Thesis Vol.2 5:23:18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday Morning, July 9

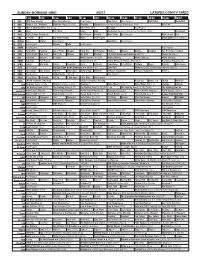

MONDAY MORNING, JULY 9 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Dr. Oz and Terry Wrong; Live! With Kelly Kyra Sedgwick; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Aaron Paul. (N) (TV14) Eric McCormack. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Ray Romano; Piper Perabo. (N) (cc) Anderson Tom Bergeron; Bethen- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) ny Frankel. (cc) (TVG) Power Yoga: Mind Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Big Bird wants to Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 and Body (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) change his appearance. (TVY) Kid (cc) (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Miss- 12/KPTV 12 12 ing bookkeeper. (cc) (TV14) Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Feed the Children Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Northwest Focus Always Good Manna From Behind the Jewish Voice (cc) Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) News (cc) Heaven (cc) Scenes (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TVPG) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (cc) (TVPG) America Now (cc) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (cc) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVG) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Criminal Minds Soul Mates. -

Bridesmaids”: a Modern Response to Patriarchy

“Bridesmaids”: A Modern Response to Patriarchy A Senior Project presented to The Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Blair Buckley © 2013 Blair Buckley Buckley 2 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................... 3 Bridesmaids : The Film....................................................................... 6 Rhetorical Methods............................................................................. 9 Critiquing the Artifact....................................................................... 14 Findings and Implications................................................................. 19 Areas for Future Study...................................................................... 22 Works Cited...................................................................................... 24 Buckley 3 Bridesmaids : A Modern Response to Patriarchy Introduction We see implications of our patriarchal world stamped across our society, not only in our actions, but in the endless artifacts to which we are exposed on both a conscious and subconscious basis. One outlet which constantly both reflects and enables patriarchy is our media; the movie industry in particular plays a critical role in constructing gender roles and reflecting our cultural attitudes toward patriarchy. Film and sociology scholars Stacie Furia and Denise Beilby say, -

Shaun Boylan

Shaun Boylan Los Angeles, CA Height: 6”4’ | Weight: 215 lbs | Hair color: brown | Eye Color: blue FILM THE END Supporting Dir. Anthony Jerjen THIS IS HOW YOU DIE Supporting Dir. Michael Mohan SPRAYED Supporting Dir. Jacqueline Richards PARAMECIUM PETE Lead Dir. Kathryn Fuss THE BEST MAN Supporting Dir. Justin Lazernik TELEVISION/WEB THAT’S WHAT SHE SAID Guest Star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder EAGLES FANS Guest Star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder THE MAN WHO CREATED THE EMOJI Co-star Dir. Ryan Kelly & Andrew Heder OPEN HOUSE Guest Star Dir. Erin Hees SURPRIZE TEAM Series Regular Dir. Russell Ford CO-WORKERS Guest Star Dir. Nick Corirossi COMMERCIAL MAKESPACE Principal Dir. Gaelan Draper DORITOS Principal Dir. Andrew Adams SHARPIE Principal Dir. Danny Foxx POWERING CALIFORNIA Voiceover Dir. Trent Stockton POWERING CALIFORNIA Host Dir. Trent Stockton IMPROV/SKETCH SECOND CITY Hollywood, CA Undateable IMPROV OLYMPIC Chicago, IL Improv Graduate WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Mission Improvable WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Bear Supply WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA Cobranauts WESTSIDE COMEDY THEATER Santa Monica, CA The Diary Show SF SKETCHFEST San Francisco, CA Festival Show L.A. IMPROV FESTIVAL Hollywood, CA Festival show JUST THE FUNNY Miami, FL Festival show LAS VEGAS IMPROV FESTIVAL Las Vegas, NV Festival Show TRAINING Lesly Kahn Los Angeles, CA Work Session The Groundlings Hollywood, CA Improv - Core Track Second City Hollywood, CA Conservatory Program iO (Improv Olympic) Chicago, IL Improv Graduate M.I.’s Westside Comedy Theater Santa Monica, CA Instructor/Improv Graduate AK Studios LA Los Angeles, CA Acting/Commercial Workshops SPECIAL SKILLS Voice and Speech - English, Russian, Mexican Spanish and German accents; various impressions Weaponry - Glock 17 (on-set) Athletics - Basketball, Soccer, Frisbee, Volleyball and Cycling; Licensed driver . -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/2/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/2/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Raw Travel Paid Program Bull Riding Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Pregame Hockey Boston Bruins at Chicago Blackhawks. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News NBA Basketball Boston Celtics at New York Knicks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program Dead Again ››› (1991) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Fun N’ Simple Cooking 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 Å Vibrant for Life Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar In the Wind. White Collar Å White Collar Å White Collar Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs ›› (2009) (PG) Zona NBA Killers › (2010, Acción) Ashton Kutcher. -

For Our First-Ever Women in Comedy Issue, We Bring You Wit, Wisdom

Women in Comedy For our first-ever Women in THE GLORIOUS MS. RUDOLPH The character we’ve yet to see: “I’ve always Comedy Issue, we bring ON HER IMITATION GAME wanted to do Gwen Stefani. I did her over the For seven seasons on Saturday Night Live, years at The Groundlings, and I played in a you wit, wisdom, and war Maya Rudolph carried sketch after sketch band—we even played some shows with No stories from some of the with her over-the-top but somehow totally Doubt!—so I came up with an impression of world’s most hilarious women dead-on impressions—Donatella Versace, her, but there was never a reason to do her on —Maya Rudolph, Mindy Beyoncé, and Oprah among them. Now, with SNL. It’s all about the voice.” Her fondest Maya & Marty in Manhattan, the hour-long miss: “I was asked to come back to SNL Kaling, Sarah Silverman, NBC variety show she cohosts with Martin and play Barack Obama when he was Chelsea Handler, and more. Short, Rudolph is back in the live format running. I had no take on him whatsoever. Plus: our 100-comedian survey! she knows best, delighting audiences with I just couldn’t figure out the voice. At dress guest star–laden skits, song and dance, and, rehearsal, I was in this little Brooks Brothers of course, her homage-style mimicry that suit and my Scott Joplin wig, and Barack never makes any one celebrity the butt of came up behind me. I turned to him and said, a joke. -

{PDF EPUB} Elvira Mistress of the Dark a Photographic Retrospective of the Queen of Halloween by Cassandra Pete the Untold Truth of Elvira

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Elvira Mistress of the Dark A Photographic Retrospective of the Queen of Halloween by Cassandra Pete The Untold Truth Of Elvira. There are some public figures who seem to have always been around, people everyone knows even if they are not familiar with their body of work. B-movie horror show hostess and scream queen Elvira is one such entity, instantly recognizable with her enormous black bouffant hairstyle and gratuitous cleavage accented by the plunging neckline of her skin-tight vampiress gown. But behind the vamp-camp drag image is a woman with a storied history, one that often takes a backseat to her biggest claim to fame. From her birth in Kansas in 1951, to her first stint as horror hostess on Movie Macabre , to her present-day fame as television, movie, comic book, and merchandise star, Cassandra Peterson seems to be consistently growing and building her image. As she continues to work well into her sixties, still as simultaneously campy and glamorous as ever, her fascinating history deserves a deeper dive. Marked by fate to become Elvira. Many people with a penchant for the paranormal grow the fascination early on, their interests not aligning with those of their peers, marking them as an outsider. It was no different for a young Cassandra Peterson. As a very young child, she suffered scalding burns over 35% of her body that resulted in her needing to have a host of skin graft surgeries. This incident later caused her to feel marked, both physically and otherwise, as different, and began her fascination with monsters and outcasts. -

Edexcel a Level Aos3: Music for Film, Part 3

KSKS55 Edexcel A level AoS3: Music for film, part 3 James Manwaring by James Manwaring is Director of Music for Windsor Learning Partnership, and has been teaching music for 13 years. He is a member INTRODUCTION of the MMA and ISM, and he writes This is the last of three resources on film music (following part one inMusic Teacher, November 2017, and part a music education two in January 2018) based around Edexcel’s Area of Study 3. Here we’ll focus on Batman Returns, and also blog. some further ways into film music composition for A level students. STARTING POINT: COMPOSITION Film music is a popular genre among students. They enjoy both the set works and the wider listening. Composing in a cinematic genre also remains a popular avenue for many students, who enjoy crafting and creating music that tells a clear story. In this resource, I want to start by looking at some specific ways into film composition, so that students can create music that fits in with the set works. If students are going to truly understand a genre of music, they need to engage fully with it. Composing cinematic music is a great way for students to understand cinematic music – and that goes for all genres of music, in fact. Performance is also important, however: students should have the chance to play music from different genres – and there are some great arrangements out there for all abilities. If you can play something cinematic in your orchestra, wind band or brass band, it will really bring the music to life. -

The Laugh Track Justin Kendall Iowa State University

Volume 53 Issue 1 Article 9 October 2001 The Laugh Track Justin Kendall Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos Recommended Citation Kendall, Justin (2001) "The Laugh Track," Ethos: Vol. 2002 , Article 9. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos/vol2002/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ethos by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Story by Justin Kendall "Because the Midwest isn't always a hot spot for entertainment or 'big city life' we have to create our own fun, which is always the best kind. Also, I think Midwesterners are humble and polite, which makes for some great self-deprecating humor." - Carrie Seim "Because the Midwest isn't always a hot spot for through his wavy, dark mane. His right hand entertainment or 'big-city life,' we have to create is fixed chest-high, clutching rhe mic. His tan, our own fun, which is always the best kind. Also, moon-shaped face contorts inro various exag I think Midwesterners are humble and polite, gerated and animated expressions. His eyes which makes for some great self-deprecating bulge. humor. "- Carrie Seim "I was reading the Daily, so I know a little bit about what's going on now," he begins. "I was "People from the Midwest have a very wry, sar busy just before rhe show fabricating my sexu donic sense ofhumor, different from a lot ofpeo al ass a ulr." ple I've encountered in California. -

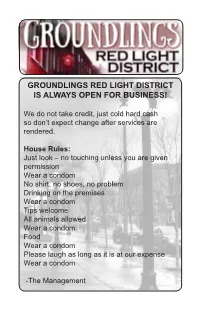

Groundlings Red Light District Is Always Open for Business!

GROUNDLINGS RED LIGHT DISTRICT IS ALWAYS OPEN FOR BUSINESS! We do not take credit, just cold hard cash so don’t expect change after services are rendered. House Rules: Just look – no touching unless you are given permission Wear a condom No shirt, no shoes, no problem Drinking on the premises Wear a condom Tips welcome All animals allowed Wear a condom Food Wear a condom Please laugh as long as it is at our expense Wear a condom -The Management KAREN MARUYAMA is having a blast directing the Main show again. She is a Main company alum who enjoys teaching here and at the American Film Institute. She also directs the acclaimed show The Black Version at the Largo Theater. She appeared in the films THE CAMPAIGN, THE BUCKET LIST and PULP FICTION. Her television credits include 2 BROKE GIRLS, ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT, NIP/TUCK, GHOST WHISPERER and has lent her voice to THE SIMPSONS, FUTURAMA, Karen AMERICAN DAD and FAMILY GUY. Maruyama (Director) Scott Beehner’s television appearances include CASUAL, EXTANT, NCIS, MODERN FAMILY, WORKAHOLICS, IT’S ALWAYS SUNNY IN PHILADELPHIA, HART OF DIXIE, SUPER FUN NIGHT, UP ALL NIGHT, PERFECT COUPLES, MAD LOVE, WORST WEEK, ZEKE & LUTHER, THUNDERMANS and THE YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS. Film credits include GANGSTER SQUAD, Woody Allen’s SWEET AND LOWDOWN, Whit Stillman’s THE LAST DAYS OF DISCO and TOMCATS. Originally from Omaha, Nebraska, Scott is a graduate of Scott Fordham University in New York City and the Actors Studio MFA Program. Beehner Timothy played Jack Flynn the head of GM on MAD MEN. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

Ks5101-20101019.Pdf

SHE’S BACK! PGEA 8 KENNESAW STATE UNIVERSITY THESENTINEL TU ESDAY, OCT. 19, 2010 VOL. 46 ISSUE 9 SINCE 1966 WWW.KSUSENTINEL.COM KENNESAW, GA AIDS: The forgotten pandemic Student passes away due by James Swift to massive head injuries CULTURE EDItoR Carolyn Grindrod By the time Tricia Grin- NEWS EDItoR del was 35, she had attended KSU Senior Michael Chadwick “Chad” Wilson, 24, of Cairo, Ga. more funerals and memorial died on Oct. 12 at an Atlanta hospital after undergoing surgery services than her parents had for head injuries after an accident the prior day. attended in their lifetimes. According to Cobb County police, Wilson was found in the Death was part of her job morning hours of Oct. 11 near the intersection of Kennestone as a director for the nonprofit Circle and Cobb Parkway with massive head trauma. He was then AID Atlanta Inc., a job she left taken by Lifeflight to Atlanta Medical Center where he died at in 1993. Grindel has been a 12:30 p.m. the next day. communication instructor at Cobb County Police Information Officer Sgt. Dana Pierce said KSU since 2002. no other bodily trauma was found. Cobb County’s Crimes Against According to a 2009 World Persons unit is still investigating the incident. Health Organization report, Wilson graduated with honors from Cairo High School in 2004 an estimated 25 million people and attended Bainbridge College in Bainbridge, Ga. He trans- worldwide have died from ferred to KSU in 2006 as an art major with a concentration in AIDS, and an estimated 33.4 graphic communication and design.