L's 722 PS 009 601- R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genes in Eyecare Geneseyedoc 3 W.M

Genes in Eyecare geneseyedoc 3 W.M. Lyle and T.D. Williams 15 Mar 04 This information has been gathered from several sources; however, the principal source is V. A. McKusick’s Mendelian Inheritance in Man on CD-ROM. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Other sources include McKusick’s, Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders. Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press 1998 (12th edition). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim See also S.P.Daiger, L.S. Sullivan, and B.J.F. Rossiter Ret Net http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet disease.htm/. Also E.I. Traboulsi’s, Genetic Diseases of the Eye, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998. And Genetics in Primary Eyecare and Clinical Medicine by M.R. Seashore and R.S.Wappner, Appleton and Lange 1996. M. Ridley’s book Genome published in 2000 by Perennial provides additional information. Ridley estimates that we have 60,000 to 80,000 genes. See also R.M. Henig’s book The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, published by Houghton Mifflin in 2001 which tells about the Father of Genetics. The 3rd edition of F. H. Roy’s book Ocular Syndromes and Systemic Diseases published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002 facilitates differential diagnosis. Additional information is provided in D. Pavan-Langston’s Manual of Ocular Diagnosis and Therapy (5th edition) published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002. M.A. Foote wrote Basic Human Genetics for Medical Writers in the AMWA Journal 2002;17:7-17. A compilation such as this might suggest that one gene = one disease. -

Hyperglycinuria: a Family Report

Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 42. 7 - 12, 1979 7 HYPERGLYCINURIA: A FAMILY REPORT TOMOAKI KATO Department ofPediatrics, Chubu-Rosai Hospital, Nagoya, Japan ABSTRACT A 3-year-old girl with mental retardation and a cleft palate disclosed hyperglycinuria. Serum glycine concentration was within the normal limits and renal clearance of glycine was elevated. Oral loading test of glycine showed that the intestinal absorption of glycine seemed to be nonnal. With intravenous loading of glycine, maximum tubular reabsorption rate (Tm) for glycine could not be obtained. Intravenous infusion of L-proline indicated that the Tm for proline was about half the normal value and that the impaired glycine reabsorption was further depressed. The patient's mother also had a reduced Tm for proline although she did not exhibit distinct hyperglycinuria. It seems likely that the patient and her mother have a heterozygous trait for iminoglycinuria. INTRODUCTION Hyperglycinuria is a rare hereditary disorder characterized by an excessive urinary excretion of glycine. It is caused by an impairment of glycine transport in the renal tubule. The hyperexcretion of glycine was first described in 1957 by de Vries et al. (5) in a family where four members exhibited hyperglycinuria, three of whom had renal stones of calcium oxalate. Hyperglycinuria has been reported at times in association with glucosuria (7), pancreatitis (I), cataract (14), hypophophatemic rickets (4, 12), or mercury intoxication (3). Isolated hyperglycinuria is also seen in heterozygotes with one form of iminoglycinuria (9) where homozygotes excrete excessive amounts of proline, hydroxyproline and glycine in the urine but heterozygotes exhibit a hyperexcretion of glycine only. -

European Conference on Rare Diseases

EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RARE DISEASES Luxembourg 21-22 June 2005 EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RARE DISEASES Copyright 2005 © Eurordis For more information: www.eurordis.org Webcast of the conference and abstracts: www.rare-luxembourg2005.org TABLE OF CONTENT_3 ------------------------------------------------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS A specialised clinic for Rare Diseases : the RD TABLE OF CONTENTS Outpatient’s Clinic (RDOC) in Italy …………… 48 ------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------- 4 / RARE, BUT EXISTING The organisers particularly wish to thank ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS 4.1 No code, no name, no existence …………… 49 ------------------------------------------------- the following persons/organisations/companies 4.2 Why do we need to code rare diseases? … 50 PROGRAMME COMMITTEE for their role : ------------------------------------------------- Members of the Programme Committee ……… 6 5 / RESEARCH AND CARE Conference Programme …………………………… 7 …… HER ROYAL HIGHNESS THE GRAND DUCHESS OF LUXEMBOURG Key features of the conference …………………… 12 5.1 Research for Rare Diseases in the EU 54 • Participants ……………………………………… 12 5.2 Fighting the fragmentation of research …… 55 A multi-disciplinary approach ………………… 55 THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION Funding of the conference ……………………… 14 Transfer of academic research towards • ------------------------------------------------- industrial development ………………………… 60 THE GOVERNEMENT OF LUXEMBOURG Speakers ……………………………………………… 16 Strengthening cooperation between academia -

Screening for Inherited Metabolic Disease in Wales Using Urine-Impregnated Filter Paper

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.50.4.264 on 1 April 1975. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1975, 50, 264. Screening for inherited metabolic disease in Wales using urine-impregnated filter paper D. M. BRADLEY From the Department of Medicine, Welsh National School of Medicine, Heath Park, Cardiff Bradley, D. M. (1975). Archives of Disease in Childhood, 50, 264. Screening for inherited metabolic disease in Wales using urine-impregnated filter paper. Urine specimens from 135 295 infants have been collected on filter paper and tested for 7 abnormal urinary constituents using spot tests and paper chromato- graphy. The method has detected 5 infants with phenylketonuria, 4 with histidinae- mia, 5 with cystinuria, 5 with diabetes mellitus, and one with alcaptonuria. Transient abnormalities such as tyrosyluria, generalized aminoaciduria, cystinuria, and glyco- suria have been noted. 2 phenylketonuric infants failed to excrete a detectable quantity of o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid at the time of testing. The findings show that the detection of this compound in urine is an unreliable method of screening for phenylketonuria. Early detection of phenylketonuria became Method essential when it was found that the severe mental Collection of urine specimens. The recom- retardation associated with this disorder could be mended time of testing is between the 10th and 14th prevented by introducing a low phenylalanine diet day of life. In practice, 53% of all specimens are in the first months of life (Bickel, Gerrard, and collected by the 14th day, rising to 98% by the 28th Hickmans, 1953). The Medical Research Council day (Table I). -

Molecular Patterns Behind Immunological and Metabolic Alterations in Lysinuric Protein Intolerance

MOLECULAR PATTERNS BEHIND IMMUNOLOGICAL AND METABOLIC ALTERATIONS IN LYSINURIC PROTEIN INTOLERANCE Johanna Kurko TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. D osa - tom. 1220 | Medica - Odontologica | Turku 2016 University of Turku Faculty of Medicine Institute of Biomedicine Department of Medical Biochemistry and Genetics Turku Doctoral Programme of Molecular Medicine (TuDMM) Supervised by Adjunct Professor Juha Mykkänen, Ph.D Professor Harri Niinikoski, MD, Ph.D Research Centre of Applied and Department of Paediatrics and Preventive Cardiovascular Medicine Adolescent Medicine University of Turku Turku University Hospital Turku, Finland University of Turku Turku, Finland Reviewed by Adjunct Professor Risto Lapatto, MD, Ph.D Adjunct Professor Outi Monni, Ph.D Department of Paediatrics Research Programs’ Unit and Institute of Helsinki University Hospital Biomedicine University of Helsinki University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland Helsinki, Finland Opponent Adjunct Professor Päivi Saavalainen, Ph.D Research Programs Unit University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-6399-7 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-6400-0 (PDF) ISSN 0355-9483 (PRINT) ISSN 2343-3213 (ONLINE) Painosalama Oy - Turku, Finland 2016 ‘Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.’ Marcus -

Cooperation of Antiporter LAT2/Cd98hc with Uniporter TAT1 for Renal Reabsorption of Neutral Amino Acids

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Cooperation of Antiporter LAT2/CD98hc with Uniporter TAT1 for Renal Reabsorption of Neutral Amino Acids Clara Vilches ,1 Emilia Boiadjieva-Knöpfel,2,3,4 Susanna Bodoy ,5,6 Simone Camargo ,2,3,4 Miguel López de Heredia ,1,7 Esther Prat ,1,7,8 Aida Ormazabal ,7,9 Rafael Artuch ,7,9 Antonio Zorzano ,5,6,10 François Verrey ,2,3,4 Virginia Nunes ,1,7,8 and Manuel Palacín 5,6,7 1Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Genes Disease and Therapy Program, Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica de Bellvitge (IDIBELL), L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain; 2Department of Physiology, 3Zurich Center for Integrative Human Physiology (ZIHP), and 4Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR), Kidney Control of Homeostasis (Kidney.CH), University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; 5Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, Biology Faculty, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; 6Molecular Medicine Unit, Amino acid transporters and disease group, Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST), Barcelona, Spain; 7Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER) – U730, U731, U703, and 10Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM) – CB07/08/0017, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain; 8Genetics Section, Physiological Sciences Department, Health Sciences and Medicine Faculty, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; and 9Clinical Biochemistry Department, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Esplugues de Llobregat, Spain ABSTRACT Background Reabsorption of amino acids (AAs) across the renal proximal tubule is crucial for intracellular and whole organism AA homeostasis. -

Diseases Catalogue

Diseases catalogue AA Disorders of amino acid metabolism OMIM Group of disorders affecting genes that codify proteins involved in the catabolism of amino acids or in the functional maintenance of the different coenzymes. AA Alkaptonuria: homogentisate dioxygenase deficiency 203500 AA Phenylketonuria: phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) 261600 AA Defects of tetrahydrobiopterine (BH 4) metabolism: AA 6-Piruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency (PTS) 261640 AA Dihydropteridine reductase deficiency (DHPR) 261630 AA Pterin-carbinolamine dehydratase 126090 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal recessive) 233910 AA GTP cyclohydrolase I deficiency (GCH1) (autosomal dominant): Segawa syndrome 600225 AA Sepiapterin reductase deficiency (SPR) 182125 AA Defects of sulfur amino acid metabolism: AA N(5,10)-methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency (MTHFR) 236250 AA Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency (CBS) 236200 AA Methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency 250850 AA Methionine synthase deficiency (MTR, cblG) 250940 AA Methionine synthase reductase deficiency; (MTRR, CblE) 236270 AA Sulfite oxidase deficiency 272300 AA Molybdenum cofactor deficiency: combined deficiency of sulfite oxidase and xanthine oxidase 252150 AA S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency 180960 AA Cystathioninuria 219500 AA Hyperhomocysteinemia 603174 AA Defects of gamma-glutathione cycle: glutathione synthetase deficiency (5-oxo-prolinuria) 266130 AA Defects of histidine metabolism: Histidinemia 235800 AA Defects of lysine and -

Renal Tubular Disorders

Renal Tubular Disorders Lisa M. Guay-Woodford nherited renal tubular disorders involve a variety of defects in renal tubular transport processes and their regulation. These disorders Igenerally are transmitted as single gene defects (Mendelian traits), and they provide a unique resource to dissect the complex molecular mechanisms involved in tubular solute transport. An integrated approach using the tools of molecular genetics, molecular biology, and physiology has been applied in the 1990s to identify defects in transporters, channels, receptors, and enzymes involved in epithelial transport. These investigations have added substantial insight into the molecular mechanisms involved in renal solute transport and the molecular pathogenesis of inherited renal tubular disorders. This chapter focuses on the inherited renal tubular disorders, highlights their molecular defects, and discusses models to explain their under- lying pathogenesis. CHAPTER 12 12.2 Tubulointerstitial Disease Overview of Renal Tubular Disorders FIGURE 12-1 OVERVIEW OF RENAL TUBULAR DISORDERS Inherited renal tubular disorders generally INHERITED AS MENDELIAN TRAITS are transmitted as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked dominant, or X-linked recessive traits. For many of Inherited disorder Transmission mode Defective protein these disorders, the identification of the disease-susceptibility gene and its associated Renal glucosuria ?AR, AD Sodium-glucose transporter 2 defective protein product has begun to pro- Glucose-galactose malabsorption syndrome AR Sodium-glucose -

Atypical Gyrate Atrophy of Retina and Iminoglycinuria TAKASHI SAITO

Tohoku J. exp. Med., 1981, 135, 331-332 Short Report Atypical Gyrate Atrophy of the Choroid and Retina and Iminoglycinuria TAKASHI SAITO, SEIJI HAYASAKA,*KAZUYUKI YABATA,* KIYOSHIOMURA, KATSUYOSHI MIZUNO* and KEIYA TADA Departments of Pediatrics and *ophthalmology, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Sendai 980 SAITO, T., HAYASAKA, S., YABATA, K., OMURA, K., MIzuwo, K. and TADA, K. Atypical Gyrate Atrophy of the Choroid and Retina and Iminoglycinuria. Tohoku J. exp. Med., 1981, 135 (3), 331-332 A 44-year-old woman with atypical gyrate atrophy and iminoglycinuria was described. The serum ornithine level and ornithine-ketoacid transaminase (OKT) activity were both normal. Urinary excretion of proline, hydroxyproline and glycine was markedly increased. This finding, together with the existence of gyrate atrophy with hyperornithinemia due to OKT deficiency, suggests that proline deficiency in the chorioretinal tissues may concern the development of gyrate atrophy. - chorioretinal atrophy; hyperornithinemia; iminoglycinuria; proline Gyrate atrophy is a rare, inherited disease of chorioretinal atrophy. The plasma level of ornithine was found to be increased in affected patients (Simell and Takki 1973), and OKT in cultured skin fibroblasts was deficient in these patients. However, the mechanism of the ocular disturbance is still obscure because other patients with a similar degree of hyperornithinemia have no ocular problems (Gatfield et al. 1975) and there are cases of gyrate atrophy without hyperornithinemia (Jaeger et al. 1979). Recently we had a peculiar case which showed fundus changes similar to gyrate atrophy but lacked hyperornithinemia and in which urinary concentrations of imino- acids and glycine were markedly increased. PATIENT AND METHODS The patient was a 44-year-old woman whose parents were first cousins, and had a 5-year history of night blindness. -

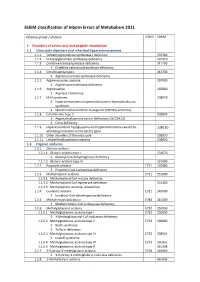

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2. -

Prevalence of Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Neonates

Review Article Clinician’s corner Images in Medicine Experimental Research Case Report Miscellaneous Letter to Editor DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/30035.11515 Original Article Postgraduate Education Prevalence of Inborn Errors of Case Series Metabolism in Neonates Biochemistry Section Biochemistry Short Communication PREETI SHARMA1, PRADEEP KUMAR2, MAYURIKA S TYAGI3, RACHNA SHARMA4, PS DHOT5 ABSTRACT Results: In the present study, 2.9% prevalence (of the total Introduction: Among the most advanced public health promotion 70,590 samples analysed, 2053 cases were found positive) of and disease prevention programs, the newborn screening is of IEM was observed. Of these positive cases, 13% (279 of 2053 paramount importance, seeking timely detection, diagnosis positive cases) cases belonged to eastern zone, 24% (493 of and treatment of genetic disorders which may otherwise lead to 2053 positive cases) were from northern zone, 38% (793 of serious consequences upon the health of newborn. 2053 positive cases) were from southern zone and 23% (488 of Aim: To evaluate the prevalence of Inborn Error of Metabolism 2053 positive cases) were from western zone. Among these, the (IEM) disorders among neonates of various ethnic or racial highest prevalent disorder was found to be G6PD deficiency, groups from east, west, north and south, zones of India through with 1.3% (923 positive of 70,590) cases reported followed newborn screening. by haemoglobinopathies, 0.5% (360 positive of 70,590) and Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional, population based congenital hyperplasia with 0.34% (239 positive of 70,590) prospective study was conducted at PreventiNe Life Care cases of the total newborns, screened. -

Inherited Tubulopathies of the Kidney Insights from Genetics

CJASN ePress. Published on April 6, 2020 as doi: 10.2215/CJN.14481119 Inherited Tubulopathies of the Kidney Insights from Genetics Mallory L. Downie ,1,2 Sergio C. Lopez Garcia ,1,2 Robert Kleta,1,2 and Detlef Bockenhauer 1,2 Abstract The kidney tubules provide homeostasis by maintaining the external milieu that is critical for proper cellular function. Without homeostasis, there would be no heartbeat, no muscle movement, no thought, sensation, or emotion. The task is achieved by an orchestra of proteins, directly or indirectly involved in the tubular transport of 1Department of Renal water and solutes. Inherited tubulopathies are characterized by impaired function of one or more of these specific Medicine, University transport molecules. The clinical consequences can range from isolated alterations in the concentration of specific College London, London, United solutes in blood or urine to serious and life-threatening disorders of homeostasis. In this review, we will focus on Kingdom; and genetic aspects of the tubulopathies and how genetic investigations and kidney physiology have crossfertilized each 2Department of other and facilitated the identification of these disorders and their molecular basis. In turn, clinical investigations of Nephrology, Great genetically defined patients have shaped our understanding of kidney physiology. Ormond Street CJASN ccc–ccc Hospital for Children 16: , 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.14481119 NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom Introduction potentially underlying cause through clinical observa- Homeostasis refers to the maintenance of the “milieu tions. It is clinicians, who, together with genetic and Correspondence: Prof. interieur,” which, as expressed by the physiologist physiologic scientists, have often led the discovery of Detlef Bockenhauer, “ Department of Renal Claude Bernard, is a condition for a free and inde- these transport molecules and their encoding genes Medicine, University pendent existence” (1).