Supplement Sheffield Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Application Form

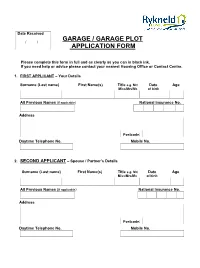

Date Received / / GARAGE / GARAGE PLOT APPLICATION FORM Please complete this form in full and as clearly as you can in black ink. If you need help or advice please contact your nearest Housing Office or Contact Centre. 1. FIRST APPLICANT – Your Details Surname (Last name) First Name(s) Title e.g. Mr/ Date Age Miss/Mrs/Ms of birth All Previous Names (If applicable) National Insurance No. Address Postcode: Daytime Telephone No. Mobile No. 2. SECOND APPLICANT – Spouse / Partner’s Details Surname (Last name) First Name(s) Title e.g. Mr/ Date Age Miss/Mrs/Ms of birth All Previous Names (If applicable) National Insurance No. Address Postcode: Daytime Telephone No. Mobile No. 3. At Your Present Address Are you? Is your joint applicant? Council Tenant Owner Occupier Lodger Tied Tenant Housing Association Private Landlord 4. Do you currently rent or have you ever rented a garage Yes: No: from North East Derbyshire District Council 5. Do you currently rent or have you ever rented a garage plot Yes: No: from North East Derbyshire District Council If you answered No to questions 5 or 6, please go to Question 8 6. Where is/was the site situated? 7. If you are applying for an additional Garage / Garage Plot please state reason(s) why? 8. Do you require a Garage? Yes: No: 9. Do you require a Garage Plot? Yes: No: Eligibility to Register • Have you committed a criminal offence or engaged in criminal or anti social activity? Yes No If Yes please supply details: • Do you owe this council or any other landlord current rent arrears, former tenant’s arrears or any sundry debts? Yes No If Yes please supply details: • Are you, or have you been in the past, subject to any formal notice to seek possession of your home? Yes No If Yes please supply details: I / we* certify that the whole of the particulars given in this Application for a Garage/Garage Plot are true. -

Radiocarbon, Vol

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 5, 1963, P. 1-221 Radiocarbon 1963 UCLA RADIOCARBON DATE'S II G. J. FERGUSSON and W. F. LIBBY Institute of Geophysics, University of California, Los Angeles 24, California The measurements reported in this list have been made in the Isotope Laboratory at the Institute of Geophysics, UCLA during 1962. Dates have been calculated on the C14 half life of 5568 years and using 95% NBS oxalic acid as modern standard, in agreement with the decision of the Fifth Radiocarbon Dating Conference (Godwin, 1962). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to the National Science Foundation for Grant G-14287 for financial support for this work, and also acknowledge the excellent assist- ance of Ervin Taylor and Carleton Hoel with laboratory work. SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS A. United States UCLA-131. Ash Cave, Washington 7940 ± 150 5990 B.C. Charcoal and charred midden material from hearth at Ash Cave (45WW61) in the lower Snake River canyon, Walla Walla County, Washington (46° 33' N Lat, 118° 33' W Long). Hearth was located at surface of a deep midden deposit (Stratum 3) mantled by a layer of Mt. Mazama ash (Stratum 2). Enclosed in the midden deposit were remains typical of the Old Cordilleran culture in the Pacific Northwest (Butler, 1961). Coll. 1958 by B. R. Butler; subm. by E. H. Swanson Jr., Idaho State College Mus. Comment (B.R.B.) : Mt. Mazama ash separates Old Cordilleran culture components from the subsequent Cold Springs horizon at various sites in the Columbia Plateau; the Ash Cave date provides a terminus ante quern date for this geologic horizon marker and for the Cold Springs horizon in the Columbia Plateau. -

“The Tree Which Moves Some to Tears of Joy Is in the Eyes of Others Only a Green Thing That Stands in the Way. Some See Nature All Ridicule and Deformity

DORE VILLAGE SOCIETY NO. 126 SUMMER 2017 ISSN 0965-8912 “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity... and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.” - William Blake DORE VILLAGE SOCIETY Transitional arrangements shall apply, as minuted by the Executive Committee and to ensure the smooth running of the Society, for ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING the early years of the introduction of this policy with effect from the Notice is hereby given that the 52nd Annual General Meeting of Annual General Meeting in 2017. the Dore Village Society will be held at Dore Methodist Church, A second change to the Constitution is also recommended. High Street, Dore at 7.30pm on Wednesday 7th June 2017. Section 14 of the constitution refers to the ways in which notices are deemed to have been given to members. At the moment the current AGENDA wording in section 14 of the constitution reads as follows: “Any notices required to be given by this constitution shall be deemed 1. Apologies. to be duly given if published in Dore to Door, displayed on the 2. Approval of the minutes of the 51st Annual General Meeting. Society’s notice board or left at or sent by prepaid post to members 3. Trustees’ statement. using the address last notified to the Secretary”.It is recommended 4. To approve the accounts for the year ended 31st December that the word “Secretary” is replaced with “Membership Secretary” 2016. -

SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS of DERBYSHIRE, and THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 Changes Were Made to This Account by Linda Moffatt on 19 February 2019

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire & their descendants 1600-1915 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS OF DERBYSHIRE, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 Changes were made to this account by Linda Moffatt on 19 February 2019. by Linda Moffatt Parrsboro families have been transferred to Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, 2nd edition by Linda Moffatt© March 2016 Bath and Frome, Somerset, from 1440. 1st edition by Linda Moffatt© 2015 This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and omissions, alternative interpretations of the early families, additional information for consideration for future updates. She can be contacted at [email protected] DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

'SHEFFIELD.·Gttjs5ary

. ,- .... Enolfsb J>lalect Socfetp. 'SerIes C.-ORIGINAL GLOS-SARiES. No. 62. r r i ~ ~ - i '. I l' ~ ~ I ( • " ...... .> :"-;.. - 'SHEFFIELD .·GttJS5ARY :i I , . '- BY ..., \ SIDNEY OLDALLr;ADDY·.. , M.A. " Son~n: PUBLISHED FOR iTHE ENGUSH DIALECT SOCIBTY. BY KEGAN PAl'L, TRENCH. Ta\i9NER a' co. ' • - ISgI Prill 'iw S"", ." • . ~ .. (gommittee: Priuce LoUIS LUCIBN BoNAPARTE. Dr. J. A. H. MURRAY, Oxford. JAMBS BRlnBN, P.L.S. J. H. NODAL, Heaton Moor. Rev. J. W. CARTMELL, M.A., Cambridge W ILLIAM PAYNE, London. Col. H. FISRWICK. F.S.A., Rochdale. Rev. Prof. SKEAT, M.A., Cambridge. JOSEPH HALL, M.A., M~chester. JOSEPH THOMPSON, Manchester. THOMAS HALLAM, Mp.nchester. T. NORTHCOTE TOLLER, M.A. ROBBRT HOLLAND, Frodsham. Professor A. S. WILKINS, M.A. GBORGE MILNER, AltriDcham. BANKERS: MANCHESTER & COU~TY BANK, King Street, Manchester. • 0"" .. .. t· .- . The Subscription is One Pound per annum, which shoulJ be paid to the Treasurer, GEORGE MILNER, Esq., The MaDor House, Altrincham, Cheshire. either by cheque or post-office order (made payable at the Manchester Post Office); or to the _account of. t~ Socie~y~s ~aDkers, the MANCHESTER AND COUNTY BANK, King Street, Manchester. The subscriptions are due, in.- advance, on the first of January. ,~. All other communications should be addressed to > • J.. H. NODAL,- 1I0~OlU~Y ~Be~ARY~ - The Gvange. Heallm Mf1fW. flf(W S~~. , g • . II. •• .. ," A" ., .. \i,;. :1 ..' ~:''''''' SHEFFIELD GLOSSARY SUPPLEMENT. • A SUPPLEMENT TO THE SHEFFIELD GLOSSARY BY SIDNEY OLD~\LI.J l\DI)Y, ~I.I\. 1on~on: PVBLISHED Fan TilE E:\GLISII DIALECT SOCIETY BY I'EGAS 1'.\t'l. -

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE Final Recommendations for Ward Bo

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of North East Derbyshire August 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. K KILLAMARSH EAST RIDGEWAY & MARSH LANE KILLAMARSH CP KILLAMARSH WEST F I B E ECKINGTON NORTH A COAL ASTON ECKINGTON CP DRONFIELD WOODHOUSE H C DRONFIELD CP DRONFIELD NORTH J GOSFORTH VALLEY L ECKINGTON SOUTH & RENISHAW G D DRONFIELD SOUTH UNSTONE UNSTONE CP HOLMESFIELD CP BARLOW & HOLMESFIELD KEY TO PARISH WARDS BARLOW CP DRONFIELD CP A BOWSHAW B COAL ASTON C DRONFIELD NORTH D DRONFIELD SOUTH E DRONFIELD WOODHOUSE F DYCHE G GOSFORTH VALLEY H SUMMERFIELD ECKINGTON CP I ECKINGTON NORTH J ECKINGTON SOUTH K MARSH LANE, RIDGEWAY & TROWAY L RENISHAW & SPINKHILL NORTH WINGFIELD CP M CENTRAL BRAMPTON CP N EAST O WEST WINGERWORTH CP P ADLINGTON Q HARDWICK WOOD BRAMPTON & WALTON R LONGEDGE S WINGERWORTH T WOODTHORPE CALOW CP SUTTON SUTTON CUM DUCKMANTON CP HOLYMOORSIDE AND WALTON CP GRASSMOOR GRASSMOOR, TEMPLE S HASLAND AND NORMANTON -

TRO Moss Road, Totley Moor, Holmesfield

DATED 6 DECEMBER 2001 THE DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 (MOSS ROAD, TOTLEY MOOR, HOLMESFIELD- BRIDLEWAY 60) (PROHIBITION OF DRIVING) ORDER 2001 1 I' i'I .. I t ) ! I' . DWTYSOE MATLOCK ;--' ' 1;u iWAii!iii Jt iM a THE DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 (MOSS ROAD, TOTLEY MOOR, HOLMESFIELD- BRIDLEWAY 60) (PROHIBITION OF DRIVING) ORDER 2001 THE DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL in exercise of its powers under Section 1 (1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 ("the Act") and of all other enabling powers, after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police, hereby make the following Order:- 1 No person shall cause any vehicle to proceed in the length of road specified in the Schedule to this Order. 2 This Order shall come into operation on the Seventeenth day of December 2001 and may be cited as the Derbyshire County Council (Moss Road, Totley Moor, Holmesfield - Bridleway 60) (Prohibition of Driving) Order 2001. SCHEDULE PROHIBITION OF DRIVING Length of Bridleway at Moss Road, Totley Moor, Holmesfield - Bridleway 60 ) From its Junction with Owler Bar Road in a generally Easterly direction to the County boundary, including any alternative routes established along or adjacent to the general line of the road. THE COMMON SEAL of the ) Derbyshire County Council ) was hereunto affixed the ) Sixth day of December Two ) thousand and One in the ) presence of:- ) The Director of Environmental Services detailed the implications for the work of the County Council. Overall , the Act introduced some welcome development, from the "right to roam" and changes in rights of way legislation to stronger protection for wildlife sites and species. -

East Midlands

East Midlands Initial proposals Contents Initial proposals summary .............................................................................. 3 1. What is the Boundary Commission for England? ........... 5 2. Background to the 2013 Review ...................................................... 6 3. Initial proposals for the East Midlands region ................... 9 Initial proposals for the Lincolnshire sub-region .................................................................. 9 Initial proposals for the Derbyshire sub-region ..................................................................... 10 Initial proposals for the Northamptonshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire sub-region ............................................................................................................................................ 11 4. How to have your say ................................................................................. 14 Annex: Initial proposals for constituencies, including wards and electorates ........................................................................................ 17 Glossary ............................................................................................................................ 33 Initial proposals summary Who we are and what we do of constituencies allocated to each sub- region is determined by the electorate of the The Boundary Commission for England is an combined local authorities. independent and impartial non-departmental public body which is responsible for reviewing -

Advertise with Us

Wingerworth,e community Ashover, magazine for Tupton & surrounding villages W www. Issue 76 - June/July 2010 i 5,000n free copies AActivective g 57777 g No 84 FebruaFebruaryry 20120100 115,505,5000 free distribution TeTel:l: 01140 114 23 2357777 8 s Inside: 8 Town Council The big breakfast Annual Report Pag es 12-14 dronfieldEY Tel 0114 2357777 Issue 57 July 2010 www.dronfieldeye.co.uk ummer’s wst Free to 15,000 homes throughout S18 and beyond magazine No 1 October 2010 ere at last www.heronpublications.co.uk Tel: 01246 380016 AA FeastFeast ofof ere at last T 15,000 free copies delivered to homes & businesses A splash of Hello FlowersFlowers Chesterfield! SpringSpring Meet the new Mayor Bear’s Dronfield boat The big breakfast Scarecrow Festival Food & Drink ideas • Holly’s golfingPedalling glory to Portugal Eye on gardens ue update • Norton POW campDave Berry memories event • Angling mystery solved l news • Holiday ideasSwapping designs My kind MEDIA PACK w st Tmagazine Wings www.active8magazine.co.uk as & Issue 51 ear 2009 Christm Y w AActivectivedronfieldNe May 2010 15,500 free distribution Tel: 0114 2357777 The community magazine for 815,000 copies delivered free throughout S www.dronfieldeye.co.uk Wingerworth, Ashover & surrounding villages T e & surrounding villages lep h o n e :0 18 & beyond nk your teeth 1 1 ink your teeth 4 2 3 5 7 7 nto this month’s 7 7 EYE s asty magazine: Wishing a Merry iinnggs f mancemance ChristmasWWIssue and 74 - February/March a 2010 5,000 copies Happy New Year o r g e rw W in Ashover, Tupton & ear 2009 -

St Swithins Church the Light on the Hill Our Mission Statement “You Are the Light of the World

Parish Profile for Team Vicar for St Swithin’s and St Philip’s in Dronfield with Holmesfield Team Ministry Welcome Thank you for taking the time to consider our ministerial vacancy. We are a team of five Anglican churches:- St John’s (Dronfield Parish Church), St Swithin’s (Holmesfield), St Andrew’s (Dronfield Woodhouse), St Philip’s (Holmesdale) and St Mary’s (Unstone). The ministers work together as a team, headed by our Rector Revd Peter Bold. Dronfield and Holmesfield are situated between Chesterfield and Sheffield, on the edge of the Peak District National Park. A wonderful place to live. The vacancy is for a team vicar, to be the vicar of St Swithin’s while also giving significant oversight to St Philip’s and playing an active part in the whole team. We are also active members of CTDD (Churches Together Dronfield & District), which encompasses 13 churches within a six mile radius, including Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Catholic, United Reform and Wesleyan Reform. We hope you enjoy reading about our team and our churches. For further information please see contact details on the last page. Our Current Clergy Team Currently our clergy team consists of: • A Team Rector, Peter Bold, who is responsible for St John’s and has given oversight to St Philip’s. • A Team vicar, Paul Mellars, who leads St Andrew’s and also gives oversight to St Mary’s. • A second year stipendiary curate, Joel Bird, who is leading St Philip’s. • A self supporting associate priest, based at St Andrew’s, and two retired priests. -

Dronfield Neighbourhood Plan V14c

DRONFIELD Neighbourhood Plan 2018 Draft Version 14c Dronfield Town Council ii Contents Dronfield: Neighbourhood Plan Table of Contents ■ WHAT IS A NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN? 5 TRANSPORT & ACCESS 25 4. PROTECTION OF IMPORTANT 41 COMMUNITY ASSETS HOW DOES A NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN THE PLAN AIMS 26 5 FIT INTO THE PLANNING SYSTEM? BACKGROUND 26 5. LISTED BUILDINGS 42 HOW IS THE PLAN STRUCTURED? 5 Traffic Management and Congestion 26 6. DRONFIELD CHARACTER BUILIDINGS ABOUT DRONFIELD 6 Sustainable Transport 27 AND STRUCTURES OF LOCAL HERITAGE INTEREST IDENTIFICATION CRITERIA HISTORY OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 7 Cycling and Walking 27 Appendix 6 can be viewed online at THE PLAN’S AIMS & OBJECTIVES 8 Car Parking 28 www.dronfield.gov.uk/neighbourhood-plan 7. PROPOSED DRONFIELD CHARACTER COMMUNITY ASSETS 9 ECONOMY 29 BUILIDINGS AND STRUCTURES OF LOCAL OBJECTIVES 10 THE PLAN AIMS 30 HERITAGE INTEREST. 44 BACKGROUND 10 BACKGROUND 30 8. PROPOSED GREEN SPACES Health 10 Town Centre 30 OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE 49 Education 10 Shop Frontages in the Town Centre 31 9. EVIDENCE BASE 51 Services 10 Litter in the Town 32 Assets of Community Value 12 Shopping Hubs 32 GLOSSARY 51 Hot Food Takeaways 33 MAPS NATURAL ENVIRONMENT 13 Businesses and Employment 33 MAP 1 GREEN BELT 52 THE PLAN AIMS 14 MAP 2 TRAFFIC ACCIDENT DATA 53 BACKGROUND 14 HERITAGE 35 MAP 3 PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK. 54 Green Belt 14 THE PLAN AIMS 35 MAP 4 TOWN CENTRE 55 Landscape Character 14 BACKGROUND 35 MAP 5 CONSERVATION AREAS 56 Green and Blue Infrastructure 16 Historic Buildings 35 MAP 6 LISTED BUILDINGS 57 Local Green Spaces 17 Dronfield Character Buildings and MAP 7 PROPOSED LOCAL GREEN SPACES & Structures of Local Heritage Interest 36 Trees and Woodlands 18 LEA BROOK VALLEY GREEN CORRIDOR 58 Conservation Areas 38 MAP 8 DRONFIELD NEIGHBOURHOOD HOUSING & INFRASTRUCTURE 19 Design 39 PLAN AREA 59 THE PLAN AIMS 20 BACKGROUND 20 APPENDICES 41 Housing Allocation 20 1. -

Initial Proposals for New Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries in the East Midlands Contents

Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the East Midlands Contents Summary 3 1 What is the Boundary Commission for England? 5 2 Background to the 2018 Review 7 3 Initial proposals for the East Midlands 11 Initial proposals for the Lincolnshire sub‑region 12 Initial proposals for the Derbyshire sub‑region 13 Initial proposals for the Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, 14 Rutland and Northamptonshire sub‑region 4 How to have your say 19 Annex A: Initial proposals for constituencies, 23 including wards and electorates Glossary 39 Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the East Midlands 1 Summary Who we are and what we do What is changing in the East Midlands? The Boundary Commission for England is an independent and impartial The East Midlands has been allocated 44 non‑departmental public body which is constituencies – a reduction of two from responsible for reviewing Parliamentary the current number. constituency boundaries in England. Our proposals leave seven of the 46 The 2018 Review existing constituencies unchanged. We have the task of periodically reviewing As it has not always been possible to the boundaries of all the Parliamentary allocate whole numbers of constituencies constituencies in England. We are currently to individual counties, we have grouped conducting a review on the basis of rules some county and local authority areas set by Parliament in 2011. The rules tell into sub‑regions. The number of us that we must make recommendations constituencies allocated to each sub‑region for new Parliamentary constituency is determined by the electorate of the boundaries in September 2018. They combined local authorities.