World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programmation Hebdomadaire Des Marchés

Cellule Technique de Suivi et d’Appui à la Gestion de la Sécurité Alimentaire (CT-SAGSA) Programmation Hebdomadaire des marchés Semaine du lundi 15 au dimanche 21 mars 2021 Jour/Département Marchés lundi 15 mars 2021 Atacora Tokotoko, Tchabikouma, Tanéka-Koko, Kouaba, Tanguiéta, Manta Donga Djougou Alibori Banikoara, Goumori Borgou Gamia, Sinendé-Centre, Guéssou-Bani, Sèkèrè, Tchaourou, [Bétail] Tchaourou, Biro Collines [Bétail] Savalou (Tchetti), Tchetti, Savalou, Savè Zou Abomey (Houndjro), Djidja, Dovi-Dovè, Za-Hla, Houandougon, Domè, Setto, Oumbèga, Covè, Dan Couffo Tchito, Klouékanmè Mono Honhoué, Lokossa, Kpinnou, Akodéha Plateau [Bétail] Kétou (Iwoyé), Ikpinlè, Kétou, Yoko, Pobè Ouémé Affamè, [Bétail] Sèmè-Podji, Hozin, Adjarra, Azowlissè Atlantique Toffo, Kpassè, Hadjanaho, Zè, Godonoutin, Sey (dans Toffo), Tori-Gare, Ahihohomey (dans Abomey- Calavi), Sékou mardi 16 mars 2021 Atacora Toucountouna, Boukoumbé, Kouandé Donga Bariyénou, [Bétail] Djougou (Kolokondé), Kolokondé, Kikélé, Kassoua-Allah Alibori Sori, Sompérékou, Kandi Borgou Tchikandou, Fo-Bouré, [Bétail] Parakou (ASELCOP) Collines Sowigandji, Lahotan, Dassa-Zoumè, Aklankpa, Bantè Zou Agouna, Kpokissa, Ouinhi Couffo Djékpétimey, Dogbo Mono Danhoué Plateau Toubè, [Bétail] Kétou (Iwoyé), Aba, Adigun, Ifangni, Akitigbo, Efêoutê Ouémé Kouti, [Bétail] Sèmè-Podji, Ahidahomè (Porto-Novo), Gbagla-Ganfan, Ouando, Gbangnito, Vakon- Attinsa Atlantique Tori-Bossito, Déssa, Zinvié, Tokpadomè, Hêvié-Djêganto, Saint Michel d’Allada, Agbata mercredi 17 mars 2021 Atacora Natitingou, Tobré, -

Caractéristiques Générales De La Population

République du Bénin ~~~~~ Ministère Chargé du Plan, de La Prospective et du développement ~~~~~~ Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique Résultats définitifs Caractéristiques Générales de la Population DDC COOPERATION SUISSE AU BENIN Direction des Etudes démographiques Cotonou, Octobre 2003 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1: Population recensée au Bénin selon le sexe, les départements, les communes et les arrondissements............................................................................................................ 3 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de KANDI selon le sexe et par année d’âge ......................................................................... 25 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de NATITINGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge......................................................................................... 28 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de OUIDAH selon le sexe et par année d’âge............................................................................................................ 31 Tableau G02A&B :Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de PARAKOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge (Commune à statut particulier).................................................... 35 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de DJOUGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge .................................................................................................... 40 Tableau -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

2021 Liste Des Candidats Mathi

MINISTERE DU TRAVAIL ET DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Fraternité - Justice - Travail ********** DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE DIRECTION CHARGEE DU RECRUTEMENT DES AGENTS DE L'ETAT Communiqué 002/MTFP/DC/SGM/DGFP/DRAE/STCD/SA du 26 mars 2021 CENTRE: LYCéE MATHIEU BOUKé LISTE D'AFFICHAGE DES CANDIDATS N° TABLE. NOM ET PRENOMS DATE ET LIEU DE NAISSANCE CORPS SALLE 0468-A16-1907219 Mlle ABDOU Affoussath 19/11/1997 à Parakou Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 16 0533-A18-1907218 Mlle ABDOU Rissikath 17/08/1988 à Lokossa Secrétaires des Services Administratifs(B3) A 18 0219-A08-1907213 M. ABDOULAYE Mohamadou Moctar 05/11/1987 à Niamey Techniciens Supérieurs de la Statistique A 8 0406-A14-1907219 Mlle ABIOLA Adéniran Adélèyè Taïbatou 30/06/1989 à Savè Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 14 0470-A16-1907219 M. ABISSIN Mahugnon Judicaël 04/04/1998 à Allahé Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 16 0281-A10-1907220 Mlle ABOUBOU ALIASSOU Silifatou 04/10/1990 à Ina Contrôleurs de l'Action Sociale (B1) A 10 0030-A01-1907189 M. ADAM Abdouramane 22/02/1988 à Penelan Administrateurs:Gestion des Marchés A 1 Publics 0233-A08-1907213 M. ADAM Ezéchiel 05/06/1997 à Parakou Techniciens Supérieurs de la Statistique A 8 0177-A06-1907203 M. ADAMOU Charif 20/11/1995 à Parakou Attachés des Services Financiers A 6 0448-A15-1907219 M. ADAMOU Kamarou 18/01/1996 à Kandi Contrôleurs des Services Financiers (B3) A 15 0135-A05-1907203 M. ADAMOU Samadou 20/02/1989 à Nikki Attachés des Services Financiers A 5 0568-A19-1907216 Mlle ADAMOU Tawakalith 03/05/1991 à Lozin Techniciens d'Hygiène et d'Assainissement A 19 0584-A20-1907216 M. -

Benin• Floods Rapport De Situation #13 13 Au 30 Décembre 2010

Benin• Floods Rapport de Situation #13 13 au 30 décembre 2010 Ce rapport a été publié par UNOCHA Bénin. Il couvre la période du 13 au 30 Décembre. I. Evénements clés Le PDNA Team a organisé un atelier de consolidation et de finalisation des rapports sectoriels Le Gouvernement de la République d’Israël a fait don d’un lot de médicaments aux sinistrés des inondations La révision des fiches de projets du EHAP a démarré dans tous les clusters L’Organisation Ouest Africaine de la Santé à fait don d’un chèque de 25 millions de Francs CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations au Bénin L’ONG béninoise ALCRER a fait don de 500.000 F CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations 4 nouveaux cas de choléra ont été détectés à Cotonou II. Contexte Les eaux se retirent de plus en plus et les populations sinistrés manifestent de moins en moins le besoin d’installation sur les sites de déplacés. Ceux qui retournent dans leurs maisons expriment des besoins de tentes individuelles à installer près de leurs habitations ; une demande appuyée par les autorités locales. La veille sanitaire post inondation se poursuit, mais elle est handicapée par la grève du personnel de santé et les lots de médicaments pré positionnés par le cluster Santé n’arrivent pas à atteindre les bénéficiaires. Des brigades sanitaires sont provisoirement mises en place pour faire face à cette situation. La révision des projets de l’EHAP est en cours dans les 8 clusters et le Post Disaster Needs Assessment Team est en train de finaliser les rapports sectoriels des missions d’évaluation sur le terrain dans le cadre de l’élaboration du plan de relèvement. -

Rapport National De Spatialisation Des Cibles Prioritaires Des Objectifs De Développement Durable Au Bénin

+ . Rapport national de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des Objectifs de Développement Durable au Bénin 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développe- ment Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentrali- Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Déve- sation et au Développement Com- loppement (PASD / PNUD) munal (PDDC / GIZ) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'en- Fonds des Nations unies pour la popu- fance (UNICEF) lation (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils 0 Tables des matières PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 AVANT-PROPOS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 SIGLES ET ACRONYMES ........................................................................................................................................................7 RESUME EXECUTIF .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 SECTION 1 : INTRODUCTION GENERALE.................................................................................................................. -

BENIN-2 Cle0aea97-1.Pdf

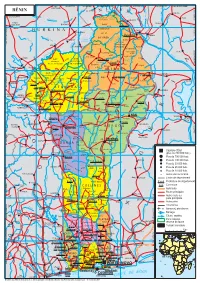

1° vers vers BOTOU 2° vers NIAMEY vers BIRNIN-GAOURÉ vers DOSSO v. DIOUNDIOU vers SOKOTO vers BIRNIN KEBBI KANTCHARI D 4° G vers SOKOTO vers GUSAU vers KONTAGORA I E a BÉNIN N l LA TAPOA N R l Pékinga I o G l KALGO ER M Rapides a vers BOGANDÉ o Gorges de de u JE r GA Ta Barou i poa la Mékrou KOULOU Kompa FADA- BUNZA NGOURMA DIAPAGA PARC 276 Karimama 12° 12° NATIONAL S o B U R K I N A GAYA k o TANSARGA t U DU W o O R Malanville KAMBA K Ka I bin S D É DU NIGER o ul o M k R G in u a O Garou g bo LOGOBOU Chutes p Guéné o do K IB u u de Koudou L 161 go A ZONE vers OUAGADOUGOU a ti r Kandéro CYNÉGÉTIQUE ARLI u o KOMBONGOU DE DJONA Kassa K Goungoun S o t Donou Béni a KOKO RI Founougo 309 JA a N D 324 r IG N a E E Kérémou Angaradébou W R P u Sein PAMA o PARC 423 ZONE r Cascades k Banikoara NATIONAL CYNÉGÉTIQUE é de Sosso A A M Rapides Kandi DE LA PENDJARI DE L'ATAKORA Saa R Goumon Lougou O Donwari u O 304 KOMPIENGA a Porga l é M K i r A L I B O R I 11° a a ti A j 11° g abi d Gbéssé o ZONE Y T n Firou Borodarou 124 u Batia e Boukoubrou ouli A P B KONKWESSO CYNÉGÉTIQUE ' Ségbana L Gogounou MANDOURI DE LA Kérou Bagou Dassari Tanougou Nassoukou Sokotindji PENDJARI è Gouandé Cascades Brignamaro Libant ROFIA Tiélé Ede Tanougou I NAKI-EST Kédékou Sori Matéri D 513 ri Sota bo li vers DAPAONG R Monrou Tanguiéta A T A K O A A é E Guilmaro n O Toukountouna i KARENGI TI s Basso N è s u Gbéroubou Gnémasson a Î o u è è è É S k r T SANSANN - g Kouarfa o Gawézi GANDO Kobli A a r Gamia MANGO Datori m Kouandé é Dounkassa BABANA NAMONI H u u Manta o o Guéssébani -

En Téléchargeant Ce Document, Vous Souscrivez Aux Conditions D’Utilisation Du Fonds Gregory-Piché

En téléchargeant ce document, vous souscrivez aux conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché. Les fichiers disponibles au Fonds Gregory-Piché ont été numérisés à partir de documents imprimés et de microfiches dont la qualité d’impression et l’état de conservation sont très variables. Les fichiers sont fournis à l’état brut et aucune garantie quant à la validité ou la complétude des informations qu’ils contiennent n’est offerte. En diffusant gratuitement ces documents, dont la grande majorité sont quasi introuvables dans une forme autre que le format numérique suggéré ici, le Fonds Gregory-Piché souhaite rendre service à la communauté des scientifiques intéressés aux questions démographiques des pays de la Francophonie, principalement des pays africains et ce, en évitant, autant que possible, de porter préjudice aux droits patrimoniaux des auteurs. Nous recommandons fortement aux usagers de citer adéquatement les ouvrages diffusés via le fonds documentaire numérique Gregory- Piché, en rendant crédit, en tout premier lieu, aux auteurs des documents. Pour référencer ce document, veuillez simplement utiliser la notice bibliographique standard du document original. Les opinions exprimées par les auteurs n’engagent que ceux-ci et ne représentent pas nécessairement les opinions de l’ODSEF. La liste des pays, ainsi que les intitulés retenus pour chacun d'eux, n'implique l'expression d'aucune opinion de la part de l’ODSEF quant au statut de ces pays et territoires ni quant à leurs frontières. Ce fichier a été produit par l’équipe des projets numériques de la Bibliothèque de l’Université Laval. Le contenu des documents, l’organisation du mode de diffusion et les conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché peuvent être modifiés sans préavis. -

Departements Zou - Collines 350000 400000 450000

DEPARTEMENTS ZOU - COLLINES 350000 400000 450000 DEPARTEMENT DU BORGOU E E E Ogoutèdo E ! E E E E E EE E E E Toui !( E E ! E Assahou E E E E E E DEPARTEMENT DE LA DONGA E E E E E E E E 950000 Kèmon E 950000 E !( ! Okoutaossé E E !F E E !( Kilibo E E Idadjo ! E E E E E E E E E 24 E E E E E E 8 E 1 E E !F Odougba E Gbanlin E E !( !( !F Pira ! Ifomon !( E E Banon ! E E H! OUESSE ! E E Yaoui E E 23 E E E E E E E E E E !( Akpassi E E E E E E Gobè ! . !F E E !( Djagbalo E Adja Pira ! ! E Anséké E !F E E H! BANTE E E Kokoro E Challa-Ogoyi !( ! E E E E Lougba E !( E E !( Koko 5 E E 2 E E E E ! Sowignandji E E E E E E R E E E E E E E E E P O E E k R !( Djègbé p U E E a r a E Agoua E !( E B E E P E ! Gogoro L E E E U E I E E B E Q E E Kaboua E L E !( U E E E O I E E U E E !( E M E Q E Aklampa 2 E 5 E E ! U E Alafia F E E ! Gbanlin Hansoe E E 9 E E 5 E E D E E E D Otola Atokoligbé E E E !( !( E U E E R E 900000 E 900000 E A !( E E Gbédjè Gouka ! Assanté !( E T E ! Ourogui L E E O E E E E E G E E O E E E ! D Yagbo E E U E Amou ! Hoko E E Miniki ! ! !( E E Kpataba E E Oké Owo !( N E !F Gbèrè E ! E H! SAVE E I E E E !( Doumè G E !( E Ouèdèmè Mangoumi 9 E !( 2 E Gobé E E !( ! E E ! Kanahoun ! Iroukou ! Doyissa Lahotan Tio!( R E E E I !F E E Agramidjodji H! E E ! A ! GLAZOUE Akongbèré E E E Attakè !( E E Kpakpaza Ouèssè !( Zafé !( E E !( E E F E ! 17 E Monkpa SAVALOU H! E E !( E E E E 30 ! E E E Igoho E Kpakpassa !( O E ! 3 p E ! Logozohè 2 Djabata k E E a ra E E Gomè E E !( Sokponta !( E E ! Obikoro Odo Agbon E E ! ! E E Akoba E E Miniffi Légende Kèrè -

Villages Arrondissement D~GARADEBOU: 14 Villages 1

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE Loi n° 2013-05 DU 27 MAI2013 portant création, organisation, attributions et fonctionnement des unités administratives locales en République du Bénin. L'Assemblée Nationale a délibéré et adopté en sa séance du 15 février 2013. Suite la Décision de conformité à la Constitution DCC 13-051 du 16 mai 2013, Le Président de la République Promulgue la loi dont la teneur suit : TITRE PREMIER DES DISPOSITIONS GENERALES Article 1er : Conformément aux dispositions de l'article 33 de la loi n° 97-028 du 15 janvier 1999 portant organisation de l'administration territoriale en République du Bénin, la commune est démembrée en unités administratives locales sans personnalité juridique ni autonomie financière. Ces unités administratives locales qui prennent les dénominations d'arrondissement, de village ou de quartier de ville sont dotées d'organes infra communaux fixés par la présente loi. Article 2 : En application des dispositions des articles 40 et 46 de la loi citée à l'article 1er, la présente loi a pour objet : 1- de déterminer les conditions dans lesquelles les unités administratives locales mentionnées à l'article 1er sont créées; 2- de fixer la formation, le fonctionnement, les compétences du conseil d'arrondissement et du conseil de village ou quartier de ville d'une part et le statut et les attributions du chef d'arrondissement, du chef de village ou quartier de ville d'autre part. Article 3: Conformément aux dispositions de l'article 4 de la loi n° 97-029 du 15 janvier 1999 portant organisation des communes en République du Bénin, la commune est divisée en arrondissements. -

2154-IJBCS-Article-Gilbert Tite Layeye

Available online at http://ajol.info/index.php/ijbcs Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 8(6): 2786-2803, December 2014 ISSN 1997-342X (Online), ISSN 1991-8631 (Print) Original Paper http://indexmedicus.afro.who.int Relation eau de ruissellement et eau des sources et forages artésiens dans la région Zagnanado-Zogbodomey au Bénin : Approche couplée (pollution microbiologique – télédétection) Gilbert Tite LALÈYÊ 1*, Expédit W. VISSIN 2, Christophe Sègbédji HOUSSOU 2 et Patrick EDORH 3 1École Doctorale Pluridisciplinaire "Espaces, Cultures et Développement", Faculté des Lettres, Arts et Sciences Humaines, Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Cotonou, Benin. 2Laboratoire Pierre Pagney – Climat-Eau-Écosystèmes-Développement Durable (LACEEDE) Faculté des Lettres, Arts et Sciences Humaines, Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Cotonou, Benin. 3Centre Interfacultaire de Formation et de Recherche en Environnement pour un Développement Durable (CIFRED), Laboratoire de Biochimie et de Biologie cellulaire, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Benin. *Auteur correspondant : E-mail : [email protected]; 04 BP 848 Cotonou, Benin ; Tel.: 229 97 53 00 04 RESUME La région Zagnanado-Zogbodomey constituée de grandes dépressions et de vallée a été retenue pour mieux comprendre l’influence des eaux de ruissellement sur la qualité des eaux souterraines des aquifères continus du Bassin sédimentaire côtier. A partir d’analyses microbiologiques portant sur des échantillons d’eau prélevés à la fois au niveau des sources et forages artésiens, la signature microbienne de chaque système hydrique a été établie. Les sources et forages artésiens sont plus affectés pendant la saison pluvieuse que la saison sèche, par la présence de germes bactériologiques. La présence de coliformes totaux et de coliformes fécaux dans l’eau des échantillons révèle que la contamination provient de la surface. -

NORD DU BENIN) Une Analyse Politique Suite À Des Interprétations Des Événements De Février 1996 À Tanguiéta

Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien Department of Anthropology and African Studies Arbeitspapiere / Working Papers Nr. 20 Tilo Grätz ADMINISTRATION ETATIQUE ET SOCIETE LOCALE A TANGUIETA (NORD DU BENIN) Une analyse politique suite à des interprétations des événements de février 1996 à Tanguiéta 2003 The Working Papers are edited by Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Forum 6, D-55099 Mainz, Germany. Tel. +49-6131-392.3720, Email: [email protected]; http://www.uni-mainz.de/~ifeas Geschäftsführender Herausgeber/ Managing Editor: Thomas Bierschenk ([email protected]) ADMINISTRATION ETATIQUE ET SOCIETE LOCALE A TANGUIETA (NORD DU BENIN) Une analyse politique suite à des interprétations des événements de février 1996 à Tanguiéta Tilo Grätz1 Sommaire: 1. Introduction...............................................................................................................................2 2. Morts, héros, vengeance. Essai de reconstruction des evenements de fevrier 1996 à Tanguiéta....................................................................................................................................2 3. Analyse: état, champ politique local et discours populaires.....................................................4 4. Retrospective: changements historiques et la crise generale actuelle de legitimite de l'état ..26 5. Perception generale des changements dans l'histoire de la commune ....................................47 6. Resumé: aspects historiques de la relation