Base Layer (Underwear Layer): Wicks Sweat Off Your Skin 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Departure Information

Pre-Departure Information FROM FRANCE TO SPAIN: HIKING IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY Table of Contents TRAVEL INFORMATION Passport Visas Money Tipping Special Diets Communications Electricity MEDICAL INFORMATION Inoculations Staying Healthy HELPFUL INFORMATION Photography Being a Considerate Traveler Words and Phrases PACKING LIST The Essentials WT Gear Store Luggage Notes on Clothing Clothing Equipment Personal First Aid Supplies Optional Items Reminders Before You Go WELCOME! We’re delighted to welcome you on this adventure! This booklet is designed to guide you in the practical details for preparing for your trip. As you read, if any questions come to mind, feel free to give us a call or send us an email—we’re here to help. PLEASE SEND US Trip Application: Complete, sign, and return your Trip Application form as soon as possible if you have not already done so. Medical Form: Complete, sign, and return your Medical Form as soon as possible if you have not already done so. Air Schedule: Please forward a copy of your email confirmation, which shows your exact flight arrival and departure times. Refer to the Arrival & Departure section of the Detailed Itinerary for instructions. Please feel free to review your proposed schedule with Wilderness Travel before purchasing your tickets if you have any questions about the timing of your arrival and departure flights or would like to confirm we have the required minimum number of participants to operate the trip. Vaccination Card: Please send us a photo or scanned copy of your completed Covid-19 Vaccination Card if you have not already done so. -

All Sizing Is US. Parkas: Refer to Canada Goose Parka Relaxed Fit

All sizing is US. Parkas: Refer to Canada Goose Parka Relaxed Fit sizing chart here Boots: Sorel Boot sizing chart here. Snow pants we carry a few different brands: Misty Mountain, Choko and GKS for women plus the Helly Hansen brand for men. Unfortunately, we don’t have a quick reference sizing chart for these companies. If you’re comfortable you can provide your weight, height and basic measurements and we can select what would be the best possible fit. Please note sizes/brands may be substituted if first option is not available. We have a few models/styles of parkas that fit larger such as the Mantra. We also carry OSC Parkas in inventory that are very comparable in warmth to the Canada Goose brand and are excellent as well in addition to Baffin boots. WINTER CLOTHING RENTAL - Q & A. Q. How do I choose the right size of winter clothing? Early Winter/Early Spring Season (October – December 01; March 15 – April 01) Select the size you normally wear. If you wear a medium jacket, then order the same size parka, the same general theory applies for all of the articles of clothing. For example. If you wear a small glove, then choose a small mitt. Winter Season(December – March 14) Select one size larger in a parka then you normally wear. For example: If you wear a size Ladies Medium, suggest you choose a size Large. This allow for more airspace that will keep you warm and allow for additional layer (warm sweater or fleece) Boots: Come in full sizes only. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Rural Dress in Southwestern Missouri Between 1860 and 1880 by Susan

Rural dress in southwestern Missouri between 1860 and 1880 by Susan E. McFarland Hooper A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Textiles and Clothing Major: Textiles and Clothing Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 SOURCES OF COSTUME, INFORMATION 4 SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI, 1860 THROUGH 1880 8 Location and Industry 8 The Civil War 13 Evolution of the Towns and Cities 14 Rural Life 16 DEVELOPMENT OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL INDUSTRIES BY 1880 19 Textiles Industries 19 Apparel Production 23 Distribution of Goods 28 TEXTILES AND CLOTHING AVAILABLE IN SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 31 Goods Available from 1860 to 1866 31 Goods Available after 1866 32 CLOTHING WORN IN RURAL SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 37 Clothing Worn between 1860 and 1866 37 Clothing Worn between 1866 and 1880 56 SUMMARY 64 REFERENCES 66 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 70 GLOSSARY 72 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Selected services and businesses in operation in Neosho, Missouri, 1860 and 1880 15 iv LIST OF MAPS Page Map 1. State of Missouri 9 Map 2. Newton and Jasper Counties, 1880 10 v LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS Page Photograph 1. Southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 40 Photograph 2. Detail, southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 41 Photograph 3. George and Jim Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 46 Photograph 4. George W. Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 47 Photograph 5. Front pieces of manls vest from steamship Bertrand, 1865 48 Photograph 6. -

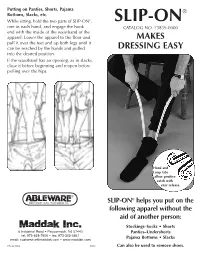

SLIP-ON®, SLIP-ON One in Each Hand, and Engage the Hook CATALOG NO

Putting on Panties, Shorts, Pajama ® Bottoms, Slacks, etc. While sitting, hold the two parts of SLIP-ON®, SLIP-ON one in each hand, and engage the hook CATALOG NO. 73839-0000 end with the inside of the waistband of the apparel. Lower the apparel to the floor and MAKES pull it over the feet and up both legs until it can be reached by the hands and pulled DRESSING EASY into the desired position. If the waistband has an opening, as in slacks, close it before beginning and reopen before pulling over the hips. Hook and Loop tabs allow positive catch with easy release. SLIP-ON® helps you put on the following apparel without the aid of another person: Stockings–Socks • Shorts 6 Industrial Road • Pequannock, NJ 07440 Panties–Undershorts tel: 973-628-7600 • fax: 973-305-0841 email: [email protected] • www.maddak.com Pajama Bottoms • Slacks 973839002 0803 Can also be used to remove shoes. INSTRUCTIONS Engage the gear-like teeth to make SLIP-ON® As shown in Figure 3, keep the hook ends operable. As shown in Figure 1, hold engaged with the stocking and separate SLIP-ON® in one hand and insert the two parts of SLIP-ON®, holding one in the hook ends inside the each hand. Pull the stocking over the heel top opening of stocking. and up the leg to the point where it can Hold SLIP-ON® in the be reached by hand and adjusted to the left hand if you are desired position. putting the stocking Caution: When using with sheer stockings on the left foot; in the engage hook ends with reinforced top band right hand for the right to avoid rupturing the sheer knit. -

Clothing Guidelines

Clothing Guidelines We fully dress the deceased to preserve their dignity and help them look as “normal” as possible. As a general rule, the clothing is not returned to the family*, however jewelry and other items that are displayed in the casket can either be returned or left with the deceased. You may bring the clothing with you to the arrangement meeting or bring it to the funeral home later. However, we do prefer to have the clothing by 12 noon at least one day before the visitation. If you have any questions, please call our offices at 440-516-5555 or 216-291-3530. Clothing for the deceased should include: Long sleeves and a high neckline Undergarments - including underwear, socks, t-shirt, bra, stockings, etc. as appropriate Shoes (optional) Glasses, a wig or a hairpiece (if normally worn) Hair dye MUST be provided by the family and at the funeral home by 12 noon the day before the visitation A recent photo (You can e-mail photo to [email protected]) Jewelry, a rosary or any other items to be placed in the casket. All items (clothing, jewelry, etc.) will be inventoried by a DeJohn Funeral Homes staff person when you bring them in. We will ask you to sign the inventory list before you leave to ensure we have itemized all of the pieces. * If there is an article of clothing you wish to be returned, please be sure to tell the staff person when you bring the clothing in. Rev. 5-2016 Willoughby Hills ~ Chesterland ~ South Euclid ~ Chardon Clothing List FULL NAME OF DECEASED: Would you like the articles of clothing your loved one was wearing when taken into our care, or extra clothing, RETURNED to the family -or- DISCARDED by the funeral home? (please circle) Simply indicate below if you are bringing in the following items. -

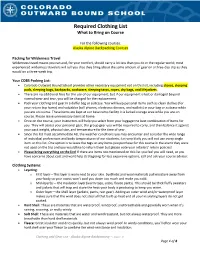

Required Clothing List What to Bring on Course

Required Clothing List What to Bring on Course For the following courses: Alaska Alpine Backpacking Courses Packing for Wilderness Travel Wilderness travel means you can and, for your comfort, should carry a lot less than you do in the regular world; most experienced wilderness travelers will tell you that they bring about the same amount of gear on a three-day trip as they would on a three-week trip. Your COBS Packing List: • Colorado Outward Bound School provides other necessary equipment not on this list, including stoves, sleeping pads, sleeping bags, backpacks, cookware, sleeping tarps, ropes, dry bags, and lifejackets. • There are no additional fees for the use of our equipment, but if our equipment is lost or damaged beyond normal wear and tear, you will be charged for the replacement. • Pack your clothing and gear in a duffel bag or suitcase. You will keep personal items such as clean clothes (for your return trip home) and valuables (cell phones, electronic devices, and wallets) in your bag or suitcase while you are on course. These items are kept at our base camp facility in a locked storage area while you are on course. Please leave unnecessary items at home. • Once on the course, your instructors will help you select from your luggage the best combination of items for you. They will assess your personal gear, the group gear you will be required to carry, and then balance it against your pack weight, physical size, and temperature for the time of year. • Since this list must accommodate ALL the weather conditions you may encounter and consider the wide range of individual preferences and body temperatures of our students, it is very likely you will not use every single item on this list. -

Carbonx Ultimate Baselayer Solutions Include: Long-Sleeve Tops And

“MY HUSBAND WAS AT WORK IN A STEEL THE CARBONX ULTIMATE BASELAYER—THE ONLY MILL, ON A BOBCAT PUSHING HOT SLAG. CHOICE WHEN SAFETY MATTERS MOST HOT MET COLD AND MOLTEN SLAG Flame-resistant (FR) undergarments play an EXPLODED ALL OVER HIS BODY. THE essential role in protecting wearers against STEEL MELTED THE SAFETY BELT ON THE serious burn injuries and more common BOBCAT SO HE COULDN’T FREE HIMSELF. nuisance burns. In dangerous situations, HE WAS WEARING THE NORMAL STEEL having this base layer of defense close to the skin may buy the wearer critical time to MILL GREENS, BUT HE HAD ALSO WORN escape without severe or life-threatening HIS CARBONX UNDERWEAR THAT NIGHT injuries. DUE TO THE COLD EVENING. THE GREENS HE WAS WEARING BURNT OFF OF HIM The CarbonX® UltimateTM Baselayer ALMOST COPLETELY. THE CARBONX HOOD provides the highest level of protection for professionals working in extreme AND UNDERWEAR HE HAD ON SAVED HIS conditions where safety matters most. It is LIFE.” also an ideal choice for cooler climates and winter conditions. The Ultimate Baselayer —WIFE OF A STEEL MILL ACCIDENT VICTIM is made from our DJ-77 black fabric, an 8 oz/yd2 double jersey interlock knit comprised of a propriety blend of high- performance fibers. Constructed to be truly non-flammable, our Ultimate Baselayer delivers: Unmatched Protection: It will not burn, melt, or ignite, and significantly outperforms competing FR products when subjected to direct flame, extreme heat, molten metal, flammable liquids, certain chemicals, and arc flash. Even after intense exposure, our Ultimate Baselayer maintains its strength and integrity and continues ULTIMATE BASELAYER ULTIMATE THAT SOLUTIONS TOE HEAD TO COVER to protect. -

Winter Hut Trip Packing List

Red Rock Recovery Center Experiential Program Packing List Winter Winter Boots Insulated, waterproof, and above the ankle. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $29.84 Men’s winter boots (grey moon boots)- $19.68 Women’s Ozark Trail winter boots- $46.86 Available at REI: Women’s and men’s Sorel Caribou boots- $150 Men’s Kamik William snow boot- $149.95 Men’s North Face Chilkat- $150 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Women’s Northside Kathmandu boots- $74.99 Women’s Northside Bishop Boots- $54.99 Women’s Kamik Momentum- $84.99 Men’s Kamik Nation Plus boots- $79.99 Socks 2 heavy weight wool. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Men’s Kodiak wool socks (2 pack)- $9.48 Men’s Dickies crew work socks- $8.77 Available at REI: REI Coolmax midweight hiking crew socks- $13.95 Fox River Adventure cross terrain 2 pack- $19.95 Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Fox River boot and field thermal socks $7.99 Fox River work thermal 2 pack- $15.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus: Fox River hike, trek, and trail- $8.99 Available at Army/Navy Surplus Outlet: Fox River work steel toe crew 6 pack- $20 Long Underwear 1 set, top & bottom. Midweight, heavyweight, or "expedition weight”. Base layers should be synthetic, silk, or wool. Look for new anti-microbial fabrics that don't get stinky. No cotton. Available at Wal-Mart: Women’s Climate Right by CuddlDuds long sleeve crew and leggings- $9.96 each Men’s Russel base layers top and bottom- $12.72 each Available at Sportsman’s Warehouse: Coldpruf enthusiast base layer top and bottom- $17.99 each Sweater Heavy fleece, synthetic, thin puffy, or wool. -

Fancy Dress Party

Fancy Dress Party Barbara and Alison want to find a way to get Albert, Barbara’s husband to admit he is a cross- dresser. They hit on the perfect solution, a fancy dress party to which everyone, well nearly everyone, has to wear a costume which involves wearing silky lingerie and stockings underneath. 1 Alison decided she would go and see her sister Barb at the beginning of October. They planned to go shopping again at the Mall, it was so much fun last time they went flashing on the up escalators. Alison had intended to take her 18 year old son Mike with her but he protested that he had too much college work to do and he could the washing and ironing whilst she was away. 2 She trusted him to do the washing and ironing as she knew he loved ironing all her silky slips but she wondered what else he might get up to whilst she was away for the weekend. 3 So Alison travelled up to Cheshire, on her own. When she got there she greeted both Barbara, and her husband Arnold, with a peck on the cheek. After asking how her journey was Arnold excused himself and went upstairs to read an ebook on his new Kindle, a birthday present from Barbara. The two sisters sat down with a cup of coffee and rolled back the years. They recalled the flashing they had done on their last shopping trip to the Mall. This triggered a memory for Barbara about when she was about 16 and still dancing. -

Nomex® Undergarments Hearing Protection

Prices shown are current as of January 16, 2019. Nomex® Undergarments OMP Nomex® Undergarments, FIA and SFI Approved OMP Sport Nomex® Undergarments, FIA and SFI Approved SAFETY OMP Undergarment Measurements Top Bottom Order Chest Waist Size Size Size S 34 - 36" 29 - 32" M 37 - 39" 33 - 34" L 40 - 42" 35 - 37" OMP Sport Undergarment XL 43 - 46" 38 - 40" Measurements Top Bottom XXL 47 - 50" 41 - 46" Order Chest Waist Inseam are constructed of a very smooth, soft knit fabric. OMP Nomex® Undergarments Size Size Size This is not the typical "waffle weave" long underwear! External seams further enhance comfort and reduce pressure points. The Top features long sleeves and a short mock S 36 - 39" 29 - 32" 28 - 31" turtleneck. The Bottoms have full-length legs, a narrow elastic waist for comfort, and no fly to compromise safety. The two-layer Balaclava features a single large eye opening M 39 - 42" 33 - 34" 30 - 32" and a sculpted neck to prevent bunching above the shoulders. All are FIA 8856-2000 and L 42 - 45" 35 - 37" 32 - 34" SFI 3.3 approved. Natural off-white color only. OMP Nomex® Underwear Top, FIA & SFI ....... Part No. 2153-005-Size .......... $109.00 XL 45 - 48" 38 - 40" 33 - 35" OMP Nomex® Underwear Bottom, FIA & SFI ... Part No. 2153-006-Size ........... $89.00 XXL 48 - 51" 41 - 46" 34 - 36" OMP Nomex® 2-Layer Balaclava, FIA & SFI..... Part No. 2153-001 ................ $49.00 OMP Nomex® Socks, FIA & SFI, pair ............ Part No. 2153-002-Size ........... $29.00 1 are designed and manufactured with the Socks are available in Small (shoe sizes 5 ⁄2 - 8), Medium (8 - 10), and Large (10 - 13). -

Crochet Bikini : 10 Adorable Crochet Bikini Patterns Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CROCHET BIKINI : 10 ADORABLE CROCHET BIKINI PATTERNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rosalie Love | 26 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781545273524 | English | none Crochet Bikini : 10 Adorable Crochet Bikini Patterns PDF Book By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. I need a swimsuit. Most of them have a bikini top that matches the mermaid tail, which is fairly classic for this type of design. Happy peplum top is ready for you to grab the free. Greetings, I have completed 3 bikinis for my daughter and her friend. For small it would be ch13, ch16 for medium, and ch19 for a large. It Stretched a lot. I want a crochet bikini. Thin bikinis have been a favorite swimsuit model for the simple reason that they show the ultimate in skin. Crochet bikinis are still hot and not only for models, you can make a top with boyshorts or a bikini bottom with a top, …. RT if you agree:. This small crochet pattern is for a treat bag. Requirements: 4mm crochet hook, 6mm crochet hook, g of Double Knit cotton yarn, Waistband Elastic, darning needle Abbreviations: dtr double triple crochet, tr triple crochet, dc double crochet, sc single crochet, ch chain, sl st slip stitch, sp s space es , st s stitch es , beg beginning, rep repeat, sk skip Notes This skirt is worked onto waistband elastic that has been measured and sewn into a circle. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. What's your next crochet project going to be? He does not need a lot of thread and looks amazing on you.