Solidarity Food Cooperatives?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Social Teaching Theme 6 Solidarity

Catholic Social Teaching Theme 6 Solidarity We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. We are our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers, wherever they may be. Loving our neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world. At the core of the virtue of solidarity is the pursuit of justice and peace. Pope Paul VI taught that “if you want peace, work for justice.”1 The Gospel calls us to be peacemakers. Our love for all our sisters and brothers demands that we promote peace in a world surrounded by violence and conflict. Scripture • Genesis 12:1-3 God blessed Israel so that all nations would be blessed through it. • Psalms 72 Living in right relationship with others brings peace. • Psalms 122 Peace be with you! For the sake of the Lord, I will seek your good. Zechariah 8:16 These are the things you should do: Speak truth, judge well, make peace. • Matthew 5:9 Blessed are the peacemakers, they will be called children of God. • Matthew 5:21-24 Be reconciled to one another before coming to the altar. • Romans 13:8-10 Living rightly means to love one another. • 1 Corinthians 12:12-26 If one member of Christ’s body suffers, all suffer. If one member is honored, all rejoice. • Colossians 3:9-17 Above all, clothe yourself with love and let the peace of Christ reign in your hearts. • 1 John 3:16-18 The love of God in us is witnessed to by our willingness to lay down our lives for others as Christ did for us. -

Catholic Social Teaching: a Tradition Through Quotes

Catholic Social Teaching: A Tradition through Quotes "When I fed the poor, they called me a saint. When I asked why the poor had no food, they called me a Communist." —Archbishop Dom Hélder Câmara "If you want peace, work for justice." —Blessed Paul VI "Justice comes before charity." —St. John XXIII "Peace is not the product of terror or fear. Peace is not the silence of cemeteries. Peace is not the silent result of violent repression. Peace is the generous, tranquil contribution of all to the good of all. Peace is dynamism. Peace is generosity. It is right and it is duty." —Archbishop Óscar Romero "Peace is not merely the absence of war; nor can it be reduced solely to the maintenance of a balance of power between enemies; nor is it brought about by dictatorship. Instead, it is rightly and appropriately called an enterprise of justice." —The Bishops of the Second Vatican Council “[Catholics can] in no way convince themselves that so enormous and unjust an inequality in the distribution of this world's goods truly conforms to the designs of the all-wise Creator." —Pope Pius XI “Miss no single opportunity of making some small sacrifice, here by a smiling look, there by a kindly word; always doing the smallest things right, and doing all for love.” —St. Thérèse of Lisieux “The bread you store up belongs to the hungry; the cloak that lies in your chest belongs to the naked; the gold you have hidden in the ground belongs to the poor.” –St. Basil the Great “Do not grieve or complain that you were born in a time when you can no longer see God in the flesh. -

Catholic Social Teaching Workshop Notes Solidarity

; Catholic Social Teaching Workshop Notes Solidarity SLIDE ONE – HOLDING SLIDE LEADER’S NOTES This presentation lasts up to 30 minutes. We recommend you deliver the whole workshop but please feel free to use the slides and script as time and circumstances allow. To reduce time, omit extension tasks. This is one of five workshops referencing the principles of Catholic Social Teaching. Catholic Social Teaching (CST) is based on Scripture, Tradition and Church Teaching as given by popes, bishops and theologians. It offers a set of principles to help us think about how we should interact with others, the choices we make, and how we view creation. For more information about Catholic Social Teaching please visit www.catholicsocialteaching.org.uk START OF PRESENTATION SLIDE TWO This workshop has been prepared by Missio, Pope Francis’ official charity for overseas mission. Mission simply means being sent out to deliver God’s love to others through our actions and words. When we look at the world around us, it’s clear that there’s a great need for God’s mercy and love. We can feel overwhelmed by news of terrible violence, unfairness, and suffering. The Church encourages us not to turn away in despair, but to look at how things could be. To ask ourselves: What kind of world do I want to be a part of? Then to consider: What can we offer, individually and as a community, to build it? Pope Francis has spoken to young people directly about how, through their desire to make the world a better place, they have the potential to be great missionaries of God’s love. -

Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland

Open Cultural Studies 2019; 3: 469-484 Research Article Jennifer Ramme* Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0040 Received October 30, 2018; accepted May 30, 2019 Abstract: Due to the attempts to restrict the abortion law in Poland in 2016, we could observe a new broad- based feminist movement emerge. This successful movement became known worldwide through the Black Protests and the massive Polish Women’s Strike that took place in October 2016. While this new movement is impressive in its scope and can be described as one of the most successful opposition movements to the ethno-nationalist right wing and fundamentalist Catholicism, it also deploys a patriotic rhetoric and makes use of national symbols and categories of belonging. Feminism and nationalism in Poland are usually described as in opposition, although that relationship is much more complex and changing. Over decades, a general shift towards right-wing nationalism in Poland has occurred, which, in various ways, has also affected feminist actors and (counter)discourses. It seems that patriotism is used to combat nationalism, which has proved to be a successful strategy. Taking the example of feminist mobilizations and movements in Poland, this paper discusses the (im)possible link between patriotism, nationalism and feminism in order to ask what it means for feminist politics and female solidarity when belonging is framed in different ways. Keywords: framing belonging; social movements; ethno-nationalism; embodied nationalism; public discourse A surprising response to extreme nationalism and religious fundamentalism in Poland appeared in the mass mobilization against a legislative initiative introducing a total ban on abortion in 2016, which culminated in a massive Women’s Strike in October the same year. -

CST 101 Discussion Guide: Solidarity

CST 101 SOLIDARITY A discussion guide from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and Catholic Relief Services OPENING PRAYER: Together, pray, “Because We Are Yours.” WATCH: “CST 101: Solidarity” on YouTube. PRAY WITH SCRIPTURE: Read this Scripture passage twice. Invite participants to reflect silently after it is read the first time. “Indeed, the parts of the body that seem to be weaker are all the more necessary, and those parts of the body that we consider less honorable we surround with greater honor, and our less presentable parts are treated with greater propriety, whereas our more presentable parts do not need this. But God has so constructed the body as to give greater honor to a part that is without it, so that there may be no division in the body, but that the parts may have the same concern for one another. If [one] part suffers, all the parts suffer with it; if one part is honored, all the parts share its joy.” (1 Corinthians 12:22-26) SHARE: To show compassion, from the root words “com” and “passion,” means “to suffer with” another. ■ When have you experienced deep compassion for the suffering of another? ■ Have you ever experienced compassion for the suffering of a stranger? REFLECT ON TRADITION: Read these passages aloud. “[Solidarity] is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the Photo courtesy of Brother Mickey McGrath, OSFS common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all.” —St. -

THE PRINCIPLE of SOLIDARITY A. Meaning and Value 192. Solidarity

THE PRINCIPLE OF SOLIDARITY a. Meaning and value 192. Solidarity highlights in a particular way the intrinsic social nature of the human person, the equality of all in dignity and rights and the common path of individuals and peoples towards an ever more committed unity. Never before has there been such a widespread awareness of the bond of interdependence between individuals and peoples, which is found at every level [413]. The very rapid expansion in ways and means of communication “in real time”, such as those offered by information technology, the extraordinary advances in computer technology, the increased volume of commerce and information exchange all bear witness to the fact that, for the first time since the beginning of human history, it is now possible — at least technically — to establish relationships between people who are separated by great distances and are unknown to each other. In the presence of the phenomenon of interdependence and its constant expansion, however, there persist in every part of the world stark inequalities between developed and developing countries, inequalities stoked also by various forms of exploitation, oppression and corruption that have a negative influence on the internal and international life of many States. The acceleration of interdependence between persons and peoples needs to be accompanied by equally intense efforts on the ethical-social plane, in order to avoid the dangerous consequences of perpetrating injustice on a global scale. This would have very negative repercussions even in the very countries that are presently more advantaged[414]. b. Solidarity as a social principle and a moral virtue 193. -

The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository The Concept of Solidarity in Anarchist Thought by John Nightingale A Doctoral Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Loughborough University September 2015 © John Nightingale 2015 Abstract This thesis makes an original contribution to knowledge by presenting an analysis of anarchist conceptions of solidarity. Whilst recent academic literature has conceptualised solidarity from a range of perspectives, anarchist interpretations have largely been marginalised or ignored. This neglect is unjustified, for thinkers of the anarchist tradition have often emphasised solidarity as a key principle, and have offered original and instructive accounts of this important but contested political concept. In a global era which has seen the role of the nation state significantly reduced, anarchism, which consists in a fundamental critique and rejection of hierarchical state-like institutions, can provide a rich source of theory on the meaning and significance of solidarity. The work consists in detailed analyses of the concepts of solidarity of four prominent anarchist thinkers: Michael Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Murray Bookchin and Noam Chomsky. The analytic investigation is led by Michael Freeden’s methodology of ‘ideological morphology’, whereby ideologies are viewed as peculiar configurations of political concepts, which are themselves constituted by sub-conceptual idea- components. Working within this framework, the analysis seeks to ascertain the way in which each thinker attaches particular meanings to the concept of solidarity, and to locate solidarity within their wider ideological system. Subsequently, the thesis offers a representative profile of an ‘anarchist concept’ of solidarity, which is characterised by notions of universal inclusion, collective responsibility and the social production of individuality. -

1 Transnational Hindutva Networks in United States 1 Over the Last

Transnational Hindutva Networks in United States 1 Over the last several decades, a transnational network of American groups affiliated with Hindu nationalist organizations has embedded itself in the Indian diaspora in the United States.2 This network deserves special attention in the context of the recent debate around citizenship laws in India that target religious minority groups, specifically Muslims.3 The National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Constitution Amendment Act (CAA) and the protest against it cannot be understood in isolation from the growing prominence of the Hindutva ideology in India. Through the ideological lens of Hindutva, India is an aspiring Hindu state, which would include the Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs as organically deriving from India, but not Muslims, because Islam is characterized as an alien and invading religion. The citizenship laws also assert that all non-Muslims excluded in the nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) would re-qualify for citizenship via Constitution Amendment Act (CAA), while the Muslims living in India for generations would not. Instead, the Indian Muslims could be subject to severe punitive consequences including “statelessness, deportation, or prolonged detention”.4 Under such circumstances, and in the context of the riots in North East Delhi that experts have categorized as pogrom against Muslims5, the purpose of this testimony is two fold. First, it argues that it is unlikely that transnational Hindu nationalist network6 based in the United States is immune to Hindutva, the ethnonational exclusionary political philosophy propagated in India by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the India-based Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization founded in 1925.7 Reference to 1 This testimony is written by a scholar of South Asia. -

Concept of Nature from Rerum Novarum to Laudato Si’ Barbara E

1 Concept of Nature from Rerum novarum to Laudato si’ Barbara E. Wall This chapter, from a philosopher, explores the treatment of the nature of the physical world in Catholic social teaching (CST) from Rerum novarum (RN) to Laudato si’ (LS). The concept of nature is not easy to understand. It is often identified with the physical world, which is ever changing. With regard to CST, the use of “nature,” or physis, refers to the physical world. In Plato’s Timaeus, we find that a craftsman creates the world according to the ideas, or universal forms,1 which is a kind of internal organizational principle that one might refer to as “the structure of things.” Aristotle’s view of nature and natural law provided a foundation for RN’s retrieval of a Thomistic philosophical foundation for restoring order in the tumultuous, if not chaotic, social world of the late nineteenth century.2 The language of CST uses the term “nature” to refer to the physical world—a world that has a relationship to God. However, it does not use the language of “creation” to speak of this world until the CST documents of the late twentieth century.3 Since 1 Plato, Timaeus 31b. 2 For treatment of the Neo-Thomistic influences on the early formation of natural law ethics, which provided a conceptual vehicle for exploring the moral guidance for understanding “natural law” as a mandate for the common good, see Stephen J. Pope, “Natural Law in Catholic Social Teachings,” and Thomas A. Shannon, “Rerum Novarum,” in Modern Catholic Social Teaching: Commentaries and Interpretations, ed. -

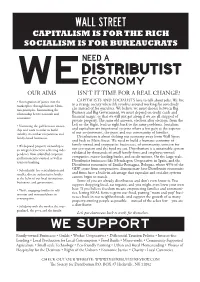

Distributist Weeconomy Our Aims Isn’T It Time for a Real Change?

WALL STREET CAPITALISM IS FOR THE RICH SOCIALISM IS FOR BUREAUCRATS NEED A DISTRIBUTIST WEECONOMY OUR AIMS ISN’T IT TIME FOR A REAL CHANGE? • Reintegration of justice into the CAPITALISTS AND SOCIALISTS love to talk about jobs. We live marketplace through historic Chris- in a strange society where life revolves around working for somebody tian principles, harmonizing the else instead of for ourselves. We believe we must choose between Big relationship between morals and Business and Big Government, we must depend on credit cards and economics. financial magic, or that we will just get along if we are all stripped of private property. The same old answers, election after election, from the • Narrowing the gulf between owner- Left or the Right, lead us right back to the same problems. Socialism ship and work in order to build and capitalism are impersonal systems where a few gain at the expense stability via worker cooperatives and of our environment, the poor, and our community of families. family-based businesses. Distributism is about shifting our economy away from Wall Street and back to Main Street. We need to build a humane economy of • Widespread property ownership as family-owned and cooperative businesses, of community, concern for an integral element in achieving inde- our eco-system and the food we eat. Distributism is a sustainable system pendence from unbridled corporate validated by thousands of small family firms and employee-owned and bureaucratic control, as well as companies, micro-lending banks, and credit unions. On the large-scale, usurious banking. Distributist businesses like Mondragon Cooperative in Spain, and the Distributist economies of Emilia-Romagna, Bologna, where 45% of the • Subsidiarity: less centralization and GDP come from cooperatives, demonstrate how Distributist economies smaller, diverse authoritative bodies and firms have a built-in advantage that capitalist and socialist systems at the helm of our local institutions, cannot begin to match. -

Catholic Social Thought (CST) and Subsidiarity Seal of the Society of Jesus by Fred Kammer, S.J

Understanding CST Catholic Social Thought (CST) and Subsidiarity Seal of the Society of Jesus By Fred Kammer, S.J. ”Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do.” —Pope Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno In 1931, in the encyclical through subsidiarity that larger political economic life cannot be left to a free Quadragesimo Anno, Pope Pius XI entities should not absorb the effective competition of forces. For from this introduced a critically important Catholic functions of smaller ones. This was in part source, as from a poisoned spring, have social teaching concept, one which has a reaction against the centralizing originated and spread all the errors of remained current in political debates tendencies of socialism at the time. individualist economic teaching.”4 In today. In his discussion of the social order, However, if smaller, more localized entities 2009, Pope Benedict further clarified: he stated the principle: cannot or will not cope adequately with a The principle of subsidiarity must problem, then larger entities—the state, for As history abundantly proves, it is true that remain closely linked to the principle of instance—have a responsibility to act. on account of changed conditions many solidarity and vice versa, since the former The principle, however, is not just things which were done by small associations without the latter gives way to social political. -

The Pope and Henry George: Pope Leo XIII Compared with Henry George, on the Ownership of Land and Other Natural Resources

Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics Volume 8 Issue 2 Article 2 2018 The Pope and Henry George: Pope Leo XIII compared with Henry George, on the ownership of land and other natural resources. A possible rapproachement? John Pullen uni, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/solidarity ISSN: 1839-0366 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING This material has been copied and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Notre Dame Australia pursuant to part VB of the Copyright Act 1969 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Recommended Citation Pullen, John (2018) "The Pope and Henry George: Pope Leo XIII compared with Henry George, on the ownership of land and other natural resources. A possible rapproachement?," Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/solidarity/vol8/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Pope and Henry George: Pope Leo XIII compared with Henry George, on the ownership of land and other natural resources. A possible rapproachement? Abstract The encyclical, Rerum Novarum, issued by Pope Leo XIII in 1891 was interpreted by Henry George as a criticism of the views he had expressed in Progress and Poverty, 1879, and other writings.