'Celtic' Clothing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kilts & Tartan

Kilts & Tartan Made Easy An expert insider’s frank views and simple tips Dr Nicholas J. Fiddes Founder, Scotweb Governor, Why YOU should wear a kilt, & what kind of kilt to get How to source true quality & avoid the swindlers Find your own tartans & get the best materials Know the outfit for any event & understand accessories This e-book is my gift to you. Please copy & send it to friends! But it was a lot of work, so no plagiarism please. Note my copyright terms below. Version 2.1 – 7 November 2006 This document is copyright Dr Nicholas J. Fiddes (c) 2006. It may be freely copied and circulated only in its entirety and in its original digital format. Individual copies may be printed for personal use only. Internet links should reference the original hosting address, and not host it locally - see back page. It may not otherwise be shared, quoted or reproduced without written permission of the author. Use of any part in any other format without written permission will constitute acceptance of a legal contract for paid licensing of the entire document, at a charge of £20 UK per copy in resultant circulation, including all consequent third party copies. This will be governed by the laws of Scotland. Kilts & Tartan - Made Easy www.clan.com/kiltsandtartan (c) See copyright notice at front Page 1 Why Wear a Kilt? 4 Celebrating Celtic Heritage.................................................................................................. 4 Dressing for Special Occasions.......................................................................................... -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for January 23Rd, 2015

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for January 23rd, 2015 To see what we've added to the Electric Scotland site view our What's New page at: http://www.electricscotland.com/whatsnew.htm To see what we've added to the Electric Canadian site view our What's New page at: http://www.electriccanadian.com/whatsnew.htm For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: http://www.electricscotland.com/ Electric Scotland News I've actually been reading rather than publishing this week. I got hooked on reading the biography of Lord Strathconna and Mount Royal which was a very enjoyable read. I'd previously put up a biography about him but that one almost ignored his early life in both Scotland and Canada. I was also taken with all the work he did for Newfoundland to promote the area economically. He also created an experimental farm which demonstrated that you could live well as long as you were well organised and so as one person put it when visiting him he enjoyed all the best in beef, pork and lamb along with fresh vegetables. I've made this book available and you'll see a link to it below. ----- And as this coming Saturday usually sees the Burns Suppers being celebrated all over the world I've made available a great book by the Rev. Paul who is credited with starting the Burns Suppers. The book is... The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns with a Life of the Author Containing a Variety of Particulars, drawn from sources inaccessible by former Biographers to which is subjoined an Appendix of a Panegyrical Ode, and a demonstration of Burns' Superiority to every other poet as a writer of Songs, by Rev. -

The Dürrnberg Salt Metropolis: Catalyst of Communication and 393 Complexity in La Tène Central Europe Holger Wendling

CROSSING THE ALPS EARLY URBANISM BETWEEN NORTHERN ITALY AND CENTRAL EUROPE (900-400 BC) This is a free offprint – as with all our publications the entire book is freely accessible on our website, and is available in print or as PDF e-book. www.sidestone.com CROSSING THE ALPS EARLY URBANISM BETWEEN NORTHERN ITALY AND CENTRAL EUROPE (900-400 BC) Edited by Lorenzo Zamboni, Manuel Fernández-Götz & Carola Metzner-Nebelsick This is a free offprint – as with all our publications the entire book is freely accessible on our website, and is available in print or as PDF e-book. www.sidestone.com © 2020 Individual authors Published by Sidestone Press, Leiden www.sidestone.com Lay-out & cover design: Sidestone Press Cover image: LandesamtfürDenkmalpflegeimRegierungsprӓsidiumStuttgart;FaberCourtial Section images: Karsten Wentink Backcoverimage:MuseoDeltaAnticoComacchio;InkLink ISBN 978-90-8890-961-0 (softcover) ISBN 978-90-8890-962-7 (hardcover) ISBN978-90-8890-963-4(PDFe-book) Contents PART 1: URBAN ORIGINS AND TRAJECTORIES ACROSS THE ALPS 1. Early Urbanism South and North of the Alps: An Introduction 11 Lorenzo Zamboni, Manuel Fernández-Götz & Carola Metzner-Nebelsick 2. Aspects of Urbanism in Later Bronze Age Northern Italy 19 Mark Pearce 3. Urbanisation and Deurbanisation in the European Iron Age: 27 Definitions, Debates, and Cycles Manuel Fernández-Götz 4. From Genoa to Günzburg. New Trajectories of Urbanisation 43 and Acculturation between the Mediterranean and South-Central Europe Louis Nebelsick & Carola Metzner-Nebelsick PART 2: EARLY URBANISATION PROCESSES IN NORTHERN ITALY 5. Verucchio: The Iron Age Settlement 71 Paolo Rondini & Lorenzo Zamboni 6. Archaeology of Early Felsina. The Birth of a Villanovan City 91 Jacopo Ortalli 7. -

Differential Grain Use on the Titelberg, Luxembourg

]. Ethnobiol. 2(1): 79-88 May 1982 DIFFERENTIAL GRAIN USE ON THE TITELBERG, LUXEMBOURG RALPH M. ROWLETT and ANNE L. PRICE Department ofAnthropology, University ofMissouri-Columbia Columbia, MO. 65211 MARIA HOPF Emeritus Curator of Ethnobotany, Romisch-Germanische Zentral Museum Mainz Federal Republic of Germany ABSTRACT.-The "Titelberg," Luxembourg, is an Iron Age hillfort which was occupied from La Tene II (ca. 200 B.C.) until the end of the Roman Empire in northern Gaul (ca. A.D. 400). Prior to the Iron Age there was also a Neolithic use of the mountain top in the third millenium B.C. From the Iron Age until its abandonment, the Titelberg was mainly populated by Celtic folk, apparently of the Treveri tribal chiefdom. Carbonized cereal grains have been recovered from most levels. At the emplacement excavated by the Uni versity of Missouri, there were a stratified series of mint foundries. From the late Neolithic comes a small variety of wheat, while oats appear as early as the hearths of La Tene II. From the Dalles Floor phase, after the Roman conquest, barley is the most frequently encountered grain. Bread wheat does not make a strong appearance until the late fourth century, when either the last inhabitants of the Titelberg or immigrating Franks left the most recent feature to be excavated. Although the remains are found in the context of a continuing cultural tradition, the particular combinations of cereals recovered change with either major shifts in cultural trajectory or the appearance of intrusive cultures nearby. These changes seem not necessarily "caused" simply by either overt introductions or the prestige of the intrusive culture, but as a way to adjust to other factors, such as taxation, political status, and meat supply. -

Library Author List 12:2020

SDCWG LIBRARY INVENTORY December 2020 SORTED BY AUTHOR Shelf Author Title Subject Location Abel, Isabel Multiple Harness Patterns Weaving Instruction Adelson, Laurie Weaving Tradition of Highland Bolivia Ethnic Textiles Adrosko, Rita Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing Dyeing Adrosko, Rita Natural Dyes in the United States Dyeing Ahnlund, Gunnila Vava Bilder (Swedish Tapestry) Ethnic Textiles Albers, Anni On Designing Design Albers, Anni On Weaving General Weaving Albers, Josef Interaction of Color Design Alderman, Sharon D. Handwoven, Tailormade Clothing Alderman, Sharon D. Handweaver's Notebook General Weaving Alderman, Sharon D. Mastering Weave Structures Weaving Patterns Alexander, Marthann Weaving Handcraft General Weaving Allard, Mary Rug Making Techniques and Design Rug Weaving Allen, Helen Louise American & European Hand Weaving General Weaving American Craft Museum Diane Itter: A retrospective Catalog American Tapestry American Tapestry Biennial I Tapestry Alliance American Tapestry American Tapestry Today Tapestry Alliance American Tapestry Panorama of Tapestry, Catalog Tapestry Alliance American-Scandinavian The Scandinavian Touch Ethnic Textiles Foundation Amos, Alden 101 Questions for Spinners Spinning 1 SDCWG LIBRARY INVENTORY December 2020 SORTED BY AUTHOR Shelf Author Title Subject Location Amsden, Charles A. Navaho Weaving Navajo Weaving Anderson, Clarita Weave Structures Used In North Am. Coverlets Weave Structures Anderson, Marilyn Guatemalan Textiles Today Ethnic Textiles Anderson, Sarah The Spinner’s Book of Yarn Designs -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

Routes4u Project Feasibility Study on the Roman Heritage Route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region

Routes4U Project Feasibility Study on the Roman Heritage Route in the Adriatic and Ionian Region Routes4U Feasibility Study on an Iron Age cultural route in the Danube Region Routes4U Project Routes4U Feasibility study on an Iron Age cultural route in the Danube Region ROUTES4U FEASIBILITY STUDY ON AN IRON AGE CULTURAL ROUTE IN THE DANUBE REGION August 2019 The present study has been developed in the framework of Routes4U, the Joint Programme between the Council of Europe and the European Commission (DG REGIO). Routes4U aims to foster regional development through the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe programme in the four EU macro-regions: the Adriatic and Ionian, Alpine, Baltic Sea and Danube Regions. A special thank you goes to the author Martin Fera, and to the numerous partners and stakeholders who supported the study. The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. www.coe.int/routes4u 2 / 57 Routes4U Feasibility study on an Iron Age cultural route in the Danube Region CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 5 II. ANALYSIS OF THE “STATE OF THE ART” OF IRON AGE HERITAGE IN THE DANUBE REGION............................................................................................................................... -

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’S Cotton Frontier C.1890-1950

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’s Cotton Frontier c.1890-1950 By Jack Southern A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of a PhD, at the University of Central Lancashire April 2016 1 i University of Central Lancashire STUDENT DECLARATION FORM I declare that whilst being registered as a candidate of the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another aware of the University or other academic or professional institution. I declare that no material contained in this thesis has been used for any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work. Signature of Candidate ________________________________________________ Type of Award: Doctor of Philosophy School: Education and Social Sciences ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the evolution of identity and community within north east Lancashire during a period when the area gained regional and national prominence through its involvement in the cotton industry. It examines how the overarching shared culture of the area could evolve under altering economic conditions, and how expressions of identity fluctuated through the cotton industry’s peak and decline. In effect, it explores how local populations could shape and be shaped by the cotton industry. By focusing on a compact area with diverse settlements, this thesis contributes to the wider understanding of what it was to live in an area dominated by a single industry. The complex legacy that the cotton industry’s decline has had is explored through a range of settlement types, from large town to small village. -

[email protected]

[email protected] http://ttusher.orgfree.com Textile manufacturing terminology The manufacture of textiles is one of the oldest of human technologies. In order to make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fibre from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. (Both fibre and fiber are used in this article.) The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving, which turns yarn into cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. For decoration, the process of colouring yarn or the finished material is dyeing. For more information of the various steps, see textile manufacturing. A__________________________________________________________________ Absorbency A measure of how much water a fabric can absorb. Acetate Acetate is a synthetic fiber. Acrylic Acrylic fiber is a synthetic polymer fiber that contains at least 85% acrylonitrile. Aida cloth Aida cloth is a coarse open-weave fabric traditionally used for cross-stitch. Alnage Alnage is the official supervision of the shape and quality of manufactured woolen cloth. Alpaca Alpaca is a name given to two distinct things. It is primarily a term applied to the wool of the Peruvian alpaca. It is, however, more broadly applied to a style of fabric originally made from alpaca fiber but now frequently made from a similar type of fiber. Angora Angora refers to the hair of either the Angora goat or the Angora rabbit, or the fabric made from Angora rabbit; see Angora wool. (Fabric made from angora goat is mohair.) Angora wool Angora wool is a generic term for either Mohair if the hair is from an Angora goat or Angora fabric if the hair is from an Angora rabbit. -

Architecture, Style and Structure in the Early Iron Age in Central Europe

TOMASZ GRALAK ARCHITECTURE, STYLE AND STRUCTURE IN THE EARLY IRON AGE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Wrocław 2017 Reviewers: prof. dr hab. Danuta Minta-Tworzowska prof. dr hab. Andrzej P. Kowalski Technical preparation and computer layout: Natalia Sawicka Cover design: Tomasz Gralak, Nicole Lenkow Translated by Tomasz Borkowski Proofreading Agnes Kerrigan ISBN 978-83-61416-61-6 DOI 10.23734/22.17.001 Uniwersytet Wrocławski Instytut Archeologii © Copyright by Uniwersytet Wrocławski and author Wrocław 2017 Print run: 150 copies Printing and binding: "I-BIS" Usługi Komputerowe, Wydawnictwo S.C. Andrzej Bieroński, Przemysław Bieroński 50-984 Wrocław, ul. Sztabowa 32 Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER I. THE HALLSTATT PERIOD 1. Construction and metrology in the Hallstatt period in Silesia .......................... 13 2. The koine of geometric ornaments ......................................................................... 49 3. Apollo’s journey to the land of the Hyperboreans ............................................... 61 4. The culture of the Hallstatt period or the great loom and scales ....................... 66 CHAPTER II. THE LA TÈNE PERIOD 1. Paradigms of the La Tène style ................................................................................ 71 2. Antigone and the Tyrannicides – the essence of ideological change ................. 101 3. The widespread nature of La Tène style ................................................................ -

Electronic Report

Electronic Report 52 Bank Parade Burnley BB11 1TS Phone 01282 414649 / 458410 Our Ref: Talbot St/BB10 2HW/2017 Date: 19 July 2017 Steven Hartley Hartley Planning and Development Associates Swallow Barn Lower Chapel Hill Hurst Lane Rawtenstall BB4 8TB WALSHAW MILL, TALBOT STREET, BRIERCLIFFE, BURNLEY. BB10 2HW PRELIMINARY RISK ASSESSMENT (DESK STUDY) INTRODUCTION A residential development is proposed. The objective is to carry out a desk study, supplemented with a walk over survey, to form a Preliminary Risk Assessment to consider contamination, landfill gas and geotechnical issues. SITE DESCRIPTION The site is an almost rectangular plot, about 137 by 126 metres, located to the southwest of Talbot Street in Briercliffe and at OS Grid Reference 386492, 434915. A limited inspection on 4/7/17 by Mr S Gimeno (Geotechnician) showed the site to comprise a former cotton mill, now used for pharmaceutical manufacture, with yards to the east and south and a grass field to the west. The main building was a north light weaving shed and joined to the south was stone built with extensions and alterations. To the west was a portacabin style hard roof office probably built of timber. Just north was a fenced compound for aircon condenser units. In the southeast corner was a stone built electrical substation. In the northeast corner was a gas regulator box/building. An oil drum with hand pump was seen in the southeast corner. This is a residential area with houses on all sides, including gardens to the north, southeast and southwest. The area slopes down to the southwest at about 1 in 25. -

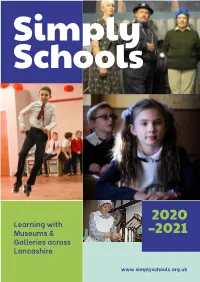

Simply Schools 2020–21

2020 Learning with Museums & –2021 Galleries across Lancashire www.simplyschools.org.uk Welcome to Welcome to the Simply Schools 2020–21 brochure, we are confident that you will find ideas and inspiration from our Heritage Learning site activities, CPD, loans boxes and outreach, and from those activities delivered by our wider museum partners. Heritage Learning is back for 2020/2021 It gives me the greatest pleasure to with new sessions, projects and announce that the Heritage Learning programmes. Last year the Heritage Team will be delivering the learning Learning Team delivered site sessions, programmes on behalf of the Harris outreach and loans boxes that engaged Museum, Art Gallery and Library in with over 35,000 school children Preston from September 2020. across Lancashire. We have once again David Brookhouse worked with schools on some amazing As part of the national DfE funded Heritage Learning Manager projects including ‘Lancashire Sparks’ Museums and Schools Programme, we an exploration of Lancashire’s intangible are always keen to work with teachers 01772 535075 heritage through clog dancing, music and schools to develop our learning and literacy. The TIME project continues offer. Our themes for this year are STEM, to work successfully with schools Literacy and teacher development. embedding the creative arts into the curriculum. Please contact us if you The funding for Heritage Learning comes would like more information about our from a de-delegated budget which range of new school projects. schools vote to continue each year. This funding allows the team to deliver Once again our teacher CPD, twilight award winning, high quality cultural and INSET programmes have grown from learning across Lancashire.