Conserving the Grand Canyon Watershed a Proposal for National Monument Designation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scoping Report: Grand Staircase-Escalante National

CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 Scoping Process ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Purpose of Scoping ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Scoping Outreach .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1 Publication of the Notice of Intent ....................................................................................... 3 2.2.2 Other Outreach Methods ....................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Opportunities for Public Comment ................................................................................................ 3 2.4 Public Scoping Meetings .................................................................................................................. 4 2.5 Cooperating Agency Involvement ................................................................................................... 4 2.6 National Historic Preservation Act and Tribal Consultation ....................................................... 5 3 Submission Processing and Comment Coding .................................................................................... 5 -

Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan

Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan El Dorado and Placer Counties, California and Douglas and Washoe Counties, and Carson City, Nevada September 2007 Prepared by: Lake Tahoe Response Plan Area Committee (LTRPAC) Lake Tahoe Geographic Response Plan September 2007 If this is an Emergency… …Involving a release or threatened release of hazardous materials, petroleum products, or other contaminants impacting public health and/or the environment Most important – Protect yourself and others! Then: 1) Turn to the Immediate Action Guide (Yellow Tab) for initial steps taken in a hazardous material, petroleum product, or other contaminant emergency. First On-Scene (Fire, Law, EMS, Public, etc.) will notify local Dispatch (via 911 or radio) A complete list of Dispatch Centers can be found beginning on page R-2 of this plan Dispatch will make the following Mandatory Notifications California State Warning Center (OES) (800) 852-7550 or (916) 845-8911 Nevada Division of Emergency Management (775) 687-0300 or (775) 687-0400 National Response Center (800) 424-8802 Dispatch will also consider notifying the following Affected or Adjacent Agencies: County Environmental Health Local OES - County Emergency Management Truckee River Water Master (775) 742-9289 Local Drinking Water Agencies 2) After the Mandatory Notifications are made, use Notification (Red Tab) to implement the notification procedures described in the Immediate Action Guide. 3) Use the Lake Tahoe Basin Maps (Green Tab) to pinpoint the location and surrounding geography of the incident site. 4) Use the Lake and River Response Strategies (Blue Tab) to develop a mitigation plan. 5) Review the Supporting Documentation (White Tabs) for additional information needed during the response. -

Storm Water Resource Plan | May 2018 Final

AMERICAN RIVER BASIN Storm Water Resource Plan | May 2018 Final Funding for this project has been provided in full or in part through an agreement with the State Water Resources Control Board using funds from Proposition 1. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the foregoing, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. American River Basin Storm Water Resource Plan – Final Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Intent and Content ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Goals and Objectives ............................................................................................................. 2 2.0 WATERSHED IDENTIFICATION ............................................................................................... 3 2.1 Watershed Boundaries (IRWMP Section 2.1) ..................................................................... 3 2.2 Internal Boundaries (IRWMP Sections 2.2, 2.8, & 2.9) ...................................................... 5 2.3 Water and Environmental Resources (IRWMP Sections 2.6.2, 2.6.3, & 2.8) ................. 11 2.4 Natural Watershed Processes (IRWMP Sections 2.6.1, 2.6.2, & 2.6.3) ........................... 13 2.5 Watershed Issues and Priorities (IRWMP Sections 2.6.2, 2.7 to 2.9, & Apdx. B) ......... -

Energy and Mineral Resources, Grand Staircase

Circular 93 Utah Geological Survey Illustration Captions View figure: Circular 93 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15. A Preliminary Assessment of Energy and Table of Contents 1.Preface Mineral Resources within the Grand 2.Summary 3.Introduction Staircase - Escalante National Monument 4.Geology 5.Kaiparowits Plateau coal Compiled by M. Lee Allison, State Geologist field 6.Oil and Gas Potential Contributors: 7.Tar-sand Resources Robert E. Blackett, Editor 8.Non-fuel Minerals and Thomas C. Chidsey Jr., Oil and Gas Mining David E. Tabet, Coal and Coal-Bed Gas 9.Acknowledgments Robert W. Gloyn, Minerals 10.References Charles E. Bishop, Tar-Sands January 1997 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CONTENTS PREFACE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Background Purpose and Scope GEOLOGY Regional Structure Permian through Jurassic Stratigraphy Cretaceous and Tertiary Stratigraphy THE KAIPAROWITS PLATEAU COAL FIELD History of Mining and Exploration Coal Resources Coal Resources on School and Institutional Trust Lands Sulfur Content of Kaiparowits Coal Coal-bed Gas Resources Further Coal Resource Assessments Needed OIL AND GAS POTENTIAL Source Rocks Potential Reservoirs Trapping Mechanisms Exploration and Development Carbon Dioxide Further Oil and Gas Resource Assessments Needed TAR-SAND RESOURCES OF THE CIRCLE CLIFFS AREA NON-FUEL MINERALS AND MINING Manganese Uranium-Vanadium Zirconium-Titanium Gold Copper, Lead and Zinc Industrial and Construction Materials Mining Activity Further Non-Fuel Mineral Resource Assessments Needed ACKNOWLEDGMENTS REFERENCES APPENDIX A: Presidential proclamation APPENDIX B: Summary of the coal resource of Kaiparowits Plateau and its value APPENDIX C: Summary of coal resources on School and Institutional Trust Lands APPENDIX D: Authorized Federal Oil and Gas Leases in the monument ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Grand Circle

Salt Lake City Green River - Moab Salt Lake City - Green River 60min (56mile) Grand Junction 180min (183mile) Colorado Crescent Jct. NM Great Basin Green River NP Arches NP Moab - Arches Goblin Valley 10min (5mile) SP Corona Arch Moab Grand Circle Map Capitol Reef - Green River Dead Horse Point 100min (90mile) SP Moab - Grand View Point NP: National Park 80min (45mile) NM: National Monument NHP: National Histrocal Park Bryce Canyon - Capitol Reef Canyonlands SP: State Park Capitol Reef COLORADO 170min (123mile) NP NP Moab - Mesa Verde Monticello Moab - Monument Valley 170min (140mile) NEVADA UTAH 170min (149mile) Bryce Cedar City Canyon NP Natural Bridges Canyon of the Cedar Breaks NM Blanding Ancients NM Mesa Verde - Monument Valley NM Kodacrome Basin SP 200min (150mile) Valley of Hovenweep 40min 70min NM Cortez (24mile) (60mile) Grand Staircase- the Gods 100min Escalante NM Durango Mt. Carmel (92mile) Muley Point Snow Canyon Jct. SP Goosenecks SP Zion NP Kanab Lake Powell Mexican Hat Mesa Verde Rainbow Monument Valley NP Coral Pink Sand Vermillion Page Bridge NM Four Corners Las Vegas - Zion Dunes SP Cliffs NM Navajo Tribal Park Aztec Ruins NM 170min (167mile) Antelope Pipe Spring NM Horseshoe Shiprock Aztec Bend Canyon Mesa Verde - Chinle 200min (166mile) Mt.Carmel Jct. - North Rim Navajo NM 140min (98mile) Kayenta Farmington Monument Valley - Chinle Mesa Verde - Chaco Culture Valley of Fire Page - North Rim Page - Cameron Page - Monument Valley 140min (134mile) 230min (160mile) SP 170min (124mile) 90min (83mile) Grand Canyon- 130min -

MINERAL POTENTIAL REPORT for the Lands Now Excluded from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

United States Department ofthe Interior Bureau of Land Management MINERAL POTENTIAL REPORT for the Lands now Excluded from Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Garfield and Kane Counties, Utah Prepared by: Technical Approval: flirf/tl (Signature) Michael Vanden Berg (Print name) (Print name) Energy and Mineral Program Manager - Utah Geological Survey (Title) (Title) April 18, 2018 /f-P/2ft. 't 2o/ 8 (Date) (Date) M~zr;rL {Signature) 11 (Si~ ~.u.. "'- ~b ~ t:, "4 5~ A.J ~txM:t ;e;,E~ 't"'-. (Print name) (Print name) J.-"' ,·s h;c.-+ (V\ £uA.o...~ fk()~""....:r ~~/,~ L{ ( {Title) . Zo'{_ 2o l~0 +(~it71 ~ . I (Date) (Date) This preliminary repon makes information available to the public that may not conform to UGS technical, editorial. or policy standards; this should be considered by an individual or group planning to take action based on the contents ofthis report. Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding it!I suitability for a panicular use. The Utah Department ofNatural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users ofthis product. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................................... 4 Oil, Gas, and Coal Bed Methane ........................................................................................................... -

Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain

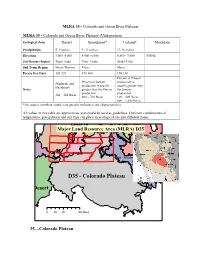

MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus (Utah portion) Ecological Zone Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain Precipitation 5 -9 inches 9 -13 inches 13-16 inches Elevation 3,000 -5,000 4,500 -6,500 5,800 - 7,000 NONE Soil Moisture Regime Typic Ardic Ustic Aridic Aridic Ustic Soil Temp Regime Mesic/Thermic Mesic Mesic Freeze free Days 120-220 120-160 100-130 Percent of Pinyon Percent of Juniper production is Shadscale and production is usually usually greater than blackbrush Notes greater than the Pinyon the Juniper production production 300 – 500 lbs/ac 400 – 700 lbs/ac 100 – 500 lbs/ac 800 – 1,000 lbs/ac *the aspect (north or south) can greatly influence site characteristics. All values in this table are approximate and should be used as guidelines. Different combinations of temperature, precipitation and soil type can place an ecological site into different zones. Rocky Mountains Major Land ResourceBasins and Plateaus Area (MLRA) D35 D36 - Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas, and Foothills D35 - Colorado Plateau Desert 07014035 Miles 35—Colorado Plateau This area is in Arizona (56 percent), Utah (22 percent), New Mexico (21 percent), and Colorado (1 percent). It makes up about 71,735 square miles (185,885 square kilometers). The cities of Kingman and Winslow, Arizona, Gallup and Grants, New Mexico, and Kanab and Moab, Utah, are in this area. Interstate 40 connects some of these cities, and Interstate 17 terminates in Flagstaff, Arizona, just outside this MLRA. The Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest National Parks and the Canyon de Chelly and Wupatki National Monuments are in the part of this MLRA in Arizona. -

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an Evaluation of Population and Habitat Trends Version 3.0 2010

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an evaluation of population and habitat trends Version 3.0 2010 Isolated aspen stand. Photo by Heather McRae. Pygmy nuthatch. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Pumpkin Fire, Kaibab National Forest Mule deer. Photo by Bill Noble Red-naped sapsucker. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Northern Goshawk © Tom Munson Tree encroachment, Kaibab National Forest Prepared by: Valerie Stein Foster¹, Bill Noble², Kristin Bratland¹, and Roger Joos³ ¹Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest Supervisor’s Office ²Forest Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Supervisor’s Office ³Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Williams Ranger District Table of Contents 1. MANAGEMENT INDICATOR SPECIES ................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 Regulatory Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Management Indicator Species Population Estimates ...................................................... 10 SPECIES ACCOUNTS ................................................................................................ 18 Aquatic Macroinvertebrates ...................................................................................... 18 Cinnamon Teal .......................................................................................................... 21 Northern Goshawk ................................................................................................... -

Bat Survey: Scientists Find Variety of Species, Page 3

Award winning! Bat survey: Scientists find variety of species, page 3 Winter 2014 Bi-state compact to preserve Tahoe STEPS TOWARD REVITALIZATION turns 45 years old Staff Report Redevelopment projects expected to aid environment, economy The partnership between California and Nevada that created the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency By Devin Middlebrook (TRPA) turned 45 years old in Tahoe Regional Planning Agency December 2014 and is approaching a half-century of progress in the protection and restoration of Lake Lake Tahoe’s communities have struggled Tahoe and its treasured environment. for decades from environmental, economic, and President Richard Nixon signed social pressures. The advent of Native American the bi-state compact to create the gaming throughout Northern California drove TRPA on Thursday, Dec. 18, 1969. massive casino job losses, which were compounded Nixon’s signature in the Oval Office followed the compact’s ratification by the recent recession. To many, a visible clue by Congress, approval by both was the number of run-down or vacant buildings states’ legislatures, and signatures of around the Lake. Many of these buildings were former governors Ronald Reagan in constructed in the 1960s, prior to the Tahoe Regional California and Paul Laxalt in Nevada. Planning Agency being established, during a period U.S. Sen. Alan Bible (D-Nev.) of rampant growth with a lack of development introduced legislation to approve the bi-state compact in Congress. Bible regulations. Fifty years later, as the recession took called Nixon’s signature of the bill hold, the Region looked tired and in disrepair. “the best news possible for those Times are changing. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

1788 Sept. 18 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1996 a lot of you will want to be involved in that National Monument becomes a great pillar and to be heard as well. in our bridge to tomorrow. Let us always remember, the Grand Stair- Thank you, and God bless you all. case-Escalante is for our children. For our children we have worked hard to make sure NOTE: The President spoke at 12:10 p.m. outside El Tovar Lodge. In his remarks, he referred to that we have a clean and safe environment, Rob Arnberger, Superintendent, Grand Canyon as the Vice President said. I appreciate what National Park; Norma Matheson, widow of former he said about the Yellowstone, the Mojave Utah Gov. Scott Matheson; and Gov. Michael O. Desert, the Everglades, the work we have Leavitt of Utah. done all across this country to try to preserve our natural heritage and clean up our envi- ronment. I hope that we can once again pur- Proclamation 6920ÐEstablishment sue that as an American priority without re- of the Grand Staircase-Escalante gard to party or politics or election seasons. National Monument We all have the same stake in our common September 18, 1996 future. If you'll permit me a personal note, an- By the President of the United States other one, it was 63 years ago that a great of America Democrat first proposed that we create a na- A Proclamation tional monument in Utah's Canyonlands. His The Grand Staircase-Escalante National name was Harold Ickes. He was Franklin Monument's vast and austere landscape em- Roosevelt's Interior Secretary. -

Hiking the Grand Staircase National Parks

HIKING THE GRAND STAIRCASE NATIONAL PARKS TRIP SUMMARY HIGHLIGHTS • Hiking through two billion years of geologic time as we descent 3000 feet into the Grand Canyon • Seeing Bryce Canyon's hoodoos as you hike through them • Experiencing the peace of Zion Canyon from the floor of the canyon and the rim • Learning about the diverse and fascinating geology of the area • Gazing upward at more stars than you ever knew existed Phone: 877-439-4042 Outside the US: 410-435-1965 Email: [email protected] TRIP AT A GLANCE Location: North Rim Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce National Parks Activities: Hiking Arrive: Plan to meet at 12pm at the Las Vegas airport on Day 1 Depart: Las Vegas airport in time for flights out after 7pm on the last day. TRIP OVERVIEW The Grand Staircase refers to an immense sequence of sedimentary rock layers that stretch from Bryce Canyon National Park and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, through Zion NP and Grand Canyon NP. The rock that is at the bottom of Bryce forms the top of Zion and the bottom rock of Zion is the top layer of the Grand Canyon. We've picked three National Parks along the Grand Staircase to hike: Zion, Bryce and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon National Parks are all spectacular and all very different from the others. The Grand Canyon is vast: it is 10 miles from one side to the other and a mile deep. Bryce is known for amazing hoodoos, the brightly colored spires of varied shapes; and Zion, with the tallest layer of Redwall Limestone of any canyon, is both majestic and a much more intimate canyon that fully deserves its name. -

A Proposal to Conduct a Water Resouces

AN ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, KANE AND TWO MILE RANCHES, EASTERN ARIZONA STRIP: 30 SEPTEMBER 2005 DRAFT FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Stevens Ecological Consulting, LLC P.O. Box 1315 Flagstaff, AZ 86002 [email protected] Prepared for: Grand Canyon Wildlands Council, Inc. P.O. Box 1594 Flagstaff, AZ 86002 (928) 556-9306 [email protected] For submission to: The Grand Canyon Trust Attn: Mr. Ethan Aumack N. Ft. Valley Rd. Flagstaff, AZ 86001 [email protected] 30 September 2005 GCWC DRAFT FINAL GCT WATER RESOURCES REPORT - 30 SEPT. 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables List of Figures List of Appendices Acknowledgements Executive Summary Introduction Project Tasks Task 1: Existing data on water resources distribution and study site selection Introduction Methods Results and Discussion Task 2: Historical Land Use of the Eastern Arizona Strip – Kim Crumbo Prehistory Exploration and Settlement Grand Canyon Game Preserve Logging Grazing Task 3: Arial Reconnaissance of the Eastern Arizona Strip Introduction Recommendations Task 4: Field site visits Introduction Methods Results and Discussion Task 5: Water resources assessment and recommendations Introduction Methods Results and Discussion General Recommendations Site-specific Recommendations References Cited Appendices 1 GCWC DRAFT FINAL GCT WATER RESOURCES REPORT - 30 SEPT. 2005 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1: Water resource site scoring and ranking criteria Table 1.2: Primary (*) and alternate sites used for inventory in 2005 Table 3.1: Several apparently