By Vern Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

The Johnsonian October 24, 1941

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University The oJ hnsonian 1940-1949 The oJ hnsonian 10-24-1941 The ohnsoniJ an October 24, 1941 Winthrop University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian1940s Recommended Citation Winthrop University, "The oJ hnsonian October 24, 1941" (1941). The Johnsonian 1940-1949. 24. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/thejohnsonian1940s/24 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The oJ hnsonian at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oJ hnsonian 1940-1949 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •a OUR CUEED: It's better to tit on the The Johnsonian wants to deserve • rep- utation for accuracy, thoroughness, and tide than to stay i fairness in the covering of the Winthrop campus. You will do us a favor to call our school and sit. attention to any failure in measuring up to any of these fundamentals of good news- papering. The onian THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF WINTHROP COLLEGE VOLUME XIX ROCK HILL, SOUTH CAROLINA, OCTOBER 24, 1M1 Masquers Press Club These On Campus Next Week Campus To Hear 2 Artist Groups To Give 4 Names Head Next Week; Dr. W. P. Jacobs Here Fanny Cowan Chosen yrtf * One-Acts Chairman; 10 Init- ' > iated Monday a#- For Assembly; Sockman Praised Nov. 14 Date Set For Fanny Cowan, senior from Fall Performance; Tamassce, was named chair- man of the Press club at the New York Author-Minister Urges The Salzedo List Play Com- initiation meeting Monday Presbyterian mittee* night in the Tatler office. -

Watch-Rhine.Pdf

RCC THEARE presents by Lillian Hellman Cast List (in order of appearance) Anise .................................................................. Rey Alexis Joseph .........................................................Khari Butler II Fanny Farrelly ........................... Kelsey Sue Klocksieben David Farrelly ............................................Dakota Daigle Marth de Brancovis ..............................Annamarie Davis Teck de Brancovis ..........................................Byron Clark Sara Muller ............................................Camerina Roman Joshua Muller .............................................Nicholas Diaz Bodo Muller ............................................... Jesse Nganga Babette Muller ...........................................Cristal Corona Kurt Muller ...................................................... Justin Starr Director Chance Dean Stage Manager ASM/Property Master Jordyn Neiblas Sidney Paulido Set Designer Lighting Designer Technical Director Todd Faux Jason Graham Raymond Couture Original Music composed by Rey Alexis Watch on the Rhine is presented by special arrangment with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York OPENING NIGHT MAY 14, 2021 AVAILABLE MAY 15 & 16 WITH BROADWAY ON DEMAND THE PLAY An Anti-Fascist German engineer, his American-born wife, rising Nazi threat. In the sanctuary of American soil, an and their three children, return to the United States in unscrupulous Nazi sympathizer discovers their secret and 1940 after engaging in underground resistance to the threatens -

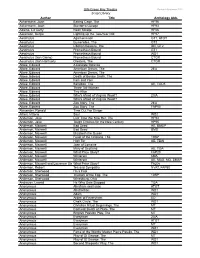

UW-Green Bay Theatre Script Library

UW-Green Bay Theatre Revised: November 2012 Script Library Author Title Anthology Abb. Ackermann, Joan Batting Cage, The HF96 Ackermann, Joan Stanton's Garage HF93 Adams, Liz Duffy Neon Mirage HF06 Aerenson, Benjie Lighting up the Two-Year Old HF97 Aeschylus Agamenmnon GT1, ATOT Aeschylus Eumenides, The GT3 Aeschylus Libation Bearers, The DD, GT2 Aeschylus Prometheus Bound GT1 Aeschylus Prometheus Bound WD1 Aeschylus (tran Grene) Prometheus Bound CTGR Aeschylus (tran Harrison) Oresteia, The CTGR Albee, Edward A Delicate Balance Albee, Edward American Dream, The 2EA Albee, Edward American Dream, The Albee, Edward Death of Bessie Smith, The Albee, Edward Fam and Yam Albee, Edward Sandbox, The AE, TOD5 Albee, Edward Three Tall Women Albee, Edward Tiny Alice Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? 23IA Albee, Edward Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee, Edward Zoo Story, The 2EA Albee, Edward Zoo Story, The FAP50 Alexander, Ronald Time Out For Ginger Alfieri, Vittorio Saul WD2 Anderson, Jane Last Time We Saw Her, The HF94 Anderson, Jane Tough Choices for the New Century HF95 Anderson, Maxwell Bad Seed AE, BMSP Anderson, Maxwell Bad Seed BMS Anderson, Maxwell Elizabeth the Queen Anderson, Maxwell Feast of the Ortolans, The 10SP Anderson, Maxwell High Tor AE, TDAI Anderson, Maxwell Joan of Lorraine Anderson, Maxwell Mary of Scotland AE, TGA Anderson, Maxwell What Price Glory? FAP20 Anderson, Maxwell Winterset 6MA Anderson, Maxwell Winterset AE, MAD, MD, SMAP Anderson, Maxwell and Laurence StallingsWhat Price Glory? FA20s Anderson, Robert -

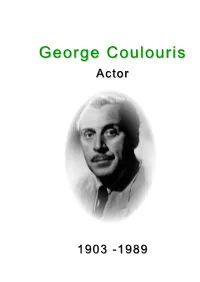

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right. -

2016/17 Season

2016/17 SEASON WATCH ON THE RHINE TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Director 7 Director’s Note 9 Title Page 11 Time and Place / Cast List / For This Production 13 Bios - Cast 15 Bios - Creative Team 19 Arena Stage Leadership ARENA STAGE 20 Board of Trustees / Next Stage / Theatre Forward 1101 Sixth Street SW Washington, DC 20024-2461 21 Thank You – The Annual Fund ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 24 Full Circle Society arenastage.org © 2017 Arena Stage. 25 Thank You – Institutional Donors All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and must not be reproduced in any manner without 26 Theater Staff written permission. Watch on the Rhine Program Book Published February 3, 2017 Cover Illustration by Paul Rogers Program Book Staff Anna Russell, Director of Publications David Sunshine, Graphic Designer 2016/17 SEASON 3 ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING Lillian Hellman was independent, outspoken, headstrong, brave, difficult and politically active. She was called a genius and a liar and was not one to shy away from bold political views. Despite being from an earlier era, Watch on the Rhine is as relatable today as when it was written and equally potent. This piece ferociously addresses the rise of fascism and the importance of standing in your own truth, even if it makes you an outsider. Truly a force to be reckoned with, Hellman did not waiver in her political stance and continued to be a leader of the feminist movement despite popular opinion. I appreciate that boldness and tenacity. -

Critical Study on History of International Cinema

Critical Study on History of International Cinema *Dr. B. P. Mahesh Chandra Guru Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri Karnataka India ** Dr.M.S.Sapna ***M.Prabhudevand **** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar India ABSTRACT The history of film began in the 1820s when the British Royal Society of Surgeons made pioneering efforts. In 1878 Edward Muybridge, an American photographer, did make a series of photographs of a running horse by using a series of cameras with glass plate film and fast exposure. By 1893, Thomas A. Edison‟s assistant, W.K.L.Dickson, developed a camera that made short 35mm films.In 1894, the Limiere brothers developed a device that not only took motion pictures but projected them as well in France. The first use of animation in movies was in 1899, with the production of the short film. The use of different camera speeds also appeared around 1900 in the films of Robert W. Paul and Hepworth.The technique of single frame animation was further developed in 1907 by Edwin S. Porter in the Teddy Bears. D.W. Griffith had the highest standing among American directors in the industry because of creative ventures. The years of the First World War were a complex transitional period for the film industry. By the 1920s, the United States had emerged as a prominent film making country. By the middle of the 19th century a variety of peephole toys and coin machines such as Zoetrope and Mutoscope appeared in arcade parlors throughout United States and Europe. By 1930, the film industry considerably improved its technical resources for reproducing sound. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Sociology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds Recommended Citation Halbgewachs, Nancy Copeland. "Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Candidate Department of Sociology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. George A. Huaco , Chairperson Dr. Richard Couglin Dr. Susan Tiano Dr. James D. Stone i CENSORSHIP AND HOLOCAUST FILM IN THE HOLLYWOOD STUDIO SYSTEM BY NANCY COPELAND HALBGEWACHS B.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1962 M.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1966 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2011 ii DEDICATION In memory of My uncle, Leonard Preston Fox who served with General Dwight D. Eisenhower during World War II and his wife, my Aunt Bonnie, who visited us while he was overseas. My friend, Dorothy L. Miller who as a Red Cross worker was responsible for one of the camps that served those released from one of the death camps at the end of the war. -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, 1875-1972

Guide to the Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, 1875-1972 Brooklyn Public Library Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY 11238 Contact: Brooklyn Collection Phone: 718.230.2762 Fax: 718.857.2245 Email: [email protected] www.brooklynpubliclibrary.org Processed by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier. Finding aid created in 2006. Revised and expanded in 2008. Copyright © 2006-2008 Brooklyn Public Library. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Creator: Various Title: Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection Date Span: 1875-1972 Abstract: The Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection consists of 800 playbills and programs for motion pictures, musical concerts, high school commencement exercises, lectures, photoplays, vaudeville, and burlesque, as well as the more traditional offerings such as plays and operas, all from Brooklyn theaters. Quantity: 2.25 linear feet Location: Brooklyn Collection Map Room, cabinet 11 Repository: Brooklyn Public Library – Brooklyn Collection Reference Code: BC0071 Scope and Content Note The 800 items in the Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, which occupies 2.25 cubic feet, easily refute the stereotypes of Brooklyn as provincial and insular. From the late 1880s until the 1940s, the period covered by the bulk of these materials, the performing arts thrived in Brooklyn and were available to residents right at their doorsteps. At one point, there were over 200 theaters in Brooklyn. Frequented by the rich, the middle class and the working poor, they enjoyed mass popularity. With materials from 115 different theaters, the collection spans almost a century, from 1875 to 1972. The highest concentration is in the years 1890 to 1909, with approximately 450 items. -

Carleton Maize.Pdf

1993 Dizzy Gillespie/Sun Ra Memorial Invitational November 12-13, 1993 CARLETON COLLEGE - MAIZE TOSS-UPS Home of the annual National Rotten Sneaker competition, this city was also the birthplace of Admiral George Dewey. Located on the Winooski River, its major industries include granite, insurance, and tourism. FTP, name this capital of the 14th state admitted to the union. ANSWER: Montpelier, VT Chris Evert, Henry of Navarre, Longfellow, Peter Pan, Oedipus, John Henry, and Sir Barton. These are, FTP, members of what sport's national Hall of Fame, located in Saratoga Springs, New York, whose members also include Alydar, Seabiscuit, and Whirlaway? ANSWER: Horse Racing (accept "Race Horses" or equivalent answer on an early buzz) A museum dedicated to him opened on June 17, 1993 in a classical-style renovated Christian Science church in Huntington, Indiana. FTP, name this former National Guardsman turned politician. ANSWER: J. Danforth Quayle Famed for works of dreamlike incongruity, such as Rape, in which he substitutes a torso for a face, his other major paintings include The Wind and the Song and The Human Condition. For 10 points, identify this 20th century Belgian surrealist. ANSWER: Rene Magritte For a quick ten points, the name's more or less the same: the second-largest city in EI Salvador, the winds that contributed to the devastating fires near Los Angeles in October 1993, and the former president of Mexico who commanded the victorious army at the Alamo in 1836. ANSWER: Santa Ana (or Santa Anna) The most famous was that issued by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1713, which was confirmed in 1748 by the treaty of Aix-Ia-Chapelle.