Extraterritorial Criminal Jurisdiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abuse of Process in Cross-Border Cases: Moti V the Queen

ABUSE OF PROCESS IN CROSS-BORDER CASES: MOTI V THE QUEEN * DANIELLE IRELAND-PIPER In a majority of six to one, the High Court in Moti v The Queen concluded that the act of state doctrine does not preclude findings as to the legality of the conduct of a foreign government, where such a finding is determinative of an abuse of process. The decision is a welcome addition to existing international jurisprudence on due process rights in prosecutions of extraterritorial conduct. In turn, it is a reminder that operating extraterritorially does not mean operating without accountability. I INTRODUCTION In Moti v The Queen,1 the High Court of Australia considered whether proceedings can be maintained against a person who has not properly been brought within the jurisdiction by regular means, or whether such proceedings are an abuse of process. In so doing, a majority of six to one concluded that the act of state doctrine does not preclude findings as to the legality of the conduct of a foreign government, where those conclusions are a necessary step to determining a question within the competency of the court. This article will conclude the findings of the High Court in Moti v The Queen are a welcome addition to jurisprudence on procedural irregularities in the prosecution of transnational crime. The High Court in XYZ v Commonwealth2 confirmed that the Commonwealth may rely on section 51(xxix) of the Constitution of Australia to assert extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction over Australian citizens. Such assertions are also permitted under international law by virtue of the active nationality principle.3 However, although useful in fighting transnational crime, assertions of extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction are sometimes overly politicised, and vulnerable to abuses of process.4 Therefore, the decision in Moti v The Queen has implications for the prosecution of offences for conduct occurring extraterritorially, and is a timely reminder for state officials and prosecutors that operating extraterritorially does not mean operating without accountability. -

Participatory Approaches to Law and Justice Reform in Papua New Guinea

PACIFIC ISLANDS POLICY 3 Safety, Security, and Accessible Justice Participatory Approaches to Law and Justice Reform in Papua New Guinea ROSITA MACDONALD THE EAST-WEST CENTER is an education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and understanding among the peoples and nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center contributes to a peaceful, prosperous, and just Asia Pacific community by serving as a vigorous hub for cooperative research, education, and dialogue on critical issues of common concern to the Asia Pacific region and the United States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and the governments of the region. THE PACIFIC ISLANDS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM (PIDP) was established in 1980 as the research and training arm for the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders—a forum through which heads of government discuss critical policy issues with a wide range of interested countries, donors, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector representatives. PIDP activities are designed to assist Pacific Island leaders in advancing their collective efforts to achieve and sustain equitable social and economic development. As a regional organization working across the Pacific, the PIDP supports five major activity areas: (1) Secretariat of the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders, (2) Policy Research, (3) Education and Training, (4) Secretariat of the United States/Pacific Island Nations Joint Commercial Commis- sion, and (5) Pacific Islands Report (pireport.org). In support of the East-West Center’s mission to help build a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community, the PIDP serves as a catalyst for development and a link between the Pacific, the United States, and other countries. -

BTI 2010 | Papua New Guinea Country Report

BTI 2010 | Papua New Guinea Country Report Status Index 1-10 5.85 # 58 of 128 Democracy 1-10 6.35 # 50 of 128 Market Economy 1-10 5.36 # 70 of 128 Management Index 1-10 4.99 # 65 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Transformation Index (BTI) 2010. The BTI is a global ranking of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economic systems as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. The BTI is a joint project of the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Center for Applied Policy Research (C•A•P) at Munich University. More on the BTI at http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/ Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2010 — Papua New Guinea Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2009. © 2009 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2010 | Papua New Guinea 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 6.3 HDI 0.54 GDP p.c. $ 2084 Pop. growth % p.a. 2.0 HDI rank of 182 148 Gini Index 50.9 Life expectancy years 57 UN Education Index 0.52 Poverty2 % 57.4 Urban population % 12.6 Gender equality1 - Aid per capita $ 50.2 Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report 2009 | The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2009. Footnotes: (1) Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). (2) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary During the period under review, Papua New Guinea (PNG) made some progress toward providing its citizens greater freedom of choice by improving the state of democracy and its market-based economy. -

The Moti Affair in Papua New Guinea

SSGM WORKING PAPERS NUMBER 2007/1 THE MOTI AFFAIR IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA Hank Nelson Emeritus Professor, Department of Pacific and Asian History Visiting Fellow, SSGM ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University Paper written in August 2007 Author: Hank Nelson Year of Publication: 2007 Title: The Moti Affair in Papua New Guinea Series: State Society and Society in Melanesia Working Paper No. 2007/1 Publisher: State Society and Governance in Melanesia Program, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, Research School for Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University Place of Publication: Canberra State Society and Governance in Melanesia Program Working Papers The State Society and Governance in Melanesia Program Working Paper series seeks to provide readers with access to current research and analysis on contemporary issues on governance, state and society in Melanesia and the Pacific. Working Papers produced by the Program aim to facilitate discussion and debate in these areas; to link scholars working in different disciplines and regions; and engage the interest of policy communities. Disclaimer: The views expressed in publications on this website are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program. State Society and Governance in Melanesia Program Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Tel: +61 2 6125 8394 Fax: +61 2 6125 5525 Email: [email protected] State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program Working Paper 2007/1 2 The Moti Affair in Papua New Guinea Itself a minor matter in international affairs, the arrest, detention and escape of Julian Moti in Papua New Guinea revealed something of the relationships between three nations, the subsequent inquiry in Papua New Guinea provided evidence of the performance of institutions and elected and appointed officers, and the affair’s knock- on effects still reverberate. -

Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2006 Provided by Scholarspace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2006 provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Reviews of Papua New Guinea and functions to perform as stipulated in West Papua are not included in this Fiji’s 1997 Constitution. Perhaps the issue. sdl government assumed too much about people’s acceptance of the Fiji rule of law in a developing country By January 2006 the confl ict between or Third World context. As can be the Fiji Military Forces and the now gauged from Fiji’s coup culture since ousted government, which had been 1987, the causes of political confl ict led by the Soqosoqo Duavata ni in the country extend far beyond the Lewenivanua (sdl) party, had been scope of the modern rule of law, and continuing for almost fi ve years. One solutions involve additional political, of the main criticisms put forth by legal, and even customary measures. the commander of the Fiji Military Perhaps continued dialogue between Forces, Commodore Voreqe Baini- the sdl government and the Fiji marama, was that Laisenia Qarase’s Military Forces outside the param- government was lax in dealing with eters of Parliament could partially the 2000 coup perpetrators. A number have resolved Fiji’s ongoing political of high chiefs were allowed to serve crisis. After all, 95 percent of both the their prison terms extramurally, and sdl government and the Fiji Military one chiefl y parliamentarian returned Forces were indigenous Fijians. During to Parliament after his sentence. -

Pol It Ical Reviews • Melanesia

pol i t ical reviews • melanesia 597 to them (NC, 6–7 Oct, 12 Oct, 24 Oct that it could get only short-term con- 2006). tracts overseas (NC, 19 Dec 2006). After a month-long blockade, the david chappell police liberated Doniambo, but only two of its four ore sources upcoun- try were functioning. The rpcr and References ae traded barbs over alleged politi- Frogier, Pierre. 2006 Speech at rpcr cal plotting behind the strike, while Congress. 20 May. the cstnc adopted ustke’s tactic IHT, International Herald Tribune. Daily. of on-again, off-again picketing and Paris. http://www.iht.com blockages (NC, 14 Dec, 17 Oct, 20 Oct 2006). The cstnc even shut down the kol, Kanaky Online. http:// fr.groups local newspaper temporarily for what .yahoo.com / group / kanaky it considered unfair reporting (pir, 7 NC, Les Nouvelles-Calédoniennes. Daily. Nov 2006), while repeated negotia- Noumea. http://www.info.lnc.nc / tions stalled. Nea went to court for pir, Pacific Islands Report. his appeal of a conviction from the http://pidp.eastwestcenter.org / pireport previous year of blockades that had rnzi, Radio New Zealand International. condemned him to three months in http://www.rnzi.com prison. The judge upheld the convic- tion and sentence, but told Nea that TPM, Tahiti-Pacifique Magazine. Monthly. he could appeal to a higher court, and Papeete. that there would likely be a “more or less generous” amnesty granted after the 2007 presidential elections Solomon Islands for union-related offenses. By mid- November, Nea was softening his For Solomon Islands, 2006 brought general strike demands, was arrested a lot of expectations for positive for diverting sln funds and, with two change, especially with regard to associates, was fi ned us$20,000, and political leadership at the national soon was offering to resign from the level. -

Australia in the Rudd Era – Will Australia Engage More with PNG and the Pacific?

INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS Speech Series No. 16 Australia in the Rudd Era – Will Australia engage more with PNG and the Pacific? Sean Dorney March 2008 First published: March 2008 Published by: Institute of National Affairs PO Box 1530, Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea Copyright © 2008 Institute of National Affairs ISBN 9980-77-154-2 National Library Service – Papua New Guinea ii “Australia in the Rudd Era – Will Australia engage more with PNG and the Pacific?” A Public Address by Sean Dorney Pacific Correspondent ABC/Australia Network As part of Australia Week 2008 About a month ago, when Paul Barker and I were tossing around ideas for my subject matter tonight – he suggested a theme with some focus on PNG, Australia and their relationship. So I emailed him back, asking if I could keep it brief and simply get up and paraphrase what Kevin Rudd had just said in the Australian Parliament to the Stolen Generation – “Oh, look, all I want to say to the people of Papua New Guinea about our complex relationship is – Sorry, sorry, sorry!” And then I’d sit down? In fact, like a lot of you Paul, who does have a reasonable sense of humour, did not think that was appropriate or even funny. And, indeed, “Sorry” is not quite the right word. I don’t believe that we, non-Aboriginal Australians, need to be as apologetic to the people of this country as, perhaps, we need to be to the indigenous people of our own. After all, we opened up the ballot boxes to Papua New Guineans here in 1964 – a year before Aborigines were allowed to vote in Queensland State elections and three years before Aborigines were even permitted to be included in the Australian census. -

Australia's Arc of Instability: Evolution, Causes and Policy Dilemmas

The Otemon Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 32, pp. 37−59, 2006 37 Australia’s Arc of Instability: Evolution, Causes and Policy Dilemmas Dennis Rumley University of Western Australia Introduction At the end of the Cold War period, the geopolitics ofAustralia’s regional relations were de- scribed in terms of the application of a ‘directional front model’ ― that is, it was argued that, dur- ing the late-Cold War and post-Cold War periods, Australia’s regional relations had been developed along four broad ‘fronts’ (Rumley, 1999). A cooperative security front was developed to Austra- lia’s north; an aid front was in place to Australia’s east; an environmental security front had been agreed to Australia’s south; and, in 1997, a trade front was constructed to Australia’s west (Figure 1). These four fronts had been developed primarily for reasons of regional security, in the broadest meaning of the multidimensional term security. The most recent creation of the fourth (Indian Ocean) front can also be represented as a ‘closing’ of the circle of security around Australia. The end result was that Australia had attempted to construct a geopolitical foundation for a secure re- Figure 1 Regions of Australian Strategic Interest (Source: Rumley, 1999, p. 169) 38 Australia’s Arc of Instability gional future. However, to some extent, this construction has been jeopardized by the increasing in- cidence of non-traditional security threats, especially after 9/11 and 12/10, and the emergence of a so-called ‘arc of instability’ located within Australia’s region of primary strategic interest or ROPSI (Figure 1). -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews The Region in Review: International Issues and Events, 2011 nic maclellan Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2011 david chappell, jon fraenkel, gordon leua nanau, howard van trease, muridan s widjojo The Contemporary Pacic, Volume 24, Number 2, 359–431 © 2012 by University of Hawai‘i Press 359 Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2011 Review of Papua New Guinea not top-level schisms. Two of the most included in this issue. senior officers in the Republic of Fiji Military Forces—Land Forces Com- Fiji mander Brigadier General Pita Driti The year 2011 was the first since the and Third Battalion, Fiji Infantry December 2006 coup to occur with- Regiment Commander Roko Tevita out a major political crisis in Fiji. In Uluilakeba Mara—had been, without every previous year, the regime faced official explanation, told to use up stiff tests that potentially threatened outstanding leave in October 2010. its very survival: public sector strikes In February 2011, they were replaced in 2007, the rupture with Mahendra in their substantive positions, respec- Chaudhry’s Fiji Labour Party in 2008, tively, by Colonel Mosese Tikoitoga a ruling on the unconstitutionality of and Lieutenant Colonel Jone Logavatu the government followed by the abro- Kalouniwai. Tevita Mara, the young- gation of the constitution in 2009, est son of the late Ratu Sir Kamisese and schisms among the military top Mara, Fiji’s former president, had command in late 2010. By contrast, until 2008 been a strong backer of 2011 passed without major domestic the 2006 coup and a loyal ally of challenges, although harassment of Bainimarama. -

State Building Or State Transformation? Risk Management at the Fringes of the Global Order

STATE BUILDING OR STATE TRANSFORMATION? RISK MANAGEMENT AT THE FRINGES OF THE GLOBAL ORDER SHAHAR HAMEIRI BA (HONOURS) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2009 Abstract This thesis develops a new framework for explaining the effects and possible trajectories of state building interventions (SBIs). This is for both examining specific interventions and learning about the precise nature of the post-Cold War global order – how power is distributed, exercised, constrained and challenged within and between states. In the post-Cold War years, but particularly since the September 11 2001 terrorist attacks, so-called failed states have become a central security concern for policymakers. In tandem, there has been an influx of practitioner and scholarly interest in international ‘state building’. Prevalent approaches to state building are premised on a static conception of the state and therefore seek to evaluate SBIs in terms of whether they help create ‘more’ or ‘less’ state. In contrast, this thesis examines SBIs as a new mode of governance in the global political economy that is transformative of both intervened and intervening states, leading to the creation of a transnationalising and transnationally regulated form of statehood. Based on a conception of the state as a site of social and political struggle this study examines the ways in which SBIs affect the distribution, production and reproduction of political power in intervened states: Who rules and how? What social and political conflicts are engendered or exacerbated by SBIs, and how are they managed? What alliances and coalitions support the production/reproduction of power relationships associated with SBIs? The thesis provides a conceptual framework for understanding the complex governance terrain SBIs open up. -

Elites and the Modern State in Papua New Guinea And

ELITES AND THE MODERN STATE IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA AND SOLOMON ISLANDS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science by Andrew James Beaufort Department of Political Science, University of Canterbury 2012 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................ 1 List of Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Introducing the Research .................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Defining the Elites ........................................................................................................... 7 1.3 The Role of Elites in PNG and Solomon Islands ............................................................. 9 1.3.1 Political Elites ............................................................................................................ 9 1.3.2 Religious Elites ........................................................................................................ 16 1.4 Research Method .......................................................................................................... -

Questionaire to Australian Federal DPP Bugg QC 07 08 07

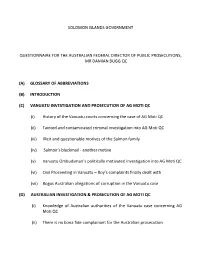

SOLOMON ISLANDS GOVERNMENT QUESTIONNAIRE FOR THE AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS, MR DAMIAN BUGG QC (A) GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS (B) INTRODUCTION (C) VANUATU INVESTIGATION AND PROSECUTION OF AG MOTI QC (i) History of the Vanuatu courts concerning the case of AG Moti QC (ii) Tainted and contaminated criminal investigation into AG Moti QC (iii) Illicit and questionable motives of the Salmon family (iv) Salmon’s blackmail - another motive (v) Vanuatu Ombudsman’s Politically motivated investigation into AG Moti QC (vi) Civil Proceeding in Vanuatu – Roy’s comPlaints finally dealt with (vii) Bogus Australian allegations of corruPtion in the Vanuatu case (D) AUSTRALIAN INVESTIGATION & PROSECUTION OF AG MOTI QC (i) Knowledge of Australian authorities of the Vanuatu case concerning AG Moti QC (ii) There is no bona fide comPlainant for the Australian Prosecution (iii) Australian Prosecution of AG Moti QC is a violation of the double jeoPardy principle (iv) Unexplained delay in the Australian criminal investigation – sPurious excuses (v) Prejudicial and oPPressive delay – AG Moti QC would not receive a fair trial in Australia (vi) Prejudicial Publicity – AG Moti QC would not receive a fair trial in Australia (vii) Prejudice and oPPression – it would be unfair for AG Moti QC to be tried in Australia (viii) Australia’s Political agenda in the case of AG Moti QC (ix) Australia’s investigation of AG Moti QC– a Politically driven case (x) AG Moti QC is not a fugitive from justice of India in relation to the Australian arrest warrant