A Constructive Critique of India's Fast-Track Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIJL Bulletin-7-1981-Eng

CIJL BULLETIN N°7 CONTENTS CASE REPORTS India 1 Paraguay 19 Pakistan 8 Guatemala 24 Malta 13 El Salvador 25 Haiti 17 ACTIVITIES OF LAWYERS ASSOCIATIONS Geneva Meeting on the Independence of Lawyers 27 The Inter-American Bar Association 32 Declaration of All-India Lawyers Conference 35 ARTICLE The Difficult Relationship of the Judiciary with the Executive and Legislative Branches in France by Louis Joinet 37 APPENDIX CIJL Communication to Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Concerning Attacks on Judges and Lawyers in Guatemala 45 CENTRE FOR THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS April 1981 Editor: Daniel O'Donnell THE CENTRE FOR THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS (CIJL) The Centre for the Independence of Judges and Lawyers was created by the In ternational Commission of Jurists in 1978 to promote the independence of the judiciary and the legal profession. It is supported by contributions from lawyers' organisations and private foundations. The Danish, Netherlands, Norwegian and Swedish bar associations, the Netherlands Association of Jurists and the Association of Arab Jurists have all made contributions of $1,000 or more for the current year, which is greatly appreciated. The work of the Centre during its first two years has been supported by generous grants from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, but its future will be dependent upon increased funding from the legal profession. A grant from the Ford Foundation has helped to meet the cost of publishing the Bulletin in english, french and spanish. There remains a substantial deficit to be met. We hope that bar associations and other lawyers' organisations concerned with the fate of their colleagues around the world will decide to provide the financial support essential to the survival of the Centre. -

Public Domain Information Resources

CHAPTER 4 PUBLIC DOMAIN INFORMATION RESOURCES Chap. 4—Public Domain Information Resources UNESCO Recommendation on Promotion and use of Multilingualism and Universal Access to Cyberspace provides the following definition: “Public domain information refers to publicly accessible information, the use of which does not infringe any legal right, or any obligation of confidentiality. It thus refers on the one hand to the realm of all works or objects of related rights, which can be exploited by everybody without any authorization, for instance because protection is not granted under national or international law, or because of the expiration of the term of protection. It refers on the other hand to public data and official information produced and voluntarily made available by governments or international organizations.1” 4.1 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Parliamentary Debate is a recording of conversation of parliamentarians of a nation to discuss over agenda, proposed legislations and other developmental programmes. It is treated as primary legal literature and very useful for legal research scholars. While tracing the origin of legislation, it is quite useful to refer parliamentary debates of parliamentarians over the bill or proposed legislations. ONLINE ACCESS OF PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Parliament of India Debates http://164.100.47.132/LssNew/Debates/debates.aspx United States of America Senates Debates http://www.house.gov/ 1. Uhlir, Paul F, Policy Guidelines for the Development and Promotion of Governmental Public Domain Information, Paris: UNESCO, 2004. 37 38 CHAP. 4—PUBLIC DOMAIN INFORMATION RESOURCES UK House of Commons & House of Lords Debates (Hansard) http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/pahansard.htm 4.2 LEGISLATION A Legislation or Statute is a formal act of the Legislature in written form. -

(CIVIL) NO. 1232 of 2017 Swapnil Tripathi ….. Peti

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1232 OF 2017 Swapnil Tripathi ….. Petitioner(s) :Versus: Supreme Court of India ....Respondent(s) WITH WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 66 OF 2018 Indira Jaising …..Petitioner(s) :Versus: Secretary General & Ors. ....Respondent(s) AND WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 861 OF 2018 Mathews J. Nedumpara & Ors. ….. Petitioner(s) :Versus: Supreme Court of India & Ors. …..Respondent(s) AND WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 892 OF 2018 Centre for Accountability and Systemic Change & Ors. ….. Petitioner(s) :Versus: Secretary General & Ors. …..Respondent(s) 2 J U D G M E N T A.M. Khanwilkar, J. 1. The petitioners and interventionists, claiming to be public spirited persons, have sought a declaration that Supreme Court case proceedings of “constitutional importance having an impact on the public at large or a large number of people” should be live streamed in a manner that is easily accessible for public viewing. Further direction is sought to frame guidelines to enable the determination of exceptional cases that qualify for live streaming and to place those guidelines before the Full Court of this Court. To buttress these prayers, reliance has been placed on the dictum of a nine-Judge Bench of this Court in Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar and Ors. Vs. State of Maharashtra and Ors.,1 which has had an occasion to inter alia consider the arguments of journalists that they had a fundamental right to carry on their occupation under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution; that they also had a right to attend the proceedings in court under Article 19(1)(d); and that their right 1 (1966) 3 SCR 744 3 to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) included their right to publish a faithful report of the proceedings which they had witnessed and heard in Court as journalists. -

(CIVIL) NO. 558 of 2012 Kalpana Mehta and Ot

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 558 OF 2012 Kalpana Mehta and others …Petitioner(s) Versus Union of India and others …Respondent(s) WITH WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 921 OF 2013 J U D G M E N T Dipak Misra, CJI. [For himself and A.M. Khanwilkar, J.] I N D E X S. No. Heading Page No. A. Introduction 3 B. The factual background 4 B.1 The Reference 6 C. Contentions of the petitioners 8 D. Contentions of the respondents 12 E. Supremacy of the Constitution 14 F. Constitutional limitations upon the 17 legislature 2 G. Doctrine of separation of powers 21 H. Power of judicial review 28 I. Interpretation of the Constitution – The 34 nature of duty cast upon this Court I.1 Interpretation of fundamental rights 40 I.2 Interpretation of other 42 constitutional provisions J. A perspective on the role of Parliamentary 48 Committees K. International position of Parliamentary 54 Committees K.1 Parliamentary Committees in 54 England K.2 Parliamentary Committees in United 55 States of America K.3 Parliamentary Committees in 58 Canada K.4 Parliamentary Committees in 59 Australia L. Parliamentary Committees in India 60 L.1 Rules of Procedure and Conduct of 65 Business in Lok Sabha M. Parliamentary privilege 71 M.1 Parliamentary privilege under the 72 Indian Constitution M.2 Judicial review of parliamentary 81 proceedings and its privilege N. Reliance on parliamentary proceedings as 91 external aids O. Section 57(4) of the Indian Evidence Act 101 P. -

Judicial Review: a Study in Reference to Contemporary Judicial System in India

[Tripathi *, Vol.4 (Iss.5): May, 2016] ISSN- 2350-0530(O) ISSN- 2394-3629(P) Impact Factor: 2.532 (I2OR) DOI: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i5.2016.2673 Social JUDICIAL REVIEW: A STUDY IN REFERENCE TO CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL SYSTEM IN INDIA Dr. Rahul Tripathi *1 *1 Assistant Professor, Amity University, Jaipur (Rajasthan), INDIA ABSTRACT Judicial review is the process by which the Courts determine whether or not an administrative decision-maker has acted within the power conferred upon him or her by Parliament. That places the question of statutory construction at the heart of the enquiry. The Supreme Court enjoys a position which entrusts it with the power of reviewing the legislative enactments both of Parliament and the State Legislatures. This grants the court a powerful instrument of judicial review under the constitution. Research reveals that the Supreme Court has taken in hand the task of rewriting the Constitution, which is an important aspect in present scenario. Keywords: Judicial Review, Activism, Writ, Article. Cite This Article: Dr. Rahul Tripathi, “JUDICIAL REVIEW: A STUDY IN REFERENCE TO CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL SYSTEM IN INDIA” International Journal of Research – Granthaalayah, Vol. 4, No. 5 (2016): 51-55. 1. INTRODUCTION "EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW"-These words reflect the ultimate responsibility of the Judiciary of India. In India, the Supreme Court is the highest tribunal in the Nation for all cases and controversies arising under the Constitution or the laws. As the final arbiter of the law, the Court is charged with ensuring the of Indian people the promise of equal justice under law and, Judicial Review and Judicial Activism: Administrative Perspective & Writs. -

Judiciary of India

Judiciary of India There are various levels of judiciary in India – different types of courts, each with varying powers depending on the tier and jurisdiction bestowed upon them. They form a strict hierarchy of importance, in line with the order of the courts in which they sit, with the Supreme Court of India at the top, followed by High Courts of respective states with district judges sitting in District Courts and Magistrates of Second Class and Civil Judge (Junior Division) at the bottom. Courts hear criminal and civil cases, including disputes between individuals and the government. The Indian judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches of government according to the Constitution. Courts- Supreme Court of India On 26 January 1950, the day India’s constitution came into force, the Supreme Court of India was formed in Delhi. The original Constitution of 1950 envisaged a Supreme Court with a Chief Justice and 7 puisne Judges – leaving it to Parliament to increase this number. In the early years, all the Judges of the Supreme Court sit together to hear the cases presented before them. As the work of the Court increased and arrears of cases began to accumulate, Parliament increased the number of Judges from 8 in 1950 to 11 in 1956, 14 in 1960, 18 in 1978 and 26 in 1986. As the number of the Judges has increased, they sit in smaller Benches of two and three – coming together in larger Benches of 5 and more only when required to do so or to settle a difference of opinion or controversy. -

Mla Ratings 2019

A comprehensive & objective rating of the Elected Representatives’ performance MLA RATINGS 2019 MUMBAI REPORT CARD Founded in 1998, the PRAJA Foundation is a non-partisan voluntary organisation which empowers the citizen to participate in governance by providing knowledge and enlisting people’s participation. PRAJA aims to provide ways in which the citizen can get politically active and involved beyond the ballot box, thus promoting transparency and accountability. Concerned about the lack of awareness and apathy of the local government among citizens, and hence the disinterest in its functioning, PRAJA seeks change. PRAJA strives to create awareness about the elected representatives and their constituencies. It aims to encourage the citizen to raise his/ her voice and influence the policy and working of the elected representative. This will eventually lead to efforts being directed by the elected representatives towards the specified causes of public interest. The PRAJA Foundation also strives to revive the waning spirit of Mumbai City, and increase the interaction between the citizens and the government. To facilitate this, PRAJA has created www.praja.org, a website where the citizen can not only discuss the issues that their constituencies face, but can also get in touch with their elected representatives directly. The website has been equipped with information such as: the issues faced by the ward, the elected representatives, the responses received and a discussion board, thus allowing an informed interaction between the citizens of the area. PRAJA’s goals are: empowering the citizens, elected representatives & government with facts and creating instruments of change to improve the quality of life of the citizens of India. -

Press Release White Pearls Hotels and Investments Private Limited

Press Release White Pearls Hotels and Investments Private Limited April 03, 2018 Rating Facilities Amount (Rs. crore) Rating1 Rating Action CARE B+; Stable Long term Bank Facilities 15.00 Reaffirmed (Single B Plus; Outlook: Stable) 15.00 Total Facilities (Rupees Fifteen crore only) Details of instruments/facilities in Annexure I Detailed Rationale & Key Rating Drivers The rating assigned to the bank facilities of White Pearls Hotels and Investments Private Limited (WHIPL) continues to be constrained by its modest scale of operations, leveraged capital structure and weak debt protection metrics. The rating further continues to be constrained by investment in loss-making subsidiaries and its presence in the highly competitive and fragmented industry with demand linkage from the cyclical real estate sector. The rating continues to derive strength from experience and resourcefulness of the promoters in hospitality and real estate leasing business, WHIPL’s long track record and location advantage of its hotel and real estate properties and healthy profit margins. Going forward, the company’s ability to timely receive the lease rentals and maintain occupancy in both hospitality and lease rental business amidst increasing competition along with any further investment in the loss making subsidiaries are the key rating sensitivities. Detailed description of the key rating drivers Key Rating Weaknesses Modest scale of operations: The scale of operations WHIPL stood modest as indicated by its total operating income of Rs.12.58 crore and gross cash accruals of Rs.3.07 crore. Further the net-worth also stood at Rs.17.13 crore as on March 31, 2017. This thereby has limited financial flexibility of the company. -

Conference on Court Governance Verbatim

CONFERENCE ON COURT GOVERNANCE VERBATIM PROGRAMME REPORT – P 979 Submitted by Sanmit Seth, Law Associate & Anmol Jain, Law Intern National Judicial Academy 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SESSION 1 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 SESSION 2 ......................................................................................................................................... 40 SESSION 3 ......................................................................................................................................... 66 SESSION 4 ......................................................................................................................................... 89 SESSION 5 ....................................................................................................................................... 120 SESSION 6 ....................................................................................................................................... 142 SESSION 7 ....................................................................................................................................... 166 SESSION 8 ....................................................................................................................................... 200 SESSION 9 AND 10 .......................................................................................................................... 227 SESSION 11 .................................................................................................................................... -

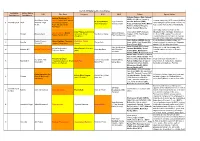

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

Monthly Emagazine "Advocacy"

ADVOCACY TMV's Lokmanya Tilak Law College's MONTHLY eMAGAZINE Volume I Issue 3 (May 2021) CONTENTS 1. Indian Judiciary – Evolution. 2. India’s “Justice League”- Torchbearers of Justice for Modern India. 3. Virtual Courtroom System- Future of India’s Judicial System. 4. Medical Jurisprudence- A Connection between Law and Medicine. 5. Hospital Fires - Laws for Prevention, Protection and Fire Fighting Installations (As per the National Building Code, 2005). Student Editor Faculty In-Charge Purvanshi Prajapat Asst. Prof.Vidhya Shetty BA.LL.B 4th Year Articles invited for the next issue, interested candidates can mail your articles on [email protected] ADVOCACY Volume 1 issue 3 (MAY 2021) FOREWORD World Press Freedom Day I am delighted to share the third issue of our eMagazine known as "ADVOCACY" with all of you, which will provide insights on various legal aspects. In December 1993 the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed that every year worldwide 3rd May would be celebrated as World Press Freedom Day also known as World Press Day. This was done on the recommendations of the UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cul- tural Organization) General Conference and to mark the anniversary of Windhoek Declaration held in Windhoek, Namibia, from 29 April to 3 May 1991. Every year to mark the significance of this day a Global Conference is organised by UNESCO since 1993 in order to provide an opportunity to the journalists, national authorities, academicians and the general public to discuss about the various changing and challenging aspects of “Freedom of Press.” Also to suggest safety measures to protect the life of the journalists and to work together to identify solutions to the emerging problems or challenges in this arena. -

Indian Administration

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Basic of Indian Administration Subject:BASIC OF INDIAN ADMINISTRATION Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Historical Context Administrative System at the Advent of British Rule, British Administration: 1757-1858, Reforms in British Administration: 1858 to 1919, Administrative System under 1935 Act, Continuity and Change in Indian Administration: Post 1947 Central Administration Constitutional Framework, Central Secretariat: Organization and Functions, Prime Minister's Office and Cabinet Secretariat, Union Public Service Commission/Selection Commission, Planning Process, All India and Central Services State Administration Constitutional Profile of State Administration, State Secretariat: Organization and Functions, Patterns of Relationship Between the Secretariat and Directorates, State Services and Public Service Commission Field and Local Administration Field Administration, District Collector, Police Administration, Municipal Administration, Panchayati Raj and Local Government Citizen and Administration Socio-Cultural Factors and Administration, Redressal of Public Grievances, Administrative Tribunals Judicial Administration Emerging Issues Centre-State Administrative Relationship, Decentralization Debate Pressure Groups, Relationship Between Political and Permanent Executives, Pressure Groups, Generalists and Specialists, Administrative Reforms Suggested Readings: