Turn of the Century Women's Poetry the Context It Needs to Be Appreciated, Understood, and Valued

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry of Alice Meynell and Its Literary Contexts, 1875-1923 Jared Hromadka Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The al ws of verse : the poetry of Alice Meynell and its literary contexts, 1875-1923 Jared Hromadka Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hromadka, Jared, "The al ws of verse : the poetry of Alice Meynell and its literary contexts, 1875-1923" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1246. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1246 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE LAWS OF VERSE: THE POETRY OF ALICE MEYNELL AND ITS LITERARY CONTEXTS, 1875-1923 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Jared Hromadka B.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 M.A., Auburn University, 2006 August 2013 for S. M. and T. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks is due to Dr. Elsie Michie, without whose encouragement and guidance this project would have been impossible. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..............................................................................................................iii -

John Buchan's Uncollected Journalism a Critical and Bibliographic Investigation

JOHN BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM A CRITICAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM Volume One INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. 1 A: LITERATURE AND BOOKS…………………………………………………………………….. 11 B: POETRY AND VERSE…………………………………………………………………………….. 30 C: BIOGRAPHY, MEMOIRS, AND LETTERS………………………………………………… 62 D: HISTORY………………………………………………………………………………………………. 99 E: RELIGION……………………………………………………………………………………………. 126 F: PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE………………………………………………………………… 130 G: POLITICS AND SOCIETY……………………………………………………………………… 146 Volume Two H: IMPERIAL AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS……………………………………………………… 178 I: WAR, MILITARY, AND NAVAL AFFAIRS……………………………………………….. 229 J: ECONOMICS, BUSINESS, AND TRADE UNIONS…………………………………… 262 K: EDUCATION……………………………………………………………………………………….. 272 L: THE LAW AND LEGAL CASES………………………………………………………………. 278 M: TRAVEL AND EXPLORATION……………………………………………………………… 283 N: FISHING, HUNTING, MOUNTAINEERING, AND OTHER SPORTS………….. 304 PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM INTRODUCTION This catalogue has been prepared to assist Buchan specialists and other scholars of all levels and interests who are seeking to research his uncollected journalism. It is based on the standard reference work for Buchan scholars, Robert G Blanchard’s The First Editions of John Buchan: A Collector’s Bibliography (1981), which is generally referred to as Blanchard. The catalogue builds on this work -

An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1949 An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature Gertrude Agnes Carter Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Gertrude Agnes, "An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature" (1949). Master's Theses. 744. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1949 Gertrude Agnes Carter AN ANALYSIS OF THE POETRY OF ALICE MEYNELL ON THE BASIS OF HER PERSOIlAL PRIBCIl'LES OF LlTERAl'URE BY' Sister Gertrude Agnes Carter A THESIS SUBMITTED IN .t'AH.1'!AL FtJLFlLUlENT OF THE REQUIRl!:MENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF AR'rS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY June 1949 VITA Sister Gertrude Agnes was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, August 31, 1898. She attended St. Rose Ch'ammar and High Schools in Chelsea. The Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in English was con£erred on her by St. Mary-of-the-Woods College, Indiana, June, 1932. In 1942 she received .t'rom the Indiana State Board of Education a lire license to teach Social Studies in the accredited high schools of Indiana The writer has taught in St. -

Guide to the Alice Meynell Collection 1870S

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Alice Meynell Collection 1870s © 2016 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 4 Subject Headings 4 INVENTORY 4 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.MEYNELLA Title Meynell, Alice. Collection Date 1870s Size 0.25 linear feet (1 box) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Alice Christiana Gertrude Meynell (1847-1922) English writer, editor, critic, suffragist and poet. The collection contains ten letters sent by Meynell to a Mrs. Burchett. The letters are believed to have been written before 1877. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Meynell, Alice. Correspondence, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Biographical Note Alice Christiana Gertrude Meynell was born in October 11, 1847, in Barnes, London, to Thomas James and Christiana Thompson. As a child, she and her family moved around England, Switzerland, and France, though Meynell spent most of her youth in Italy. Meynell published her first collection of poetry, Preludes, in 1875. Though it received little public attention, the famed English art critic John Ruskin praised her work. Meynell converted to the Catholic Church at some point prior to 1868 and her family followed suit. Her conversion focused her writing in religious matters. This new focus led her to meet a Catholic newspaper editor, Wilfrid Meynell (1852-1948) in 1876. -

Boston College Collection of Francis Thompson 1876-1966 (Bulk 1896-1962) MS.2006.023

Boston College Collection of Francis Thompson 1876-1966 (bulk 1896-1962) MS.2006.023 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2815 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 9 I: Created or collected by Thompson ......................................................................................................... 9 -

Alice Meynell As Mother, Mentor, and Muse

1 “Authorship Prevails in Nurseries”: Alice Meynell as Mother, Mentor, and Muse Kirsty Bunting Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UKABSTRACT Viola Meynell was raised in an at-home magazine office and trained in aestheticist poetry of the 1890s by her mother, Alice Meynell. Making use of extensive and previously unpublished correspondence between Alice and Viola from the Meynell family archive, this essay charts Viola’s rebellious turn towards the novel form and early experimental modernism, and her rebellion’s impact on the mother-daughter relationship. The two women wrote about each other in myriad poetry, essays, fiction, and biography, and, when read side by side, these writings offer an intriguing picture of their lives together and trace alternating periods of generational distance and intimacy. Specifically, the article traces Alice’s reification in print as ideal wife, mother, and homemaker, and contrasts this ideal with Viola’s daily observations of her mother. Before and after Alice’s death, Viola fought to demythologize, reclaim, celebrate, and mourn the real Alice Meynell in her work, while her own literary reputation was damaged by her association with the domestic and her prolonged apprenticeship under her mother. Alice Meynell (1847-1922) had her literary apprenticeship under the instruction of the high- Victorian literary giants of her parents’ bohemian circle, including Coventry Patmore, Ruskin, and Tennyson. She became one of the most celebrated female poets and essayists of the 1890s, contending for the role of Poet Laureate.1 Brought up to the profession of poet, Alice similarly apprenticed her own children, and she tutored none more intensively than her daughter Viola (1885-1956), the only of Alice’s eight children who would go on to make a living by writing. -

An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature Gertrude Agnes Carter Loyola University Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1949 An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature Gertrude Agnes Carter Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Carter, Gertrude Agnes, "An Analysis of the Poetry of Alice Meynell on the Basis of Her Personal Principles of Literature" (1949). Master's Theses. Paper 744. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1949 Gertrude Agnes Carter AN ANALYSIS OF THE POETRY OF ALICE MEYNELL ON THE BASIS OF HER PERSOIlAL PRIBCIl'LES OF LlTERAl'URE BY' Sister Gertrude Agnes Carter A THESIS SUBMITTED IN .t'AH.1'!AL FtJLFlLUlENT OF THE REQUIRl!:MENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF AR'rS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY June 1949 VITA Sister Gertrude Agnes was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, August 31, 1898. She attended St. Rose Ch'ammar and High Schools in Chelsea. The Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in English was con£erred on her by St. Mary-of-the-Woods College, Indiana, June, 1932. In 1942 she received .t'rom the Indiana State Board of Education a lire license to teach Social Studies in the accredited high schools of Indiana The writer has taught in St. -

Proquest Dissertations

643 UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES ALICE MEYNELL — CRITIC by Sister Saint Helena of the Cross, C.N.D. (Mary Helena Cawley) This thesis is presented to the English Department of the Graduate School of the Faculty of Arts, University of Ottawa. It is presented aa part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. v^Sit'd'?fe BJB-L.'OTHE^JES Ifj^M rjt. v Ottawa Ottawa. Canada 1957 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA .. SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53766 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform DC53766 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES Appreciation and gratitude are herein expressed to Dr. Emmett 0'Grady, Head of the Department of English of the University of Ottawa. This thesis was prepared under the direction and guidance of Dr. 0'Grady. UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES CURRICULUM STUDIORUM Sister St. -

The Selected Letters of Katharine Tynan

The Selected Letters of Katharine Tynan The Selected Letters of Katharine Tynan: Poet and Novelist Edited by Damian Atkinson The Selected Letters of Katharine Tynan: Poet and Novelist Edited by Damian Atkinson This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Damian Atkinson All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8695-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8695-6 In memory of Deborah Hayward Eaton sometime Librarian St Edmund Hall, Oxford Katharine Tynan aged thirty (Magazine of Poetry, 1889) CONTENTS Note .......................................................................................................... viii List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... x Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Editorial Procedures .................................................................................. 18 Sources of Letters and Short Titles ........................................................... -

Verse Cultures of the Long Nineteenth Century

introduction A Great Multiplication of Meters jason david hall The long nineteenth century (the period to which the present book is de- voted) was simply awash with meter, and it mattered in more ways, and to more people, than most of us, from our twenty-first-century vantage point, readily appreciate. So abundant, in fact, was the metrical output of the period that the eminent turn-of-the-century prosodist George Saintsbury devoted a whole book to it: the third and final volume of his epic A History of English Prosody from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day (1906–10) con- centrates exclusively on meters “From Blake to Mr. Swinburne.” His com- pendious study catalogues an array of feet and forms—from the usual to the more exceptional suspects. Alongside the proliferation of ballad meters, perfect as well as “minced or colloped decasyllabic lines,” and much-debated hexameters (which receive a chapter of their own), one finds several less frequently remembered (and even less discussed) measures: Swinburne’s “‘Dolores’ metre,” the “fourteener metre” of William Morris’s Sigurd the Volsung (1876), the “Whitmanically” arranged meters of William Ernest Henley’s A Song of Speed (1903), and “other out-of-the-way measures”1— alcaic meters, choriambic meters, galliambic meters, sapphic meters, and various imported French measures and stanzas. Even a “deeply traditional poet” such as William Wordsworth, as Brennan O’Donnell reminds us, not only attempted to renovate blank verse but also used “nearly ninety different 1 2 jason david hall stanza forms.”2 Indeed, so staggering was the “multitude of metres”3 in circulation that nineteenth-century poets and readers sometimes struggled to make sense of—not to mention agree on—matters of versification. -

Boston College Collection of Alice Meynell 1875-1938, Undated MS.1986.061

Boston College Collection of Alice Meynell 1875-1938, undated MS.1986.061 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1140 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 7 I: Correspondence ....................................................................................................................................... -

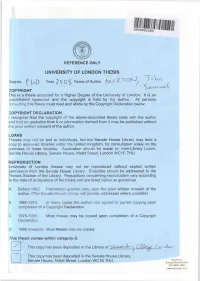

UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS Degree

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS T.U, Degree ^ | / \ f ) Year20 0$ Name of Author (KVV\ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, It is an jnpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting this thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962-1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975-1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D.