Obesogens in the Aquatic Environment an Evolutionary And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemicals in the Fourth Report and Updated Tables Pdf Icon[PDF

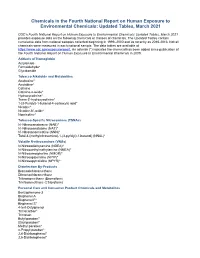

Chemicals in the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 CDC’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 provides exposure data on the following chemicals or classes of chemicals. The Updated Tables contain cumulative data from national samples collected beginning in 1999–2000 and as recently as 2015-2016. Not all chemicals were measured in each national sample. The data tables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. An asterisk (*) indicates the chemical has been added since publication of the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in 2009. Adducts of Hemoglobin Acrylamide Formaldehyde* Glycidamide Tobacco Alkaloids and Metabolites Anabasine* Anatabine* Cotinine Cotinine-n-oxide* Hydroxycotinine* Trans-3’-hydroxycotinine* 1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-butanol-4-carboxylic acid* Nicotine* Nicotine-N’-oxide* Nornicotine* Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) N’-Nitrosoanabasine (NAB)* N’-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT)* N’-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN)* Total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol) (NNAL)* Volatile N-nitrosamines (VNAs) N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)* N-Nitrosoethylmethylamine (NMEA)* N-Nitrosomorpholine (NMOR)* N-Nitrosopiperidine (NPIP)* N-Nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR)* Disinfection By-Products Bromodichloromethane Dibromochloromethane Tribromomethane (Bromoform) Trichloromethane (Chloroform) Personal Care and Consumer Product Chemicals and Metabolites Benzophenone-3 Bisphenol A Bisphenol F* Bisphenol -

DRAFT Indicators Biomonitoring: Perfluorochemicals (Pfcs)

America’s Children and the Environment, Third Edition DRAFT Indicators Biomonitoring: Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) EPA is preparing the third edition of America’s Children and the Environment (ACE3), following the previous editions published in December 2000 and February 2003. ACE is EPA’s compilation of children’s environmental health indicators and related information, drawing on the best national data sources available for characterizing important aspects of the relationship between environmental contaminants and children’s health. ACE includes four sections: Environments and Contaminants, Biomonitoring, Health, and Special Features. EPA has prepared draft indicator documents for ACE3 representing 23 children's environmental health topics and presenting a total of 42 proposed children's environmental health indicators. This document presents the draft text, indicator, and documentation for the PFCs topic in the Biomonitoring section. THIS INFORMATION IS DISTRIBUTED SOLELY FOR THE PURPOSE OF PRE- DISSEMINATION PEER REVIEW UNDER APPLICABLE INFORMATION QUALITY GUIDELINES. IT HAS NOT BEEN FORMALLY DISSEMINATED BY EPA. IT DOES NOT REPRESENT AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED TO REPRESENT ANY AGENCY DETERMINATION OR POLICY. For more information on America’s Children and the Environment, please visit www.epa.gov/ace. For instructions on how to submit comments on the draft ACE3 indicators, please visit www.epa.gov/ace/ace3drafts/. March 2011 DRAFT: DO NOT QUOTE OR CITE Biomonitoring: Perfluorochemicals 1 Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) 2 3 Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) are a group of manmade chemicals that have been used since the 4 1950s in many consumer products.1 The structure of these chemicals makes them very stable, 5 hydrophobic (water-repelling), and oleophobic (oil-repelling). -

And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances – Chemical Variation and Applicability of Current Fate Models

CSIRO PUBLISHING Environ. Chem. 2020, 17, 498–508 Research Paper https://doi.org/10.1071/EN19296 Investigating the OECD database of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances – chemical variation and applicability of current fate models Ioana C. Chelcea,A Lutz Ahrens,B Stefan O¨ rn,C Daniel MucsD and Patrik L. Andersson A,E ADepartment of Chemistry, Umea˚ University, SE-901 87 Umea˚, Sweden. BDepartment of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Box 7050, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden. CDepartment of Biomedical Sciences and Veterinary Public Health, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden. DRISE SP – Chemical and Pharmaceutical Safety, Forskargatan 20, 151 36 So¨derta¨lje, Sweden. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Environmental context. A diverse range of materials contain organofluorine chemicals, some of which are hazardous and widely distributed in the environment. We investigated an inventory of over 4700 organofluorine compounds, characterised their chemical diversity and selected representatives for future testing to fill knowledge gaps about their environmental fate and effects. Fate and property models were examined and concluded to be valid for only a fraction of studied organofluorines. Abstract. Many per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) have been identified in the environment, and some have been shown to be extremely persistent and even toxic, thus raising concerns about their effects on human health and the environment. Despite this, little is known about most PFASs. In this study, the comprehensive database of over 4700 PFAS entries recently compiled by the OECD was curated and the chemical variation was analysed in detail. -

The Obesogen Hypothesis: Current Status and Implications for Human Health

Curr Envir Health Rpt (2014) 1:333–340 DOI 10.1007/s40572-014-0026-8 MECHANISMS OF TOXICITY (CJ MATTINGLY, SECTION EDITOR) The Obesogen Hypothesis: Current Status and Implications for Human Health Jerrold J. Heindel & Thaddeus T. Schug Published online: 20 September 2014 # Springer International Publishing AG (outside the USA) 2014 Abstract Obesity and diabetes have overtaken smoking as agreed upon that this obesity epidemic is the product of poor the number 1 preventable health determinate in the United nutrition and lack of exercise. However, obesity is a complex States. In its basic form, obesity is due to disruptions of the endocrine disease caused by disruption of many control sys- endocrine systems that control food intake, satiety, and meta- tems involving interaction between genetic and environmental bolic rate. Recent studies have identified a subclass of endo- cues such as nutrition, exercise, drugs, behavior, alterations in crine disrupting chemicals that interfere with hormonally reg- the microbiome, and exposure to environmental chemicals. ulated metabolic processes, especially during early develop- Genome wide association studies using large populations ment. These chemicals, called “obesogens,” may predispose have uncovered some 40 novel single nucleotide polymor- individuals to gain weight despite efforts to limit caloric intake phisms that are associated with increased body mass index and increase physical activity. Evidence suggests that chemi- (BMI), but together these genetic identifiers account for less cal exposures early in life can predispose individuals to weight than 5 % of the incidence of obesity [2]. Indeed, there are no gain through programming changes, which may enhance dys- known genetic mechanisms that can explain the remarkable functional eating behaviors later in life. -

Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Serum Perfluorinated Alkyl Acid Concentrations and Dental Caries Among US Adolescents (NHANES 1999–2012)

Open access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024189 on 5 February 2019. Downloaded from Cross-sectional study of the association between serum perfluorinated alkyl acid concentrations and dental caries among US adolescents (NHANES 1999–2012) Nithya Puttige Ramesh,1 Manish Arora,2 Joseph M Braun1 To cite: Puttige Ramesh N, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Arora M, Braun JM. Cross- Study objectives Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are a class sectional study of the of anthropogenic and persistent compounds that may ► Our study contributes to a gap in the literature by association between serum impact some biological pathways related to oral health. perfluorinated alkyl acid examining the relationship between perfluoroalkyl The objective of our study was to estimate the relationship concentrations and dental caries acid exposure and dental caries prevalence among between dental caries prevalence and exposure to four among US adolescents (NHANES adolescents, which, to the best of our knowledge, PFAA: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorononanoic 1999–2012). BMJ Open has not been examined before. 2019;9:e024189. doi:10.1136/ acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) and ► The strengths of our study include the large sample perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) in a nationally bmjopen-2018-024189 size (2869 participants) and the nationally repre- representative sample of US adolescents. Prepublication history and sentative nature of the National Health and Nutrition ► Setting/Design We analysed cross-sectional data from additional material for this Examination Survey (NHANES). the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from paper are available online. To ► Although we adjusted for potential confounders, 1999 to 2012 for 12–19-year-old US adolescents. -

PFAS MCL Technical Support Document

ATTACHMENT 1 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) And Letter from Dr. Stephen M. Roberts, Ph.D. dated 6/25/2019 – Findings of Peer Review Conducted on Technical Background Report June 28, 2019 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) June 28, 2019 Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii Section I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 1 Section II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Section III. Reference Dose Derivation ........................................................................................................ -

Us 2018 / 0296525 A1

UN US 20180296525A1 ( 19) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication (10 ) Pub. No. : US 2018/ 0296525 A1 ROIZMAN et al. ( 43 ) Pub . Date: Oct. 18 , 2018 ( 54 ) TREATMENT OF AGE - RELATED MACULAR A61K 38 /1709 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 38 / 1866 DEGENERATION AND OTHER EYE (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 31/ 40 ( 2013 .01 ) DISEASES WITH ONE OR MORE THERAPEUTIC AGENTS (71 ) Applicant: MacRegen , Inc ., San Jose , CA (US ) (57 ) ABSTRACT ( 72 ) Inventors : Keith ROIZMAN , San Jose , CA (US ) ; The present disclosure provides therapeutic agents for the Martin RUDOLF , Luebeck (DE ) treatment of age - related macular degeneration ( AMD ) and other eye disorders. One or more therapeutic agents can be (21 ) Appl. No .: 15 /910 , 992 used to treat any stages ( including the early , intermediate ( 22 ) Filed : Mar. 2 , 2018 and advance stages ) of AMD , and any phenotypes of AMD , including geographic atrophy ( including non -central GA and Related U . S . Application Data central GA ) and neovascularization ( including types 1 , 2 and 3 NV ) . In certain embodiments , an anti - dyslipidemic agent ( 60 ) Provisional application No . 62/ 467 ,073 , filed on Mar . ( e . g . , an apolipoprotein mimetic and / or a statin ) is used 3 , 2017 . alone to treat or slow the progression of atrophic AMD Publication Classification ( including early AMD and intermediate AMD ) , and / or to (51 ) Int. CI. prevent or delay the onset of AMD , advanced AMD and /or A61K 31/ 366 ( 2006 . 01 ) neovascular AMD . In further embodiments , two or more A61P 27 /02 ( 2006 .01 ) therapeutic agents ( e . g ., any combinations of an anti - dys A61K 9 / 00 ( 2006 . 01 ) lipidemic agent, an antioxidant, an anti- inflammatory agent, A61K 31 / 40 ( 2006 .01 ) a complement inhibitor, a neuroprotector and an anti - angio A61K 45 / 06 ( 2006 .01 ) genic agent ) that target multiple underlying factors of AMD A61K 38 / 17 ( 2006 .01 ) ( e . -

Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)

United States Office of Water EPA 822-R-16-003 Environmental Protection Mail Code 4304T May 2016 Agency Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 i Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water (4304T) Health and Ecological Criteria Division Washington, DC 20460 EPA Document Number: 822-R-16-003 May 2016 Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 ii BACKGROUND The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), as amended in 1996, requires the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to periodically publish a list of unregulated chemical contaminants known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and that may require regulation under SDWA. The SDWA also requires the Agency to make regulatory determinations on at least five contaminants on the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) every 5 years. For each contaminant on the CCL, before EPA makes a regulatory determination, the Agency needs to obtain sufficient data to conduct analyses on the extent to which the contaminant occurs and the risk it poses to populations via drinking water. Ultimately, this information will assist the Agency in determining the most appropriate course of action in relation to the contaminant (e.g., developing a regulation to control it in drinking water, developing guidance, or deciding not to regulate it). The PFOA health assessment was initiated by the Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology in 2009. The draft Health Effects Support Document for Perfluoroctanoic Acid (PFOA) was completed in 2013 and released for public comment in February 2014. -

United Nations Sc

UNITED NATIONS SC UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/INF/16 Distr.: General 2 August 2016 English only Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee Twelfth meeting Rome, 19–23 September 2015 Item 4 (d) of the provisional agenda Technical work: consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Comments and responses relating to the draft consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Note by the Secretariat As referred to in the note by the Secretariat on guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals (UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/7), the annex to the present note contains a table listing the comments and responses relating to the draft guidance. The present note, including its annex, has not been formally edited. UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/1. 030816 UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/INF/16 Annex Comments and responses relating to the draft consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Minor grammatical or spelling changes have been made without acknowledgment. Only substantial comments are listed. Yellow highlight indicates addition of text while green highlight indicates deletion. Source of Page Para Comments on the second draft Response Comment Austria 7 2 This statement is better placed in Chapter VII Rejected. accompanied with a justification for those “critical applications”. For clarification “where it is not currently possible without the use of PFOS” is added Austria 15 47 According to May be commercialized is revised to http://poppub.bcrc.cn/col/1413428117937/index.html “are commercialized” F-53 and F-53B have a long history of usage and have been commercialized before PFOS related Reference substances were used (cf. -

Microbiota and Obesogens: Environmental Regulators of Fat Storage

Microbiota and obesogens: environmental regulators of fat storage John F. Rawls, Ph.D. Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology Center for Genomics of Microbial Systems Duke University School of Medicine Seminar outline 1. Introduction to the microbiota 2. Microbiota as environmental factors in obesity 3. Obesogens as environmental factors in obesity Seeing and understanding the unseen Antonie van Leewenhoek 1620’s: Described differences between microbes associated with teeth & feces during health & disease. Louis Pasteur 1850’s: Helps establish the “germ theory” of disease. 1885: Predicts that germ-free animals can not survive without “common microorganisms”. Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing 16S rRNA 16S SSU rRNA 16S rRNA gene V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing plantbiology.siu.edu Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA genes revealed 3 domains and a vast unappreciated diversity of microbial life You are here Carl Woese Glossary • Microbiota / microflora: the microorganisms of a particular site, habitat, or period of time. • Microbiome: the collective genomes of the microorganisms within a microbiota. • Germ-free / axenic: of a culture that is free from living organisms other than the host species. • Gnotobiotic: of an environment for rearing organisms in which all the microorganisms are either excluded or known. Current techniques for microbiome profiling Microbial community Morgan et al. (2012) Trends in -

Perfluorochemicals (Pfcs)

Biomonitoring | Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been used in many consumer products.1 The structure of these chemicals makes them very stable, hydrophobic (water-repelling), and oleophobic (oil-repelling). These unique properties have led to extensive use of PFCs in surface coating and protectant formulations for paper and cardboard packaging products; carpets; leather products; and textiles that repel water, grease, and soil. PFCs have also been used in fire-fighting foams and in the production of nonstick coatings on cookware and some waterproof clothes.1 Due in part to their chemical properties, some PFCs can remain in the environment and bioconcentrate in animals.2-8 Data from human studies suggest that some PFCs can take years to be cleared from the body.9-13 The PFCs with the highest production volumes in the United States have been perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).1 PFOS and PFOA are also two of the most frequently detected PFCs in humans.14 Other PFCs include perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), which is a member of the same chemical category as PFOS; and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), which is a member of the same chemical category as PFOA.15 Chemicals within a given PFC chemical category share similar chemical structures and uses. Although some studies have addressed PFHxS and PFNA specifically, the majority of scientific research has focused on PFOS and PFOA.15 In 2000, one of the principal perfluorochemical manufacturers, 3M, began phasing out the production of PFOA, PFOS, and PFOS-related compounds. The 3M phaseout of PFOS and PFHxS was completed in 2002, and its phaseout of PFOA was completed in 2008.16 In 2006, to address PFOA production by other manufacturers, EPA launched the 2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program, with eight companies voluntarily agreeing to reduce emissions and product content of PFOA, PFNA, and related chemicals by 95% no later than 2010. -

Chemicals and Obesity

CHEMICALS AND OBESITY While diet and exercise are important factors in the obesity epidemic, an emerging body of science demonstrates that exposures to chemical obesogens may be important contributors. A number of chemicals known to disrupt hormones also appear to affect the size and number of fat cells or hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism. The U.S. is confronting the growing rate of obesity as a major building materials. Hundreds of chemicals are recognized as public health problem. One-third of American children, and hormone disrupters that impact the delicate hormone balance two-thirds of adults, are obese or overweight.1 The direct costs in the human body. Hormone disrupters are especially harmful of treating obesity alone are $190 billion per year,2 which might because, like hormones themselves, they can exert health be as high as 16.5 percent of national health care spending.3 impacts even at minute levels of exposure and exposures in the While diet and exercise are widely recognized as important womb can have lifelong impacts. factors in the obesity epidemic, there is an emerging body of science showing that exposures to chemical obesogens may be important contributors. Obesogens are chemical agents Hormone disruption that promote fat accumulation and alter feeding behaviors A number of chemicals known to disrupt hormones also appear through various mechanisms, and we are all exposed to them to be obesogens.4,5 A 2011 National Institute of Environmental every day. Health Sciences (NIEHS) expert workshop concluded that the scientific literature supports a link between certain environ- mental chemicals and increased risk for obesity as well as Type 2 diabetes.6 Chemicals can affect the size and number of fat Widespread exposure cells or the hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism.