Basin-Scale Tidal Measurements Using Acoustic Tomography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Earth's Gravity Tide and Ocean Loading

CHINESE JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICS Vol.49, No.3, 2006, pp: 657∼670 STUDY OF EARTH’S GRAVITY TIDE AND OCEAN LOADING CHARACTERISTICS IN HONGKONG AREA SUN He-Ping1 HSU House1 CHEN Wu2 CHEN Xiao-Dong1 ZHOU Jiang-Cun1 LIU Ming1 GAO Shan2 1 Key Laboratory of Dynamical Geodesy, Institute of Geodesy and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430077, China 2 Department of Land Surveying and Geoinformatics, Hong-Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Knowloon, Hong Kong Abstract The tidal gravity observation achievements obtained in Hongkong area are introduced, the first complete tidal gravity experimental model in this area is obtained. The ocean loading characteristics are studied systematically by using global and local ocean models as well as tidal gauge data, the suitability of global ocean models is also studied. The numerical results show that the ocean models in diurnal band are more stable than those in semidiurnal band, and the correction of the change in tidal height plays a significant role in determining accurately the phase lag of the tidal gravity. The gravity observation residuals and station background noise level are also investigated. The study fills the empty of the tidal gravity observation in Crustal Movement Observation Network of China and can provide the effective reference and service to ground surface and space geodesy. Key words Hongkong area, Tidal gravity, Experimental model, Ocean loading 1 INTRODUCTION The Earth’s gravity is a science studying the temporal and spatial distribution of the gravity field and its physical mechanism. Generally, its achievements can be used in many important domains such as space science, geophysics, geodesy, oceanography, and so on. -

Title on the Observations of the Earth Tide by Means Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository On the Observations of the Earth Tide by Means of Title Extensometers in Horizontal Components Author(s) OZAWA, Izuo Bulletins - Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto Citation University (1961), 46: 1-15 Issue Date 1961-03-27 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/123706 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University DISASTER PREVENTION RESEARCH INSTITUTE BULLETIN NO. 46 MARCH, 1961 ON THE OBSERVATIONS OF THE EARTH TIDE BY MEANS OF EXTENSOMETERS IN HORIZONTAL COMPONENTS BY IZUO OZAWA KYOTO UNIVERSITY, KYOTO, JAPAN 1 DISASTER PREVENTION RESEARCH INSTITUTE KYOTO UNIVERSITY BULLETINS Bulletin No. 46 March, 1961 On the Observations of the Earth Tide by Means of Extensometers in Horizontal Components By Izuo OZAWA 2 On the Observations of the Earth Tide by Means of Extensometers in Horizontal Components By Izuo OZAWA Geophysical Institute, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Abstract The author has performed the observations of tidal strains of the earth's surface in some or several directions by means of extensometers at Osakayama observatory Kishu mine, Suhara observatory and Matsushiro observatory, and he has calculated the tide-constituents (M2, 01, etc.) of the observed strains by means of harmonic analysis. According to the results, the phase lags of M2-constituents except one in Suhara are nearly zero, whose upper and lower limits are 43' and —29°, respectively. That is the coefficients of cos 2t-terms of the strains are posi- tive value in all the azimuths, and the ones of their sin 2t-terms are much smaller than the ones of their cos 2t-terms, where t is an hour angle of hypothetical heavenly body at the observatory. -

Earth Tide Effects on Geodetic Observations

EARTH TIDE EFFECTS ON GEODETIC OBSERVATIONS by K. BRETREGER A thesis submitted as a part requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the University of New South Wales. January 1978 School of Surveying Kensington, Sydney. This is to certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other University or Institution. K. Bretreger ( i i i) ABSTRACT The Earth tide formulation is developed in the view of investigating ocean loading effects. The nature of the ocean tide load leads to a proposalfor a combination of quadratures methods and harmonic representation being used in the representation of the loading potential. This concept is developed and extended by the use of truncation functions as a means of representing the stress and deformation potentials, and the radial displacement in the case of both gravity and tilt observations. Tidal gravity measurements were recorded in Australia and Papua New Guinea between 1974 and 1977, and analysed at the International Centre for Earth Tides, Bruxelles. The observations were analysed for the effect of ocean loading on tidal gravity with a •dew to nodelling these effects as a function of space and time. It was found that present global ocean tide models cannot completely account for the observed Earth tide residuals in Australia. Results for a number of models are shown, using truncation function methods and the Longman-Farrell approach. Ocean tide loading effects were computed using a simplified model of the crustal response as an alternative to representation by the set of load deformation coefficients h~, k~. It is shown that a ten parameter representation of the crustal response is adequate for representing the deformation of the Earth tide by ocean loading at any site in Australia with a resolution of ±2 µgal provided extrapolation is not performed over distances greater than 10 3 km. -

The Earth Tide Effects on Petroleum Reservoirs

THE EARTH TIDE EFFECTS ON PETROLEUM RESERVOIRS Preliminary Study A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM ENGINEERING AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ENGINEER by Patricia C. Axditty May 197T" Approved for the Department: t-^ 7 Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies: Dean of Graduate Studies ii To my husband iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author is indebted to Professor Amos N. Nur and Professor H. J. Ramey, Jr., who suggested the research and provided help and advice throughout the project. The field data used in this work were made available by personnel of many different oil companies. The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. G. F. Kingelin from Gult Research and Development Company, Dr. C. C. Mattax and D. A. Pierce from Exxon, Dr. S. C. Swift from Cities Service Company, George B. Miller of Occidental Research Corporation, and many others who contributed to this study. Computer time was provided by Stanford University. This work was supported partly by the Stanford LBL Contract #167-3500 for the Department of Petroleum Engineering, and by the Stanford Rock Physics Project //2-BCZ-903 for the Department of Geophysics. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv ABSTRACT 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. SOME BACKGROUND ON THE STRESS-STRAIN THEORY AND THE EARTH TIDE MECHANISM 4 2.1 Stress-Strain Theory 4 2.2 General Information on Tides 14 3. THE EFFECTS OF EARTH TIDES ON OPEN WELL-AQUIFER SYSTEMS: STATE OF THE ART 22 3.1 Static Solution 24 3.2 Dynamic Solution 27 4. -

Lecture 1: Introduction to Ocean Tides

Lecture 1: Introduction to ocean tides Myrl Hendershott 1 Introduction The phenomenon of oceanic tides has been observed and studied by humanity for centuries. Success in localized tidal prediction and in the general understanding of tidal propagation in ocean basins led to the belief that this was a well understood phenomenon and no longer of interest for scientific investigation. However, recent decades have seen a renewal of interest for this subject by the scientific community. The goal is now to understand the dissipation of tidal energy in the ocean. Research done in the seventies suggested that rather than being mostly dissipated on continental shelves and shallow seas, tidal energy could excite far traveling internal waves in the ocean. Through interaction with oceanic currents, topographic features or with other waves, these could transfer energy to smaller scales and contribute to oceanic mixing. This has been suggested as a possible driving mechanism for the thermohaline circulation. This first lecture is introductory and its aim is to review the tidal generating mechanisms and to arrive at a mathematical expression for the tide generating potential. 2 Tide Generating Forces Tidal oscillations are the response of the ocean and the Earth to the gravitational pull of celestial bodies other than the Earth. Because of their movement relative to the Earth, this gravitational pull changes in time, and because of the finite size of the Earth, it also varies in space over its surface. Fortunately for local tidal prediction, the temporal response of the ocean is very linear, allowing tidal records to be interpreted as the superposition of periodic components with frequencies associated with the movements of the celestial bodies exerting the force. -

Once Again: Once Againmtidal Friction

Prog. Oceanog. Vol. 40~ pp. 7-35, 1997 © 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Pergamon Printed in Great Britain PII: S0079-6611( 97)00021-9 0079-6611/98 $32.0(I Once again: once againmtidal friction WALTER MUNK Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California-San Diego, La Jolht, CA 92093-0225, USA Abstract - Topex/Poseidon (T/P) altimetry has reopened the problem of how tidal dissipation is to be allocated. There is now general agreement of a M2 dissipation by 2.5 Terawatts ( 1 TW = 10 ~2 W), based on four quite separate astronomic observational programs. Allowing for the bodily tide dissipation of 0.1 TW leaves 2.4 TW for ocean dissipation. The traditional disposal sites since JEFFREYS (1920) have been in the turbulent bottom boundary layer (BBL) of marginal seas, and the modern estimate of about 2.1 TW is in this tradition (but the distribution among the shallow seas has changed radically from time to time). Independent estimates of energy flux into the mar- ginal seas are not in good agreement with the BBL estimates. T/P altimetry has contributed to the tidal problem in two important ways. The assimilation of global altimetry into Laplace tidal solutions has led to accurate representations of the global tides, as evidenced by the very close agreement between the astronomic measurements and the computed 2.4 TW working of the Moon on the global ocean. Second, the detection by RAY and MITCHUM (1996) of small surface manifestation of internal tides radiating away from the Hawaiian chain has led to global estimates of 0.2 to 0.4 TW of conversion of surface tides to internal tides. -

Tide 1 Tides Are the Rise and Fall of Sea Levels Caused by the Combined

Tide 1 Tide The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, Nova Scotia during high tide Nova Scotia during low tide Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon and the Sun and the rotation of the Earth. Most places in the ocean usually experience two high tides and two low tides each day (semidiurnal tide), but some locations experience only one high and one low tide each day (diurnal tide). The times and amplitude of the tides at the coast are influenced by the alignment of the Sun and Moon, by the pattern of tides in the deep ocean (see figure 4) and by the shape of the coastline and near-shore bathymetry.[1] [2] [3] Most coastal areas experience two high and two low tides per day. The gravitational effect of the Moon on the surface of the Earth is the same when it is directly overhead as when it is directly underfoot. The Moon orbits the Earth in the same direction the Earth rotates on its axis, so it takes slightly more than a day—about 24 hours and 50 minutes—for the Moon to return to the same location in the sky. During this time, it has passed overhead once and underfoot once, so in many places the period of strongest tidal forcing is 12 hours and 25 minutes. The high tides do not necessarily occur when the Moon is overhead or underfoot, but the period of the forcing still determines the time between high tides. -

Sea Level - Updated August 2016

Climate Change Indicators in the United States: Sea Level www.epa.gov/climate-indicators - Updated August 2016 Sea Level This indicator describes how sea level has changed over time. The indicator describes two types of sea level changes: absolute and relative. Background As the temperature of the Earth changes, so does sea level. Temperature and sea level are linked for two main reasons: 1. Changes in the volume of water and ice on land (namely glaciers and ice sheets) can increase or decrease the volume of water in the ocean (see the Glaciers indicator). 2. As water warms, it expands slightly—an effect that is cumulative over the entire depth of the oceans (see the Ocean Heat indicator). Changing sea levels can affect human activities in coastal areas. Rising sea level inundates low-lying wetlands and dry land, erodes shorelines, contributes to coastal flooding, and increases the flow of salt water into estuaries and nearby groundwater aquifers. Higher sea level also makes coastal infrastructure more vulnerable to damage from storms. The sea level changes that affect coastal systems involve more than just expanding oceans, however, because the Earth’s continents can also rise and fall relative to the oceans. Land can rise through processes such as sediment accumulation (the process that built the Mississippi River delta) and geological uplift (for example, as glaciers melt and the land below is no longer weighed down by heavy ice). In other areas, land can sink because of erosion, sediment compaction, natural subsidence (sinking due to geologic changes), groundwater withdrawal, or engineering projects that prevent rivers from naturally depositing sediments along their banks. -

Sea Level Changes Monitoring Using GNSS Technology – a Review of Recent Efforts

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk ISSN: 0001-5113 ACTA ADRIAT., REVIEW articLE AADRAY 55(2): 145 - 162, 2014 Sea level changes monitoring using GNSS technology – a review of recent efforts Karol DAWIDOWICZ University of Warmia and Mazury, ul. Oczapowskiego 1, 10-089 Olsztyn, Poland Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Sea level is traditionally observed with tide gauges (TG). These measurements are relative to the Earth’s crust. To improve the understanding of sea level changes it is necessary to perform measure- ments with respect to the Earth’s center of mass. This can be done with satellite techniques. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) is a tool that can solves several hundred kilometers vectors with centimeter level of accuracy and can measure point height changes relative to the refer- ence ellipsoid WGS84 which is centred at the actual center of mass of the Earth. Although in the past two decades GNSS were used in almost every field of geodetic measurements, it is still almost not in use in the field of sea level monitoring. Attempts of using GNSS equipped buoys for the determina- tion of precise sea level (at centimeter level) were successful and suggest that GNSS is capable of replacing the conventional tide gauges. A review of recent efforts made on observing sea level variations using data from a GNSS receiv- ers were presented here. Furthermore, presented review resulted in a conclusion that the use of a GNSS based Tide Gauge (GNSSTG) system for the determination of sea level changes is possible, and that its accuracy level (averaged) is equal to a float based tide gauge. -

PASI Tide Lecture

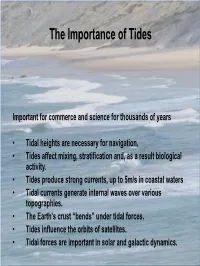

The Importance of Tides Important for commerce and science for thousands of years • Tidal heights are necessary for navigation. • Tides affect mixing, stratification and, as a result biological activity. • Tides produce strong currents, up to 5m/s in coastal waters • Tidal currents generate internal waves over various topographies. • The Earth's crust “bends” under tidal forces. • Tides influence the orbits of satellites. • Tidal forces are important in solar and galactic dynamics. The Nature of Tides “The truth is, the word "tide" as used by sailors at sea means horizontal motion of the water; but when used by landsmen or sailors in port, it means vertical motion of the water.” “One of the most interesting points of tidal theory is the determination of the currents by which the rise and fall is produced, and so far the sailor's idea of what is most noteworthy as to tidal motion is correct: because before there can be a rise and fall of the water anywhere it must come from some other place, and the water cannot pass from place to place without moving horizontally, or nearly horizontally, through a great distance. Thus the primary phenomenon of the tides is after all the tidal current; …” The Tides, Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) – 1882, Evening Lecture To The British Association TIDAL HYDRODYNAMICS AND MODELING Dr. Cheryl Ann Blain Naval Research Laboratory Stennis Space Center, MS, USA [email protected] Pan-American Studies Institute, PASI Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, 2–13 January, 2013 — Valparaíso, Chile -

The Australian National University1

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY1 SCIENCEWISESpring 2013 Volume 10 No.4 - Spring 2013 2 04 How did we get here? Can the mathematics of waves explain the origin of life? CONTENTS 6 Inspired by nature Better pathways to new medical compounds 8 Drifting off Are GPS coordinates shifting 10 beneath our feet? Science magnet How a unique facility is attracting scientists to Australia 12 A mysterious sequence How an antiquated rule of thumb may identify new Earths ScienceWise 3 For Bode-ing I’ve said this before, but hey, I’m the Editor so I can say it again. In science, observation is king and any theory that doesn’t fit the observations, however cherished, is wrong! I can’t deny it irritates me when I hear people proclaim that something is impossible because their pet theory precludes it, even though the phenomena has been clearly observed. So I’ve enjoyed covering a piece of Dr Tim Wetherell research in this edition that’s given some credibility back to a centuries old idea; Bode’s law or more correctly the Titus-Bode relation. It’s just a rule of thumb that predicts the spacing of planets orbiting a star which was popular in the 18th century but rapidly fell out of favour largely because there’s no good theoretical justification for it. CONTENTS A couple of my colleagues up at Mt Stromlo Observatory have just shown that this old rule of thumb actually works superbly well for many other solar systems outside our own. Yeah for Bode’s law! When you think about it, any given spinning accretion disc around any forming star is likely to have very similar properties to any other. -

Numerical Modelling of the Tides in the Caspian

https://doi.org/10.5194/os-2019-88 Preprint. Discussion started: 31 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Numerical modelling of the tides in the Caspian Sea Igor Medvedev1, 2, Evgueni Kulikov1, Isaac Fine3 1Shirhov Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 2Fedorov Institute of Applied Geophysics, Moscow, Russia 5 3Institute of Ocean Sciences, Sidney, B.C., Canada Correspondence to: Igor Medvedev ([email protected]) Abstract. The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed basin on the Earth and a unique object for analysis of tidal dynamics. The Caspian Sea has independent tides only, which are generated directly by tide-forming forces. Using the Princeton Ocean Model (POM), we examine the spatial 10 and temporal features of tidal dynamics in the Caspian Sea in detail. We present tidal charts for amplitudes and phase lags of the major tidal harmonics, form factor, tidal range and velocity of tidal currents. Semidiurnal tides in the Caspian Sea are determined by a Taylor amphidromic system with counterclockwise rotation. The largest M2 amplitude is 6 cm and is located in the Turkmen Bay. The Absheron Peninsula splits this system into two separate amphidromies with 15 counterclockwise rotation to the north and to the south of it. The maximum K1 amplitudes (up to 0.7–0.8 cm) are located in: 1) the southeastern part of the Caspian Sea, 2) the Türkmenbaşy Gulf, 3) the Mangyshlak Bay, and 4) the Kizlyar Bay. The semidiurnal tides prevail over diurnal tides in the Caspian Sea. The maximum tidal range has been observed in the Turkmen Bay, up to 21 cm.