DRAFT Indicators Biomonitoring: Perfluorochemicals (Pfcs)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemicals in the Fourth Report and Updated Tables Pdf Icon[PDF

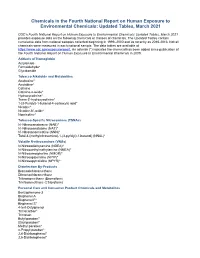

Chemicals in the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 CDC’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 provides exposure data on the following chemicals or classes of chemicals. The Updated Tables contain cumulative data from national samples collected beginning in 1999–2000 and as recently as 2015-2016. Not all chemicals were measured in each national sample. The data tables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. An asterisk (*) indicates the chemical has been added since publication of the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in 2009. Adducts of Hemoglobin Acrylamide Formaldehyde* Glycidamide Tobacco Alkaloids and Metabolites Anabasine* Anatabine* Cotinine Cotinine-n-oxide* Hydroxycotinine* Trans-3’-hydroxycotinine* 1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-butanol-4-carboxylic acid* Nicotine* Nicotine-N’-oxide* Nornicotine* Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) N’-Nitrosoanabasine (NAB)* N’-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT)* N’-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN)* Total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol) (NNAL)* Volatile N-nitrosamines (VNAs) N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)* N-Nitrosoethylmethylamine (NMEA)* N-Nitrosomorpholine (NMOR)* N-Nitrosopiperidine (NPIP)* N-Nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR)* Disinfection By-Products Bromodichloromethane Dibromochloromethane Tribromomethane (Bromoform) Trichloromethane (Chloroform) Personal Care and Consumer Product Chemicals and Metabolites Benzophenone-3 Bisphenol A Bisphenol F* Bisphenol -

And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances – Chemical Variation and Applicability of Current Fate Models

CSIRO PUBLISHING Environ. Chem. 2020, 17, 498–508 Research Paper https://doi.org/10.1071/EN19296 Investigating the OECD database of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances – chemical variation and applicability of current fate models Ioana C. Chelcea,A Lutz Ahrens,B Stefan O¨ rn,C Daniel MucsD and Patrik L. Andersson A,E ADepartment of Chemistry, Umea˚ University, SE-901 87 Umea˚, Sweden. BDepartment of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Box 7050, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden. CDepartment of Biomedical Sciences and Veterinary Public Health, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden. DRISE SP – Chemical and Pharmaceutical Safety, Forskargatan 20, 151 36 So¨derta¨lje, Sweden. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Environmental context. A diverse range of materials contain organofluorine chemicals, some of which are hazardous and widely distributed in the environment. We investigated an inventory of over 4700 organofluorine compounds, characterised their chemical diversity and selected representatives for future testing to fill knowledge gaps about their environmental fate and effects. Fate and property models were examined and concluded to be valid for only a fraction of studied organofluorines. Abstract. Many per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) have been identified in the environment, and some have been shown to be extremely persistent and even toxic, thus raising concerns about their effects on human health and the environment. Despite this, little is known about most PFASs. In this study, the comprehensive database of over 4700 PFAS entries recently compiled by the OECD was curated and the chemical variation was analysed in detail. -

Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Serum Perfluorinated Alkyl Acid Concentrations and Dental Caries Among US Adolescents (NHANES 1999–2012)

Open access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024189 on 5 February 2019. Downloaded from Cross-sectional study of the association between serum perfluorinated alkyl acid concentrations and dental caries among US adolescents (NHANES 1999–2012) Nithya Puttige Ramesh,1 Manish Arora,2 Joseph M Braun1 To cite: Puttige Ramesh N, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Arora M, Braun JM. Cross- Study objectives Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are a class sectional study of the of anthropogenic and persistent compounds that may ► Our study contributes to a gap in the literature by association between serum impact some biological pathways related to oral health. perfluorinated alkyl acid examining the relationship between perfluoroalkyl The objective of our study was to estimate the relationship concentrations and dental caries acid exposure and dental caries prevalence among between dental caries prevalence and exposure to four among US adolescents (NHANES adolescents, which, to the best of our knowledge, PFAA: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorononanoic 1999–2012). BMJ Open has not been examined before. 2019;9:e024189. doi:10.1136/ acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) and ► The strengths of our study include the large sample perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) in a nationally bmjopen-2018-024189 size (2869 participants) and the nationally repre- representative sample of US adolescents. Prepublication history and sentative nature of the National Health and Nutrition ► Setting/Design We analysed cross-sectional data from additional material for this Examination Survey (NHANES). the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from paper are available online. To ► Although we adjusted for potential confounders, 1999 to 2012 for 12–19-year-old US adolescents. -

PFAS MCL Technical Support Document

ATTACHMENT 1 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) And Letter from Dr. Stephen M. Roberts, Ph.D. dated 6/25/2019 – Findings of Peer Review Conducted on Technical Background Report June 28, 2019 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) June 28, 2019 Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii Section I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 1 Section II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Section III. Reference Dose Derivation ........................................................................................................ -

Us 2018 / 0296525 A1

UN US 20180296525A1 ( 19) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication (10 ) Pub. No. : US 2018/ 0296525 A1 ROIZMAN et al. ( 43 ) Pub . Date: Oct. 18 , 2018 ( 54 ) TREATMENT OF AGE - RELATED MACULAR A61K 38 /1709 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 38 / 1866 DEGENERATION AND OTHER EYE (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 31/ 40 ( 2013 .01 ) DISEASES WITH ONE OR MORE THERAPEUTIC AGENTS (71 ) Applicant: MacRegen , Inc ., San Jose , CA (US ) (57 ) ABSTRACT ( 72 ) Inventors : Keith ROIZMAN , San Jose , CA (US ) ; The present disclosure provides therapeutic agents for the Martin RUDOLF , Luebeck (DE ) treatment of age - related macular degeneration ( AMD ) and other eye disorders. One or more therapeutic agents can be (21 ) Appl. No .: 15 /910 , 992 used to treat any stages ( including the early , intermediate ( 22 ) Filed : Mar. 2 , 2018 and advance stages ) of AMD , and any phenotypes of AMD , including geographic atrophy ( including non -central GA and Related U . S . Application Data central GA ) and neovascularization ( including types 1 , 2 and 3 NV ) . In certain embodiments , an anti - dyslipidemic agent ( 60 ) Provisional application No . 62/ 467 ,073 , filed on Mar . ( e . g . , an apolipoprotein mimetic and / or a statin ) is used 3 , 2017 . alone to treat or slow the progression of atrophic AMD Publication Classification ( including early AMD and intermediate AMD ) , and / or to (51 ) Int. CI. prevent or delay the onset of AMD , advanced AMD and /or A61K 31/ 366 ( 2006 . 01 ) neovascular AMD . In further embodiments , two or more A61P 27 /02 ( 2006 .01 ) therapeutic agents ( e . g ., any combinations of an anti - dys A61K 9 / 00 ( 2006 . 01 ) lipidemic agent, an antioxidant, an anti- inflammatory agent, A61K 31 / 40 ( 2006 .01 ) a complement inhibitor, a neuroprotector and an anti - angio A61K 45 / 06 ( 2006 .01 ) genic agent ) that target multiple underlying factors of AMD A61K 38 / 17 ( 2006 .01 ) ( e . -

Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)

United States Office of Water EPA 822-R-16-003 Environmental Protection Mail Code 4304T May 2016 Agency Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 i Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water (4304T) Health and Ecological Criteria Division Washington, DC 20460 EPA Document Number: 822-R-16-003 May 2016 Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 ii BACKGROUND The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), as amended in 1996, requires the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to periodically publish a list of unregulated chemical contaminants known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and that may require regulation under SDWA. The SDWA also requires the Agency to make regulatory determinations on at least five contaminants on the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) every 5 years. For each contaminant on the CCL, before EPA makes a regulatory determination, the Agency needs to obtain sufficient data to conduct analyses on the extent to which the contaminant occurs and the risk it poses to populations via drinking water. Ultimately, this information will assist the Agency in determining the most appropriate course of action in relation to the contaminant (e.g., developing a regulation to control it in drinking water, developing guidance, or deciding not to regulate it). The PFOA health assessment was initiated by the Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology in 2009. The draft Health Effects Support Document for Perfluoroctanoic Acid (PFOA) was completed in 2013 and released for public comment in February 2014. -

United Nations Sc

UNITED NATIONS SC UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/INF/16 Distr.: General 2 August 2016 English only Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee Twelfth meeting Rome, 19–23 September 2015 Item 4 (d) of the provisional agenda Technical work: consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Comments and responses relating to the draft consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Note by the Secretariat As referred to in the note by the Secretariat on guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals (UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/7), the annex to the present note contains a table listing the comments and responses relating to the draft guidance. The present note, including its annex, has not been formally edited. UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/1. 030816 UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/INF/16 Annex Comments and responses relating to the draft consolidated guidance on alternatives to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its related chemicals Minor grammatical or spelling changes have been made without acknowledgment. Only substantial comments are listed. Yellow highlight indicates addition of text while green highlight indicates deletion. Source of Page Para Comments on the second draft Response Comment Austria 7 2 This statement is better placed in Chapter VII Rejected. accompanied with a justification for those “critical applications”. For clarification “where it is not currently possible without the use of PFOS” is added Austria 15 47 According to May be commercialized is revised to http://poppub.bcrc.cn/col/1413428117937/index.html “are commercialized” F-53 and F-53B have a long history of usage and have been commercialized before PFOS related Reference substances were used (cf. -

Perfluorochemicals (Pfcs)

Biomonitoring | Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) Perfluorochemicals (PFCs) are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been used in many consumer products.1 The structure of these chemicals makes them very stable, hydrophobic (water-repelling), and oleophobic (oil-repelling). These unique properties have led to extensive use of PFCs in surface coating and protectant formulations for paper and cardboard packaging products; carpets; leather products; and textiles that repel water, grease, and soil. PFCs have also been used in fire-fighting foams and in the production of nonstick coatings on cookware and some waterproof clothes.1 Due in part to their chemical properties, some PFCs can remain in the environment and bioconcentrate in animals.2-8 Data from human studies suggest that some PFCs can take years to be cleared from the body.9-13 The PFCs with the highest production volumes in the United States have been perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).1 PFOS and PFOA are also two of the most frequently detected PFCs in humans.14 Other PFCs include perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), which is a member of the same chemical category as PFOS; and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), which is a member of the same chemical category as PFOA.15 Chemicals within a given PFC chemical category share similar chemical structures and uses. Although some studies have addressed PFHxS and PFNA specifically, the majority of scientific research has focused on PFOS and PFOA.15 In 2000, one of the principal perfluorochemical manufacturers, 3M, began phasing out the production of PFOA, PFOS, and PFOS-related compounds. The 3M phaseout of PFOS and PFHxS was completed in 2002, and its phaseout of PFOA was completed in 2008.16 In 2006, to address PFOA production by other manufacturers, EPA launched the 2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program, with eight companies voluntarily agreeing to reduce emissions and product content of PFOA, PFNA, and related chemicals by 95% no later than 2010. -

Host-Directed Therapeutics for Tuberculosis: Can We Harness the Host?

Host-Directed Therapeutics for Tuberculosis: Can We Harness the Host? Thomas R. Hawn,a Alastair I. Matheson,b Stephen N. Maley,b Omar Vandalc Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USAa; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USAb; The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, Washington, USAc SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................608 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................608 OVERVIEW OF IMMUNE RESPONSE TO M. TUBERCULOSIS AND POTENTIAL HDT TARGETS..............................................................609 HDTs AND MACROPHAGE FUNCTION ....................................................................................................................609 Binding and M. tuberculosis Uptake.......................................................................................................................609 Phagosome Maturation and Function....................................................................................................................610 Phagosome acidification ..............................................................................................................................611 GTPases and phagosome maturation .................................................................................................................611 -

Phthalates and Reproduction in the Female Zebrafish (Danio Rerio)

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), phthalates and reproduction in the female zebrafish (Danio rerio) by Abiran Sritharan A Thesis Presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Integrative Biology (Reproductive Physiology) Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Abiran Sritharan, September 2017 i ABSTRACT Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), phthalates and reproduction in the female zebrafish (Danio rerio) Abiran Sritharan Advisor: Dr. Glen Van Der Kraak University of Guelph, 2017 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear transcription factors that mediate a wide array of physiological processes in mammals including reproduction. The objective of this thesis was to characterize the presence, regulation and actions of members of the PPAR family in the ovary of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gene expression of all five PPARs, pparαA, pparαB, pparβA, pparβB and pparγ, was detected in ovarian follicles at different stages of development. The expression of pparαA, pparβB and pparγ declined as the follicles developed. Human chorionic-gonadotropin, a luteinizing hormone analog, was shown to decrease gene expression of pparαA, while activators of the Protein Kinase C pathway downregulated expression of pparαA, pparαB and pparβB in full grown ovarian follicles. Intraperitoneal injections of the known PPAR ligands, diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) reduced the numbers of eggs spawned by adult female zebrafish and this was attributed to a disruption in ovulation. Fish injected with either DEHP or MEHP had reduced expression of the nuclear progesterone receptor (npr) gene, and fish injected with MEHP had reduced expression of a distintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 1 (adamts1) gene expression, two key players in the ovulation process. -

Obesogens in the Aquatic Environment an Evolutionary And

Environment International 106 (2017) 153–169 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environment International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envint Review article Obesogens in the aquatic environment: an evolutionary and toxicological MARK perspective ⁎ ⁎ ⁎ Ana Capitãoa,b, , Angeliki Lyssimachoua, Luís Filipe Costa Castroa,b, , Miguel M. Santosa,b, a CIMAR/CIIMAR- Interdisciplinary Centre of Marine and Environmental Research, University of Porto, Terminal de Cruzeiros do Porto de Leixões, Avenida General Norton de Matos, S/N, 4450-208 Matosinhos, Portugal b FCUP – Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The rise of obesity in humans is a major health concern of our times, affecting an increasing proportion of the Obesogens population worldwide. It is now evident that this phenomenon is not only associated with the lack of exercise Endocrine disruption and a balanced diet, but also due to environmental factors, such as exposure to environmental chemicals that Evolution interfere with lipid homeostasis. These chemicals, also known as obesogens, are present in a wide range of Nuclear receptor products of our daily life, such as cosmetics, paints, plastics, food cans and pesticide-treated food, among others. Lipid metabolism A growing body of evidences indicates that their action is not limited to mammals. Obesogens also end up in the Aquatic animals aquatic environment, potentially affecting its ecosystems. In fact, reports show that some environmental che- micals are able to alter lipid homeostasis, impacting weight, lipid profile, signaling pathways and/or protein activity, of several taxa of aquatic animals. Such perturbations may give rise to physiological disorders and disease. -

Abstracts Monday August 26

ABSTRACTS MONDAY AUGUST 26 KEYNOTES, SYMPOSIA, ORAL PRESENTATION SESSIONS, POSTER DISCUSSION SESSIONS, THEMATIC POSTER SESSIONS “On Air Table of contents Monday August 26, 9:00 AM – 10:00 AM ............................................................................................... 23 Keynote Lectures .................................................................................................................................. 23 Cities as unequal opportunities for good health ........................................................................................... 23 Challenges and Prospects of Environmental Epidemiology in Africa ............................................................ 24 Monday August 26 10:30 AM – 12:00 PM .............................................................................................. 25 S01: Mapping the Air Pollution Metabolome: Applications, Limitations, and the Path Forward ............... 25 Metabolic perturbations following exposures to traffic-related air pollution in a panel of commuters with and without asthma ...................................................................................................................................... 25 Traffic-Related Air Pollution Exposure and Altered Fatty Acid Oxidation Among Adolescents and Young Adults – the Interplay with Obesity .............................................................................................................. 26 The Maternal Serum Metabolome and Ambient Air Pollution Exposure during Pregnancy .......................