Don't See, Don't Speak a Collection of Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gorgeous with a Side of Desire

GORGEOUS WITH A SIDE OF DESIRE J.D. BLACKROSE 1 melia placed her hands on her hips and gave Lissa the beady eyeball. "You're thinking about Mike again, A aren't you? You could have anybody if you put your‐ self out there, but you squirrel yourself away in a corner office. There has to be more to life than work and your cat." "And my dad." "And your father," Amelia conceded. "But I don't understand why you're hiding. You're beautiful and smart. You're the head of Fall City Hospital's entire Communications and Public Relations department, and a confident, professional woman, but one man looks at your big blue eyes and lovely blonde hair with interest and you flinch. Why?" “You forget that love fades quickly, Amelia.” She kept her voice mild. "Bullshit, if you'll pardon my bluntness. Mike left to pursue his passion, and he was always honest with you about that. He’s embedded in some military unit reporting under fire and that’s all he ever wanted. Besides, it would have been cruel to marry you and then take off for months and years as a combat reporter. You’d spend all your time worrying.” “You’re right, but…” “Arizona.” 1 J.D. BLACKROSE Lissa dropped her head to stare at her desk. “Arizona.” She and Mike had shared an experience in Arizona that she still couldn’t explain to this day, but she’d hoped that it had been enough to keep him stateside, with her. She’d been a fool. -

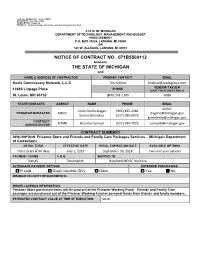

Notice of Contract No. 071B5500112 the State Of

Form No. DTMB-3522 (Rev. 2/2015) AUTHORITY: Act 431 of 1984 COMPLETION: Required PENALTY: Contract change will not be executed unless form is filed STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TECHNOLOGY, MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET PROCUREMENT P.O. BOX 30026, LANSING, MI 48909 OR 525 W. ALLEGAN, LANSING, MI 48933 NOTICE OF CONTRACT NO. 071B5500112 between THE STATE OF MICHIGAN and NAME & ADDRESS OF CONTRACTOR PRIMARY CONTACT EMAIL Keefe Commissary Network, L.L.C Tim Nichols [email protected] VENDOR TAX ID # PHONE 10880 Linpage Place (LAST FOUR DIGITS ONLY) St. Louis, MO 63132 (800) 541‐1700 ‐6999 STATE CONTACTS AGENCY NAME PHONE EMAIL dodds‐ Cindy Dodds‐Dugan (906) 495‐2282 PROGRAM MANAGERS MDOC [email protected] Eames Groenleer (517) 780‐6076 [email protected] CONTRACT ADMINISTRATOR DTMB Brandon Samuel (517) 284‐7025 [email protected] CONTRACT SUMMARY DESCRIPTION: Prisoner Store and Friends and Family Care Packages Services – Michigan Department of Corrections INITIAL TERM EFFECTIVE DATE INITIAL EXPIRATION DATE AVAILABLE OPTIONS Three years & 90 days July 1, 2015 September 30, 2018 Two‐one year options PAYMENT TERMS F.O.B. SHIPPED TO Net 45 Destination Required MDOC locations ALTERNATE PAYMENT OPTIONS EXTENDED PURCHASING ☐ P-card ☐ Direct Voucher (DV) ☐ Other ☐ Yes ☒ No MINIMUM DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS: MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION: Prisoner Store purchased items will be paid out of the Prisoner Working Fund. Friends and Family Care packages are purchased out of the Prisoner Working Fund or personal funds from friends and family members. ESTIMATED CONTRACT VALUE AT TIME OF EXECUTION: $0.00 Notice of Contract #: 071B5500112 For the Contractor: ___________________________________ __________________ Tim Nichols, Date Contract Administrator Keefe Commissary Network, L.L.C. -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski ppedDancing MyQueen Rating ABBA LocationBenny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3715072 231 1 1 1 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 1Knowing Dancing me, Queen.mp3 knowing you ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 3885158 241 1 1 2 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 2Take Knowing a chance me, knowingon me you.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 3924028 244 1 1 3 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:56 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverMamma mia Gold I:03 ABBA Take a Bennychance Andersson/Björn on me.mp3 Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3428328 213 1 1 4 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:59 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverLay all Goldyour I:04love Mammaon me mia.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 4401337 274 1 1 5 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 5Super Lay alltrouper your love ABBA on me.mp3 Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 4081599 254 1 1 6 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBAI -

Brown Overtakes Lee in Sheriff Race

Holmes County’s HOLMES COUNTY Vincent Sapp has tow boat named for him imes A4 T dvertiser Wednesday,A AUGUST 22, 2012 www.bonifaynow.com Volume 122, Number 19 50¢ For the latest breaking news, visit Brown overtakes Lee in sheriff race BONIFAYNOW.COM By CECILIA SPEARS halt and Steve Herrington III for county IN BRIEF 547-9414 | @WCN_HCT commissioner, District 1; Sasnett with 768, [email protected] Aronhalt 581 and Herrington 360. HCHS to distribute David Whiter overcame Jerry Cooley BONIFAY — Dozens gathered at the Hol- for county commissioner, District 3 by 133 2012 yearbooks mes County Supervisor of Elections of- votes, with a vote of 947 to 814. BONIFAY — Holmes fi ce, waiting late and even enduring rain For county commissioner, District County High School to hear the results of this year’s Holmes 5, Bill Parish came out on top with 1,743 will distribute 2012 County Primary Elections. votes, 853 more than the runner-up, Ron yearbooks on Friday. For sheriff, Tim Brown overtook Den- Monk, with 890, followed by Harold Smith Graduated seniors of nis Lee by 269 votes, with a vote of 1,030 with 843 votes, Wayne Marsh with 734 and 2012 may pick theirs to 761. Kristen Marell with 503. up in the student center Kyle Hudson defeated Lee Moss and Eddie Dixon surpassed Buddy Brown at 2 p.m. All graduates Zachary R. White for clerk of the circuit for superintendent of schools by 142 votes, must sign in at the court, Hudson with 1,350 votes, Moss with 1,487 to 1,345. -

Student Workbook

Student Workbook Student Workbook VVeetteerriinnaarryy SScciieennccee Illustrated by Elisabeth A. Martinec & Reka Janosi The Veterinary Science instructional unit was developed through a collaborative effort of The National Council for Agricultural Education and Cornell University as a special project of the National FFA Foundation. This curriculum has been developed as a full year course for high school students studying veterinary science with an emphasis on math and science. It is recommended that students have a background in biology and small animal care prior to taking this course. Published and Distributed by: Cornell Educational Resources Program College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Department of Education 420 Kennedy Hall Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853 © Cornell University 2003* *Cornell University has granted a worldwide license to use and distribute the Veterinary Science instructional unit to The National Council for Agricultural Education. Partial funding to support this project was provided by Ag Tech Prep Consortium sponsored by a VTEA grant from the New York State Education Department. Sponsored by Teachers have permission to duplicate the information found of the CD-ROM for use in their classrooms to benefit their students. These materials can not be duplicated for commercial purposes without the direct and expressed written permission from Cornell University. In these cases a royalty fee must be paid to Cornell. Contact Janet Hawkes (607)255-8122, for commercial duplication permissions. Notice: The information presented in this publication reflects current veterinary practices to the best of our knowledge. Readers are advised to be aware of local protocols, the needs and circumstances of individual cases, and their responsibility to stay abreast of emerging knowledge and procedures. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

First Amended Complaint for Federal Copyright

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 45 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ARISTA RECORDS LLC; ATLANTIC RECORDING CORPORATION; BMG MUSIC; CAPITOL RECORDS, INC.; ELEKTRA ENTERTAINMENT GROUP INC.; INTERSCOPE RECORDS; LAFACE RECORDS LLC; ECF CASE MOTOWN RECORD COMPANY, L.P.; PRIORITY RECORDS LLC; SONY BMG MUSIC FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR ENTERTAINMENT; UMG RECORDINGS, INC.; FEDERAL COPYRIGHT VIRGIN RECORDS AMERICA, INC.; and INFRINGEMENT, COMMON LAW WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT, Plaintiffs, UNFAIR COMPETITION, CONVEYANCE MADE WITH v. INTENT TO DEFRAUD AND UNJUST ENRICHMENT LIME WIRE LLC; LIME GROUP LLC; MARK GORTON; GREG BILDSON, and M.J.G. LIME 06 Civ. 05936 (GEL) WIRE FAMILY LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, Defendants. Plaintiffs hereby allege on personal knowledge as to allegations concerning themselves, and on information and belief as to all other allegations, as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs are record companies that produce, manufacture, distribute, sell, and license the vast majority of commercial sound recordings in this country. Defendants' business, operated under the trade name "LimeWire" and variations thereof, is devoted essentially to the Internet piracy of Plaintiffs' sound recordings. Defendants designed, promote, distribute, support and maintain the LimeWire software, system/network, and related services to consumers for the well-known and overarching purpose of making and distributing unlimited copies of Plaintiffs' sound recordings REDACTED VERSION - COMPLETE VERSION FILED UNDER SEAL Dockets.Justia.com without paying Plaintiffs anything. Plaintiffs bring this action to stop Defendants' massive and daily infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights. 2. The scope of infringement caused by Defendants is staggering. Millions of infringing copies of Plaintiff s sound recordings have been made and distributed through LimeWire — copies that can be and are permanently stored, played, and further distributed by Lime Wire's users. -

Just As Long As We're Together - Blume, Judy

Just as Long as We're Together - Blume, Judy. 1. Hunks. "Stephanie is into hunks," my mother said to my aunt on Sunday afternoon. They were in the kitchen making potato salad and I was stretched out on the grass in our yard, reading. But the kitchen window was wide open so I could hear every word my mother and aunt were saying. I wasn't paying much attention though, until I heard my name. At first I wasn't sure what my mother meant by Stephanie is into hunks, but I got the message when she added, "She's taped a poster of Richard Gere on the ceiling above her bed. She says she likes to look up at him while she's trying to fall asleep at night." "Oh-oh," Aunt Denise said. "You'd better have a talk with her." "She already knows about the birds and the bees," Mom said. "Yes, but what does she know about boys?" Aunt Denise asked. It so happens I know plenty about boys. As for hunks, I've never known one personally. Most boys my age-and I'm starting seventh grade in two weeks-are babies. As for my Richard Gere poster, I didn't even know he was famous when I bought it. I got it on sale. The picture must have been taken a long time ago because he looks young, around seventeen. He was really cute back then. I love the expression on his face, kind of a half-smile, as if he's sharing a secret with me. -

Mclachlan ICAD2012.Pdf (1.994Mb)

Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Auditory Display, Atlanta, GA, USA, June 18-21, 2012 THE SOUND OF MUSICONS: INVESTIGATING THE DESIGN OF MUSICALLY DERIVED AUDIO CUES , 2 Ross McLachlan , Mar/lyn McGee-Lennon and Stephen Brewster 2 Glasgow Interact/ve Systems Group, School of Comput/ng Sc/ence, Un/vers/ty of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ 1 2 r. mclach lan. 1 @research. gla. ac. u k , [first. [email protected] ABSTRACT subject/ve preferences /nto account we could beg/n to automate the creation process based on a user's music collection. It m/ght also be des/rable to explo/t any ex/st/ng relat/on- Mus/cons (br/ef samples of well-known mus/c used /n aud/tory sh/ps and emot/ve memor/es users may have w/th the/r own /nterface des/gn) have been shown to be memorable and easy to mus/c tracks to enable the creat/on of more personal/zed learn. However, l/ttle /s known about what actually makes a Mus/cons. A Mus/con personal/zed to a user m/ght be more good Mus/con and how they can be created. Th/s paper reports conf/dent/al to that user, eas/er to learn and/or remember. Un- on an emp/r/cal user study (N=15) explor/ng the recogn/t/on rate derstand/ng more about how best to create these more personal- and preference rat/ngs for a set of Mus/cons that were created by allow/ng users to self-select 5 second sect/ons from (a) a selec- /zed Mus/cons and how well they are recogn/zed and/or rated subject/vely w/ll prov/de some much needed groundwork /n t/on of the/r own mus/c and (b) a set of control tracks. -

Reading Sample

Lou Bihl Y’s Revenge A Novel Y's Revenge is an exclusively fictitious story and any resemblances with real events or persons are coincidental. As long as you live, nothing is final Arnold Zweig First edition 2021 © 2021 Unken Verlag GmbH, Karlsruhe Cover design : Daniel Horowitz, Paris Typesetting: Buch & media GmbH, Munich Set from the: Neuton and Segoe Printing and processing: CPI books, Leck Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-949286-01-8 www.unken-verlag.de ® www.fsc.org MIX Papier aus ver- antwortungsvollen Quellen FSC® C083411 Berlin This time, she avoided my eyes. “Professor Wolff will be with you in a minute.” The secretary of the Department of Urology guided me to the office of her boss. A moment later, Wolff rushed in and lounged his big body in the leather armchair. He poured two glasses of water from a crys- tal carafe and handed one over the table. “Sorry,” he said. “It turns out that it is not prostatitis but prostate cancer after all. I took the glass and put it down. “Good match with the weather,” I heard myself say. I stared at the giant raindrops splashing at the windowpane. “Weather will pass by,” Wolff muttered and pressed the print button of his computer. “Thanks for the awesome comfort. Life will pass by as well.” I kept on gazing at the window and watched the pouring rain. The laser printer ejected a sheet of paper. “Sorry, didn’t mean that.” Wolff handed the page over to me. I read: Prostate biopsy Prof. Dr. Kristian Starck, Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate cT2c, Grade 3 (ISUP). -

October 2020 TABLE of CONTENTS

October 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTS .............................................................................................................. 36 Beverages ............................................................................................................... 37 Coffee ................................................................................................................................................... 37 Creamers ............................................................................................................................................... 39 Drink Mix ............................................................................................................................................... 40 Drinks ................................................................................................................................................... 47 Tea ....................................................................................................................................................... 48 Food ........................................................................................................................ 49 Candy .................................................................................................................................................... 49 Cereal Bars ............................................................................................................................................ 60 Cereals .................................................................................................................................................