Some Ancient Suffolk Parochial Libraries J. A. Fitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[SUFFOLK. J VET 1076 (POST OFFICE VETERINARY SURGEONS · Welham .Frederick Thomas,M.R.C.V.S.L

[SUFFOLK. J VET 1076 (POST OFFICE VETERINARY SURGEONS · Welham .Frederick Thomas,M.R.c.v.s.L. Hiles Gcorge, 16 Whiting street, Bury · Stratford St. Mary, Colchester St. Edmund's ArnoldA~dermn. Thoroughfare, W oodbdg Whayman Owen, Regent st. Stowmarket t Bir kle Bros. 19 St. Peter's st. Ipswich Auger Richard, Walpole, Halesworth Whiteman Artbr.Mendlesham, Stonham Brabrook Arthur, 33 Hisbygate street, Brown & .G?dbold, 54 Friars st. Sudbury Wiffin Wm. ·woolpit, Bury St. Edmund's Bury St. Edmund's Burch William, Mendlesham, Stonham Wright Charles, Trimley St. Martin, Brown Robt. 6 St. Matthew's st. Ipswich Churchyard James, Eyke, Woodbridge Bury St. Edmund's tBrown Williarn, St.l\Iary's st. Bungay C,Ievcland J ames, lll~bur~ate st. Beccles Wright Wm. Balls, Hollesley, Woodbrdg Buck Thomas, 7 5 Fore street, St. Cleveland Robert, Wangford Clement's, Ipswich Cleveland Wm. CarltonColville,I~owestft VOLUNTEER COBPS. Bullock Edwd. A. Sheepgate st. Beccles Cleveland William, Westhall, Wangford Suffolk Artillery Volunteers (4th) (R. J. Burditt Mrs. Elizabeth, 1'horougbfare, Coe Walter, ,'j St.Andrew'sstreetnorth, Metcalfe, captain; T. M. Read & W. Woodbridge Bury St. Edmund's Moore, lieutenants; Corporal Charles Burgess Charles Smith, 42 Tavern Coe 'V alter Brown, M.R.c.v.s. Stanton, Clarke,drill instructor); orderly room, street, Ipswich Bury St. Edmund's Newgate street, Bcccles tBurrowsA.Stradbroke,,VickharnMarkt Cornish Henry & Son, Worlingworth, Suffolk Rifle Volunteers (1st) 2nd Bat- Hurrows James, 10 James street, Bird's Wickham ~Iarket talion (J. P. Cobbold, captain corn- gardens, Ipswich Crick John, Haverhill, Newmarket mandant; SterlingWesthorp,captain; Buxton William, High street, Laven- Crook Augustus, Bardolfe road, Bungay J. -

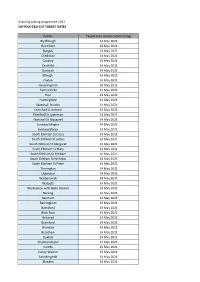

Grass Cutting 2021 Target Dates (SCC Website).Xlsx

Grassing cutting programme 2021 SUFFOLK C&U CUT TARGET DATES Parish: Target date (week commencing) Blythburgh 24 May 2021 Bramfield 24 May 2021 Bungay 24 May 2021 Chediston 24 May 2021 Cookley 24 May 2021 Cratfield 24 May 2021 Dunwich 24 May 2021 Ellough 24 May 2021 Flixton 24 May 2021 Heveningham 24 May 2021 Homersfield 24 May 2021 Hoo 24 May 2021 Huntingfield 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St John 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Andrew 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Lawrence 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Margaret 24 May 2021 Linstead Magna 24 May 2021 Linstead Parva 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Cross 24 May 2021 South Elmham St James 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Margaret 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Mary 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Michael 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Nicholas 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Peter 24 May 2021 Thorington 24 May 2021 Ubbeston 24 May 2021 Walberswick 24 May 2021 Walpole 24 May 2021 Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet 24 May 2021 Barking 24 May 2021 Barnham 24 May 2021 Barningham 24 May 2021 Battisford 24 May 2021 Beck Row 24 May 2021 Belstead 24 May 2021 Bramford 24 May 2021 Brandon 24 May 2021 Brantham 24 May 2021 Buxhall 24 May 2021 Chelmondiston 24 May 2021 Combs 24 May 2021 Coney Weston 24 May 2021 East Bergholt 24 May 2021 Elveden 24 May 2021 Eriswell 24 May 2021 Erwarton 24 May 2021 Euston 24 May 2021 Fakenham Magna 24 May 2021 Flowton 24 May 2021 Freston 24 May 2021 Great Blakenham 24 May 2021 Great Bricett 24 May 2021 Great Finborough 24 May 2021 Harkstead 24 May 2021 Harleston 24 May 2021 Holbrook 24 May 2021 Honington 24 May 2021 Hopton -

SEBC Planning Applications 31/18

LIST 31 03 August 2018 Applications Registered between 30/07/2018 – 03/08/2018 ST EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected during normal office hours on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk Representation should be made in writing, quoting the reference number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/18/1504/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - The Old Rectory VALID DATE: 12no Yew (T2 - T9 and T12-T15 on plan) - Up Street 01.08.2018 Reduce length of branches on south side of Bardwell trees by up to 1metre. Bury St Edmunds EXPIRY DATE: Suffolk 12.09.2018 APPLICANT: Mr David Ruffles IP31 1AA WARD: Bardwell CASE OFFICER: Falcon Saunders GRID REF: PARISH: Bardwell 594315 273777 DC/18/1337/FUL Planning Application - 1 no. marquee within Barnardiston Hall VALID DATE: grounds of school (retrospective) Preparatory School 30.07.2018 Hall Road APPLICANT: Col Keith Boulter Barnardiston EXPIRY DATE: AGENT: Revell Architecture And Engineering Suffolk 29.10.2018 - Mr John Roadley-Battin CB9 7TG WARD: Kedington CASE OFFICER: Kerri Cooper GRID REF: PARISH: Barnardiston 571299 250324 DC/18/1512/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - (i) The Bellows VALID DATE: 1no. Silver Birch (T1 on plan) - Fell and (ii) Blacksmith Lane 02.08.2018 7no. -

Little Thurlow

1. Parish: Little Thurlow Meaning: Famous tumulus or assembly hill 2. Hundred: Risbridge Deanery: Clare (–1884), Thurlow (1884–1916), Newmarket (1916–1972), Clare (1972–) Union: Risbridge RDC/UDC: (W. Suffolk) Clare RD (–1974), St Edmundsbury DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Risbridge Petty Sessional Division Haverhill County Court District 3. Area: 1,413 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Slowly permeable calcareous/ non-calcareous clay soils, slight risk water erosion b. Deep well drained fine loam, coarse loam and sand soils, locally flinty and in places over gravel, slight risk water erosion 5. Types of farming: 1086 Thurlow: 26 acres meadow, wood for 86 pigs, 10 cattle, 36 pigs, 46 sheep, 33 goats 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region, mainly pasture, meadow, engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig-keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. Also has similaritieis with sheep-corn region where sheep are main fertilizing agent, bred for fattening, barley main cash crop. 1804 Young: 1818 Marshall: Wide variations of crops and management techniques including summer fallow and preparation for corn products and rotation of turnip, barley, clover, wheat on lighter lands 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley, beans, roots 1 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet 6. Enclosure: 7. Settlement: 1960 Small well spaced development mainly along road to Great Thurlow (includes Pound Green, the school and the site of the Hall). Church situated slightly to east of settlement on Cowlinge Road. Secondary settlement at Lt. Thurlow Green. Scattered farms. Inhabited houses: 1674 – 23, 1801 – 48, 1851 – 99, 1871 – 94, 1901 – 80, 1951 – 83, 1981 – 84 8. -

Job 134380 Type

Delightful Grade II Listed country house Caters Farm, Cowlinge, Newmarket, Suffolk CB8 9HP Freehold Rural location with superb far reaching views • Renovated and extended former farmhouse with versatile accommodation • Stunning vaulted drawing room • Useful range of outbuildings Local information About this property • Picturesque village located in Caters Farm is a Grade II listed the south-west corner of Suffolk former farmhouse believed to close to the Cambridgeshire date from the late 16th Century border. which has been extended over the years to provide a very • Approximately 5.5 miles south welcoming and comfortable east of Newmarket and 12 miles family home. It was relatively south west of the historic town of recently listed (2001) and Bury St Edmunds, is surrounded following a detailed inspection by rolling countryside with a from a local historian, it was village gastro pub at its heart. suggested that the original plan of the house was “clear but • The high tech University City of unparalleled” in his extensive Cambridge is approximately 19 local experience. To quote his miles to the west where there are comment made in 2001:- “...The extensive shopping, cultural, decision to build two chimney recreational and schooling stacks separated by an unheated facilities. room instead of the usual back- to-back arrangement was • The pretty village of financially extravagant perhaps Wickhambrook is close by prompted by the urgent need to offering local amenities - a village separate the occupants of the shop/post office and doctor’s hall from those of the principal surgery. parlour...” • Local schools include Of rendered elevations beneath a Wickhambrook Primary School, mix of thatched and tiled roof’s, Barnardiston Hall Preparatory the house today provides really School, Fairstead House in comfortable and versatile Newmarket and Culford Senior accommodation over two floors and Preparatory School near with many of the classic features Bury St. -

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History

SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY • BUSINESS AND ACTIVITIES 1977 151 OFFICERS AND COUNCIL MEMBERS OF THE SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY ,1977 Patron COMMANDER THE EARL OF STRADBROKE, R.N. (Retd.). Lord Lieutenantof Suffolk President DR J. M. BLATCHLY, M.A., F.S.A. Vice-Presidents THE EARL OF CRANBROOK, C.B.E., F.L.S. LESLIE DOW, F.S.A. M. F. B. FITCH, D.Litt., F.S.A. NORMAN SMEDLEY, M.A., F.S.A., F.M.A. THE REV. J. S. BOYS SMITH, M.A., tioN.LL.D. ElectedMembersof theCouncil W. G. ARNOTT L. S. HARLEY, B.SC., F.S.A. MISS PATRICIA BUTLER, M.A., F.S.A., F.M.A. MISS ELIZABETH OWLES, B.A., F.S.A. MRS M. E. CLEGG, B.A., F.R.HIST.S. D. G. PENROSE, B.A. MRS S. J. COLMAN, B.SC. (ECON.) J. SALMON, B.A., F.S.A. MISS GWENYTH DYKE W. R. SERJEANT, B.A., F.R.HIST.S. D. P. DYMOND, M.A., F.S.A. S. E. WEST, M.A., A.M.A., F.S.A. Hon Secretaries GENERAL J. J. WYMER, P.S.A., I 7 Duke Street, Bildeston. ASSISTANT GENERAL P. NORTHEAST, Green Pightle, Hightown Green, Rattlesden FINANCIAL F. S. CHENEY, 28 Fairfield Avenue, Felixstowe EXCURSIONS NORMAN SCARFE, M.A., F.S.A., Shingle Street, Woodbridge. MEMBERSHIP D. THOMPSON, I Petticoat Lane, Bury St Edmunds. Hon. Editor VICTOR GRAY, M.A., Essex Record Office, County Hall, Chelmsford, Essex. Hon. NewsletterEditor E. A. MARTIN, B.A., Firs Farmhouse, Fishponds Way, Haughley, Stowmarket Hon. -

Situation of Polling Stations West Suffolk

Situation of Polling Stations Blackbourn Electoral division Election date: Thursday 6 May 2021 Hours of Poll: 7am to 10pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Situation of Polling Station Station Ranges of electoral register Number numbers of persons entitled to vote thereat Tithe Barn (Bardwell), Up Street, Bardwell 83 W-BDW-1 to W-BDW-662 Barningham Village Hall, Sandy Lane, Barningham 84 W-BGM-1 to W-BGM-808 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-BHM-1 to W-BHM-471 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-EUS-1 to W-EUS-94 Coney Weston Village Hall, The Street, Coney 86 W-CWE-1 to W-CWE-304 Weston St Peter`s Church (Fakenham Magna), Thetford 87 W-FMA-1 to W-FMA-135 Road, Fakenham Magna, Thetford Hepworth Community Pavilion, Recreation Ground, 88 W-HEP-1 to W-HEP-446 Church Lane Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-HN-VL-1 to W-HN-VL-270 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-SAP-1 to W-SAP-163 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-HOP-1 to W-HOP-500 Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-KNE-1 to W-KNE-19 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXT-1 to W-IXT-53 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXW-1 to W-IXW-1674 Market Weston Village Hall, Church Road, Market 92 W-MWE-1 to W-MWE-207 Weston Stanton Community Village Hall, Old Bury Road, 93 W-STN-1 to W-STN-2228 Stanton Thelnetham Village Hall, School Lane, Thelnetham 94 W-THE-1 to W-THE-224 Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of a Police and Crime Commissioner for Suffolk and where applicable and contested, District Council elections, Parish and Town Council elections and Neighbourhood Planning Referendums. -

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 19/06/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/20/0847/AG1 Determination in Respect of Permitted Leys Farm DECISION: Agricultural Development - Access for farm Church Lane Not Required machinery to arable land Barnardiston DECISION TYPE: CB9 7TL Delegated APPLICANT: Mr Andrew Crossley - Thurlow ISSUED DATED: Estate Farms Ltd 15 Jun 2020 WARD: Clare, Hundon And Kedington PARISH: Barnardiston DC/20/0528/FUL Planning Application - Partial change of use Church Farm, Unit 9 DECISION: of storage and distribution warehouse Church Road Approve Application (Class B8) to include office use (Class B1) Barrow DECISION TYPE: IP29 5AX Delegated APPLICANT: Mr Gordon - Kiezebrink UK ISSUED DATED: Limited 17 Jun 2020 WARD: Barrow AGENT: Mr Samuel Stonehouse - Evolution PARISH: Barrow Cum Town Planning Ltd Denham DC/20/0405/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) Larkside DECISION: single storey side extensions and rear 12 Worlington Road Approve Application extensions (following demolition of existing Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: conservatory) (ii) single storey front IP28 7DY Delegated extension (iii) raising roof structure to ISSUED DATED: create habitable living space (iv) 18 Jun 2020 demolition of existing garage WARD: Manor PARISH: Barton Mills APPLICANT: Mr Hewitt AGENT: Mr Craig Farrow - TAB Architecture Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/20/0653/HH Householder Planning -

Prominent Elizabethans. P.1: Church; P.2: Law Officers

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

Church Plate in Suffolk. Deaneryof

( 292 ) •CHURCH PLATE IN SUFFOLK. DEANERYOF THURLOW. This Deanery possesses kveral pieces of Communion Plate of an interesting Character. The chalice in use at Higham Green , is .no .doubt partly, if not entirely,. -of medieval date, although of foreign. make. , It is a simple and beautiful ..'specimen. Another at Lydgate, probably German., ,is very good, but of later character. ,There are 'Elizabethan pieces,of the usual shape, at Cowlinge,Gazeley, and Great Thurlow. The Dalhany plate is a.-fine and interesting set, with the cipher and mitre of.the Wellknown Bishop. Simon .Patrick.'. The only: armOrial :plate..is at Ousden,.where are four „handsome,pieces with the:arms of, the •Moseley fathily, of the 'early' part ..of the eighteenth century, but slightly varying 'in date,. The kind -Welcome and ready asistance gi)ien }.)ythe clergy in each parish is gratefully acknowledged'. MANNINt-;F:S.A. Di„§sRectory, Norfolk.' BRADLEY'GREAT: S: MARy.• CUPS: (1). :plain boWl, diameter 31. inches;. height 7 inches. Inscription on the fobt.:Grate!.Bradlek* • Marks : leopard's head crowned,; makei.'s mark C 0G in trefoil; Small Roman h for 1743 ; lion passant. plain bowl. Height 71 inches; diameter 3/ inches. Marks.: leopard's head crowned; maker's mark ; Roman capital 0 for 1809 ; lion passant; head of Georgein. plated. Height .7/ inches ; diameter of bowl, 3/ inches. PATENS : (1) diameter 7* inches. Marks : leopard's head crowned; maker's mark A.B. in shaped shield ; black letter small g for 1684 ; lion passant. (2) flat ; a cross on the rim. Diameter 4i inches. Marks : leopard's head uncrowned; maker's mark J. -

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense Within West Suffolk District

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense within West Suffolk District Hint: To find a parish or street use Ctrl F The information in this “List of Streets” was derived from Suffolk County Council’s digital Local Street Gazetteer. While considerable care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the Street Gazetteer, Suffolk County Council cannot accept any responsibility for errors, omissions, or positional accuracy. There are no warranties, expressed or implied, including the warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose, accompanying this product. However, notification of any errors will be appreciated. Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Ampton Carriageway Folly Lane 1.55 37403388 A134 Ingham Road 0.82 37403542 C650 New Road 2.17 37400982 C650, U6307 Public footpath Ampton Footpath 001 0.60 37490130 Y108/001/0 Bardwell Page 1 of 148 01/03/2021 Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Carriageway Bowbeck 2.06 37403082 C643 Church Road 0.31 37400567 U6429 Daveys Lane 0.74 37400639 U6439 Ixworth Road 0.84 37403548 C642 Ixworth Thorpe Road 1.04 37403552 U6428 Knox Lane 0.61 37400871 U6441 Lammas Close 0.18 37400877 U6430 Low Street 0.81 37400911 C642 Quaker Lane 0.65 37401072 C642 Road From A1088 To B1111 0.72 37401684 C643 Road From C642 To C643 0.86 37401745 U6424 Road From C644 And C642 To A1088 2.29 37401749 C642 School Lane 0.38 37401118 U6428 Spring Road 1.40 37401160 C642 Stanton Road 0.63 37401182 U6432 The Croft 0.42 37401222 U6430 The Green 0.34 37403966 U6439 Up Street -

CHURCHES in the Stour Valley

CHURCHES in The Stour Valley Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) St Mary the Virgin, Cavendish St Lawrence, Stour Valley and surrounding Wool Towns Peacocks Road, The Green, St Gregory and St George, Little Waldingfield St Peter and St Paul, Clare Cavendish CO10 8AZ Church Road, Little Waldingfield CO10 0SP Stour Valley Path High Street, Clare CO10 8NY Set beside a thatched Alms House, this Pentlow Late medieval church of Perpendicular style, attractive church includes an elaborate Pentlow Lane, Pentlow CO10 7SP with beautiful carvings, stained glass and Wool Towns A very large, beautiful ‘wool church’ with the heaviest ring of eight bells in Suffolk. medieval ‘reredos’. On the river itself, one of only three round Tudor red brick porch. www.achurchnearyou.com/church/2115 www.cavendishvillage.uk/facilities/churches towered churches in the Valley. www.boxriverbenefice.com - Highlights www.stourvalley.org.uk www.achurchnearyou.com/church/2117 www.achurchnearyou.com/church/6520 www.achurchnearyou.com/church/2194 Crown copyright. To Bury St John the Baptist, Boxted St Edmunds Stoke by Clare To Newmarket 16 The Street, Stoke by Clare CO10 8HR 8 St Matthew, Leavenheath St Mary, Polstead All rights reserved. © Suffolk County Council. Licence LA100023395 See a castellated tower, one of the Nayland Road, Leavenheath CO6 4PT Polstead CO6 5BS smallest pulpits in England, and Small, red brick, Victorian church with A unique church with the only elaborate interior decor. LAVENHAM a unique set of First World War white original medieval stone spire www.achurchnearyou.com/church/2118 Great Glemsford grave crosses. remaining in the Stour Valley.