The Four Flights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of David Ray Griffin's 9/11 Fake Calls Theory by Erik

Critique of David Ray Griffin’s 9/11 Fake Calls Theory by Erik ... http://911blogger.com/news/2011-02-10/critique-david-ray-griffi... Search Paying Attention to 9/11 Related News news blogs (0 new) comments (10) tags search about us features contact us site rules faq help news feb 2011 critique of david ray griffin’s headlines 9/11 fake calls theory by erik larson Critique of David Ray Griffin’s New video released: "Inside 9/11 - 7 facts" 9/11 Fake Calls Theory by Erik Dear 9/11 First Responders Larson Bipartisan Congressional Bill Would Authorize submitted by loose nuke on thu, 02/10/2011 - 10:55pm the Use of Propaganda On Americans Living Inside America Dennis Kucinich: 911 Truth and Reconciliation Beginning with his book New Pearl Harbor (2004) David Ray Griffin raised questions DOJ Confirms Previously-Denied File Said to concerning the veracity of reports of phone Implicate US Officials in Nuclear Espionage by calls from the 9/11 hijacked airliners, Erik Larson specifically, Ted Olson’s account. Since at least 2006, he has promoted a theory that the 9/11 9/11 as sequel to Iran-Contra: Armitage, Carlucci plane passenger phone calls were faked, and and friends has speculated this was done with ‘voice- Secret Service Failures on 9/11: A Call for morphing’ technology. He’s done this in many Transparency different articles, in books, in speaking appearances, in interviews on radio 'Real-World or Exercise': Did the U.S. Military and television, and in a debate with Matt Taibbi Mistake the 9/11 Attacks for a Training Scenario? of Rolling Stone magazine. -

Impact, Action, Remembrance Table of Contents

9/11 in Massachusetts: Impact, Action, Remembrance Table of Contents Page 02 - Voiceover Script 1. Intro – Start 00:00 – Duration 1:00 2. The Attacks – Start 01:00 – Duration 2:43 3. Local Heroes – Start 03:43 – Duration 1:07 4. Rescue Efforts – Start 05:50 – Duration 1:11 5. The Aftermath – Start 07:01 – Duration 2:07 6. Assistance for the Survivors – Start 09:08 – Duration 1:52 7. Local Memorials – Start 11:00 – Duration 2:50 8. Massachusetts 9/11 Victims – Start 13:50 – Duration 8:08 Page 06 - Massachusetts 9/11 Victims List Page 09 - Works Cited Page Page 11 - Proposed Questions by Section Page 12 - Homework Ideas Page 13 – Source Materials 9/11 in Massachusetts: Impact, Action, Remembrance Page 2 of 17 Voiceover script Intro – Start 00:00 – Duration 1:00 9/11 was the single deadliest terrorist attack in human history, and it took place right here on US soil. Nearly 3,000 people, representing 90 different countries, lost their lives that day. These victims were business men and women, vacation-goers, and loved ones heading from the east coast to California to visit friends and family. What started out as a beautiful Fall day on the east coast in the United States with thousands of commuters heading to work and going about their everyday lives, ended in tragedy and sorrow, leaving behind a permanent scar that would change all our lives forever. The events of 9/11 affected our entire country on a grand scale both economically and culturally. But Massachusetts was a part of this day, from the attacks to the impact. -

Mary Campany LIS 601/Irvin 1 Bibliography

Mary Campany LIS 601/Irvin Bibliography Research Plan Terrorism in the Middle East: What’s going on? Mary Campany December 16, 2015 LIS 601/ Fall 2015 Dr. Vanessa Irvin 1 Mary Campany LIS 601/Irvin Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………3 Audience ...………………………………………………………………………….3 Citation Style……………………………………….……………………………......3 Search Strategies………………………………………………………………………….…4 Search Terms………………………………………………………………………..4 Call Numbers (Dewey Decimal System and Library of Congress)…………4 Library of Congress Subject Headings……………………………………...4 Search Terms, Boolean expressions, and Natural Language……………......4 Search Process ………………………………………………………………………………5 OPACS………………………………………………………………………………5 Databases and Indexes………………………………………………………………6 Web Resources…………………………………………………………………… .11 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….13 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………..15 Appendix I – Annotated Bibliography……………………………………………………..17 Appendix II – Search Terms Relevancy Chart…………………………………………….20 2 Mary Campany LIS 601/Irvin Introduction On November 13th, at nearly 9:30pm, the streets of Paris echoed with gunshots and screams. Gunmen were killing people at Parisian cafes, restaurants, and a concert. Over 130 people died, with many more injured (Steafel). In the aftermath, one can’t help but wonder: why? When ISIS, a Middle-Eastern terrorist group took credit for the massacre, many adults no doubt remember an equally horrifying act of terrorism, 9/11. This bibliography plan is about terrorism, with the sub-topics “ISIS and the Paris Attacks” and “Al-Quaeda and 9/11”. These two sub-topic are major acts of terrorism, and thus go hand-in-hand with the main topic. They are also related to each other, since ISIS is a group that splintered off from Al-Quaeda (Laub). Most of the databases explored in this bibliography plan are general and fact-based, rather than analytical. This allows for researchers to get an idea of what is going on in the world so that they can form their own opinions on this issue and the responses to it. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Extensions of Remarks E1673 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 22, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1673 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A PROCLAMATION THANKING PRI- COMMENDING CHARLES A. COHEN, Mr. Speaker, I ask that you and my col- VATE FIRST CLASS RYAN A. AN OUTSTANDING CITIZEN OF leagues in the People’s House join in com- MARTIN FOR HIS SERVICE TO INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA AND RE- mending Charles Cohen for his life of service, OUR COUNTRY CIPIENT OF THE NEW JERU- civic stewardship and commitment to Indian- SALEM AWARD apolis and Israel Bonds. He has exhibited outstanding leadership HON. ROBERT W. NEY HON. JULIA CARSON qualities that deserve high praise. OF OHIO OF INDIANA f IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PAYING TRIBUTE TO FBI DEPUTY DIRECTOR BRUCE GEBHARDT Wednesday, September 22, 2004 Wednesday, September 22, 2004 Ms. CARSON of Indiana. Mr. Speaker, it is Mr. NEY. Mr. Speaker, we hereby offer our with profound pleasure and privilege that I rise HON. MIKE ROGERS heartfelt condolences to the family, friends, to commend to the nation, Charles A. (Chuck) OF ALABAMA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES and community of Private First Class Ryan A. Cohen, an outstanding American and citizen Martin upon the death of this outstanding sol- of Indianapolis, Indiana. Wednesday, September 22, 2004 dier; and Mr. Cohen will be honored October 17, with Mr. ROGERS of Michigan. Mr. Speaker, I Whereas, Private First Class Ryan A. Martin the New Jerusalem Award at the Indiana- rise today to pay tribute to Deputy Director was a member of the 216th Engineer Battalion Israel Dinner of State. Chuck is an active com- Bruce Gebhardt for his 30 years of distin- of the Army National Guard serving his great munity leader, a prominent attorney and a guished service to the Federal Bureau of In- nation in the country of Iraq. -

The Spectral Voice and 9/11

SILENCIO: THE SPECTRAL VOICE AND 9/11 Lloyd Isaac Vayo A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Eileen C. Cherry Chandler Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Don McQuarie © 2010 Lloyd Isaac Vayo All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor “Silencio: The Spectral Voice and 9/11” intervenes in predominantly visual discourses of 9/11 to assert the essential nature of sound, particularly the recorded voices of the hijackers, to narratives of the event. The dissertation traces a personal journey through a selection of objects in an effort to seek a truth of the event. This truth challenges accepted narrativity, in which the U.S. is an innocent victim and the hijackers are pure evil, with extra-accepted narrativity, where the additional import of the hijacker’s voices expand and complicate existing accounts. In the first section, a trajectory is drawn from the visual to the aural, from the whole to the fragmentary, and from the professional to the amateur. The section starts with films focused on United Airlines Flight 93, The Flight That Fought Back, Flight 93, and United 93, continuing to a broader documentary about 9/11 and its context, National Geographic: Inside 9/11, and concluding with a look at two YouTube shorts portraying carjackings, “The Long Afternoon” and “Demon Ride.” Though the films and the documentary attempt to reattach the acousmatic hijacker voice to a visual referent as a means of stabilizing its meaning, that voice is not so easily fixed, and instead gains force with each iteration, exceeding the event and coming from the past to inhabit everyday scenarios like the carjackings. -

FALL and RISE: the Story of 9/11

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kate D’Esmond (212) 207-7362 / [email protected] “The horror and heroism of 9/11 are brought to life in this panoramic history. ... The result is a superb, harrowing retelling of this most dramatic of stories.” — Publishers Weekly, starred review “A meticulously delineated, detailed, graphic history of the events of 9/11 in New York City, at the Pentagon, and in Pennsylvania. ... Despite the story’s sprawling cast, which could have sabotaged a book by a less-skilled author, Zuckoff ably handles all of the complexities. ... [A]s contemporary history, Fall and Rise is a clear and moving success.” — Kirkus Reviews, starred review FALL AND RISE: The Story of 9/11 by Mitchell Zuckoff #1 New York Times bestselling author Harper • on sale April 30, 2019 On the morning of September 11, 2001, bestselling author and journalist Mitchell Zuckoff was on book leave from the Boston Globe when his editor called: airplanes had struck the Twin Towers of New York’s World Trade Center in an apparent terrorist attack. Both planes that hit the towers had taken off from Boston’s Logan Airport. Zuckoff rushed to the newsroom. He wrote the lead story that appeared on Page One of the Globe the next day (see below), and for months after, Zuckoff wrote about the attacks, the perpetrators, the victims, and their families. So began an abiding commitment to the true story of that day, culminating here in FALL AND RISE: The Story of 9/11 (Harper; on sale April 30, 2019; $29.99). After years of meticulous reporting, Zuckoff, the bestselling author of 13 Hours, has written the first comprehensive nonfiction narrative of that terrible day. -

Director's Report

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO COMMISSION ON THE ENVIRONMENT DIRECTOR’S REPORT March 26, 2019 ------------------------------- This report covers San Francisco Department of the Environment updates for the period of January 1, 2019 – February 28, 2019. Glossary of acronyms at bottom of report. Residential Programs - TOXICS REDUCTION/OUTREACH: Conducted a citywide survey of San Francisco’s used motor oil do-it-yourselfer community to help better understand our target audience. The survey will be used to assist the Department to direct future outreach campaigns. - COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS: While, this is a slower season for events, Department staff participated in 7 community engagement activities including tabling, presenting and engaging with the public at Fairs and Neighborhood Festivals. Highlights include: o ENVIRONMENT NOW/SCHOOL ED/ENERGY: Tabled at the Neighborhood Empowerment Network awards ceremony o ENVIRONMENT NOW/SCHOOL ED/ENERGY: Launched the new 0-80-100-Roots framework for tabling at the California Academy of Sciences Family Night. Reached 350 people. o SCHOOL ED: Tabled at the SF Citywide Summer Resource Fair for parents seeking summer programs for their children. Reached 250 people. o SCHOOL ED: Tabled at Betty Ong Rec Center for the Summer Resource Fair. Reached 15 people. o ENVIRONMENT NOW/EDUCATION/ TOXICS REDUCTION: Staff members tabled at the Martin Luther King Jr. Health and Wellness Fair at the Yerba Buena Center on January 21,2019. - ZERO WASTE: Completed rollout of smaller trash and larger recycling bins to 80% of city, with 113,592 bins exchanged. Replaced stickers with Outreach on 204,460 residential and 141,243 apartment and commercial bins. -

1.1 Inside the Four Flights

SUBJECT TO CLASSIFICATION RE'VIEW CHAPTER ONE "WE HAVE SOME PLANES" Tuesday, September 11, 2001, dawned temperate and nearly cloudless in the eastern United States. Millions of men and women readied themselves for work. Some made their way to the Twin Towers, the signature structures of the World Trade Center complex in New York City. Others went to the Pentagon, the world's largest office building. Across the Potomac river, the United States Congress was back in session. In Sarasota, Florida, President George W. Bush went for an early morning run. For those heading to an airport, weather conditions could not have been better for a safe and pleasant journey. Among the travelers were Mohamed Atta and Abdul Aziz al Omari, who arrived at the airport in Portland, Maine. 1.1 Inside the Four Flights Boarding the Flights Boston: American 11 and Ullited 175. Atta and a1 Omari boarded a 6:00a.m. flight from Portland to Boston's Logan International Airport.1 When he checked in for his flight to Boston, Atta was selected by a computerized prescreening system known as CAPPS created to identify passengers who should be subject to special security measures. Under security directives in place at the time, the only consequence of Atta's selection by CAPPS was that his checked bags were held off the plane until it was confirmed that he had boarded the aircraft. This did not hinder 2 Atta's plans. · Atta and Omari arrived in Boston at 6:45. Seven minutes later, Atta apparently took a call from Marwan al Shehhi, a longtime colleague who was at another terminal at Logan airport. -

The 9/11 Commission Report

Final1-4.4pp 7/17/04 9:12 AM Page 1 1 “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” Tuesday, September 11, 2001, dawned temperate and nearly cloudless in the eastern United States. Millions of men and women readied themselves for work. Some made their way to the Twin Towers, the signature structures of the World Trade Center complex in New York City.Others went to Arlington,Vir- ginia, to the Pentagon.Across the Potomac River, the United States Congress was back in session. At the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, people began to line up for a White House tour. In Sarasota, Florida, President George W.Bush went for an early morning run. For those heading to an airport, weather conditions could not have been better for a safe and pleasant journey.Among the travelers were Mohamed Atta and Abdul Aziz al Omari, who arrived at the airport in Portland, Maine. 1.1 INSIDE THE FOUR FLIGHTS Boarding the Flights Boston:American 11 and United 175. Atta and Omari boarded a 6:00 A.M. flight from Portland to Boston’s Logan International Airport.1 When he checked in for his flight to Boston,Atta was selected by a com- puterized prescreening system known as CAPPS (Computer Assisted Passen- ger Prescreening System), created to identify passengers who should be subject to special security measures. Under security rules in place at the time, the only consequence of Atta’s selection by CAPPS was that his checked bags were held off the plane until it was confirmed that he had boarded the air- craft. -

I;Ij:;Fjiran AA Supervisor Atthe Raleigh Reservations Center In

FD 302 Rev. 10-6-95! . _ I -1 Y > .13 6 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION _ 137$ . V Date of transcriptionO 9 1&6/2 O O1 CRAIG MARQUISMARQuIsy,| I | Iemployed as System OperationControl, AMERICAN_AIRLINE$ AA!, 4601 Highway 350," Fort Worth, Texas 76l55,> 817!9677lO0, was interviewed at his place of employmentl After being advised of the identities of the interviewing agents and the purpose of the interview, MARQUIS provided the following information: ' - I ' ~ ' OnSeptember ll, 2001, at approximately 7:25 a.m. Central Standard Time, MARQUIS received a telephone call from the number 3 flight attendant on board Flight ll, identified by the crew manifest as B.A, ONG {ONG!, AA employee number 131804. This telephone call was Efij;i;ij:;fjiran' ' " ved by supervisorNIDIA GONZALES, AA at theRaleigh Reservations1 Center in ort aro ina. The call was transferred to central dispatch in Fort Worth, Texas, because there was a disturbance on board and the flight Y crew was not able to contact the cockpit. ONG wanted central dispatch to contact the cockpit. MARQUIS first confirmed that ONG was an AA flight attendant. ' . ' ' , During this telephone call, ONG reported that there was a passenger on board who was armed with a knife. vThis passenger was seated in 103 and was identified as TQM ELSUQANI phonetic!. when MARQUIS first heard this, he thought that the knife might have been a Swiss army knife of some sort because it was not that uncommon for passengers to have these. ONG then informed MARQUIS that the passenger in seat 9B, DAVID LEWIN, had been fatally stabbed and that the number 1 flight attendant, K.A. -

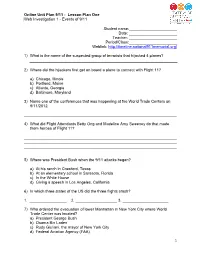

Online Unit Plan 9/11 : Lesson Plan One Web Investigation 1 - Events of 9/11

Online Unit Plan 9/11 : Lesson Plan One Web Investigation 1 - Events of 9/11 Student name:______________________ Date: ______________________ Teacher: ______________________ Period/Class: ______________________ Weblink: http://timeline.national911memorial.org/ 1) What is the name of the suspected group of terrorists that hijacked 4 planes? 2) Where did the hijackers first get on board a plane to connect with Flight 11? a) Chicago, Illinois b) Portland, Maine c) Atlanta, Georgia d) Baltimore, Maryland 3) Name one of the conferences that was happening at the World Trade Centers on 9/11/2012. ______________________________________________________________________ 4) What did Flight Attendants Betty Ong and Madeline Amy Sweeney do that made them heroes of Flight 11? ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ 5) Where was President Bush when the 9/11 attacks began? a) At his ranch in Crawford, Texas b) At an elementary school in Sarasota, Florida c) In the White House d) Giving a speech in Los Angeles, California 6) In which three states of the US did the three flights crash? 1. _________________ 2. ___________________ 3. _____________________ 7) Who ordered the evacuation of lower Manhattan in New York City where World Trade Center was located? a) President George Bush b) Osama Bin Laden c) Rudy Giuliani, the mayor of New York City d) Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) 1 Online Unit Plan 9/11 : Lesson Plan One Web Investigation 1 - Events of 9/11 8) How many survived the North Tower Collapse? _____________ 9) What is the approximate number of deaths on that day, resulting the single largest loss of life resulted from a foreign attack on American soil? _______________________________________________________________ 10) Put in order the events that happened first and put down the times it happened.