Ken Burns' Civil War Author(S): Gabor S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ric Burns' Film Drawn from Oneonta Professor's Book

ReflectionsA PUBLICATION OF THE SUNY ONEONTA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION WINTER 2021 What's Inside: Ric Burns' Film Drawn From Oneonta Professor's Book Campaign Surpasses $17M Sustainable Fashion Week 2020 Brings Oneonta Voices to a Global Stage Alumni Weekend 2021 Reflections Volume LXXIV Number 2 Winter 2021 CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Reflections is published POSTMASTER Reflections Michelle Hansen Address service Vol. LXXIV three times a year by Lonnie Mitchell requested to: Number 2 the Division of College Kevin Morrow Reflections Winter 2021 Advancement and is Sandi Mulconry funded in part by the Office of Alumni MANAGING EDITOR Danielle Tonner ’95 SUNY Oneonta Alumni Engagement Laura M. Lincoln Benjamin Wendrow ’08 Association through Ravine Parkway charitable gifts to the SUNY Oneonta EDITORS CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Fund for Oneonta. Oneonta, NY Kevin Morrow Gerry Raymonda 13820-4015 Sandi Mulconry Michael Forester Rothbart SUNY Oneonta LEAD DESIGNER Illustrator Oneonta, NY 13820-4015 Reflections is printed Jonah Roberts David Owens Postage paid at on recycled paper. Oneonta, New York CONTENTS 2 10 20 FROM NETZER 301 FEATURE: TRENDS IN CAMPAIGN SURPASSES $17M HIGHER ED FUNDING IMPACT SUNY ONEONTA'S GROW. BUDGET THRIVE. LIVE. 12 THE FUTURE FEATURE: CAMP: 20 YEARS OF OF SUNY ONEONTA SUCCESS HELPING MIGRANT STUDENTS 26 FEATURE: OUR HEARTS GO 3 OUT TO THEM FROM THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 29 BEYOND THE PILLARS - Class Notes 4 - Celebrations ACROSS THE QUAD - In Memoriam - 2020 Sustainable Fashion Show - Driving While Black - Cornell-Gladstone-Hanlon- Kaufmann Lecture 40 - Community of Scholars ALUMNI PROFILE - Annual Alumni Association Latisha Nero ’09 Awards Celebration 14 2021 ALUMNI WEEKEND - Alumni Weekend 2021 Schedule - Alumni of Distinction Honorees - Annual Alumni Association Award Recipients On the Cover: Alumni of Distinction honoree Reconnect Gretchen Sorin ’75, director Follow the Alumni Association for news, events, of the Cooperstown Graduate contests, photos, and more. -

This Summer, American Public Television and WORLD Channel Transport Audiences to an African National Park That Is Saving Endange

This Summer, American Public Television and WORLD Channel Transport Audiences to an African National Park that is Saving Endangered Animals while Lifting Communities out of Poverty “Our Gorongosa” shares the stories of the women who are transforming conservation and development in Gorongosa National Park and providing the next generation of girls with opportunities for empowered futures Chevy Chase, MD (July 26, 2021) – “Our Gorongosa,” the inspirational film by Tangled Bank Studios and Gorongosa Media is debuting on public television stations across the country this summer and nationally on WORLD Channel, produced by GBH in partnership with the WNET Group in New York and distributed by American Public Television. Close to 90% of U.S. households will now be able to see the film on their local public television station (check local listings for eXact dates and airtimes). “Our Gorongosa” features Dominique Gonçalves, a vibrant Mozambican ecologist who runs the Gorongosa elephant ecology project as she shares the myriad ways Gorongosa is redefining the identity and purpose of an African national park. From her own work mitigating human/elephant conflict; to community clubs and school programs that empower girls to avoid teen marriage and pregnancy; to health clinics and nutrition training for eXpectant mothers and families; Dominique transforms viewers’ understanding of what a national park can be. The commitment of the remarkable women who run these programs—and the resilience of the mothers and girls who are benefiting from them—tell an inspiring story of strength and hope. “Our Gorongosa” has captivated film festival audiences since its debut at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and its festival premiere in 2019 at the Wild and Scenic Film Festival. -

"Perry H. Landon, 1841-1927" by Christopher Schwartz

Perry H Landon 1841- 1927 Kent County Maryland 7th United States Colored Troops Christopher Schwartz Washington College History 394-12/AMS 300-10 Professor Adam Goodheart 4/30/2013 On my honor I pledge to have abided by the Washington College Honor Code Signed: Schwartz 1 Perry H Landon was born in Kent county Maryland, a slave for life. Born in 1841 Landon would spend the first 22 years the property of slave owner named James Ricuad. As the Civil war became increasingly costly, many states loyal to the Union raised colored regiments. In 1863 in exchange for his freedom Perry Landon served in the 7th United States Colored Troop. Formed in Baltimore Maryland, the 7th U.S.C.T. would see constant action until the end of the war. The 7th would play a vital role in numerous battles as a part of the final push to capture Richmond and Petersburg, and eventually capture Robert E. lees Army of Northern Virginia. Perry Landon lost his right arm at the Battle of New Market Heights, a deadly battle, which resulted in the Union capture of Richmond. Unlike his white counterparts Landon would receive little recognition for his actions in combat. After returning home to Chestertown Maryland, Landon was confronted by a society that shunned free African Americans. All Civil War veterans were faced with a lack of social services and harsh reality of life in the post bellum United States. Wounded veterans faced a lack of health care and depending on the type of injury were unable earn decent wages. -

Doc Nyc Announces Full Line-Up for Fifth Edition, November 13-20, 2014

DOC NYC ANNOUNCES FULL LINE-UP FOR FIFTH EDITION, NOVEMBER 13-20, 2014 US Premiere of David Thorpe’s Do I Sound Gay? Opens Festival; US Premiere of Laura Nix and The Yes Men’s The Yes Men Are Revolting Will Close Event Four New Sections Announced With Expanded Features Line-up That Includes 19 World Premieres and 7 US Premieres Among Over 150 Films and Events World Premieres Include Amy Berg’s An Open Secret, Hank Rogerson & Jilann Spitzmiller’s Still Dreaming and Dan Rybicky & Aaron Wickenden’s Almost There Dozens of Filmmakers in Person to Present their Work Including Amy Berg, Joe Berlinger, Nick Broomfield, Ric Burns, Chris Hegedus, Rory Kennedy, Steve James, Albert Maysles, DA Pennebaker, Lucy Walker, and Frederick Wiseman; Other Special Guests Include Béla Fleck, Greg Louganis, Albie Sachs, Spandau Ballet, and The Yes Men NEW YORK, Oct. 15, 2014 – DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, announced the full line-up for its fifth edition, running November 13-20 at the IFC Center in Greenwich Village and Chelsea’s SVA Theatre and Bow Tie Chelsea Cinemas. Representing a dramatic growth from last year’s edition, the 2014 festival will showcase 153 films and events, with over 200 documentary makers and special guests expected in person to present their films to New York City audiences. DOC NYC is made possible by its sponsors, including Leadership Sponsor HBO Documentary Films; Media Sponsors WNET and New York magazine; and Major Sponsors A&E IndieFilms, History Films and SundanceNow Doc Club. The festival is produced by IFC Center. -

Lending Library

Lending Library KQED is pleased to present the Lending Library. Created expressly for KQED’s major donors, members of the Legacy Society, Producer’s Circle and Signal Society, the library offers many popular television programs and specials for home viewing. You may choose from any of the titles listed. Legacy Society, Producer’s Circle and Signal Society members may borrow VHS tapes or DVDs simply by calling 415.553.2300 or emailing [email protected]. For around-the-clock convenience, you may submit a request to borrow VHS tapes or DVDs through KQED’s Web site (www.KQED.org/lendinglibrary) or by email ([email protected]) or phone (415.553.2300). Your selection will be mailed to you for your home viewing enjoyment. When finished, just mail it back, using the enclosed return label. If you are especially interested in a program that is not included in KQED’s collection, let us know. However, because video distribution is highly regulated, not all broadcast shows are available for home viewing. We will do our best to add frequently requested tapes to our lending library. Sorry, library tapes are not for duplication or resale. If you want to purchase videotapes for your permanent collection, please visit shop.pbs.org or call 877-PBS-SHOP. Current listings were last updated in February 2009. TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTS 2 DRAMA 13 NEWS/PUBLIC AFFAIRS 21 BAY WINDOW 30 FRONTLINE 32 FRONTLINE WORLD 36 P.O.V. 36 TRULY CA 38 SCIENCE/NATURE 42 HISTORY 47 AMERICAN HISTORY 54 WORLD HISTORY 60 THE “HOUSE” SERIES 64 TRAVEL 64 COOKING/HOW TO/SELF HELP 66 FAQ 69 CHILDREN 70 COMEDY 72 1 ARTS Art and Architecture AGAINST THE ODDS: THE ARTISTS OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE (VHS) The period of the 1920s and ‘30s known as the Harlem Renaissance encompassed an extraordinary outburst of creativity by African American visual artists. -

The Heart of the Matter

american academy of arts & sciences The Heart of the Matter The Humanities and Social Sciences for a vibrant, competitive, and secure nation Who will lead America into a bright future? Citizens who are educated in the broadest possible sense, so that they can participate in their own governance and engage with the world. An adaptable and creative workforce. Experts in national security, equipped with the cultural understanding, knowledge of social dynamics, and language proficiency to lead our foreign service and military through complex global conflicts. Elected officials and a broader public who exercise civil political discourse, founded on an appreciation of the ways our differences and commonalities have shaped our rich history. We must prepare the next generation to be these future leaders. commission on the humanities and social sciences The Heart of the Matter american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts © 2013 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences All rights reserved. isbn: 0-87724-096-5 The views expressed in this volume are those held by the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Heart of the Matter is available online at http://www.amacad.org. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts & Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138-1996 Phone: 617-576-5000 Email: [email protected] www.amacad.org 5 Members of the Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences 6 Acknowledgments 9 Executive Summary 15 Introduction -

History of the City of New York Syllabus

History of the City of New York Columbia University- Fall 2001 Professor Kenneth T. Jackson History 4712 603 Fayerweather Hall Tues. & Thurs. 1:10pm-2:25pm- [email protected] 417 International Affairs Building “The city, the city my Dear Brutus – stick to that and live in its full light. Residence elsewhere, as I made up my mind in early life, is mere eclipse and obscurity to those whose energy is capable of shining in Rome.” Marcus Tullius Cicero “New York City, the incomparable, the brilliant star city of cities, the forty-ninth state, a law unto itself, the Cyclopean Paradox, the inferno with no out-of-bounds, the supreme expression of both the miseries and the splendors of contemporary civilization, the Macedonia of the United States. It meets the most severe test that may be applied to the definit ion of a metropolis – it stays up all night. But also it becomes a small town when it rains.” John Gunther “If you live in New York, even if you’re Catholic, you’re Jewish.” Lenny Bruce “There is no question there is an unseen world; the question is, how far is it from midtown, and how late is it open?” Woody Allen “I am not afraid to admit that New York is the greatest city on the face of God’s earth. You only have to look at it from the air, from the river, from Father Duffy’s statue. New York is easily recognizable as the greatest city in the world, view it any way and every way – back, belly, and sides.” Brendan Behan “Is New York the most beautiful city in the world? It is not far from it. -

Videorecordings Cataloging Workshop Introduction Introduction

Videorecordings Cataloging Workshop By Jay Weitz ([email protected]) Senior Consulting Database Specialist OCLC Online Computer Library Center For OLAC-MOUG Conference Cleveland, Ohio 2008 September 26-28 Introduction Not comprehensive AACR2 MARC Visual Materials Trying to be practical Introduction 1. Rules Background 6. Colorized Version, Letterboxed Version 2. Sources of Information 7. Closed Captioning, Audio Enhancement 3. When to Input a New 8. Summary Notes Record 9. DVDs, Other Videodiscs, 4. Music Videos: and Streaming Video Special Considerations 10. Television Series / 5. Physical Description Dependent Titles Introduction 11. Statements of 15. Genre Headings Responsibility 16. Locally-Made 12. Dates Videos 13. 007 17. In Analytics 14. Numbers 18. Collections 028 037 020 024 Rules Background 1 AACR2 Revised: Integrated Catalog AACR1: “Enter a motion picture under title” Title Main Entry for works of mixed responsibility Sources of Information 2 Title frames Container/Labels Be alert to differences in titles When to Input a New Record 3 Differences that Justify a New Record B&W vs. color (including colorized) Sound vs. silent Significantly different length Different machine/videorecording format (VHS vs. Beta vs. DVD, etc.) Changes in publication dates (Be careful that dates changes are not merely for packaging) Dubbed vs. subtitled Different language versions When to Input a New Record 3 Differences that Do Not Justify a New Record “Absence or presence of multiple publishers, distributors, etc., as long as one on the item matches one on the record and vice versa.” Edit existing record when in doubt Multiple Publishers/Distributors 3 5 245 00 Ozawa h [videorecording] / c a film by David Maysles .. -

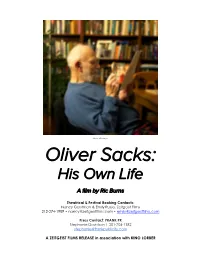

Oliver Sacks: His Own Life

Photo: Bill Hayes Oliver Sacks: His Own Life A film by Ric Burns Theatrical & Festival Booking Contacts: Nancy Gerstman & Emily Russo, Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 • [email protected] • [email protected] Press Contact: FRANK PR Stephanie Davidson | 201-704-1382 [email protected] A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE in association with KINO LORBER Vulcan Productions, Steeplechase Films, American Masters Pictures, Motto Pictures, Passion Pictures, and Tangled Bank Studios present Oliver Sacks: His Own Life Directed by Ric Burns Runtime: 114 Minutes Oliver Sacks: His Own Life Logline Oliver Sacks: His Own Life explores the life and work of the legendary neurologist and storyteller, as he shares intimate details of his battles with drug addiction, homophobia, and a medical establishment that accepted his work only decades after the fact. Sacks was a fearless explorer of unknown mental worlds who helped redefine our understanding of the brain and mind, the diversity of human experience, and our shared humanity. Short Synopsis A month after receiving a fatal diagnosis in January 2015, Oliver Sacks sat down for a series of filmed interviews in his apartment in New York City. For eighty hours, surrounded by family, friends, and notebooks from six decades of thinking and writing about the brain, he talked about his life and work, his abiding sense of wonder at the natural world, and the place of human beings within it. Drawing on these deeply personal reflections, as well as nearly two dozen interviews with close friends, family members, colleagues and patients, and archival material from every point in his life, this film is the story of a beloved doctor and writer who redefined our understanding of the brain and mind. -

Annual Report 2009

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Our Mission The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization supporting the study and love of American history through a wide range of programs and resources for students, teachers, scholars, and history enthusiasts throughout the nation. The Institute creates and works closely with history-focused schools; organizes summer seminars and development programs for teachers; produces print and digital publications and traveling exhibitions; hosts lectures by eminent historians; administers a History Teacher of the Year Award in every state and US territory; and offers national book prizes and fellowships for scholars to work in the Gilder Lehrman Collection as well as other renowned archives. Gilder Lehrman maintains two websites that serve as gateways to American history online with rich resources for educa - tors: www.gilderlehrman.org and the quarterly online journal www.historynow.org , designed specifically for K-12 teachers and students. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Advisory Board Co-Chairmen President Executive Director Richard Gilder James G. Basker Lesley S. Herrmann Lewis E. Lehrman Joyce O. Appleby, Professor of History Emerita, Ellen V. Futter, President, American Museum University of California, Los Angeles of Natural History Edward L. Ayers, President, University of Richmond Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University William F. Baker, President Emeritus, Educational Professor and Director, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Broadcasting Corporation African and African American Research, Thomas H. Bender, University Professor of Harvard University the Humanities, New York University S. Parker Gilbert, Chairman Emeritus, Morgan Stanley Group Carol Berkin, Presidential Professor of History, Allen C. Guelzo, Henry R. -

AM ABT ABT Production Biosfinal

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #ABTonPBS #AmericanMasters American Masters American Ballet Theatre: A History Premieres nationwide Friday, May 15 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) in honor of the company’s 75 th anniversary Production Biographies Ric Burns Director Director Ric Burns has been creating historical documentaries for public television for over 20 years. He began his career co-writing and producing the celebrated PBS series The Civil War (1990) with his brother Ken and Geoffrey C. Ward, and has since directed over 30 hours of award- winning films. Among his body of work are some of some of the most distinguished programs in the award-winning public television series American Experience , including Coney Island (1991); The Donner Party (1992); The Way West (1995); Ansel Adams (2002), a co-production of Steeplechase Films and Sierra Club Productions; We Shall Remain: Tecumseh’s Vision (2009), part two of a five-part history on Native Americans; and Into the Deep: America, Whaling and the World (2010). In 2006, Burns released both Eugene O’Neill and American Masters — Andy Warhol: A Documentary . The two films garnered 2006-2007 Primetime and News and Documentary Emmy Awards for Outstanding Writing for Non-Fiction Programming; Andy Warhol also received a 2006 Peabody Broadcasting Award. He is perhaps best known for his eight-episode, 17-and-a-half-hour series New York: A Documentary Film , which premiered nationally on PBS to wide public and critical acclaim when broadcast in November 1999, September 2001 and September 2003. -

Local Content and Service Report 2012 Empty Template

. 2015 LOCAL CONTENT AND SERVICE “Thanks for enriching my life with your wonderful programs!” REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY – Elaine B.,THIRTEEN Member Our Mission: Media with Impact Our Purpose: WNET is a multi-media public service non-profit that delivers life-long learning and meaningful experiences to our communities. Our content inspires curiosity, encourages action and nurtures dreams. LOCAL 2015 KEY LOCAL VALUE SERVICES IMPACT WNET’s mission “Media In 2015, WNET WNET had a deep with Impact” drives us continued its work local impact in 2015, to work as partners in producing quality reaching more than our community to programming on-air and 89 million viewers inspire positive change. online for both local monthly in the tri-state Whether expanding and national audiences area through stations local news and public in the areas of Arts, THIRTEEN, WLIW and affairs programming News and Public NJTV. through NJTV News or Affairs, Science and MetroFocus, high- Nature and Children’s. More than 65,000 New lighting local arts Special national series York educators organizations and focused on JFK and accessed curriculum- offerings through NYC- LBJ and Vietnam, ready resources for ARTS and Theater Treasures of New York, free from PBS Close-Up, or raising Off-Broadway theater LearningMedia New awareness and support and challenging issues York, featuring for solutions to the such as health and materials created by dropout crisis, WNET is wellness, the drop-out WNET. committed to our tri- crisis and local politics. state community. 2014 LOCAL CONTENT AND SERVICE REPORT Stories of Impact Dropout Crisis: American Graduate The fourth annual American Graduate Day took place on October 3, 2015.