Craving and Opioid Use Disorder a Scoping Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

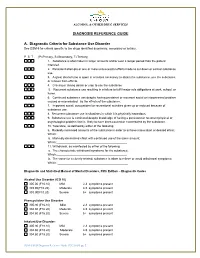

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Neurobiology of Craving: Current Findings and New Directions

Current Addiction Reports https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0202-2 ADOLESCENT/YOUNG ADULT ADDICTION (T CHUNG, SECTION EDITOR) Neurobiology of Craving: Current Findings and New Directions Lara A. Ray1,2 & Daniel J. O. Roche2 # Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Purpose of the Review This review seeks to provide an update on the current literature on craving and its underlying neurobi- ology, as it pertains to alcohol and drug addiction. Recent Findings Studies on craving neurobiology suggest that the brain networks activated by conditioned cues in alcohol- and drug-dependent populations extend far beyond the traditional mesolimbic dopamine system and suggest that the early neurobiolog- ical theories of addiction, which heavily relied on dopamine release into the nucleus accumbens as the primary mechanism driving cue-induced craving and drug-seeking behavior, are incomplete. Ongoing studies will advance our understanding of the neurobio- logical underpinnings of addiction and drug craving by identifying novel brain regions associated with responses to conditioned cues that may be specific to humans, or at least primates, due to these brain areas’ involvement in higher cognitive processes. Summary This review highlights recent advances and future directions in leveraging the neurobiology of craving as a transla- tional phenotype for understanding addiction etiology and informing treatment development. The complexity of craving and its underlying neurocircuitry is evident and divergent methods of eliciting craving (i.e., cues, stress, and alcohol administration) may produce divergent findings. Keywords Craving . Addiction . Neurobiology . fMRI . Cue reactivity . Alcohol . Drug Introduction relative risk of all other diagnostic criteria for alcoholism [4]. -

MARIJUANA and SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a Historical Perspective and DSM-5 Overview

MARIJUANA AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a historical perspective and DSM-5 overview Introduction Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the Western world and the third most commonly used recreational drug after alcohol and tobacco. According to the World Health Organization, it also is the illicit substance most widely cultivated, trafficked, and used. Although the long-term clinical outcome of marijuana use disorder may be less severe than other commonly used substances, it is by no means a "safe" drug. Sustained marijuana use can have negative impacts on the brain as well as the body. Studies have indicated a link between regular marijuana use and schizophrenia as well as a demonstrated relationship between marijuana use and a higher incidence of lung cancer. Although there are no pharmacological treatments available with a proven impact on marijuana use disorder, there are several types of behavior therapy that may be effective in treating this disorder. Worldwide Use Of Marijuana For a number of years, the United Nations has been compiling annual surveys of worldwide drug use, including cannabis. Reflecting the difficulties and uncertainties associated with developing estimates of the number of people who use drugs (such as the quality of the data gathered and the methodologies used to sample populations), the latest United Nations estimates are presented in ranges, reflecting the lower and upper estimates indicated through the array of surveys ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 1 available. In their 2012 report (covering 2010), the United Nations estimated that between 119.4 and 224.5 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 had used cannabis in the past year, representing between 2.6% and 5.0% of the world’s population.22 In 2014, approximately 22.2 million people ages 12 and up reported using marijuana during the past month. -

Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving: an Investigation Examining Cognitive and Academic Impairment Daniel Vigil

Ursidae: The Undergraduate Research Journal at the University of Northern Colorado Volume 4 Article 2 Number 2 McNair Special Issue January 2014 Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving: An Investigation Examining Cognitive and Academic Impairment Daniel Vigil Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/urj Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Vigil, Daniel (2014) "Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving: An Investigation Examining Cognitive and Academic Impairment," Ursidae: The Undergraduate Research Journal at the University of Northern Colorado: Vol. 4 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/urj/vol4/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursidae: The ndeU rgraduate Research Journal at the University of Northern Colorado by an authorized editor of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vigil: Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving Cue Reactivity of Marijuana Craving: An Investigation Examining Cognitive and Academic Impairment Daniel Vigil, Psychology Mentor: Kristina Phillips, Ph.D., School of Psychological Sciences Abstract: Craving contributes to the development of substance disorders and is a significant factor leading to relapse. With the legalization of medicinal marijuana and retail marijuana in some states, understanding the effects of craving is essential. I designed an experiment to determine whether marijuana craving leads to cognitive and academic impairment among college students. I hypothesized that participants provided with a marijuana cue would demonstrate greater problems with working memory and reading comprehension than those assigned to a neutral cue control group. -

Components Influencing Craving in Substance Use Disorders

COMPONENTS INFLUENCING CRAVING IN SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS By John Winters Baley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Psychology By John Winters Baley Director: Dr. Kia Karin Asberg Associate Professor of Psychology Psychology Department Committee Members: Dr. David Mark McCord, Psychology Dr. Norman G. Hoffman, Psycholoy June 2007 ©2014 John Winters Baley 2 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I would like pause here and issue a hearty thank you to each of my committee members. Without their support and encouragement this document would not exist. Dr. Kia Asberg I am indebted to you for your patience and guidance. Dr. Norman Hoffmann I would have been lost without your vision and direction. Dr. David McCord your carefully considered words shaped this project in subtle ways that improved it dramatically. Thank you all. For everything. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables 4 Abstract 5 Chapter 1. Introduction 6 Chapter 2. Literature Review 10 Substance Use Disorder 10 Treatment for SUD 10 Substance Craving 11 The Importance of Craving 11 Measures and Models of Craving 13 Associations Between Craving and SUD 14 The role of craving in SUD 14 Craving and relapse potential 16 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms 17 DARNU’s Relationship with Truama, Craving, and SUD 21 Statement of the Problem 25 Hypotheses 26 Chapter 3. Methods 27 Participants 27 Measures 28 Procedure 30 Analyses 30 Chapter 4. Results 32 Chapter 5. Discussion 35 References 39 Appendix 1: Initial CORI Psychometrics and Individual Scales 49 Appendix 2: Penn Alcohol/Drug Craving Scale (PADC) 56 Appendix 3: ANOVA for Between Group Differences 58 LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. -

N-Acetylcysteine: a Potential Treatment for Substance Use Disorders This OTC Antioxidant May Benefit Adults Who Use Cocaine and Adolescents Who Use Marijuana

N-acetylcysteine: A potential treatment for substance use disorders This OTC antioxidant may benefit adults who use cocaine and adolescents who use marijuana Rachel L. Tomko, PhD harmacologic treatment options for many substance use disor- Research Assistant Professor Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences ders (SUDs) are limited. This is especially true for cocaine use Jennifer L. Jones, MD disorder and cannabis use disorder, for which there are no FDA- Resident Physician approved medications. FDA-approved medications for other SUDs often Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences take the form of replacement or agonist therapies (eg, nicotine replace- and Internal Medicine ment therapy) that substitute the effects of the substance to aid in ces- Amanda K. Gilmore, PhD sation. Other pharmacotherapies treat symptoms of withdrawal, reduce Research Assistant Professor College of Nursing and Department of Psychiatry craving, or provide aversive counter-conditioning if the patient consumes and Behavioral Sciences the substance while on the medication (eg, disulfiram). Kathleen T. Brady, MD, PhD The over-the-counter (OTC) antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) may Distinguished University Professor be a potential treatment for SUDs. Although NAC is not approved by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences FDA for treating SUDs, its proposed mechanism of action differs from Sudie E. Back, PhD that of current FDA-approved medications for SUDs. NAC’s potential for Professor Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences broad applicability, favorable adverse-effect profile, accessibility, and low Kevin M. Gray, MD cost make it an intriguing option for patients with multiple comorbidi- Professor ties, and potentially for individuals with polysubstance use. -

Neural Mechanisms Underlying Craving and the Regulation of Craving Hedy Kober and Maggie Mae Mell

9 Neural Mechanisms Underlying Craving and the Regulation of Craving Hedy Kober and Maggie Mae Mell Introduction Craving has long been considered a core feature of addiction (World Health Organization, 1955; O’Brien, Childress, Ehrman, & Robbins, 1998; Volkow et al., 2006; Sinha & Li, 2007; Kavanagh & Connor, 2012). Consistently, over the last two decades, a wealth of research has directly linked drug craving with drug taking and relapse (e.g., Heinz et al., 2005; Crits‐Christoph et al., 2007; Allen, Bade, Hatsukami, & Center, 2008; Shiffman et al., 2013; Kober, 2014 for review). On the basis of the accumulated evidence, the American Psychiatric Association recently added craving – defined as “a strong desire for drugs” – as a diagnostic criterion for substance‐related and addictive disorders in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM‐5) (APA, 2013). Also defined as a “conscious, reportable urge” (Preston et al., 2009), craving can be experienced for a range of appetitive stimuli, including drugs – but also food, sex, and money. As such, craving is a very common phenomenon. In fact 94% of males and 100% of females report having expe- rienced craving for a specific food at some point in their lives (Osman & Sobal, 2006).1 Nevertheless, in the context of substance use disorders, a failure to regulate craving can lead to dire outcomes, such as harmful drug use. In the next sections we will review craving’s central causal role in drug use and relapse and will consider the brain regions that underlie craving. Then we will review the role of the regulation of craving in reducing craving and in treatment for addiction, as well as the neural mechanisms that give rise to this ability. -

UNDERSTANDING and TREATING CANNABINOID ADDICTION Cardwell C

UNDERSTANDING AND TREATING CANNABINOID ADDICTION Cardwell C. Nuckols, PhD [email protected] www.cnuckols.com UNDERSTANDING AND TREATING CANNABINOID ADDICTION • CANNABIS AND CANNABINOIDS • CANNABINOID EFFECTS AND TOXICITY • MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES • ASSESSMENT AND DSM-5 • CRAVING • TREATMENT-PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY AND PSYCHOTHERAPY MARIJUANA PLANT MAIN COLA HONEY OIL HONEY OIL • Known as ―honey oil,‖ Butane hash oil (BHO) ―hash oil,‖ ―dabs,‖ ―earwax,‖ ―butter‖ or ―shatter,‖ among other names, homemade marijuana concentrates have caught on quickly because of the popularity and availability of e-cigarettes and vaporizer pens, which offer an easy, discreet way to use the drug. HONEY OIL • Hash oil is one of the most potent forms of (medical) marijuana. The oil is highly concentrated, with THC levels between 40% and 90%. Hash oil is a resinous matrix of cannabinoids produced by a solvent extraction of marijuana. The oil varies in appearance from a crystal-clear, glossy amber to gold resin, and is usually very thick and vicious. The best quality is transparent and relatively free of impurities. VAPING AND DABBING • Now marijuana is smoked through a vaporizer (vape) pen that gives users a faster and stronger high. These new forms of marijuana are available as oils, waxes, and hard crystal wafers called shatter • New Forms of Marijuana: Oil: Refined version of marijuana resembling honey. It is created using liquids and gases such as water, butane, alcohol and carbon dioxide. THC: 60-80% Shatter: Created using the same methods as oil repeated multiple times. The extra filtration and purification process increase the potency. THC: 75-90% Wax: Created by a process similar to that of oil. -

Craving and Depression in Opiate Dependent Mentally Ill African

Research Article iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry 2017 http://www.imedpub.com/ Vol.3 No.2:11 ISSN 2471-9854 DOI: 10.21767/2471-9854.100042 Craving and Depression in Opiate Dependent Mentally Ill African Americans Receiving Buprenorphine/Naloxone and Group CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) Tanya Alim1*, Suneeta Kumari1, Leslie Adams2, Didier Anton Saint-Cyr1, Steve Tulin1, Elizabeth Carpenter-Song3, Maria Hipolito1, Loretta Peterson1 and William B Lawson4 1Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, College of Medicine, Howard University, USA 2Health Behavior Doctoral Student, University of North Carolina, United States 3Assistant Professor of Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center (PRC), Geisel School of Medicine, United States 4Associate Dean for Health Disparities, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas, Texas Corresponding author: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, College of Medicine, Howard University, Washington, D.C., USA, Tel: 202-865-3796; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: June 15, 2017; Accepted date: July 11, 2017; Published date: July 18, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Alim T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Alim T, Kumari S, Adams L, Saint-Cyr A, Tulin S, et al. Craving and Depression in Opiate Dependent Mentally Ill African Americans Receiving Buprenorphine/Naloxone -

N-Acetylcysteine in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders

DOI: 10.14744/DAJPNS.2019.00055 Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2020;33:1-7 EDITORIAL N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of substance use disorders Cuneyt Evren1 , Izgi Alniak1 1Bakirkoy Training and Research Hospital for Psychiatry Neurology and Neurosurgery, Research, Treatment and Training Center for Alcohol and Substance Dependence (AMATEM), Istanbul - Turkey ABSTRACT N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an agent best known for its clinical efficacy in bronchopulmonary disorders due to its mucolytic properties, and in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Given the strong clinical evidence from animal studies of its critical role in regulating glutamatergic receptors, NAC has also been the subject of research related to several psychiatric disorders as a promising treatment approach. This editorial is a brief discussion of the characteristics of NAC and its place in substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an N-acetylated derivative into the extracellular environment, thus raising of the naturally occurring amino acid cysteine (1). NAC extracellular glutamate levels in many tissues including is a white, crystalline compound; the molecular formula the brain (1,4,6). is C5H9NO3S (2). As a drug, it has been available for The clinical efficacy of NAC as a mucolytic agent for several years in intravenous, oral, and nebulizer forms bronchopulmonary disorders and in the treatment of (2,3). Inside several organs (including the brain), free acetaminophen overdose has been proven worldwide cysteine is formed by deacetylation of NAC. Two cysteine (6). On the other hand, an increasing number of clinical molecules are then homodimerized via a disulfide bond, studies indicate the efficacy of NAC in various forming cystine. -

Impact of the Dsm-Iv to Dsm-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health

IMPACT OF THE DSM-IV TO DSM-5 CHANGES ON THE NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH DISCLAIMER SAMHSA provides links to other Internet sites as a service to its users and is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites. SAMHSA, its employees, and contractors do not endorse, warrant, or guarantee the products, services, or information described or offered at these other Internet sites. Any reference to a commercial product, process, or service is not an endorsement or recommendation by SAMHSA, its employees, or contractors. For documents available from this server, the U.S. Government does not warrant or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Rockville, Maryland 20857 June 2016 This page intentionally left blank IMPACT OF THE DSM-IV TO DSM-5 CHANGES ON THE NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Contract No. HHSS283201000003C RTI Project No. 0212800.001.108.006.026 RTI Authors: RTI Project Director: Cristie Glasheen David Hunter Kathryn Batts Rhonda Karg SAMHSA Project Officer: Peter Tice SAMHSA Authors: Jonaki Bose Sarra Hedden Kathryn Piscopo For questions about this report, please e-mail [email protected]. Prepared for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, Maryland Prepared by RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina June 2016 Recommended Citation: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. -

Regulation of Craving and Negative Emotion in Alcohol Use Disorder

Biological Psychiatry: Archival Report CNNI Regulation of Craving and Negative Emotion in Alcohol Use Disorder Shosuke Suzuki, Maggie Mae Mell, Stephanie S. O’Malley, John H. Krystal, Alan Anticevic, and Hedy Kober ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a chronic, relapsing condition with poor treatment outcomes. Both alcohol craving and negative affect increase alcohol drinking, and—in healthy adults—can be attenuated using cognitive strategies, which rely on the prefrontal cortex (PFC). However, AUD is associated with cognitive impairments and PFC disruptions. Thus, we tested whether individuals with AUD can successfully recruit the PFC to effectively regulate craving and negative emotions, whether neural mechanisms are shared between the two types of regulation, and whether individual differences influence regulation success. METHODS: During functional magnetic resonance imaging, participants with AUD completed the regulation of craving task (n = 17) that compares a cue-induced craving condition with an instructed regulation condition. They also completed the emotion regulation task (n = 15) that compares a negative affect condition with an instructed regulation condition. Regulation strategies were drawn from cognitive behavioral therapy treatments for AUD. Self-reported craving and negative affect were collected on each trial. RESULTS: Individuals with AUD effectively regulated their craving and negative affect when instructed to do so using cognitive behavioral therapy–based strategies. Regulation was associated with recruitment of both common and distinct PFC regions across tasks, as well as with reduced activity in regions associated with craving and negative affect (e.g., ventral striatum, amygdala). Effective regulation of craving was associated with negative alcohol expectancies. CONCLUSIONS: Both common and distinct regulatory systems underlie regulation of craving and negative emotions in AUD, with notable individual differences.