APPENDIX D LAPD FINAL MONITOR REPORT Office of the Independent Monitor: Final Report June 11, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Best Bets

Sunday SUNDAY PRIME TIME APRIL 8 S1 – DISH S2 - DIRECTV Best Bets 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 S1 S2 WSAZ WSAZ NBC News Dateline NBC Harry's Law "The Celebrity Apprentice "Ad Hawk" A celebrity WSAZ :35 Storm 3 3 NBC News Lying Game" (N) goes on a tirade against a teammate. (N) News Stories WLPX 5:30 < Space Cowboys ('00) Tommy Lee Jones, Clint < The Visitor ('07) Haaz Sleiman, Richard Jenkins. A < Rebound ('05) ION Eastwood. NASA recruits hotshot pilots to repair a satellite. professor finds a couple living in his NY apartment. Martin Lawrence. 29 - 5:00 < Out of Bounds World's Funniest Masters of Illusion < Freeway ('96) Reese Witherspoon. A Crook and Music TV10 - - ('03) Sophia Myles. Moments troubled young girl flees the foster-care system. Chase Row WCHS Eyewit- World America's Funniest Once Upon a Time GCB "Turn the Other GCB "Sex Is Divine" Eyewit- :35 Ent. ABC ness News News Home Videos "7:15 a.m." Cheek" (N) (N) ness News Tonight 8 8 WVAH Big Bang Two and a The Cleveland The B.Burger Family American Eyewitness News at Wrestling Ring of FOX Theory Half Men Simpsons Show Simpsons "Torpedo" Guy Dad 10 p.m. Honor 11 11 WOWK 2:00 Golf Masters 60 Minutes The Amazing Race (N) The Good Wife "The CSI: Miami "Habeas 13 News Cold Case CBS Tournament (L) Death Zone" Corpse" (SF) (N) Weekend 13 13 WKYT 2:00 Golf Masters 60 Minutes The Amazing Race (N) The Good Wife "The CSI: Miami "Habeas 27 :35 CBS Tournament (L) Death Zone" Corpse" (SF) (N) NewsFirst Courtesy - - WHCP < The Addams Family A greedy lawyer < Addams Family Values The family must Met Your Met Your The King The King CW tries to plunder the family's fortune. -

Ordinance No. 2015-37

ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 ORDINANCE GRANTING AN EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE TO PROGRESSIVE WASTE SOLUTIONS OF FL., INC., A FLORIDA CORPORATION, FOR THE COLLECTION OF RESIDENTIAL MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE, AS THE COMPANY WITH THE HIGHEST RANKED BEST OVERALL PROPOSAL PURSUANT TO REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL NO. 2014-15-9500-00-002, FOR A TERM BEGINNING UPON EXECUTION OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT BY THE PARTIES AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2019, WITH AN AUTOMATIC RENEWAL TERM THEREAFTER OF FIVE YEARS, BEGINNING ON OCTOBER 1, 2019 AND ENDING ON SEPTEMBER 30, 2023, AND SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AT THE OPTION OF THE PARTIES, FOR A TERM OF ONE YEAR EACH, WITH A CUMULATIVE DURATION OF ALL SUBSEQUENT RENEWALS AFTER THE FIRST RENEWAL TERM NOT EXCEEDING A TOTAL OF FIVE YEARS; APPROVING THE TERMS OF THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE IN SUBSTANTIAL CONFORMITY WITH THE AGREEMENT ATTACHED HERETO AND MADE A PART HEREOF AS EXHIBIT '·t··; AND AUTHORIZING THE MAYOR AND THE CITY CLERK, AS ATTESTING WITNESS, ON BEHALF OF THE CITY, TO EXECUTE THE EXCLUSIVE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT; REPEALING ALL ORDINANCES OR PARTS OF ORDINANCES IN CONFLICT HEREWITH; PROVIDING PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION HEREOF; PROVIDING FOR A SEVERABILITY CLAUSE; AND PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the City issued a request for proposals ("'RFP") for certain types of Solid Waste Collection Services; and ORDINANCE NO. 2015-37 Page 2 WHEREAS, Progressive Waste Solutions of FL, Inc. ("'Progressive Waste") submitted a proposal in response to the City's RFP (RFP No. 2014-15-9500-00-002); and WHEREAS, the City has relied upon -

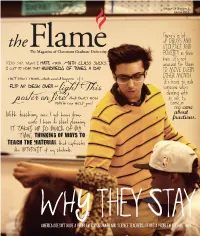

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Community and Economic Development Committee Report (Item No

~' ,,. u '•' ,,.,.,,,.,1.i!,,.: ,, , •• 0 ~Ef¥' OF' Los, ANGEL:: Office of the FRANK T. MARTINEZ .. , , CALIFORNIA L City Clerk CITY CLERK Council and Public Services KAREN E. KALFAYAN Room 395, City Hall Executive Officer Los Angeles, CA 90012 Council File Information - (213) 978-1043 General Information - (213) 978-1133 When making inquiries Fax: (213) 978-1040 relative to this matter refer to File No. HELEN GINSBURG ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA Chief, Council and Public Services Division 01-1057 MAYOR October 5, 2005 Honorable Antonio Villaraigosa Councilmember Perry. Councilmember Garcetti Councilmember Greuel Chief Legislative Analyst City Administrative Officer Controller: Room 300 Accounting Division F&A ~- Disbursement Division , City Attorney / ~. Bureau of Contract Administr~tion RE: STATUS OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ADMINISTRATION EARTHQUAKE ASSISTANCE GRANT AWARD OF 1995, THE MAYOR'S OFFICE URBAN DEVELOPMENT ACTION GRANT, AND OTHER CURRENT GRANT ACTIVITIES I At the meeting of the Council held September 20, 2005, the following action was taken: Attached report adopted, as amended............................ X Attached amending motion (Garcetti - Greuel) adopted........... X 'FORTHWITH ..................................................... ·------- Mayor concurred . 10-03-05 To the Mayor FORTHWITH ........................................ ______ Motion adopted to approve communication recommendation(s) ..... ·~~~~~~- Motion adopted to approve committee report recommendation(s) .. ·~~~~~~- _Ordinance adopted ............................................ ··~~~~~~- Ordinance number .............................................. ·~~~--~~- Publication date .............................................. ·~~~~~~- ~ ft >'Y/~ City crm \o\1o\0S AN EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY-AFFIRMATIVE ACTION EMPLOYER City Clerk '/~[GEJ.~~) Stamp CITY O EPi<;::; OFFICE 2005 SEP 22 PM ~: 09 Zill5 SEP ?2 Pii q: 07 CIT y PF LOS I~ NGELES CITY r:[~ ___P"°''/ rit\ PV L) ! -----=o=Ep=u-=T~Y SUBJECT TO MAYOR'S APPROVAL COUNCIL FILE NO. -

Religion and Popular Culture

ular ular Fall 2017 Fall Dr. Lynn S. Neal Course Texts: [email protected] Bruce Forbes & Jeffrey Mahan, eds., Religion and Popular I do not check email after 5pm Culture in America, Revised Edition [F&M] or on weekends, please plan Other readings available via Sakai accordingly. **Please bring assigned readings to each class** OH: Wed. & Fri. 11-12 Religion 267 PopReligion and Culture Course Description: “At work and at play, human In recent decades, many have predicted the demise of religion and the authenticity is at “death of God.” Indeed, many seem to embrace science and rationality stake in over faith and the supernatural, yet religion remains and permeates American American society, particularly popular culture. This raises a number of religion and questions: What is popular culture? What role is religion playing in it? Why? popular culture. How do we assess combinations of the sacred and the secular? What does Religion is the it all mean? Throughout the semester, this courses promises to answer real thing, but, as these questions by investigating four themes—religion IN popular culture, we already know popular culture IN religion, popular culture AS religion, and religion and from the world of popular culture in dialogue. These themes structure the course and advertising, Coca-Cola is also represent the dominant patterns in thinking about the popular and the the real thing.” pious. By examining numerous sources, topics, and dilemmas, from Star Trek fandom to religious games to Madonna, we’ll be investigating the ~David Chidester meaning of religion in the American religious landscape. Advice for Religion 267 wearing a The course requirements provide you with an opportunity to explore topics , and issues in more depth and are designed to help you realize the course objectives. -

Ordinance 2021-02

TOWNSHIP OF WANTAGE ORDINANCE #02-2021 AN ORDINANCE TO AMEND CHAPTER 3, POLICE REGULATIONS NOISE ORDINANCE I. Declaration of Findings and Policy WHEREAS, excessive sound is a serious hazard to the public health, welfare, safety, and the quality of life; and, WHEREAS, a substantial body of science and technology exists by which excessive sound may be substantially abated; and, WHEREAS, the people have a right to, and should be ensured of, an environment free from excessive sound. Now THEREFORE, it is the policy of Township of Wantage to prevent excessive sound that may jeopardize the health, welfare, or safety of the citizens or degrade the quality of life. This Ordinance shall apply to the control of sound originating from sources within the Township of Wantage. II. Definitions The following words and terms, when used in this Ordinance, shall have the following meanings, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise. Terms not defined in this Ordinance have the same meaning as those defined in N.J.A.C. 7:29. “Construction” means any site preparation, assembly, erection, repair, alteration or similar action of buildings or structures. “dBC” means the sound level as measured using the “C” weighting network with a sound level meter meeting the standards set forth in ANSI S1.4-1983 or its successors. The unit of reporting is dB(C). The “C” weighting network is more sensitive to low frequencies than is the “A” weighting network. “Demolition” means any dismantling, destruction or removal of buildings, structures, or roadways. “Department” means the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. “Emergency work” means any work or action necessary at the site of an emergency to restore or deliver essential services including, but not limited to, repairing water, gas, electricity, telephone, sewer facilities, or public transportation facilities, removing fallen trees on public rights -of-way, dredging navigational waterways, or abating life-threatening conditions or a state of emergency declared by a governing agency. -

HHA Board Meeting Minutes January 8, 2020 Meeting Called to Order

HHA Board Meeting Minutes January 8, 2020 Meeting called to order: 7:04 pm Attendees: Brent Gawlik, President Kathleen Haley, Marketing & Communications Rep Mike Anderson, Treasurer Ed Moore, MAHA Rep Meredith Long, Secretary Kristine Lucius, Adray Rep Lindsey Moungkhoun, Squirt Rep Jabez Waalkes, Apparel Sean Long, Peewee Rep Approval of December 2020 Meeting Minutes Motion: Ed Moore Second: Jabez Waalkes Motion Carries. Minutes to be published to website. Financial Report: Mike Anderson, Treasurer Current Balances as of 01.08.2020 . House: $ 3329.60 . Travel: $ 5687.06 . Scrip: $ 11,174.90 Uncollected Invoice Totals as of 01.08.2020; . House: Invoiced $ 57,250, Uncollected $ 35,779 (37% of fees collected) . Travel: Invoiced $ 113,805, Uncollected $ 59,434.45 . Payment solution for next year No formal registration or team appointment until first payment received No participation on house teams until first payment received 10-day grace period to submit payment at the beginning of each month before credit card is used for an auto draft December expenditures were largely ice invoices, officiating payments, and tournaments Current projected shortfall: $ 3000 Email from Brent to families through team managers for uncollected fees to be sent this week. Scrip credits ($ 9500) to be applied to all eligible accounts 01.10.2020. Anticipate 75% of monies to go towards travel accounts February Action Item: Revisit Sports Engine payment platform to create new system for 2020 Spring Hockey season: 01.08.20 Squirt Rep: Lindsey Moungkhoun Try Hockey For Free . 10 participants, half were repeats from the first THFF . Next national date: 02.22.2020 Volunteers (Lindsey) Ice Time/Book with rink: 11:00-11:50 am (Brent) Promotional Materials (Kathleen) Equipment Check for next THFF date (Board 02.05.20) MAHA Report: Ed Moore Match Penalties . -

JUN 1 0 2005 June 9, 2005 DEPUTY O

FRANK T. MARTINEZ :•ITV OF Los ANGELe.4' Office of the City Clerk CALIFORNIA CITY CLERK Council and Public Services KAREN E. KALFAYAN Room 395, City Hall · Executh·e Officer Los Angeles, CA 90012 Council File Information - (213) 978-1043 General Information - (213) 978-1133 When making inquiries Fax: (213) 978-1040 relati\'e to this matter refer to File No. HELEN GINSBURG JAMES K. HAHN Chief, Council and Public Senices Division MAYOR 01-2163 PLACE IN FILES JUN 1 0 2005 June 9, 2005 DEPUTY o/ City Administrative Officer Controller, Room 300 Attn: City Attorney Analyst Accounting Division, F&A Liability Claims/Budget Group Disbursement Division Room 1260, CHE Office of Finance City Attorney, Treasurer cc: Jennifer Krieger Councilmember Miscikowski cc: Business Office Councilmember Cardenas cc: Budget & Finance Division Los Angeles Police Department RE: SETTLEMENT OF CASE ENTITLED NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD, ET AL., V. CITY OF LOS ANGELES, ET AL., UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CASE NO. CV 01-06877 FMC (CWX) At the meeting of the Council held May 25, 2005, the following action was taken: Attached report adopted ........................................ ______ Attached motion (Miscikowski - Cardenas) adopted in open session ........ ····~~~~X=----~~- Attached resolution adopted .................................... ______ Ordinance adopted ............................................. ·~~~~~~- Motion adopted to approve attached report ...................... ______ Motion adopted to approve attached communication ........... ····~~~~~~- To the Mayor -

Lost and Found Wherever the Kam May Take Me Scattered Showers Our Own Lance Cpl

SEPTEMBER 4, 2009 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 35 WWW.MCBH.USMC.MIL Hawaii Marine DOG GONE ORDER Cpl. Danny H. Woodall Combat Correspondent recently released Marine Corps Order prohibits full or mixed breeds of Pit ABulls, Rottweilers and canid/wolf hybrids aboard Marine Corps installations. According to the order, the rise in own- ership of large dog breeds with a predispo- sition toward aggressive or dangerous behavior, coupled with the increased risk of tragic incidences involving these dogs, has prompted the commandant of the Marine Corps to issue a new change to Marine Photos by Lance Cpl. John P. Hitesman Corps Order P11000.22. The change to the Marines from Golf Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, Marine Expeditionary Brigade-Afghanistan, take cover from enemy fire during the begin- order was made to provide for the health, ning of a patrol to search the city of Dehana, Helmand province, Afghanistan during Operation Eastern Resolve II August 13. safety and tranquility of all residents of family housing areas Corpswide. There have been several fatal incidents of dog attacks on Marine Corps bases, said Island Warriors take Dehana back from Lt. Col. Jeffrey S. Tontini, base inspector. The movement to ban aggressive breeds of dogs emanated from these attacks. Taliban forces during Eastern Resolve II The order also states that a Veterinary Corps Officer or civilian veterinarian will determine the “majority breed” of a dog in They have taxed the local citizens and used Prior to Eastern Resolve II, the citizens of Lance Cpl. John P. Hitesman the absence of formal breed identification. -

Fall 2004 L a W Address Service Requested

USCLAW Nonprofit Organization University of Southern California U.S. Postage Paid U Los Angeles, California 90089-0071 University of Southern California S C UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA THE LAW SCHOOL fall 2004 L A W Address Service Requested In this issue Scott Bice in the classroom Experts discuss the 2004 election Alumni in public service USCLAW Alumni seek fall Holocaust justice 2004 USCLAW THE LAW SCHOOL fall 2004 16 20 31 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS PROFILES 12 On law and politics 02 Dean’s Message 30 Fernando Gaytan ’02 Q&A on the 2004 Skadden fellow remains election with political 03 News dedicated to public experts from USC Law Alumni achievements; service and equal justice new scholarships; research 16 Litigating loss center moves to USC; 31 Rhonda Saunders ’82 USC alumni draw attention and more Deputy district attorney to Holocaust-era theft pursues stalkers, protects 10 Quick Takes victims 20 An educator in full Class of 2007; ethics Former Dean Scott Bice ’68 training; BLSA honored; returns to the classroom and more full time 24 Faculty News Faculty footnotes; obituaries; and more 32 Closer Frances Khirallah Noble ’72 on growing up Arabic in America DEAN’S MESSAGE I’ve been talking a lot lately about one of my favorite subjects — the quality of the students at USC Law. For the past two years, our incoming classes have set new records for LSAT and GPA scores, and the upward trend shows no signs of slowing. The ascent has been dramatic: From 2001 to 2004, the median LSAT for our incoming students climbed from 164 to 166. -

Construction of a Recreation Facility at Harbor Hills

BORDER ISSUES STATUS REPORT Revised December 15, 2020 The following is a listing of the history and most recent status of all of the Border Issues that are currently being monitored by the City. PALOS VERDES PENINSULA WATER RELIABILITY PROJECT (ROLLING HILLS ESTATES, RANCHO PALOS VERDES AND UNINCORPORATED LOS ANGELES COUNTY) Last Update: December 15, 2020 California Water Service Company (CWSC) made a presentation to the City Council regarding its master plan for the Palos Verdes District on February 17, 2004. Part of this plan envisioned placing two (2) new water mains under Palos Verdes Drive North to replace an existing line serving the westerly Peninsula (the so-called “D-500 System”); and to supplement existing supply lines to the existing reservoirs at the top of the Peninsula (the so-called “Ridge System”). Another previous Border Issue upon which the City commented in 2003 was the Harbor-South Bay Water Recycling Project, proposed jointly by the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) and the West Basin Municipal Water District (WBMWD) to provide reclaimed water for irrigation purposes. One of the proposed lines for this project (Lateral 6B) would be placed under Palos Verdes Drive North to serve existing and proposed golf courses and parks in Rolling Hills Estates, Palos Verdes Estates and County territory, as well as Green Hills Memorial Park in Rancho Palos Verdes. Adding to these water line projects is a plan by Southern California Edison (SCE) to underground existing utility lines along Palos Verdes Drive North between Rolling Hills Road and Montecillo Drive. All of these projects would require construction within the public right-of-way of Palos Verdes Drive North, which is already severely impacted by traffic during peak-hour periods. -

Meeting Called to Order by SAC Chairman. Fabia Reid Introduced As New Committee Secretary; SAC Committee Back to Full Strength

14 November 2018 Meeting Minutes 1600: Meeting called to order by SAC Chairman. Fabia Reid introduced as new committee secretary; SAC Committee back to full strength. 1610: SAC Vice Chairman reviewed old business & previous minutes placing emphasis on parent questions. College night went pretty well; financial aid, among other things, was discussed. Parent Questions: 1. One grade per week policy? There is no DODEA requirement. Guidance from NMHS Principal is “timely submission of grades on Gradespeed” to provide an accurate depiction of what students’ grades are. If there is a particular concern that a parent may have, parents are encouraged to first contact their child’s teacher(s), request a conference at any time, & if necessary, contact the school Principal for final resolution.” 1b. “Part of the concern about grades referred to student athletes that travel. Reviews are completed on Tuesday, sometimes the grades aren’t reflected on Gradespeed or there is only one or a couple of grades.” The Principal offered that during a recent staff meeting, the Athletic Director specifically reviewed the eligibility requirements to identify what constitutes an eligible student at the beginning of the sport season, & what the school is required to do as far as monitoring for the next consecutive three weeks. The Athletic Director pushed to get grades “in by Friday so that they can be pulled by Tuesday because it takes a couple of hours for grades to come in.” NMHS Principal shared that “While there is some teacher responsibility, there are also responsibilities for the students to understand that work must be turned in on Friday because that is the real hard deadline.