Chapter Five the Method to Get Enlightenment in the A^Tasahasrika- Prajnaparamita -Sutra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Guenther's Saraha: a Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON

J ournal of the international Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 17 • Number 1 • Summer 1994 HUGH B. URBAN and PAUL J. GRIFFITHS What Else Remains in Sunyata? An Investigation of Terms for Mental Imagery in the Madhyantavibhaga-Corpus 1 BROOK ZIPORYN Anti-Chan Polemics in Post Tang Tiantai 26 DING-HWA EVELYN HSIEH Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in's (1063-1135) Teaching of Ch'an Kung-an Practice: A Transition from the Literary Study of Ch'an Kung-an to the Practical JCan-hua Ch'an 66 ALLAN A. ANDREWS Honen and Popular Pure Land Piety: Assimilation and Transformation 96 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity Herbert Guenther. Ecstatic Spontaneity: Saraha's Three Cycles of Doha. Nanzan Studies in Asian Religions 4. Berkeley: Asian Humani ties Press, 1993. xvi + 241 pages. Saraha and His Scholars Saraha is one of the great figures in the history of Indian Mahayana Buddhism. As one of the earliest and certainly the most important of the eighty-four eccentric yogis known as the "great adepts" (mahasiddhas), he is as seminal and radical a figure in the tantric tradition as Nagarjuna is in the tradition of sutra-based Mahayana philosophy.l His corpus of what might (with a nod to Blake) be called "songs of experience," in such forms as the doha, caryagiti and vajragiti, profoundly influenced generations of Indian, and then Tibetan, tantric practitioners and poets, above all those who concerned themselves with experience of Maha- mudra, the "Great Seal," or "Great Symbol," about which Saraha wrote so much. -

Finnigan Karma Moral Responsibility Buddhist Ethics

Forthcoming in Vargas & Doris (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Moral Psychology 1 Karma, Moral Responsibility, and Buddhist Ethics Bronwyn Finnigan ANU The Buddha taught that there is no self. He also accepted a version of the doctrine of karmic rebirth, according to which good and bad actions accrue merit and demerit respectively and where this determines the nature of the agent’s next life and explains some of the beneficial or harmful occurrences in that life. But how is karmic rebirth possible if there are no selves? If there are no selves, it would seem there are no agents that could be held morally responsible for ‘their’ actions. If actions are those happenings in the world performed by agents, it would seem there are no actions. And if there are no agents and no actions, then morality and the notion of karmic retribution would seem to lose application. Historical opponents argued that the Buddha's teaching of no self was tantamount to moral nihilism. The Buddha, and later Buddhist philosophers, firmly reject this charge. The relevant philosophical issues span a vast intellectual terrain and inspired centuries of philosophical reflection and debate. This article will contextualise and survey some of the historical and contemporary debates relevant to moral psychology and Buddhist ethics. They include whether the Buddha's teaching of no-self is consistent with the possibility of moral responsibility; the role of retributivism in Buddhist thought; the possibility of a Buddhist account of free will; the scope and viability of recent attempts to naturalise karma to character virtues and vices, and whether and how right action is to be understood within a Buddhist framework. -

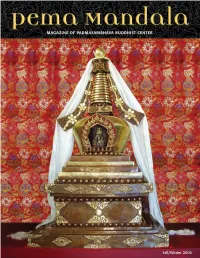

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

The Story of the Buddha and the Roots of Buddhism

The Story of The Buddha and the Roots of Buddhism Born in Nepal in the 6th (500’s) century B.C., Buddha was a spiritual leader and teacher whose life serves as the foundation of the Buddhist religion. A man named Siddhartha Gautama and he had achieved full awareness -- would one day become known as Buddha. thereby becoming Buddha. Buddha means "enlightened one" or "the awakened.” Siddhartha lived in Nepal during Early Years of His Life the 6th to 4th century B.C. While scholars The Buddha, or "enlightened one," was agree that he did in fact live, the events of his born Siddhartha (which means "he who life are still debated. According to the most achieves his aim") Gautama to a large clan widely known story of his life, after called the Shakyas in Lumbini in modern day experimenting with different teachings for Nepal in the 500’s B.C. His father was king years, and finding none of them acceptable, who ruled the tribe, known to be economically Gautama spent a fateful night in deep poor and on the outskirts geographically. His meditation. During his meditation, all of the mother died seven days after giving birth to answers he had been seeking became clear him, but a holy man prophesized great things explained that the ascetic had renounced the for the young Siddhartha: He would either be world to seek release from the human fear of a great king or military leader or he would be death and suffering. Siddhartha was a great spiritual leader. overcome by these sights, and the next day, To keep his son from witnessing the at age 29, he left his kingdom, wife and son miseries and suffering of the world, to lead an ascetic life, and determine a way Siddhartha's father raised him in extreme to relieve the universal suffering that he now luxury in a palace built just for the boy and understood to be one of the defining traits of sheltered him from knowledge of religion and humanity. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Spring 2015 Masterpieces and Iconic Artworks of the Asian Art Museum Sponsored by the Society for Asian Art

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Spring 2015 Masterpieces and Iconic Artworks of the Asian Art Museum Sponsored by The Society for Asian Art “The Buddha Triumphing Over Mara: Form and Meaning in Buddhist Art” Susan L. Huntington The Ohio State University 2.13.15 Goal of Lecture To explore a single masterpiece in the Asian Art Museum Collection from numerous perspectives, incluDing the historical anD religious purpose of the work, its importance as a representative of the Pala School of InDian sculpture, anD the materials anD techniques involved in its creation. Vocabulary and Terms Pala Dynasty (8th-12th century, eastern India and Bangladesh) Sakyamuni Buddha (historical Buddha of our era) Mara (“Death,” the enemy of the BuDDha) Mara Vijaya (Buddha’s victory over Mara) Bodh Gaya (Site in eastern India where Mara Vijaya occurred) Bodhi tree (Location at Bodh Gaya where Mara Vijaya occurred) Buddhism (the moral, ethical system that is the BuDDha’s legacy) Samsara (the world of illusion in which we dwell) Karma (our actions, gooD or baD, as Determinants of our progress) Nirvana (the ultimate goal of BuDDhism; to escape samsara) Four Noble Truths (the principles underpinning Buddhist teachings) Eightfold Path (the methoD by which we can escape samsara anD attain nirvana) Suggested Reading Casey, Jane Anne. Medieval Sculpture from Eastern India: Selections From the Nalin Collection. (New Jersey: Nalini International, 1985). See especially the appenDices regarDing the materials out of which the Pala-period works are maDe. Huntington, Susan L., with contributions by John C. Huntington. Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. (Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1985; reprint, New Delhi: Motilal BanarsiDass, 2014). -

A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation 2Nd

A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation An Explanation of Essential Topics for Dharma Students By Khenpo Gyaltsen Translated by Lhasey Lotsawa Translations ❁ A Lamp Illuminating the Path to Liberation An Explanation of Essential Topics for Dharma Students By Khenpo Gyaltsen ❁ Contents Foreword i 1. The Reasons for Practicing Buddhadharma 1 2. The Benefits of Practicing the Buddhadharma 4 3. The Way the Teacher Expounds the Dharma 7 4. The Way the Student Listens to the Dharma 10 5. Faith ~ the Root of All Dharma 16 6. Refuge ~ the Gateway to the Doctrine 20 7. Compassion ~ the Essence of the Path 34 8. The Four Seals ~ the Hallmark of the 39 Buddhadharma and the Essence of the Path 9. A Brief Explanation of Cause & Effect 54 10. The Ethics of the Ten Virtues and Ten Non-virtues 58 11. The Difference Between the One-day Vow and the 62 Fasting Vow 12. The Benefits of Constructing the Three 68 Representations of Enlightened Body, Speech, and Mind 13. How to Make Mandala Offerings to Gather the 74 Accumulations, and their Benefits 14. How to Make Water Offerings, and their Benefits 86 15. Butter Lamp Offerings and their Benefits 93 16. The Benefits of Offering Things such as Parasols 98 and Flowers 17. The Method of Prostrating and its Benefits 106 18. How to Make Circumambulations and their 114 Benefits 19. The Dharani Mantra of Buddha Shakyamuni: How 121 to Visualize and its Benefits 20. The Stages of Visualization of the Mani Mantra, 127 and its Benefits 21. The Significance of the Mani Wheel 133 22. -

Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations 1

Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations 1 Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations Chair • Whitney Cox Professors • Muzaffar Alam - Director of Graduate Studies • Dipesh Chakrabarty • Ulrike Stark • Gary Tubb Associate Professors • Whitney Cox • Thibaut d’Hubert • Sascha Ebeling • Rochona Majumdar Assistant Professors • Andrew Ollett • Tyler Williams - Director of Undergraduate Studies Visiting Professors • E. Annamalai Associated Faculty • Daniel A. Arnold (Divinity School) • Christian K. Wedemeyer (Divinity School) Instructional Professors • Mandira Bhaduri • Jason Grunebaum • Sujata Mahajan • Timsal Masud • Karma T. Ngodup Emeritus Faculty • Wendy Doniger • Ronald B. Inden • Colin P. Masica • C. M. Naim • Clinton B.Seely • Norman H. Zide The Department The Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations is a multidisciplinary department comprised of faculty with expertise in the languages, literatures, histories, philosophies, and religions of South Asia. The examination of South Asian texts, broadly defined, is the guiding principle of our Ph.D. degree, and the dissertation itself. This involves acquaintance with a wide range of South Asian texts and their historical contexts, and theoretical reflection on the conditions of understanding and interpreting these texts. These goals are met through departmental seminars and advanced language courses, which lead up to the dissertation project. The Department admits applications only for the Ph.D. degree, although graduate students in the doctoral program may receive an M.A. degree in the course of their work toward the Ph.D. Students admitted to the doctoral program are awarded a six-year fellowship package that includes full tuition, academic year stipends, stipends for some summers, and medical insurance. Experience in teaching positions is a required part of the 2 Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations program, and students are given opportunities to teach at several levels in both language courses and other courses. -

The Defeat of Mara

THE DEFEAT OF MARA The story of the Buddha, whose name means "the Enlightened One," is part history and part myth. The real Gautama Siddhartha was born in the 6th century B. C., a prince in the Shakya Kingdom of Northern India (now Nepal). Because he became a very great teacher of religious wisdom, his life story was reinterpreted in symbolic terms emphasizing his extraordinary nature. Before he was born, his mother dreamed of a radiant white elephant descending from heaven and entering her right side. Because of this dream, the positions of the stars at the time of his birth, and the unusual marks on his body, the holy men at the palace foretold that this child would grow up to be a great leader of men. He would be either a powerful and influential king or a wise religious teacher. His father, a king himself and member of the warrior caste, wanted his son, of course, to be a king. Therefore, from the time he was old enough to learn, Siddhartha's father The Buddha being born painlessly from his gave him everything he needed to become a great king. He was given mother’s side. lessons in history and government and was trained in all the arts of warfare. When the proper time came, the king arranged a marriage for Siddhartha with the most beautiful and gentle princess in the land. The prince enjoyed his life in the palace, loved his wife, and for many years never questioned his father's rule, which forbade him to go outside the city walls. -

Satan and Mara: Christian and Buddhist Symbols of Evil*

MDdern Ceylon Studies. volume 4: 1 '" .2. January '" July. 1973 Satan and Mara: Christian and Buddhist Symbols of Evil* JAMES W. BOYD Tho nature and meaning of what the early Christians and Buddhists experienced and defined as "evil" constitutes an important aspect of their religious experience. As counter to what they experienced as ultimately good and true, the experience of evil offers an alternate perspective from which to view and better to understand the meaning of the Christian "salvation in Christ" or the Buddhist "realizatcn of the Dharma" as taught by the Buddha. Recent studies in the symbolism of cvil.i and more specifically, an analysis of the symbols of Saran and Mara,? have not only demons- trated the intrinsic merit of such considerations but have also revealed the need for further scholarship in this arca.2 This study of the early Christian and Buddhist symbols of evil, Satan and Mara, is based on an examination of selected literature that falls within the formative period of each tradition (ca. 100 B.C.-ca. 350A.D.). In this early period the canonical litera- ture of Christians and Therav.idn Buddhists as well as important sutras of Mahayana Buddhists were written. Given the great diversity and amount ofliterature that falls wirhin this period, a selection of texts was made based on the following criteria: (1) the text must have material relevant to the topic, (2) the texts selected should be representariveof'earllcr and la ter literature and should i cf'ect different types of writings, and (3)the texts should provide a suitable basis of comparison with the other religious rradition.! Analysis of the texts proceeded as follows. -

Reiko Ohnuma Animal Doubles of the Buddha

H U M a N I M A L I A 7:2 Reiko Ohnuma Animal Doubles of the Buddh a The life-story of the Buddha, as related in traditional Buddha-biographies from India, has served as a masterful founding narrative for the religion as a whole, and an inexhaustible mine of images and concepts that have had deep reverberations throughout the Buddhist tradition. The basic story is well-known: The Buddha — who should properly be referred to as a bodhisattva (or “awakening-being”) until the moment when he attains awakening and becomes a buddha — is born into the world as a human prince named Prince Siddhārtha. He spends his youth in wealth, luxury, and ignorance, surrounded by hedonistic pleasures, and marries a beautiful princess named Yaśodharā, with whom he has a son. It is only at the age of twenty-nine that Prince Siddhārtha, through a series of dramatic events, comes to realize that all sentient beings are inevitably afflicted by old age, disease, death, and the perpetual suffering of samsara, the endless cycle of death-and-rebirth that characterizes the Buddhist universe. In response to this profound realization, he renounces his worldly life as a pampered prince and “goes forth from home into homelessness” (as the common Buddhist phrase describes it) to become a wandering ascetic. Six years later, while meditating under a fig tree (later known as the Bodhi Tree or Tree of Awakening), he succeeds in discovering a path to the elimination of all suffering — the ultimate Buddhist goal of nirvana — and thereby becomes the Buddha (the “Awakened One”).