Edexcel a Level Aos3: Music for Film, Part 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday Morning, July 9

MONDAY MORNING, JULY 9 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Dr. Oz and Terry Wrong; Live! With Kelly Kyra Sedgwick; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Aaron Paul. (N) (TV14) Eric McCormack. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Ray Romano; Piper Perabo. (N) (cc) Anderson Tom Bergeron; Bethen- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) ny Frankel. (cc) (TVG) Power Yoga: Mind Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Big Bird wants to Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 and Body (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) change his appearance. (TVY) Kid (cc) (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Miss- 12/KPTV 12 12 ing bookkeeper. (cc) (TV14) Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Feed the Children Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Northwest Focus Always Good Manna From Behind the Jewish Voice (cc) Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) News (cc) Heaven (cc) Scenes (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TVPG) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (cc) (TVPG) America Now (cc) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (cc) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVG) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Criminal Minds Soul Mates. -

Mustang Daily, November 3, 1967

i r a f c i T * ; CALIFORNIA SlATt mmmic mm VOL. XXX, NO. 15 SAN LUIS OBISPO, CALIFORNIA FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 1067 --------------------------------------- r- ■ Season tickets: Individualism the keynote campus bargain One of thii best bargain* on Swinging septet to sing cninpiii* is overlooked by niuny students. ’ • •’ v - ‘ For Jfl rartntudont muy pur chase a season ticket admitting him to six plays at the I.ittlc at upcoming concert Theater, That,is only 12 apt! nne.- Imlf cents per play for an even- If namoa promise anything, the Thursday; and by the following term contract with In Arts Re iliu’a entertaiiimonL college is in for a "good time." Monday, they were signed -to a cords. Two plays are presented each The Good Time Singers of the contract by NBC-TV to appear What has made the Good Time ipiurter. Today and -tommorrow Andy Williams Television Shbw, us regular* on The Andy Wil Singers the success that they "Spoon River Anthology" is being will appear in concert at 8 p.nt., liams Show. areT The quaation wait'posed to produced and on Nov. 1(1-18 Saturday, Nov. 11 in the Men1* In one week the talented seven Lee Montgomery, leader of tho "Draeula" will be presented. Pleys Gym. (Five boys and two girla) found group. "Although we’re atl pert begin at 8:80 p.m. ' Tickets are now on sale at the themselves In a position.that most a t one group," Lee answered, Season tickets are 'also avail ASI office. Student tickets are groups fail to achieve in a life “that doesn't mean we all have to able to tho general public fur 81.80 for bleachers, "11.78 for re time. -

The Other, Other, Other All-Batman Game by Mike Young Intercon H in Chelmsford, Mass

The Other, Other, Other All-Batman Game By Mike Young Intercon H in Chelmsford, Mass. It was 6:00 on a Friday. I had just finished bragging that I wasn't running anything this weekend. Phillip Kelley dares me to write a game for the con. At 6:30 we all sit down to play The Other, Other, OtherAll Batman Game. Curse you, Phil Kelley! You can read an excellent history of The All Batman Game, The Other All Batman Game, and The Other, Other All-Batman Game at Phil’s site. I believe that mine is unique in being the only one in which all the characters are actually Batman, well more or less. Thanks to the players of the inaugural run: Daniel Abraham, Vivian Abraham, Dave Cave, Quinn D, Greer Hauptman, Phillip Kelley, Sue Lee, David Lichtenstein, and Drew Novick. Game Situation A group of omnipotent, plot driven entities known as the Omniseers have kidnapped a number of Batmen from across time and space and forced them to choose one to be the true Batman. The Batmen may choose any one of them to be the true one, but they won't. They will dither and argue and fight. After ten or so minutes, or when the joke has run out, just pick one randomly. Game Set Up Print out the character sheets below and distribute them to the players. The combat system can be any of the following, or just make up your own. The winner can do whatever they want to the loser. Potential Combat Systems: MENKS: Players get cards equal to their Power Level. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Talisman: Batman™ Super-Villains Edition Rules

INTRODUCTION Key Components and The object of the game is to sneak, fight and search your way through Arkham Asylum, and be the first of the Concepts Overview Villains to reach the Security Control Room at the top of This section will introduce new players to the key concepts the Guard Tower. Once there you must subdue Batman and components of Talisman. For players who are familiar and turn off all security systems. The first player to do with Batman Talisman, or the original Talisman game, we this will free all of the Villains and become the leader of recommend jumping ahead to ‘Game Set-up’ on page 6. Gotham City’s underworld, and will win the game. In order to reach the end, you’ll need to collect various Items, gain Followers and improve your Strength and Cunning. Game Board Most importantly, you will need to locate a Security Key Card The game board depicts the Villains’ hand drawn maps of to unlock the Security Control Room. Without one of these Arkham Asylum. It is divided into three Regions: First Floor powerful cards there is no hope of completing your task. (Outer Region), Second Floor (Middle Region), and Tower (Inner Region). Number of Players Up to six players can play Batman Talisman, but the more players that are participating, the longer the game will last. For this reason we suggest using the following rules for faster play. If you have fewer players, or would like to experience the traditional longer Talisman game there are alternative rules provided at the end of this rulebook on page 14. -

Thesis Vol.2 5:23:18

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Performance of Play Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rj918rh Author Jones, Lauren Brianna Publication Date 2018 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rj918rh#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Performance of Play, Lauren Jones A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Music by Lauren Jones Committee in charge: Professor Susan Narucki, Chair Professor Sarah Hankins Professor Stephanie Richards 2018 The Thesis of Lauren Jones is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………iv List of Supplemental Videos………………………………………………………………………v Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………….vi Epigraph………………………………………………………………………………………… vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………………...viii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Play as a Creative State……………………………………………………………………………4 Pee-wee’s Playhouse: A Performance of Play………………………………………………….. 11 Pocket Music………………….……………………………………………………………….....17 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 References…………………………………………………………………………………...…...23 iv LIST OF SUPPLEMENTAL VIDEOS jones_01_bossy_screen.wav -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/2/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

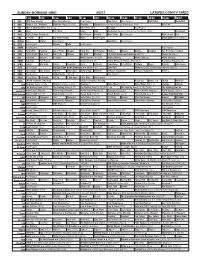

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/2/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Raw Travel Paid Program Bull Riding Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Pregame Hockey Boston Bruins at Chicago Blackhawks. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News NBA Basketball Boston Celtics at New York Knicks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program Dead Again ››› (1991) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Fun N’ Simple Cooking 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 Å Vibrant for Life Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar In the Wind. White Collar Å White Collar Å White Collar Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs ›› (2009) (PG) Zona NBA Killers › (2010, Acción) Ashton Kutcher. -

Star Wars Episode Tunes: Live Performances Attack on the Score Around the Globe

v7n4cov 5/31/02 11:44 AM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV VOLUME 7, NUMBER 4 TV Music page 10 SUMMER MOVIESHOWDOWN THEAMAZING ELF-MAN Our friendly neighborhood super-scorer ATTACK ON THE CLONES John Williams’ score goes BOOM! LEGEND-ARY GOLDSMITH The lost fantasy returns on DVD ARTISTIC DEVOLUTION The indie life of Mark Mothersbaugh PLUS Lots of the latest CDs reviewed 04> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v7n4cov 5/31/02 11:44 AM Page c2 The Symphony had almost no budget to design and produce a newsletter, but we thought it was important to publish one for subscribers and donors. Joe set up an attractive, versatile template for us and provided basic trainingFSMCD in Vol. Quark 5, No.and 7newsletter • Golden designAge Classics so that now we're able to produce a quarterly newsletter in-house.We get lots of compliments on our newsletter,On The and we Beach/The love having the tools Secret to do it ourselves. of Santa Vittoria by Ernest Gold FSM presents a film composer gravely unrepresented on CD with a doubleheader by Ernest Gold: On the Beach (1959) and The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969), both films directed by Stanley Kramer, with whom Gold shared his most fruitful collaboration. On the Beach is an “event” picture dealing with the deadly aftermath of a nuclear war: Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Anthony Perkins and Fred Astaire star as among the last survivors of humanity, waiting for a radioactive cloud to engulf them on the Southern coast of Australia. -

This List Attempts to Document Every Vinyl Record Released in the USA, Only, Relating to the Batman Craze of the 1960’S

This list attempts to document every vinyl record released in the USA, only, relating to the Batman craze of the 1960’s. US 7”/Singles: Artist – “Title” A-Side / “Title” B-Side (Mfg’r Record #, Date) (Notes) · 4 Of Us - “Batman” / “You Gonna Be Mine” (Hideout 1003, 1965) (A surf instrumental and is not related to the TV series; later pressings of this single have the Batman song retitled as “Freefall”) · 5th Avenue Busses - “Robin Boy Wonder” / “Fantastic Voyage” (20th Century Fox 45-6653, 1966) (Promo copy exists) · The Airmen Of Note – “Theme From Batman” / “Second Time Around” (The United States Airforce Public Service Program” GZS 108695, 1966?) (“Music In the Air” radio transcription 33 1/3 RPM, 7” single, Programs NR: 423/424. Label reads “This record is the property of the U.S. Government and cannot be used for commercial purposes.” The Airmen Of Note are the jazz ensemble within the US Army Air Forces Band and was formed to carry on the music of The Major Glenn Miller Army Air Forces Orchestra.) · Davie Allan & The Arrows - “Batman Theme” (Reportedly recorded in 1966 but never issued as 45. Instead, it first appeared on the 1996 reissue CD of the Various Artists “Wild Angels” soundtrack.) · Astronauts - “Batman Theme” (Never issued as 45. A surf instrumental first released on 1963 LP so is not TV show influenced) · Avengers - “The Batman Theme” / “Back Side Blues” (MGM K 13465, 1966) (Though released as by "The Avengers," the A-side was recorded by all-female group The Robins, while the flip was recorded by popular Ardent recording -

Diagnostic and Prognostic Computed Tomography Imaging Markers in Basilar Artery Occlusion (Review)

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 22: 954, 2021 Diagnostic and prognostic computed tomography imaging markers in basilar artery occlusion (Review) RARES CRISTIAN FILEP1, LUCIAN MARGINEAN1, ADINA STOIAN2 and ZOLTAN BAJKO3 1PhD School of Medicine, and Departments of 2Pathophysiology and 3Neurology, ‘George Emil Palade’ University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology, 540142 Târgu Mureș, Romania Received May 5, 2021; Accepted June 4, 2021 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10386 Abstract. Acute ischemic stroke treatment has been revolution‑ in the last decade. Hyperdense Basilar Artery Sign (HDBA), ized by the addition of mechanical and aspiration thrombectomy. Posterior Circulations‑Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Randomized controlled trials have proven beyond doubt, the Score (pc‑ASPECTS), Pons‑Midbrain Index (PMI), Posterior substantial clinical impact of endovascular interventions in ante‑ Circulation Collateral Score (pc‑CS), Posterior Circulation rior circulation territory strokes. Unfortunately, patients with CT Angiography Score (pc‑CTA), and Basilar Artery on CT vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke could not be included in these Prognostic Score (BATMAN), are computed tomography (CT) early trials due to inherent clinical, radiological, and prognostic markers with properties that can aid the diagnosis of BAO and particularities of posterior circulation ischemia; thus, indications can independently predict clinical outcome. This paper aims to for the treatment of posterior fossa strokes and basilar artery present a comprehensive review of these imaging signs to have occlusion (BAO) are mainly based on retrospective studies and a thorough understanding of their diagnostic and prognostic registries. BAO carries high morbidity and mortality, despite attributes. the new improvements in endovascular therapy. Identifying patients who will likely benefit from invasive treatment and have a good clinical outcome resides in discovering clinical, Contents biological, or imaging markers, that have prognostic implica‑ tions. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham.