HOPE IS the LAST to DAI This Page Intentionally Left Blank HOPE IS the LAST to DAI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUI Working Papers

MAX WEBER PROGRAMME EUI Working Papers MWP 2009/09 MAX WEBER PROGRAMME AFTER LIBERATION: THE JOURNEY HOME OF JE WISH SURVIVORS IN POLAND AND SLOVAKIA, 1944-46 Anna Cichopek EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE , FLORENCE MAX WEBER PROGRAMME After Liberation: the Journey Home of Jewish Survivors in Poland and Slovakia, 1944-46 ANNA CICHOPEK EUI W orking Paper MWP 2009/09 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Max Weber Programme of the EUI if the paper is to be published elsewhere, and should also assume responsibility for any consequent obligation(s). ISSN 1830-7728 © 2009 Anna Cichopek Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract In this paper, I tell the stories of Jewish survivors who made their way to their hometowns in Poland and Slovakia between the fall of 1944 and summer 1948. I describe liberation by the Soviet Army and attitudes toward the liberators in Poland and Slovakia. I ask what the Jewish position was in the complex matrix of Polish-Russian relations in 1944 and 1945. Then I follow the survivors during the first hours, days, and weeks after liberation. -

PDF EPUB} Hope Is the Last to Die a Coming of Age Under Nazi Terror by Halina Birenbaum Search All 1 Records in Our Collections

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hope Is the Last to Die A Coming of Age Under Nazi Terror by Halina Birenbaum Search All 1 Records in Our Collections. The Museum’s Collections document the fate of Holocaust victims, survivors, rescuers, liberators, and others through artifacts, documents, photos, films, books, personal stories , and more. Search below to view digital records and find material that you can access at our library and at the Shapell Center. Hope is the last to die : a coming of age under Nazi terror / Halina Birenbaum ; translated from the Polish by David Welsh. About This Publication. Keywords and Subjects. Availability. Availability. Digitized Available for Research. Librarian View Give Feedback. Learn About the Holocaust. These additional online resources from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum will help you learn more about the Holocaust and research your family history. Holocaust Encyclopedia. The Holocaust Encyclopedia provides an overview of the Holocaust using text, photographs, maps, artifacts, and personal histories. Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center. Research family history relating to the Holocaust and explore the Museum's collections about individual survivors and victims of the Holocaust and Nazi persecution. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Learn about over 1,000 camps and ghettos in Volume I and II of this encyclopedia, which are available as a free PDF download. This reference provides text, photographs, charts, maps, and extensive indexes. HOPE IS THE LAST TO DIE: A COMING OF AGE UNDER NAZI TERROR (Nadzieja umiera ostatnia) Hope Is the Last To Die, published in English translation in 1996, is the autobiographical account of Polish-Jewish writer Halina Birenbaum's adolescent journey through the horrors of the Holocaust. -

Jews, Poles, and Slovaks: a Story of Encounters, 1944-48

JEWS, POLES, AND SLOVAKS: A STORY OF ENCOUNTERS, 1944-48 by Anna Cichopek-Gajraj A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Sz űcs, Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Piotr J. Wróbel, University of Toronto This dissertation is dedicated to my parents and Ari ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am greatly appreciative of the help and encouragement I have received during the last seven years at the University of Michigan. I have been fortunate to learn from the best scholars in the field. Particular gratitude goes to my supervisors Todd M. Endelman and Brian A. Porter-Sz űcs without whom this dissertation could not have been written. I am also thankful to my advisor Zvi Y. Gitelman who encouraged me to apply to the University of Michigan graduate program in the first place and who supported me in my scholarly endeavors ever since. I am also grateful to Piotr J. Wróbel from the University of Toronto for his invaluable revisions and suggestions. Special thanks go to the Department of History, the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies, and the Center of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Michigan. Without their financial support, I would not have been able to complete the program. I also want to thank the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture in New York, the Ronald and Eileen Weiser Foundation in Ann Arbor, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, and the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC for their grants. -

Tell Ye Your Children

Tell Ye Your Children… Your Ye Tell Tell Ye Your Children… STÉPHANE BRUCHFELD AND PAUL A. LEVINE A book about the Holocaust in Europe 1933-1945 – with new material about Sweden and the Holocaust THE LIVING HISTORY FORUM In 1997, the former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson initiated a comprehensive information campaign about the Holocaust entitled “Living History”. The aim was to provide facts and information and to encourage a discussion about compassion, democracy and the equal worth of all people. The book “Tell Ye Your Children…” came about as a part of this project. The book was initially intended primarily for an adult audience. In 1999, the Swedish Government appointed a committee to investigate the possibilities of turning “Living History” into a perma- nent project. In 2001, the parliament decided to set up a new natio- nal authority, the Living History Forum, which was formally establis- hed in 2003. The Living History Forum is commissioned to work with issues related to tolerance, democracy and human rights, using the Holocaust and other crimes against humanity as its starting point. This major challenge is our specific mission. The past and the pre- sent are continuously present in everything we do. Through our continuous contacts with teachers and other experts within education, we develop methods and tools for reaching our key target group: young people. Tell Ye Your Children… A book about the Holocaust in Europe 1933–1945 – THIRD REVISED AND EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION – STÉPHANE BRUCHFELD AND PAUL A. LEVINE Tell Ye Your -

"So Spielen Wir Auf Dem Friedhof" | Ilse Aichinger's "Die Grossere Hoffnung" and "The Holocaust Through the Eyes of a Child"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2002 "So spielen wir auf dem Friedhof" | Ilse Aichinger's "Die grossere Hoffnung" and "The Holocaust through the eyes of a child" Emily P. Sepp The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sepp, Emily P., ""So spielen wir auf dem Friedhof" | Ilse Aichinger's "Die grossere Hoffnung" and "The Holocaust through the eyes of a child"" (2002). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1447. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1447 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M aureen and iMüke Mmspmm i#BAm The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: Date: HflU^ 2^0 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 „...so spielen wir auf dem Friedhof': Use Aichinger's Die grossere Hoffnung the Holocaust through the Eyes of a Child by Emily P. -

Bein Polanit Le'ivrit. on the Polish-Hebrew Literary Bilingualism In

WIELOGŁOS Pismo Wydziału Polonistyki UJ 2018; Special Issue (English version), pp. 71–92 doi: 10.4467/2084395XWI.18.013.9881 www.ejournals.eu/Wieloglos Beata Tarnowska University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn Bein polanit le’ivrit. On the Polish-Hebrew Literary Bilingualism in Israel (Reconnaissance)* Keywords: bilingualism, Polish-Hebrew bilingual writers, Polish literature in Israel. The phenomenon of the Polish literary milieu in Israel was created by immi- grants who came to Eretz Israel between the interwar period and the March Aliyah, as well as later [see: Famulska-Ciesielska, Żurek]. Both writers leav- ing Poland with some achievements, as well as those who only started their literary work after many years in Israel, repeatedly faced the dilemma of what language to write in: Polish, which was the first language of assimilated Jews or those who strongly identified themselves as Jews, but who did not know any of the Jewish languages, or in Hebrew, which was often only learnt in the New Country?1 At the time the Israeli statehood was being formed, Hebrew was the third official language of Palestine alongside Arabic and English, and since 1948 the official language of the State of Israel [Medinat Israel, see: Krauze, Zieliński, * Polish original: (2016) „Bejn polanit le’iwrit”. O polsko-hebrajskim bilingwizmie literackim w Izraelu. (Rekonesans). Wielogłos 2(28), pp. 99–123. 1 Bilingualism, which has always occupied a special place in the history of the Jewish nation, contributed to the creation of multilingual literature, created not only in Yiddish, Hebrew or Ladino, but also in the languages of the countries of settlement. -

Women in KL-Auschwitz, 1942-1945 Donna Didomenico

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1992 Women in KL-Auschwitz, 1942-1945 Donna DiDomenico Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation DiDomenico, Donna, "Women in KL-Auschwitz, 1942-1945" (1992). Honors Theses. Paper 311. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "i~llilfill11r11111~11ri~rntmir 3 3082 00688 8357 'Women in !I(L-Yluscliwitz 1942-1945 .- \':-,, . by Donna DiDomenico Honors Thesis in the Department of History University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia April 2, 1992 Advisor: Dr. Martin Ryle Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................ii Setting the Stage: A History of KL-Auschwitz ............................................................................................ 1 Women as Forced Laborers: Extermination Through Work....................................................................................... 5 Women as Prisoner Functionaries: Power and Privilege ....................................................................................................... 16 Women as Victims: Nazi Medicine and Experimentation ...........................................................................22 -

Testimonies and Poetry Written by Survivors

Yom HaShoah Ceremony Readings At some unconscious level, the image of the Holocaust is “with us” a memory which haunts, a sounding board for all subsequent evil in the back of the mind, not only for the normal, well-intentioned people … but for all of us now living: we, the inheritors. The triumph of the SS required that the tortured victim allow himself to be led to the gallows without protesting … There is nothing more terrible than these processions of human beings walking straight forward towards the unknown, living in hope based on their faith in man. Jean François-Steiner To seek A Human / Hanna Senesh In the flames of war, of fire, of the burned In the stormy oceans of blood I shall light my little lamp To seek, to seek a human The flames of the fire weaken my lamp Lights of fire are blinding my eyes How shall I see How will I look How will I know How will I recognize When he shall stand in front of me? Give me a sign God, Put a sign on his face Due to the fire, the burning and blood So that I shall recognize the pure brightness, the eternal I have been seeking for: A human. ______________________________________________________________ IsraelForever.org © 2013 The Israel Forever Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Elegy for the Little Jewish Towns Gone now are, gone are in Poland those little Jewish towns Hrubieszow, Karczew, Brody, Falenica You look for candlelight in the windows And for song in the wooden synagogue in vain Vanished the last leftovers, Jewish tatters Blood was buried by sand, traces were cleared And walls were lucidly -

Human Reciprocity Among the Jewish Prisoners in the Nazi Concentration Camps Shamai Davidson

Human Reciprocity Among the Jewish Prisoners in the Nazi Concentration Camps Shamai Davidson We are all brothers, and we are all suffering from the same fate. The same smoke floats over all our heads. Help one another. It is the only way to survive. (Elie Wiesel, Night, p. 55) It has become increasingly evident that cooperation for survival among members of the same species is a basic law of life. Throughout the history of man, sharing relationships have been a central mode of coping with and adapting to the environment. When the conditions of life are particularly harsh, making survival difficult, there is often an increase in reciprocal relationships. This has been demonstrated for example in the socio-cultural patterns of villages in the Arctic1. The Nazi concentration camp represents the most extreme situation for survival known to man. It was a central component in a system designed for killing many millions of human beings, primarily the Jews of Europe. These tormented people were all condemned to death, but the process took time and was not uniform, as it involved the killing of a scattered people in twenty-two different European states and regions. Even in the death camps, there was a technical limit to the numbers that could be killed every day. Meanwhile, as the processing for death went on inexorably, there was a delay in the death of those selected to work at various jobs in the death camp. Others were selected for a variety of slave labor under conditions that resulted in the death of many from injuries inflicted, exhaustion, exposure, disease and starvation. -

"Book of Names" - Project to Create a Database of People Murdered in Treblinka and Their Commemoration

"Book of Names" - project to create a database of people murdered in Treblinka and their commemoration Paweł Sawicki, Ewa Teleżyńska-Sawicka Foundation "Memory of Treblinka" - "Book of Names" - project to create a database of people murdered in Treblinka and their commemoration 0. Abstract Of the nearly one million Jews murdered in Treblinka, the vast majority are unknown by name and surname. The "Memory of Treblinka" Foundation collects a list of Treblinka victims. Close to 60,000 people have been collected to date. Nearly 42,500 have been published on memoryoftreblinka.org. Were found about 5,000 people, whose data are not in the Central Database of Yad Vashem Holocaust Victims, or in other large databases of Holocaust victims. The text discusses the sources that were used. The rules for placing data in the database are also presented. When creating a database, the authors had to face many problems and dilemmas. Apart from discussing them, the main challenges facing the base expansion and plans for further actions are presented. At the end of the article, there is a list of more important sources from which the information was obtained. 1. Introduction Everyone has a name. About 80 years ago, during World War II, millions of people were taken, disappeared. Not only were their lives taken, not only everything they had, but even their names and memory were taken. It happened, among many other places, here in Treblinka. German criminals wanted to annihilate the entire culture, history and heritage of Jews, the entire Jewish world. Whole communities were murdered - all its members without exceptions. -

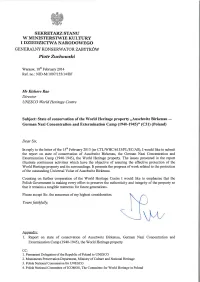

Piotr Zuchowski

SEKRETARZ STANU W MINISTERS1WIE KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO GENERALNY KONSERWATOR ZABITKOW Piotr Zuchowski Warsaw, lOth February 2014 Ref. no.: NID-M/1097/155/14/BF Mr Kishore Rao Director UNESCO World Heritage Centre Subject: State of conservation of the World Heritage property ,Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945)" (C31) (Poland) Dear Sir, In reply to the letter of the 15th February 2013 (nr CTL/WHC/6133/PL/EC/AS), I would like to submit the report on state of conservation of Auschwitz Birkenau, the German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945), the World Heritage property. The issues presented in the report illustrate continuous activities which have the objective of assuring the effective protection of the World Heritage property and its surroundings. It presents the progress of work related to the protection of the outstanding Universal Value of Auschwitz Birkenau. Counting on further cooperation of the World Heritage Centre I would like to emphasise that the Polish Government is making every effort to preserve the authenticity and integrity of the property so that it remains a tangible memento for future generations. Please accept Sir, the assurance of my highest consideration. Yours faithfully, Appendix: 1. Report on state of conservation of Auschwitz Birkenau, German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945), the World Heritage property CC: 1. Permanent Delegation of the Republic of Poland to UNESCO 2. Monuments Preservation Department, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage 3. Polish National Commission for UNESCO 4. Polish National Committee ofiCOMOS, The Committee for World Heritage in Poland Warsaw, 31 January 2014 Report on the UNESCO World Heritage Site Auschwitz Birkenau, German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945) (Poland) (C-31) This Report presents the current state of conservation of the Outstanding Universal Value of Auschwitz Birkenau, German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945) and its surroundings. -

The Holocaust Remembered on the 75Th Anniversary of the Liberation of Europe | the Star

5/8/2020 The Holocaust remembered on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Europe | The Star This copy is for your personal non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies of Toronto Star content for distribution to colleagues, clients or customers, or inquire about permissions/licensing, please go to: www.TorontoStarReprints.com CANADA The Holocaust remembered on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Europe Thu., May 7, 2020 5 min. read May 8 marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Europe — and many thousands of Holocaust survivors — from the brutal terror of Nazi Germany. Today there are approximately 350,000 Holocaust survivors still alive around the world. Many of these survivors overcame their trauma, and began their lives again — starting new families, launching careers and founding businesses, becoming active contributors to their communities and their societies as a whole. Many continue to share their stories with young people. Yet, as any survivor will readily acknowledge, they live constantly with their tragic memories. In the twilight of their lives, many survivors have taken to recording their life stories, so that the memory of their family members is preserved, and so that the record of their extraordinary experiences — and the lessons to be learned from them — is not lost to future generations. Here are excerpts and photos of some of their stories taken from Witness: Passing the Torch of Holocaust Memory to New Generations, compiled by Eli Rubenstein: Prisoner 157615 https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/05/07/the-holocaust-remembered-on-the-75th-anniversary-of-the-liberation-of-europe.html 1/8 5/8/2020 The Holocaust remembered on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Europe | The Star “My father, Icek (Irving) Cymbler from Zawiercie, Poland, was prisoner number 157615.