then the voter may re-scan the ballot. • If the ballot is damaged beyond repair, spoil that ballot and re-issue the voter a new ballot. -

The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/50p7t4xg Author Guenther, Scott Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Scott M. Guenther Committee in charge: Professor James Fowler, Chair Professor Samuel Kernell, Co-Chair Professor Julie Cullen Professor Seth Hill Professor Thad Kousser 2016 Copyright Scott M. Guenther, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Scott M. Guenther is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To my parents. iv EPIGRAPH Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. { Benjamin Franklin v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................... iii Dedication...................................... iv Epigraph......................................v Table of Contents.................................. vi List of Figures................................... viii List of Tables.................................... ix Acknowledgements.................................x Vita........................................ -

The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It

IHS Political Science Series Working Paper 54 February 1998 The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart Impressum Author(s): Arend Lijphart Title: The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout - and What We Can Do About It ISSN: Unspecified 1998 Institut für Höhere Studien - Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) Josefstädter Straße 39, A-1080 Wien E-Mail: offi [email protected] Web: ww w .ihs.ac. a t All IHS Working Papers are available online: http://irihs. ihs. ac.at/view/ihs_series/ This paper is available for download without charge at: http://irihs.ihs.ac.at/1045/ Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 54 The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout – and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart 2 — Arend Lijphart / The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout — I H S The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout – and What We Can Do About It Arend Lijphart Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Political Science Series No. 54 February 1998 Prof. Dr. Arend Lijphart Department of Political Science, 0521 University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California 92093–0521 USA e-mail: [email protected] Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna 4 — Arend Lijphart / The Problem of Low and Unequal Voter Turnout — I H S The Political Science Series is published by the Department of Political Science of the Austrian Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS) in Vienna. The series is meant to share work in progress in a timely way before formal publication. -

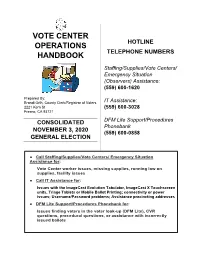

Vote Center Operations Handbook

VOTE CENTER HOTLINE OPERATIONS TELEPHONE NUMBERS HANDBOOK Staffing/Supplies/Vote Centers/ Emergency Situation (Observers) Assistance: (559) 600-1620 Prepared By: Brandi Orth, County Clerk/Registrar of Voters IT Assistance: 2221 Kern St (559) 600-3028 Fresno, CA 93721 DFM Lite Support/Procedures CONSOLIDATED Phonebank NOVEMBER 3, 2020 (559) 600-0858 GENERAL ELECTION ● Call Staffing/Supplies/Vote Centers/ Emergency Situation Assistance for: Vote Center worker issues, missing supplies, running low on supplies, facility issues ● Call IT Assistance for: Issues with the ImageCast Evolution Tabulator, ImageCast X Touchscreen units, Triage Tablets or Mobile Ballot Printing; connectivity or power issues; Username/Password problems; Assistance precincting addresses ● DFM Lite Support/Procedures Phonebank for: Issues finding voters in the voter look-up (DFM Lite), CVR questions, procedural questions, or assistance with incorrectly issued ballots TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................................................ 7 ELECTION DAY CHECKLIST & INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE OPENING ..................... 11 Quick Reference Check List for Opening Polls ................................................... 13 Oath and Payroll Form ........................................................................................ 14 Breaks ................................................................................................................. 15 Setting up the ImageCast Evolution -

BRNOVICH V. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BRNOVICH, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARIZONA, ET AL. v. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–1257. Argued March 2, 2021—Decided July 1, 2021* Arizona law generally makes it very easy to vote. Voters may cast their ballots on election day in person at a traditional precinct or a “voting center” in their county of residence. Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16–411(B)(4). Arizonans also may cast an “early ballot” by mail up to 27 days before an election, §§16–541, 16–542(C), and they also may vote in person at an early voting location in each county, §§16–542(A), (E). These cases involve challenges under §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) to aspects of the State’s regulations governing precinct-based election- day voting and early mail-in voting. First, Arizonans who vote in per- son on election day in a county that uses the precinct system must vote in the precinct to which they are assigned based on their address. See §16–122; see also §16–135. -

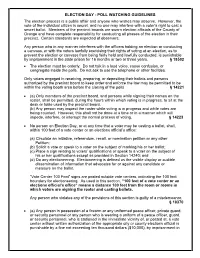

Election Day Poll Watching Guidelines

ELECTION DAY - POLL WATCHING GUIDELINES The election process is a public affair and anyone who wishes may observe. However, the vote of the individual citizen is secret, and no one may interfere with a voter's right to cast a secret ballot. Members of the precinct boards are sworn election officials of the County of Orange and have complete responsibility for conducting all phases of the election in their precinct. Certain standards are expected of observers: Any person who in any manner interferes with the officers holding an election or conducting a canvass, or with the voters lawfully exercising their rights of voting at an election, as to prevent the election or canvass from being fairly held and lawfully conducted, is punishable by imprisonment in the state prison for 16 months or two or three years. § 18502 The election must be orderly. Do not talk in a loud voice, cause confusion, or congregate inside the polls. Do not ask to use the telephone or other facilities. Only voters engaged in receiving, preparing, or depositing their ballots and persons authorized by the precinct board to keep order and enforce the law may be permitted to be within the voting booth area before the closing of the polls. § 14221 (a) Only members of the precinct board, and persons while signing their names on the roster, shall be permitted, during the hours within which voting is in progress, to sit at the desk or table used by the precinct board. (b) Any person may inspect the roster while voting is in progress and while votes are being counted. -

California Gubernatorial Recall Election Administration Guidance

SHIRLEY N. WEBER, Ph.D.| SECRETARY OF STATE | STATE OF CALIFORNIA ELECTIONS DIVISION th th 1500 11 Street, 5 Floor, Sacramento, CA 95814 | Tel 916.657.2166 | Fax 916.653.3214 | www.sos.ca.gov REVISED JULY 16, 2021 ELECTION ADMINISTRATION GUIDANCE RELATED TO THE SEPTEMBER 14, 2021, CALIFORNIA GUBERNATORIAL RECALL ELECTION Table of Contents I. Conducting the Election • In-person Voting Opportunities • Vote-by-Mail Ballot Drop-off Opportunities • Local Election Consolidation II. Voting Opportunities • Determination of Locations and Public Notice and Comment Period • SB 152/Section 1604 Waiver Process • Appointments • Drive-through Locations • Accessibility at In-person Locations • Polling Place Materials • Polling Locations - State and Local Government Facilities III. County Voter Information Guides • Preparation and Mailing • Content IV. Vote-By-Mail Ballots • Ballot Layout and Format Requirements • Ballot Tint and Watermark • Mailing • Tracking • Remote Accessible Vote-by-Mail (RAVBM) • Identification Envelope • Retrieval • Return (Postmark +7) • Processing V. Public Health and Safety VI. Poll Workers • Secretary of State • Counties VII. Voter Education and Outreach • Secretary of State • Counties REV 7/16/2021 VIII. Language Access • Secretary of State • Counties IX. Reporting Page 2 of 18 INTRODUCTION The Secretary of State issues this guidance document for the uniform conduct of the September 14, 2021, California Gubernatorial Recall Election. This guidance takes into consideration the recent enactment of Senate Bill 152 (SB 152) (Chapter 34 of the Statutes of 2021), which can be found at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220SB152 I. CONDUCTING THE ELECTION There are six different methods by which counties can conduct the September 14, 2021, California Gubernatorial Recall Election. -

Evaluating the Impact of Drop Boxes on Voter Turnout

Evaluating the Impact of Drop Boxes on Voter Turnout William McGuire, University of Washington Tacoma Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien, San Diego State University Katherine Baird, University of Washington Tacoma Benjamin Corbett, Lawrence Livermore Lab Loren Collingwood, University of California Riverside Voter turnout in the United States lags behind most other developed democracies. A popular approach for increasing turnout is to improve the ease of voting. While evidence indicates that vote by mail (VBM) requirements increase voter turnout, there is little evidence of the impact ballot drop boxes have on voting, despite the fact that voters in VBM states often prefer these boxes to voting via the postal service. All VBM states (currently Washington, Colorado and Oregon) require some provision for voting by drop boxes. This project examines the impact the installation of new ballot drop boxes had on voter turnout in Pierce County, the second largest county in Washington State. To identify the causal effects of these boxes on the decision to vote, we exploit the randomized placement of five new ballot drop boxes in Pierce prior to the 2017 general election. Voters selected to receive a new ballot drop box experienced an average reduction in distance to their nearest drop box of 1.31 miles. We estimate that this change in proximity to drop boxes increased voter turnout. Specifically, we find overall a 0.64 percentage point increase in voting per mile of distance to nearest drop box reduced. The effect, hence, is not a particularly large one. However, within the context of the very low turnout in Pierce County in 2017 and compared with alternative ways election officials have attempted to encourage more people to vote, this effect is not negligible. -

Electronic Voting: Methods and Protocols Christopher Andrew Collord James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2013 Electronic voting: Methods and protocols Christopher Andrew Collord James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Collord, Christopher Andrew, "Electronic voting: Methods and protocols" (2013). Masters Theses. 177. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/177 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Electronic Voting: Methods and Protocols Christopher A. Collord A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science InfoSec 2009 Cohort May 2013 Dedicated to my parents, Ross and Jane, my wife Krista, and my faithful companions Osa & Chestnut. ii Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge Krista Black, who has always encouraged me to get back on my feet when I was swept off them, and my parents who have always been there for me. I would also like to thank my dog, Osa, for sitting by my side for countless nights and weekends while I worked on this thesis—even though she may never know why! Finally, I would also like to thank all who have taught me at James Madison University. I believe that the education I have received will serve me well for many years to come.