Wiens Et Al. Page: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAT Vertebradosgt CDC CECON USAC 2019

Catálogo de Autoridades Taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala CDC-CECON-USAC 2019 Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Este documento fue elaborado por el Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) del Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala, 2019 Textos y edición: Manolo J. García. Zoólogo CDC Primera edición, 2019 Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala ISBN: 978-9929-570-19-1 Cita sugerida: Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon]. (2019). Catálogo de autoridades taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala (Documento técnico). Guatemala: Centro de Datos para la Conservación [CDC], Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon], Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala [Usac]. Índice 1. Presentación ............................................................................................ 4 2. Directrices generales para uso del CAT .............................................. 5 2.1 El grupo objetivo ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Categorías taxonómicas ......................................................... 5 2.3 Nombre de autoridades .......................................................... 5 2.4 Estatus taxonómico -

Return Rates of Male Hylid Frogs Litoria Genimaculata, L. Nannotis, L

Vol. 11: 183–188, 2010 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online April 16 doi: 10.3354/esr00253 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Return rates of male hylid frogs Litoria genimaculata, L. nannotis, L. rheocola and Nyctimystes dayi after toe-tipping Andrea D. Phillott1, 2,*, Keith R. McDonald1, 3, Lee F. Skerratt1, 2 1Amphibian Disease Ecology Group and 2School of Public Health, Tropical Medicine and Rehabilitation Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia 3Threatened Species Branch, Department of Environment and Resource Management, PO Box 975, Atherton, Queensland 4883, Australia ABSTRACT: Toe-tipping is a commonly used procedure for mark-recapture studies of frogs, although it has been criticised for its potential influence on frog behaviour, site fidelity and mortality. We com- pared 24 h return rates of newly toe-tipped frogs to those previously toe-tipped and found no evi- dence of a stress response reflected by avoidance behaviour for 3 species: Litoria genimaculata, L. rheocola and Nyctimystes dayi. L. nannotis was the only studied species to demonstrate a greater reaction to toe-tipping than handling alone; however, return rates (65%) in the 1 to 3 mo after mark- ing were the highest of any species, showing that the reaction did not endure. The comparatively milder short-term response to toe-tipping in N. dayi (24% return rate) may have been caused by the species’ reduced opportunity for breeding. Intermediate-term return rates were relatively high for 2 species, L. nannotis and L. genimaculata, given their natural history, suggesting there were no major adverse effects of toe-tipping. Longer-term adverse effects could not be ruled out for L. -

Amphibians in Zootaxa: 20 Years Documenting the Global Diversity of Frogs, Salamanders, and Caecilians

Zootaxa 4979 (1): 057–069 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Review ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4979.1.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:972DCE44-4345-42E8-A3BC-9B8FD7F61E88 Amphibians in Zootaxa: 20 years documenting the global diversity of frogs, salamanders, and caecilians MAURICIO RIVERA-CORREA1*+, DIEGO BALDO2*+, FLORENCIA VERA CANDIOTI3, VICTOR GOYANNES DILL ORRICO4, DAVID C. BLACKBURN5, SANTIAGO CASTROVIEJO-FISHER6, KIN ONN CHAN7, PRISCILLA GAMBALE8, DAVID J. GOWER9, EVAN S.H. QUAH10, JODI J. L. ROWLEY11, EVAN TWOMEY12 & MIGUEL VENCES13 1Grupo Herpetológico de Antioquia - GHA and Semillero de Investigación en Biodiversidad - BIO, Universidad de Antioquia, Antioquia, Colombia [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5033-5480 2Laboratorio de Genética Evolutiva, Instituto de Biología Subtropical (CONICET-UNaM), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas Químicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Misiones, Posadas, Misiones, Argentina [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2382-0872 3Unidad Ejecutora Lillo, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas - Fundación Miguel Lillo, 4000 San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina [email protected]; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6133-9951 4Laboratório de Herpetologia Tropical, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Rodovia Jorge Amado Km 16 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4560-4006 5Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, 1659 Museum Road, Gainesville, Florida, 32611, USA [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1810-9886 6Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Av. -

Herramienta Para Evaluar Las Necesidades De Conservación De Anfibio, Panamá, Octubre 2008 Especie En El Rol De Investigación

Herramienta para Evaluar las Necesidades de Conservación de Anfibio, Panamá, Octubre 2008 Page 1 Especie en el Rol de Investigación In Situ 116 especies Una especie que requiere de mayor investigación in situ como parte de las acciones de conservación de esta. Aún falta por conocer al menos una pieza crítica de información. Hábitat Recuperación Estudio Especies Riesgo de extinción Mitigación de amenazas Sobrecolecta protegido de la población filogenético Atelopus varius En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Atelopus zeteki En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Atelopus chiriquiensis En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Oedipina maritima En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Dendrobates arboreus En peligro (EN) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Dendrobates speciosus En peligro (EN) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Craugastor punctariolus En peligro (EN) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Atelopus glyphus En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Bufo fastidiosus En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Bufo peripatetes En peligro crítico (CR) Las amenazas no son reversibles ni serán revertidas a tiempo Herramienta para Evaluar las Necesidades de Conservación de Anfibio, Panamá, Octubre -

Universidade Vila Velha Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Ecologia De Ecossistemas

UNIVERSIDADE VILA VELHA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA DE ECOSSISTEMAS MODELOS DE NICHO ECOLÓGICO E A DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE PHYLLODYTES (ANURA, HYLIDAE): UMA PERSPECTIVA TEMPORAL DE UM GÊNERO POTENCIALMENTE AMEAÇADO DE EXTINÇÃO POR MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS E INTERAÇÕES BIOLÓGICAS MARCIO MAGESKI MARQUES VILA VELHA FEVEREIRO / 2018 UNIVERSIDADE VILA VELHA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA DE ECOSSISTEMAS MODELOS DE NICHO ECOLÓGICO E A DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE PHYLLODYTES (ANURA, HYLIDAE): UMA PERSPECTIVA TEMPORAL DE UM GÊNERO POTENCIALMENTE AMEAÇADO DE EXTINÇÃO POR MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS E INTERAÇÕES BIOLÓGICAS Tese apresentada a Universidade Vila Velha, como pré-requisito do Programa de Pós- Graduação em Ecologia de Ecossistemas, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ecologia. MARCIO MAGESKI MARQUES VILA VELHA FEVEREIRO / 2018 À minha esposa Mariana e meu filho Ângelo pelo apoio incondicional em todos os momentos, principalmente nos de incerteza, muito comuns para quem tenta trilhar novos caminhos. AGRADECIMENTOS Seria impossível cumprir essa etapa tão importante sem a presença do divino Espírito Santo de Deus, de Maria Santíssima dos Anjos e Santos. Obrigado por me fortalecerem, me levantarem e me animarem diante das dificultades, que foram muitas durante esses quatro anos. Agora, servirei a meu Deus em mais uma nova missão. Muito Obrigado. À minha amada esposa Mariana que me compreendeu e sempre esteve comigo me apoiando durante esses quatro anos (na verdade seis, se contar com o mestrado) em momentos de felicidades, tristezas, ansiedade, nervosismo, etc... Esse período nos serviu para demonstrar o quanto é forte nosso abençoado amor. Sem você isso não seria real. Te amo e muito obrigado. Ao meu amado filho, Ângelo Miguel, que sempre me recebia com um iluminado sorriso e um beijinho a cada vez que eu chegava em casa depois de um dia de trabalho. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) from the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas

Chapter 9 Carnivora (Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) From the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas MARGARET SKEELS STEVENS1 AND JAMES BOWIE STEVENS2 ABSTRACT The Screw Bean Local Fauna is the earliest Hemphillian fauna of the southwestern United States. The fossil remains occur in all parts of the informal Banta Shut-in formation, nowhere very fossiliferous. The formation is informally subdivided on the basis of stepwise ®ning and slowing deposition into Lower (least fossiliferous), Middle, and Red clay members, succeeded by the valley-®lling, Bench member (most fossiliferous). Identi®ed Carnivora include: cf. Pseudaelurus sp. and cf. Nimravides catocopis, medium and large extinct cats; Epicyon haydeni, large borophagine dog; Vulpes sp., small fox; cf. Eucyon sp., extinct primitive canine; Buisnictis chisoensis, n. sp., extinct skunk; and Martes sp., marten. B. chisoensis may be allied with Spilogale on the basis of mastoid specialization. Some of the Screw Bean taxa are late survivors of the Clarendonian Chronofauna, which extended through most or all of the early Hemphillian. The early early Hemphillian, late Miocene age attributed to the fauna is based on the Screw Bean assemblage postdating or- eodont and predating North American edentate occurrences, on lack of de®ning Hemphillian taxa, and on stage of evolution. INTRODUCTION southwestern North America, and ®ll a pa- leobiogeographic gap. In Trans-Pecos Texas NAMING AND IMPORTANCE OF THE SCREW and adjacent Chihuahua and Coahuila, Mex- BEAN LOCAL FAUNA: The name ``Screw Bean ico, they provide an age determination for Local Fauna,'' Banta Shut-in formation, postvolcanic (,18±20 Ma; Henry et al., Trans-Pecos Texas (®g. -

For Review Only

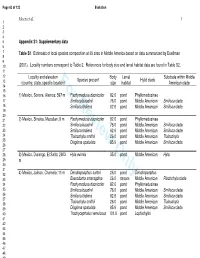

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

The Most Frog-Diverse Place in Middle America, with Notes on The

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(2) [Special Section]: 304–322 (e215). The most frog-diverse place in Middle America, with notes on the conservation status of eight threatened species of amphibians 1,2,*José Andrés Salazar-Zúñiga, 1,2,3Wagner Chaves-Acuña, 2Gerardo Chaves, 1Alejandro Acuña, 1,2Juan Ignacio Abarca-Odio, 1,4Javier Lobon-Rovira, 1,2Edwin Gómez-Méndez, 1,2Ana Cecilia Gutiérrez-Vannucchi, and 2Federico Bolaños 1Veragua Foundation for Rainforest Research, Limón, COSTA RICA 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, 11501-2060 San José, COSTA RICA 3División Herpetología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’-CONICET, C1405DJR, Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA 4CIBIO Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, InBIO, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Rua Padre Armando Quintas 7, 4485-661 Vairão, Vila do Conde, PORTUGAL Abstract.—Regarding amphibians, Costa Rica exhibits the greatest species richness per unit area in Middle America, with a total of 215 species reported to date. However, this number is likely an underestimate due to the presence of many unexplored areas that are diffcult to access. Between 2012 and 2017, a monitoring survey of amphibians was conducted in the Central Caribbean of Costa Rica, on the northern edge of the Matama mountains in the Talamanca mountain range, to study the distribution patterns and natural history of species across this region, particularly those considered as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The results show the highest amphibian species richness among Middle America lowland evergreen forests, with a notable anuran representation of 64 species. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Instituto De Biociências – Rio Claro Programa De Pós

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” unesp INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS – RIO CLARO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS (ZOOLOGIA) ANFÍBIOS DA SERRA DO MAR: DIVERSIDADE E BIOGEOGRAFIA LEO RAMOS MALAGOLI Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências do Câmpus de Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de doutor em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia). Agosto - 2018 Leo Ramos Malagoli ANFÍBIOS DA SERRA DO MAR: DIVERSIDADE E BIOGEOGRAFIA Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências do Câmpus de Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de doutor em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia). Orientador: Prof. Dr. Célio Fernando Baptista Haddad Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Ricardo Jannini Sawaya Rio Claro 2018 574.9 Malagoli, Leo Ramos M236a Anfíbios da Serra do Mar : diversidade e biogeografia / Leo Ramos Malagoli. - Rio Claro, 2018 207 f. : il., figs., gráfs., tabs., fots., mapas Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências de Rio Claro Orientador: Célio Fernando Baptista Haddad Coorientador: Ricardo Jannini Sawaya 1. Biogeografia. 2. Anuros. 3. Conservação. 4. Diversidade funcional. 5. Elementos bióticos. 6. Mata Atlântica. 7. Regionalização. I. Título. Ficha Catalográfica elaborada pela STATI - Biblioteca da UNESP Campus de Rio Claro/SP - Ana Paula Santulo C. de Medeiros / CRB 8/7336 “To do science is to search for repeated patterns, not simply to accumulate facts, and to do the science of geographical ecology is to search for patterns of plant and animal life that can be put on a map. The person best equipped to do this is the naturalist.” Geographical Ecology. Patterns in the Distribution of Species Robert H. -

Hylidae, Anura) and Description of Ocellated Treefrog Itapotihyla Langsdorffii Vocalizations

Current knowledge on bioacoustics of the subfamily Lophyohylinae (Hylidae, Anura) and description of Ocellated treefrog Itapotihyla langsdorffii vocalizations Lucas Rodriguez Forti1, Roseli Maria Foratto1, Rafael Márquez2, Vânia Rosa Pereira3 and Luís Felipe Toledo1 1 Laboratório Multiusuário de Bioacústica (LMBio) e Laboratório de História Natural de Anfíbios Brasileiros (LaHNAB), Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 2 Fonoteca Zoológica, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Madrid, Spain 3 Centro de Pesquisas Meteorológicas e Climáticas Aplicadas à Agricultura (CEPAGRI), Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil ABSTRACT Background. Anuran vocalizations, such as advertisement and release calls, are informative for taxonomy because species recognition can be based on those signals. Thus, a proper acoustic description of the calls may support taxonomic decisions and may contribute to knowledge about amphibian phylogeny. Methods. Here we present a perspective on advertisement call descriptions of the frog subfamily Lophyohylinae, through a literature review and a spatial analysis presenting bioacoustic coldspots (sites with high diversity of species lacking advertisement call descriptions) for this taxonomic group. Additionally, we describe the advertisement and release calls of the still poorly known treefrog, Itapotihyla langsdorffii. We analyzed recordings of six males using the software Raven Pro 1.4 and calculated the coefficient Submitted 24 February 2018 of variation for classifying static and dynamic acoustic properties. Accepted 30 April 2018 Results and Discussion. We found that more than half of the species within the Published 31 May 2018 subfamily do not have their vocalizations described yet. Most of these species are Corresponding author distributed in the western and northern Amazon, where recording sampling effort Lucas Rodriguez Forti, should be strengthened in order to fill these gaps.