Complex Ecological Pathways Underlie Perceptions of Conflict Between Green Turtles and Fishers in the Lakshadweep Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 2012 333333333333333333333333

Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 2012 333333333333333333333333 LAKSHADWEEP ACTION PLAN ON CLIMATE CHANGE (LAPCC) UNION TERRITORY OF LAKSHADWEEP i SUPPORTED BY UNDP Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 LAKSHADWEEP ACTION PLAN ON CLIMATE CHANGE (LAPCC) Department of Environment and Forestry Union Territory of Lakshadweep Supported by UNDP ii Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 Foreword 2012 Climate Change (LAPCC) iii Lakshadweep Action Plan on Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 Acknowledgements 2012 Climate Change (LAPCC) iv Lakshadweep Action Plan on Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 CONTENTS FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................... III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................... IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. XIII PART A: CLIMATE PROFILE .............................................................................................................. 1 1 LAKSHADWEEP - AN OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Development Issues and Priorities .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Baseline Scenario of Lakshadweep ............................................................................................................................ -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep

Socioeconomic Monitoring for Coastal Managers of South Asia: Field Trials and Baseline Surveys Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep Project completion Report: NA10NOS4630055 Project Supervisor : Vineeta Hoon Site Coordinators: Idrees Babu and Noushad Mohammed Agatti team: Amina.K, Abida.FM, Bushra M.I, Busthanudheen P.K, Hajarabeebi MC, Hassan K, Kadeeshoma C.P, Koyamon K.G, Namsir Babu.MS, Noorul Ameen T.K, Mohammed Abdul Raheem D A, Shahnas beegam.k, Shahnas.K.P, Sikandar Hussain, Zakeer Husain, C.K, March 2012 This volume contains the results of the Socioeconomic Assessment and monitoring project supported by IUCN/ NOAA Prepared by: 1. The Centre for Action Research on Environment Science and Society, Chennai 600 094 2. Lakshadweep Marine Research and Conservation Centre, Kavaratti island, U.T of Lakshadweep. Citation: Vineeta Hoon and Idrees Babu, 2012, Socioeconomic Monitoring and Assessment for Coral Reef Management at Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep, CARESS/ LMRCC, India Cover Photo: A reef fisherman selling his catch Photo credit: Idrees Babu 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Acknowledgements 8 Glossary of Native Terms 9 List of Acronyms 10 1. Introduction 11 1.1 Settlement History 11 1.2 Dependence on Marine Resources 13 1.3 Project Goals 15 1.4 Report Chapters 15 2. Methodology of Project Execution 17 2.1 SocMon Workshop 17 2.2 Data Collection 18 2.3 Data Validation 20 3. Site Description and Island Infrastructure 21 3.1 Site description 23 3.2. Community Infrastructure 25 4. Community Level Demographics 29 4.1 Socio cultural status 29 4.2 Land Ownership 29 4.3 Demographic characteristics 30 4.4 Household size 30 4.5. -

Technical Report on Design and Execution of Desalination Plants in Minicoy and Agatti, UT Lakshadweep

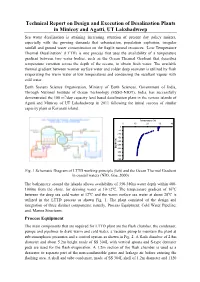

Technical Report on Design and Execution of Desalination Plants in Minicoy and Agatti, UT Lakshadweep Sea water desalination is attaining increasing attention of present day policy makers, especially with the growing demands that urbanization, population explosion, irregular rainfall and ground water contamination on the fragile natural resources. ‘Low Temperature Thermal Desalination’ (LTTD) is one process that uses the availability of a temperature gradient between two water bodies, such as the Ocean Thermal Gradient that describes temperature variation across the depth of the oceans, to obtain fresh water. The available thermal gradient between warmer surface water and colder deep seawater is utilized by flash evaporating the warm water at low temperatures and condensing the resultant vapour with cold water. Earth System Science Organization, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, Through National Institute of Ocean Technology (ESSO-NIOT), India, has successfully demonstrated the 100 m3/day capacity land based desalination plant in the remote islands of Agatti and Minicoy of UT Lakshadweep in 2011 following the initial success of similar capacity plant at Kavaratti island. Temperature (oC) 0 10 20 30 40 0 -50 -100 -150 -200 -250 Depth (m) Depth -300 -350 -400 -450 Fig. 1 Schematic Diagram of LTTD working principle (left) and the Ocean Thermal Gradient in coastal waters (NIO, Goa, 2000) The bathymetry around the islands allows availability of 350-380m water depth within 400- 1000m from the shore, for drawing water at 10-12oC. The temperature gradient of 16oC between the deep sea cold water at 12oC and the warm surface sea water at about 28oC is utilized in the LTTD process as shown Fig. -

1 Government of India Lakshadweep Administration (DEPARTMENT OF

THE LAKSHADWEEP GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY 1 VOL. LVI. No. 28 THURSDAY 15th OCTOBER, 2020 / 23rd ASVINA, 1942 (SAKA) Government of India Lakshadweep Administration (DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND FOREST) Kavaratti Island, Dated : 14-10-2020. NOTIFICATION F.No. 2/22/2020-E&F:- The Administrator, Union Territory of Lakshadweep Administration is pleased to publish the Lakshadweep Forest Code-2020 of the Department of Environment and Forest, Union Territory of Lakshadweep Administration and is declared as the Official Forest Code of the department with effect from the date of publication of this notification in the Official Gazette. This is issued with the approval of Hon’ble Administrator vide Diary No. 1752, dated 07-10-2020. Sd/- (DAMODHAR A.T., IFS) Secretary, Environment & Forest and Chief Wildlife Warden. LGP.Kvt. G-1389/10 -20/50 PRICE: 75 PAISE 2 THE LAKSHADWEEP GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY CHAPTER – I ORGANISATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND FOREST 1 – GENERAL 1.1 Introduction Natural ecosystems are a dynamic ecosystem consisting of plants, animals & microorganisms safeguarding the ecological security of the nation. It provides various ecosystem services essential for the very survival of the human beings. The aim of the Department of Environment & Forest in UT of Lakshadweep is department and services ensure environmental stability and maintenance of ecological balance including atmospheric equilibrium which are vital for sustenance ofall life forms, human, animals and plants. This policy will be instrumental in strengthening ecological security, sustainable ecological management, and participatory management. This also ensures to safeguard the ecological and livelihood security of people, of the present and future generations, based on sustainable management of the ecosystem services thereby the stability of the fragile eco-systems. -

Human Impacts on Lakshadweep Atolls, India

HUMAN IMPACTS ON LAKSHADWEEP ATOLLS, INDIA Abstract coconuts per year. There are about 6200 fishermen The Lakshadweep (Laccadive) islands are situated engaged in fishing using 900 boats. The total fish in the Arabian Sea about 225 to 450 km from the landings in these islands per year are about 15000 tonnes. southwest coast of India. These islands situated 1 to 2 The people are dependent on the mainland for all meters above mean sea level has a very thin lens of fresh essential supplies including fuel, vegetables, packaged water floating over the seawater. Almost all fresh water foods, and infrastructure. sources are contaminated due to seawater intrusion. The Lakshadweep islands are lying along a north-south drinking water wells contain excessive nitrate axis (except Androth Island) with lagoon on the west and concentration originating from septic tanks, other human open sea on the east. Estimated total coral reef area in wastes and fertilizers used in garden. All drinking water these islands is 276 km2 including the reef flat area of sources show positive bacterial (faecal coliform) count 136.5 km2 (Bahuguna and Nayak, 1998). Taxonomic exceeding the normal level. Increasing population studies of Lakshadweep corals are almost restricted to pressure (2600 people / km2) leading to the accumulation the pioneering works of Pillai (1989) and he showed the of more diseases in corals. The newly emerging disease presence of 104 species under 37 genera. The extensive Red Plague Syndrome is spreading very fast in these surveys made by the author during the year 2002 to 2003 islands. The anthropogenic impacts on coral reefs are and the results showing additional 9 species were present discussed in the paper in detail. -

COVID 19 Situation in Lakshadweep Islands

Vol. * XXXVI. No. 09 * KAVARATTI *WEDNESDAY * 23 JUNE 2021. Price Rs. 2. Hon'ble Administrator Collector and Chairman Shri Praful Patel District Disaster Manage- A COVID patient evacuating visited Lakshadweep and ment Authority Shri S. from Chetlat by Ambulance discussed various Asker Ali, IAS chairing a helicopter. developmental activities of meeting at Agatti Island. the territory. COVID 19 Situation in Hon'ble Administrator visited Lakshadweep Islands Lakshadweep 28th December, 2020, Collector said. Following the revised SOP, livelihood activities resumed in the islands. 945 tourists visited the islands in the five months since SOP was revised. Mechanized sailing vessels operated in the islands for 380 times. Consequently, construction activities A view from the COVID test at Kavaratti. started in the islands. Kavaratti : Due to the considering the genuine Flight operations were COVID 19 pandemic, requirement of the local also resumed. During this Lakshadweep islands population in terms of period, 35,170 people had highly restricted livelihood activities, came from mainland to Hon'ble Administrator Shri Praful Patel chairing a meeting conducted at movement of men and developmental islands majority of them Secretariat Conference Hall, Kavaratti. are local population and material from the mainland requirements of the local people in the to safeguard and protect considered, then 92,231 people travelled by to the islands and vice Administration and the islands also contributed its citizens from the Lakshadweep ships and HSC within versa from March prevailing MHA Guidelines significantly to the rise of pandemic. As a result of Administration has Lakshadweep islands, he to December 2020. during that time. As per COVID 19 cases in such continuous efforts, vaccinated 97.16% of its said. -

THE LAKSHADWEEP TIMES Vol

THE LAKSHADWEEP TIMES Vol. * XXXV. No. 22 * KAVARATTI *FRIDAY * 23 OCTOBER 2020. Price Rs. 2. TOP STORIES Advisor to Hon’ble Administrator and Indigenously built stealth High Level Officials Visited Agatti Island corvette INS Kavaratti commissioned into Indian Navy Chief of Army Staff Gen MM Naravane commissioned the last of four indigenously built Advisor to Hon’ble Administrator and high level officials of Advisor to Hon’ble Administrator and high level officials hearing anti-submarine warfare UT Administration is being received by Deputy grievances from public at Agatti. (ASW) stealth corvettes Collector,Chairperson,VDP and others. ‘INS Kavaratti’ into the Agatti: Shri. P. During the visit at Households. He also needy requirements. E-Hospital, Oxygen plant Indian Navy in Krishnamurthy, Advisor to Agatti, the Advisor to inaugurated the Lobster While interacting with etc. He also directed to Visakhapatnam on concerned the increase Thursday. Hon’ble Administrator and Hon’ble Administrator and Holding and Fattening Deputy Collector, the contingent fund and Army Chief General high level officials of UT his team visited various Cages-Plot Farm Chairperson VDP, Manoj Mukund Administration visited places like Govt. Senior established at Agatti Administrative Officer speed up the annual Naravane said, “The Agatti Island on 17th Secondary School, Coir jointly by the Department RGSH and Manager procurement of OPD commissioning of INS October 2020. Production Centre, of Fisheries, UTL and DAYA, Advisor to Hon’ble medicines. Kavaratti marks yet Smt. A.M. Kadeeshabi, Western Side Jetty, ICAR-CMFRI sponsored Administrator has given While visiting Govt. another significant step Deputy Collector and Smt Agriculture plot, Rajiv by NFDB GOI by putting directions to concerned Senior Secondary School, in securing our country’s A. -

Storage of Solar Power for Micro Grids in the Islands of Andaman

Storage of Solar power for Micro Grids in the Islands of Andaman & Nicobar, as well as Lakshadweep JOINT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION For the State of Goa and Union Territories These are Renewable Energy deficient areas (poor Capacity Utilization Factor & Low Solar Insolation). Further, these areas mostly being Coastal /Islands are tourist attraction and are having land constraint for Ground Mounted Solar Installation. Details of various areas under the jurisdiction of this Commission are: Sl. Location Latitude Longitude Remarks 1. Andaman & Nicobar 11.68° N 92.77° E Islands, Not Connected to National Grid, 1000 Kms from Mainland, Tourists place. The Power is Generated by Diesel and is thus very expensive. 2. Lakashadweep 10° 00' N 73.00° E Islands, Not Connected to National Grid, 300 Kms. from Mainland Tourists place. The Power is Generated by Diesel and is thus very expensive. Other Territories under the Jurisdiction of the Commission 3. Goa 15.4989° N 73.8278° E Coastal, Tourists Place 4. Chandigarh 30.75° N 76.78° E Non Coastal, Small Area, Pollution free area 5. Dadra & Nagar Haveli 20.27° N 73.02° E Highly Industrialized 95% Power Consumption by Industry, Highest Per Capita Power Consumption in India because of Industry 6.a Daman 20° 25' N 72°.53° E Coastal, High concentration of Industry 6.b Diu 20° 42' N 71.01° E Tourists Place, Coastal 7.a Puducherry- Puducherry 11.93° N 79.83° E Tourists, Coastal 7.b Karaikal- Puducherry 10° 55' N 79. 52° E Tourists, Coastal 7.c Mahe- Puducherry 11.7011° N 75.5367° E Tourists, Coastal 7.d Yanam- Puducherry 16.7333° N 82.25° E Tourists, Coastal The Joint Electricity Regulatory Commission (JERC) is pushing for Solar Roof Tops in all the seven territories. -

Indian Army 13

Annual Report 2016-17 Ministry of Defence Government of India Contents 1. Security Environment 1 2. Organisation and Functions of the Ministry of Defence 7 3. Indian Army 13 4. Indian Navy 25 5. Indian Air Force 35 6. Indian Coast Guard 43 7. Defence Production 51 8. Defence Research and Development 73 9. Inter Service Organisations 93 10. Recruitment and Training 115 11. Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 137 12. Cooperation between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 149 13. National Cadet Corps 157 14. Defence Cooperation with Foreign Countries 167 15. Ceremonial and Other Activities 177 16. Activities of Vigilance Units 189 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 197 Appendices I Matters dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 205 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in Position from 209 January 1, 2016 onwards III Summary of Important Audit Observations-Ministry of Defence 211 IV Position of Action Taken Notes (ATNs) as on 31.12.2016 in respect of 217 observations made in the C&AG Reports/PAC Reports 1 SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Chapter 1 Security Environment 1.1 Given the prevailing uncertainties and and challenges to norms of international law challenges in the international security scenario, as well as standards of international behaviour. India’s national security imperatives as well as The rise of nationalism, including in key its growing regional and global role necessitate Western nations, and continued challenges to a strong and dynamic engagement in defence democratic structures and processes in several and security cooperation with friendly foreign countries, could limit the efficacy of efforts for countries. -

The Tourism Survey for Lakshadweep Final Report (Oct 2017 - June 2018) for Market Research Division, Ministry of Tourism Government of India By

The Tourism Survey For Lakshadweep Final Report (Oct 2017 - June 2018) For Market Research Division, Ministry of Tourism Government of India By ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We are thankful to the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India for assigning this Study on Tourism Survey for Lakshwadeep. We are grateful to Shri Yogendra Tripathi, Secretary (Tourism), and Shri Satyajeet Rajan, Director General (Tourism) for extending their support. We are also grateful to Shri P.C. Cyriac Additional Director General (MR), Smt. Mini Prasanna Kumar, Director (MR), Ms. Aqsa Ilahi Deputy Director (MR), for providing us the necessary guidance and periodical support for conducting the study. We would also like to thank Shri S.K. Mahanta, Programmer (MR) for providing us the required support and help from time to time. We are also thankful to Shri A. Hamza, Secretary (Tourism), Lakshwadeep and other State Tourism Officials for extending their help and support from time to time. Last but not the least we would like to thank our entire team of research professionals as well as our field team for keeping up the momentum and time schedule of the study. Executive Summary - Lakshadweep 2017-18 Tourism Survey Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ii Report For The State of Lakshadweep 1 Report for Kavaratti 19 Report for Agatti 37 Report for Kadmat 55 Report for Bangaram 73 Report for Thinnakara 91 Annexure 1 : Methodology 109 Annexure 2 : Estimation Procedure 115 Annexure 3 : Questionnaires / Survey Instruments 124 Executive Summary - Lakshadweep 2017-18 Tourism Survey Page iii Executive Summary E.1 Tourism in Lakshadweep Lakshadweep, formerly known as the Laccadive, Minicoy, and Amindivi Islands is a group of islands in the Laccadive Sea, 200 to 440 km off the South Western coast of India. -

Urbanisation and Socio-Economic Structure in Lakshadweep

International Journal of Research in Geography (IJRG) Volume 3, Issue 3, 2017, PP 30-37 ISSN 2454-8685 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0303003 www.arcjournals.org Urbanisation and Socio-Economic Structure in Lakshadweep Joginder Extension Faculty, Pt. Neki Ram Sharma Government College, Rohtak Abstract: Lakshadweep is located in the western part off mainland India in Arabian Sea. It is believed that initially the islands were inhabited by the Malayalis in ninth century. However, the territory remained less fascinating to the outsiders. The people of the region were isolated from the world mainstream and witnessed many upheavals. Hence, the developmental activities were very little before 1956 when the control of the islands comes to Indian Government. Thereafter, the islanders got the status of tribe and the impetus of developmental activities took place on the inhabited islands. The region is composed of calcareous soil due to the formation of the islands by coral reefs which unfertile for agricultural activities except plantation activities. Coconut and papaya cultivation are the main mainstay of the islanders. The industrial development is also low. Hence, the social and economic condition of families in the region is poor. Consequently, the survival and livelihood of the tribal people depends upon the extraction of copra, collect cowry, fishing and so on as their economic pursuits on the islands. Various social, economic, infrastructure and agriculture development plans have been initiated by the government of India in the region. The present paper tries to study the demographic, social and economic structure of the population in the urban areas on the Lakshadweep islands.