Copyright by Michael David Ging May 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtuosity and Technique in the Organ Works of Rolande Falcinelli

Virtuosity and Technique in the Organ Works of Rolande Falcinelli A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Loretta Graner BM, University of Kansas, 1984 MM, University of Kansas, 1988 April 2014 Committee Chair: Michael Unger, DMA ABSTRACT This study considers Rolande Falcinelli’s cultivation of technique and virtuosity as found in her organ methods and several of her organ works which have been evaluated from a pedagogical perspective. Her philosophical views on teaching, musical interpretation, and technique as expressed in three unpublished papers written by the composer are discussed; her organ methods, Initiation à l’orgue (1969–70) and École de la technique moderne de l’orgue (n.d.), are compared with Marcel Dupré’s Méthode d’orgue (pub. 1927). The unpublished papers are “Introduction à l’enseignement de l’orgue” (n.d.); “Regard sur l’interprétation à l’orgue,” (n.d.); and “Panorama de la technique de l’orgue: son enseignement—ses difficultés—son devenir” (n.d.). The organ works evaluated include Tryptique, Op. 11 (1941), Poèmes-Études (1948–1960), and Mathnavi, Op. 50 (1973). ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have given generously of their time and resources to help me bring this document to fruition, and I am filled with gratitude when I reflect on their genuine, selfless kindness, their encouragement, and their unflagging support. In processions, the last person is the most highly honored, but I cannot rank my friends and colleagues in order of importance, because I needed every one of them. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

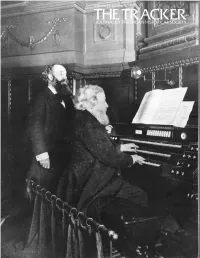

Historical Organ-Recitals

Hl~ I LLNO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Brittle Books Project, 2011. COPYRIGHT NOTIFICATION In Copyright. Reproduced according to U.S. copyright law USC 17 section 107. Contact dcc(&Iibrary.uiuc.edu for more information. This digital copy was made from the printed version held by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It was made in compliance with copyright law. Prepared for the Brittle Books Project, Preservation Department, Main Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign by Northern Micrographics Brookhaven Bindery La Crosse, Wisconsin 2011 . , . ' . OF THE UN IVERS ITY Of ILLINOIS M-76.8G.. 6G4lI music i OF THE JOSEPH BNNET H ISTORICAL O RG.AN-RECITALS IN FIVEVOLUMES iForerunnersof Bach- 2Joan n Sebastian Bac 4.Roman ero:Schu- 3'Handel, .. Mozart, and- mann, Mendelssoh'n, Liszt' Mlastrsofthe.,XVIIIhA SM ern Csar anderl Ith- centure Fran~k toMax.Reger Pice,each,$.00 Eited, an nnotated by JOSEPH;BONET Organist..ofq t . Eustache aris. -,and of: La So ci ettides Concer ts: du-Consgrvatoire. G. SlCH.JEIRMER.. INC . NEW '.YORK JOSEPH BONNET HISTORICAL ORGAN-RECITALS IN FIVE VOLUMES VOL. V Modern Composers: Cesar Franck to Max Reger Eighteen Pieces for Organ Collected, Edited and Annotated by JOSEPH BONNET Organist of St. Eustache, Paris and of La Sociti des Concerts du Conservatoire G. SCHIRMER INC., NEW YORK Copyright, 1929, by G. Schirmer, Inc. 33517 Printed in the U. -S. A. To MR. LYNNWOOD FARNAM. PREFACE It will always be a matter of regret to the organistic world that Beethoven's genius did not lead him to write for the organ. -

Maurice Duruflé Requiem Joseph Jongen Mass

Joseph Jongen Mass Maurice Duruflé Requiem San Francisco Lyric Chorus Robert Gurney, Music Director Jonathan Dimmock, Organ Saturday, August 23 & Sunday, August 24, 2014 Mission Dolores Basilica San Francisco, California San Francisco Lyric Chorus Robert Gurney, Music Director Board of Directors Helene Whitson, President Julia Bergman, Director Karen Stella, Secretary Jim Bishop, Director Bill Whitson, Treasurer Nora Klebow, Director Welcome to the Summer 2014 Concert of the San Francisco Lyric Chorus. Since its formation in 1995, the Chorus has offered diverse and innovative music to the community through a gathering of singers who believe in a commonality of spirit and sharing. The début concert featured music by Gabriel Fauré and Louis Vierne. The Chorus has been involved in several premieres, including Bay Area composer Brad Osness’ Lamentations, Ohio composer Robert Witt’s Four Motets to the Blessed Virgin Mary (West Coast premiere), New York composer William Hawley’s The Snow That Never Drifts (San Francisco premiere), San Francisco composer Kirke Mechem’s Christmas the Morn, Blessed Are They, To Music (San Francisco premieres), and selections from his operas, John Brown and The Newport Rivals, our 10th Anniversary Commission work, the World Premiere of Illinois composer Lee R. Kesselman’s This Grand Show Is Eternal, Robert Train Adams’ It Will Be Summer—Eventually and Music Expresses (West Coast premieres), as well as the Fall 2009 World Premiere of Dr. Adams’ Christmas Fantasy. Please sign our mailing list, located in the foyer. The San Francisco Lyric Chorus is a member of Chorus America. We are recording this concert for archival purposes Please turn off all cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices before the concert Please, no photography or audio/video taping during the performance Please, no children under 5 Please help us to maintain a distraction-free environment. -

Louis Vierne's Pièces De Fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55

LOUIS VIERNE’S PIÈCES DE FANTAISIE, OPP. 51, 53, 54, AND 55: INFLUENCE FROM CLAUDE DEBUSSY AND STANDARD NINETEENTH-CENTURY PRACTICES Hyun Kyung Lee, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Jesse Eschbach, Major Professor Charles Brown, Related Field Professor Steve Harlos, Committee Member Justin Lavacek, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies of the College of Music Warren Henry, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Lee, Hyun Kyung. Louis Vierne’s Pièces de Fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55: Influence from Claude Debussy and Standard Nineteenth-Century Practices. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2016, 47 pp., 2 tables, 43 musical examples, references, 23 titles. The purpose of this research is to document how Claude Debussy’s compositional style was used in Louis Vierne’s organ music in the early twentieth century. In addition, this research seeks standard nineteenth-century practices in Vierne’s music. Vierne lived at the same time as Debussy, who largely influenced his music. Nevertheless, his practices were varied on the basis of Vierne’s own musical ideas and development, which were influenced by established nineteenth-century practices. This research focuses on the music of Louis Vierne’s Pièces de fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55 (1926-1927). In order to examine Debussy’s practices and standard nineteenth-century practices, this project will concentrate on a stylistic analysis that demonstrates innovations in melody, harmony, and mode compared to the existing musical styles. -

Music for Grand Organ and Orchestra the Opening Concert of the Albert Schweitzer Organ Festival Hartford Friday, September 27, 2019, 8:00 P.M

Music for Grand Organ and Orchestra The Opening Concert of the Albert Schweitzer Organ Festival Hartford Friday, September 27, 2019, 8:00 p.m. and Sunday, September 29, 2019, 3:00 p.m. Trinity College Chapel, Hartford, Connecticut The Hartford Symphony Orchestra Carolyn Kuan, Music Director Christopher Houlihan, organ John Nowacki, narrator Program Notes By Alan Murchie Charles-Marie Widor (Born February 21, 1844, in Lyon, France; died March 12, 1937, in Paris) Symphony for Organ and Orchestra (No. 6), Opus 42 bis I. Allegro maestoso When Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), theologian, organist, physician, and humanitarian, was detained as an enemy alien at Saint-Rémy during the First World War, he was left for a considerable period without access to a keyboard, unable to play the music that might have helped sustain him through that difficult time. Schweitzer tells us how he survived: He spent hours memorizing music in his head, “playing” one extremely difficult work in particular over and over, so that once he was released he might be able to execute it flawlessly. The work: Organ Symphony No. 6 in G minor by his teacher, Charles-Marie Widor. This poignant snapshot offers a brief glimpse into the deep, multi-layered friendship between these two men. Widor, the elder by about thirty years, was for many years Schweitzer’s teacher. Yet Widor himself tells us how often master wound up as student; how regularly and how naturally these roles were reversed as two kindred spirits found each other in their shared love and reverence for Bach, for balance, for beauty, and, most of all, for the organ. -

JONGEN: Danse Lente for Flute and Harp Notes on the Program by Noel Morris ©2021

JONGEN: Danse lente for Flute and Harp Notes on the Program By Noel Morris ©2021 en years ago, a video of a Jongen’s Sinfonia is a masterpiece, a tour de crowded department store force celebrated by organists around the at Christmastime went world. Unfortunately, due to a series of Tviral. In it, holiday shoppers mishaps, the Sinfonia waited more suddenly find themselves than 80 years for a performance on awash in music—a thundering the Wanamaker Organ. rendition of the Hallelujah Chorus. The video shows Today, Jongen is best bewildered customers, remembered as an organ store clerks and live singers composer, although he wrote shuffling about in a chamber works, a symphony gleeful heap. It happened and concertos, among other at a Philadelphia Macy’s things. It’s only been in recent (formerly Wanamaker’s), years that musicians have begun home of the world’s largest to explore Jongen’s other works. pipe organ. From an early age, Jongen The Wanamaker Organ was the excelled at the piano and began to crown jewel of one of America’s dabble in composition; he entered first department stores. During the the Liège Conservatory at age seven 1920s, Rodman Wanamaker paid to and continued his studies into his twenties. have the instrument refurbished and enlarged During the 1890s he worked as a church organist to 28,482 pipes and decided to commission some around Liège and later joined the faculty at the new music for its rededication. He chose the famous Conservatory. After the German army invaded Belgium Belgian organist Joseph Jongen, who responded in 1914, he took his family to England where he formed with his Sinfonia concertante (1926), a piece the a piano quartet and traveled the UK, entertaining a composer would later refer to as “that unfortunate war weary people. -

The Wanamaker Organ

MUSIC FOR ORGAN AND ORCHESTRA CTHeEn W AnN AiMaA k CERo OnRcGerA N PETER RICHARD CONTE, ORGAN SyMPHONy IN C • ROSSEN MIlANOv, CONDUCTOR tracklist Symphony No. 2 in A Major, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 91 Félix Alexandre Guilmant 1|I. Introduction et Allegro risoluto 10:18 2|II. Adagio con affetto 5:56 3|III. Scherzo (Vivace) 6:49 4|IV. Andante Sostenuto 2:39 5|V. Intermède et Allegro Con Brio 5:55 6 Alleluja, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 112 Joseph Jongen 5:58 7 Hymne, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 78 Jongen 8:52 Symphony No. 6 in G Minor, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 42b Charles-Marie Widor 8|I. Allegro Maestoso 9:21 9|II. Andante Cantabile 10:39 10 | III. Finale 6:47 TOTAL TIME : 73:16 2 3 the music FÉLIX ALEXANDRE GUILMANT Symphony No. 2 in A Major for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 91 Alexandre Guilmant (1837-1911), the renowned Parisian organist, teacher and composer, wrote this five- movement symphony in 1906. Two years before its composition, Guilmant played an acclaimed series of 40 recitals on the St. Louis World ’s Fair Organ —the largest organ in the world —before it became the nucleus of the present Wanamaker Organ. In the Symphony ’s first movement, Introduction et Allegro risoluto , a sprightly theme on the strings is offset by a deeper motif. That paves the way for the titanic entrance of full organ, with fugato expositions and moments of unbridled sensuousness, CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR building to a restless climax. An Adagio con affetto follows Symphony No 6 in G Minor in A-B-A form, building on the plaintive organ with silken for Organ and Orchestra, Op. -

Composers for the Pipe Organ from the Renaissance to the 20Th Century

Principal Composers for the Pipe Organ from the Renaissance to the 20th Century Including brief biographical and technical information, with selected references and musical examples Compiled for POPs for KIDs, the Children‘s Pipe Organ Project of the Wichita Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, by Carrol Hassman, FAGO, ChM, Internal Links to Information In this Document Arnolt Schlick César Franck Andrea & Giovanni Gabrieli Johannes Brahms Girolamo Frescobaldi Josef Rheinberger Jean Titelouze Alexandre Guilmant Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck Charles-Marie Widor Dieterich Buxtehude Louis Vierne Johann Pachelbel Max Reger François Couperin Wilhelm Middelschulte Nicolas de Grigny Marcel Dupré George Fredrick Händel Paul Hindemith Johann Sebastian Bach Jean Langlais Louis-Nicolas Clérambault Jehan Alain John Stanley Olivier Messiaen Haydn, Mozart, & Beethoven Links to information on other 20th century composers for the organ Felix Mendelssohn Young performer links Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel Pipe Organ reference sites Camille Saint-Saëns Credits for Facts and Performances Cited Almost all details in the articles below were gleaned from Wikipedia (and some of their own listed sources). All but a very few of the musical and video examples are drawn from postings on YouTube. The section of J.S. Bach also owes credit to Corliss Arnold’s Organ Literature: a Comprehensive Survey, 3rd ed.1 However, the Italicized interpolations, and many of the texts, are my own. Feedback will be appreciated. — Carrol Hassman, FAGO, ChM, Wichita Chapter AGO Earliest History of the Organ as an Instrument See the Wikipedia article on the Pipe Organ in Antiquity: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pipe_Organ#Antiquity Earliest Notated Keyboard Music, Late Medieval Period Like early music for the lute, the earliest organ music is notated in Tablature, not in the musical staff notation we know today. -

Caecilia V61n04 1935

Founded A.D. 1814 by John Singenberger JOSQUIN DESPRES (1450~1521) Vol. 61 APRIL - 1935 Entered as second class mat... ter, October 20. 1931, at the Post Office at Boston. Mass., under the Act of March 3. 1879. Formerly published in St. Francis, Wisconsin. Now issued Monthly Magazine of Catholic Church ,. and School Music monthly. except in July. Subscription: $3 per year, pay... Vol. 61 April, 1935 No.4 able in advance. Single copies SOc. IN THIS ISSUE HO'7orary Editor OTTO A. SINGENBERGER LITURGICAL SCHOOL FOR DIRECTORS 0]' CHOIRS ANNOUNCED 182 Managing Editor WILLIAM ARTHUR REILLY HYMNS Marie Schulte K'allenbach 183 Business and Editorial Office Do You LIKE LITURGICAL M USIC ~ 186 100 Boylston St., Boston, Mass. THE Boy OHOIR PROBLEM 187 Con tributors :<EV. LUDWIG BONVIN, S.J., NEW LITURGICAL CHOIR IN WISCONSIN Buffalo. N. Y. RAPIDLY PROGRESSING 189 DOM ADELARD BOUVILL... IERS. O.S.B.. Belmont. N. C. MUSIC AT THE INTERNATIONAL EUCHARISTIC V. REV. GREGORY HUGLE. CONGRESS IN BUENOS AIRES 190 O.S.B.. Conception. Mo. RT. REV. MSGR. LEO P. CURRENT COMMENTS: 191 MANZETTI, Roland Park. John Singenberger's Mass of St. Greg Md. REV. F. T. \VALTER. ory to be Sung by Chorus of Five Hun St. Francis. Wise. dred Voices. REV. JOSEPH VILLANI. S. C., Dr. Noble Praises Mauro-Cottone Mu San Francisco. Cal. REV. P. H. SCHAEFERS. SIC. Cleveland. Ohio. HARVARD PROFESSOR TRACES CHURCH MUSIC REV. H. GRUENDER, S.J., St. Louis. Mo. THROUGH THE AGES 191 SR. M. CHERUBIM. O.S.F. ADDRESS By REV. J OI-IN GLENNON, D.D. -

SEPTEMBER 2020 First United Methodist Church Lubbock, Texas (Rendering) a New Chapter Begins for Orgues Létourneau Cover Featur

THE DIAPASON SEPTEMBER 2020 First United Methodist Church Lubbock, Texas (rendering) A new chapter begins for Orgues Létourneau Cover feature on pages 18–19 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD MARTIN JEAN BÁLINT KAROSI JEAN-WILLY KUNZ HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE ROBERT MCCORMICK JACK MITCHENER BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAÚL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN JOSHUA STAFFORD CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO W͘K͘ŽdžϰϯϮ ĞĂƌďŽƌŶ,ĞŝŐŚƚƐ͕D/ϰဒϭϮϳ ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ĞŵĂŝůΛĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ဒϲϬͲϱϲϬͲϳဒϬϬ ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚ WŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH SEBASTIAN HEINDL INSPIRATIONS ENSEMBLE ϮϬϭဓ>ÊĦóÊÊ'ÙÄÝ /ÄãÙÄã®ÊĽKÙ¦Ä ÊÃÖã®ã®ÊÄt®ÄÄÙ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Eleventh Year: No. 9, Thank you, thank you, thank you Whole No. 1330 We are grateful for your continued support that keeps The SEPTEMBER 2020 Diapason moving forward, especially in the last six months. Established in 1909 To our readers who have renewed subscriptions and to our Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 advertisers who have continued advertising, thank you. 847/954-7989; [email protected] We are especially thankful for our cover feature spon- www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, sors during this tumultuous time. Several have needed to the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music reschedule or adapt. Some sponsors have been incredibly flexible in moving their sponsorships to accommodate the In this issue CONTENTS needs of others. Michael McNeil has provided an introduction to the For those wishing to reserve a cover feature in 2021, please FEATURES meantone tuning of Dom Bédos and Pierre Anton as found “The world’s most famous bell foundry” contact Jerome Butera, advertising director (jbutera@sgcmail. -

Felix-Alexandre Guilmant

OHS members may join as many chapters as they desire. Several chapters publish excellent newsletters with significant scholarly con- tent. Chapter and Newsletter, Membership Founding Date Editor, Address (•Datejoin�d OHS) andAnnual Membership Boston Organ Club Newsletter,E. A. Alan Laufman 1965,1976• Boadway, $5 Bo11. 104, Harrirville, NH 03460 Central New York, The Coupler, $5 Culver Mowers 1976 2371 Slaterville Rd., Bo11. 130, Brookt.onclale, NY The Organ Historical Society 14817 Box26811, Richmond, Virginia23261 Chicago Midwest, TheStopt Diapason, Julie Stephens 1980 SueanR.Friesen, $12 620 W. 47th St., Western (804)353-9226 Springe, IL 60668 OHS 0r,an Archive at Westminster Choir Collete, EasternIowa, 1982 Newsletter, AugustKnoll Princeton, New Jersey Mark Nemmers, $7 .5 0 Boir.486 Wheatland, IA 62777 TheNational Council GreaterNew York TheKeraulophon, Alan Laufman (as Officers and Councillors (all terms expire 1989) City, 1969 John Ogasapian,$5 above) William C.Aylesworth ............................... President Greater St . .uiuis, The Cypher, Eliza- John D. Phillippe 3230Harriaon, Evanst.on, IL60201 1975 beth Schmitt, $5 4336 DuPage Dr. Kristin Gronning Farmer ........................ Vice President Bridget.on, MO 63044 3060 Fraternity ChurchRd., Winet.on-Salem, NC 27107 Hilbus (Washington- Where the Tracker Peter Ziegler Michael D. Friesen .................................. Secretary Baltimore), 1970 Action Is, Carolyn 14300 Medwlck CL 2139 Haaeell Rd., Hoffman Eatate1, IL60196 Upper Marlboro, MD Fix, $4 20772 David M. Barnett ...................................TreaBUrer 423 N. Stafford Ave., Richmond, VA 23220 Mid-Hudson(New The Whistlebox, June Marvel Crown Hill Rd. James J.Hammann .........Councillor for Finance & Development York), 1978 Robert Guenther, $5 1787 Univenlity, Lincoln Park, MI 48146 Wapplngen Fall■, NY 12690 Timothy E. Smith .............