Revealing Oil Spots 13Nov12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karbury's Auction House

Karbury's Auction House Antiques Estates & Collection Sale Saturday - September 8, 2018 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 307: A Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddhist Figure USD 300 - 500 308: A Set of Four Bronze Cups USD 200 - 300 309: A Song Style Jizhou Tortoiseshell-Glazed Tea Bowl USD 1,000 - 2,000 310: A Bronze Snake Sculpture USD 100 - 200 311: A Wood Pillow with Bone Inlaid USD 100 - 200 312: A Carved Ink Stone USD 200 - 300 313: A Stone Carved Head of Buddha USD 100 - 200 314: A Doucai Chicken Cup with Yongzheng Mark USD 500 - 700 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 1 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 315: A Jian Ware Tea Bowl in Silver Hare Fur Streak USD 800 - 1,500 316: A Celadon Glazed Double Gourd Vase USD 400 - 600 317: Three Porcelain Dog Figurines USD 200 - 400 318: A Jun ware flower Pot USD 1,500 - 2,000 319: A Pair of Famille Rose Jars with Cover USD 800 - 1,200 320: A Blanc-De-Chine Figure of Seated Guanyin USD 1,500 - 2,000 321: A Pair of Vintage Porcelain Lamps USD 200 - 300 322: A Chicken Head Spout Ewer USD 800 - 1,200 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 2 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 323: Two sancai figures and a ceramic cat-motif pillow USD 200 - 300 324: A Teadust Glazed Vase with Qianlong Mark USD 500 - 800 325: A Rosewood Tabletop Curio Display Stand USD 300 - 500 326: A Blue and White Celadon Glazed Vase USD 300 - 500 327: A Wucai Dragon Jar with Cover USD 300 - 500 328: A Green and Aubergine-Enameled Yellow-Ground Vase USD 200 - 300 329: A Celadon Square Sectioned Dragon Vase USD 200 - 300 -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49995-8 — the City of Blue and White Anne Gerritsen Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49995-8 — The City of Blue and White Anne Gerritsen Index More Information 321 Index Note: Page numbers in bold refer to fi gures, and those in italics refer to maps. Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), trade in, 1 – 2 introduction of, 15 Abu- Lughod, Janet, 44 – 46 , 45 , 47 , 55 Jingdezhen emergence of, 61 , 68 Ackerman- Lieberman, Phillip, 59 Jingdezhen global production of, 5 Africa, porcelain trade in, 59 in Joseon Korea, 125 , 125 , 126 animal patterns, 198 Kessler on dating of, 64 in Jizhou ceramics, 82 – 83 , 93 – 94 , 95 Linjiang kilns and, 102 – 103 see also deer ; dragon in ritual texts, 127 – 128 archaeologists, on porcelains, 6 , 117 in shard market, 3 – 5 , 16 , 1 7 archaeology, 6 , 12 – 13 , 34 , 52 , 82 – 83 , 106 underglaze painting of, 67 Cizhou ware ceramics, 32 – 33 Yu a n d y n a s t y a n d , 6 6 Ding ware ceramics, 24 , 32 – 33 bluish- white glaze, of qingbai ceramics, 40 Fengzhuang storehouse, 21 – 22 ‘Book of Ceramics’, see Taoshu hoards, 72 bottle Hutian kilns, 49 , 264n54 gourd- shaped, 196 – 197 , 196 , 198 , 214 Jizhou ware, 93 , 97 in shard market, 3 – 5 Linjiang kiln site, 102 – 103 tall- necked porcelain, 198 , 199 , maritime, 12 – 13 , 52 – 55 , 127 – 128 204 – 205 , 215 qingbai ceramics, 52 bowl, 172 shard market, 1 , 16 , 1 7 fi sh, 228 – 230 S i n a n s h i p w r e c k , 5 2 – 5 5 glaze patterns for, 35 – 36 Western Xia dynasty, 51 Jizhou ceramics dated, 95 , 96 , 97 Yonghe kilns, 76 , 77 w i t h luanbai glaze, 47 – 48 , 48 Ardabil collection, 205 in shard market, 3 – 5 art history, of porcelains, 6 see also tea bowls ‘Assorted Jottings of Shi Yushan’ Shi Yushan Brandt, George, 64 bieji (Shi Runzhang), 101 Brankston, A. -

List 3. Headings That Need to Be Changed from the Machine- Converted Form

LIST 3. HEADINGS THAT NEED TO BE CHANGED FROM THE MACHINE- CONVERTED FORM The data dictionary for the machine conversion of subject headings was prepared in summer 2000 based on the systematic romanization of Wade-Giles terms in existing subject headings identified as eligible for conversion before detailed examination of the headings could take place. When investigation of each heading was subsequently undertaken, it was discovered that some headings needed to be revised to forms that differed from the forms that had been given in the data dictionary. This occurred most frequently when older headings no longer conformed to current policy, or in the case of geographic headings, when conflicts were discovered using current geographic reference sources, for example, the listing of more than one river or mountain by the same name in China. Approximately 14% of the subject headings in the pinyin conversion project were revised differently than their machine- converted forms. To aid in bibliographic file maintenance, the following list of those headings is provided. In subject authority records for the revised headings, Used For references (4XX) coded Anne@ in the $w control subfield for earlier form of heading have been supplied for the data dictionary forms as well as the original forms of the headings. For example, when you see: Chien yao ware/ converted to Jian yao ware/ needs to be manually changed to Jian ware It means: The subject heading Chien yao ware was converted to Jian yao ware by the conversion program; however, that heading now -

Tianmu Bowls

GLOBAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 May 2018 Tianmu天目 Bowls GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 76 / May 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Cloud祥雲寺 Temple This month, we are excited to dive into the world of tea bowls, exploring how to choose bowls for tea and the history of China’s most Love is famous bowls, called “tianmu.” And we have a great green tea to drink as we discuss the his- changing the world tory, production and lore of tianmu as well as some modern artists making tianmu bowls. bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 13 The Glory of Tianmu By Wang Duozhi (王多智) 25 Tianmu Kilns in 03 Fujian By Li Jian’an (栗建安) 42 Yao Bian Tianmu 13 By Lin Jinzhong (林錦鐘) 45 Shipwrecked Tianmu By Huang Hanzhang (無黃漢彰) 33 Traditions傳統文章 53 03 Tea of the Month “Cloud Temple,” Fresh Spring Green Tea Mingjian, Nantou, Taiwan 21 Cha Dao How to Hold the Bowl By Jing Ren (淨仁) Teaware Artisans p. 33 Lin Jinzhong, by Wu De (無的) p. 53 Wang Xi Rui, by Wu De (無的) 祥 © 2018 by Global Tea Hut 59 Special Offer All rights reserved. Wang Xi Rui Tianmu Bowls 雲 No part of this publication may be re- 寺 produced, stored in a retrieval system 61 TeaWayfarer or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, pho- Erin Farb, USA tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. n May, TaiwanFrom really warms up and we startthe turn- cover teaware in atEditor least one issue, which we are presenting ing more to lighter teas like green teas, white teas in this very issue. -

ASIAN ART Monday 8 and Tuesday 9 May 2017 Knightsbridge, London

ASIAN ART Monday 8 and Tuesday 9 May 2017 Knightsbridge, London INTERNATIONAL CHINESE CERAMICS AND WORKS OF ART TEAM Colin Sheaf Dessa Goddard Asaph Hyman ASIA AND AUSTRALIA Xibo Wang Gigi Yu John Chong Edward Wilkinson* Yvett Klein Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong Sydney EUROPE Benedetta Mottino Sing Yan Choy Edward Luper Rachel Hyman Rosangela Assennato Ben Law Smith Ian Glennie Asha Edwards London, London, London, London, London, London, Edinburgh Edinburgh New Bond Street New Bond Street New Bond Street Knightsbridge Knightsbridge Knightsbridge USA Bruce MacLaren Nicholas Rice Ming Hua Harold Yeo Mark Rasmussen* Doris Jin Huang* New York New York New York New York New York New York Henry Kleinhenz Daniel Herskee Ling Shang San Francisco San Francisco San Francisco ASIA REPRESENTATIVES Summer Fang Bernadette Rankine Taipei Singapore Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Harvey Cammell Deputy Chairman, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, India Phillips, Matthew Girling CEO, Lucinda Bredin, Simon Cottle, Andrew Currie, Peter Rees, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Paul Davidson, Jean Ghika, Veronique Scorer, James Stratton, Ralph Taylor, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Rupert Banner, Geoffrey Davies, Charles Graham-Campbell, Matthew Haley, Charlie Thomas, David Williams, Jonathan Fairhurst, Asaph Hyman, James Knight, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, David Johnson, Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. -

Eiseibunkomuseumearlyspring2

The Eisei Bunko Collection Eisei Bunko Museum was established in 1950 by Moritatsu, the 16th head of the Hosokawa family that formerly ruled over the vast Higo-Kumamoto domain and was authorized as a public interest incorporated foundation in December 2009. Moritatsu’s intention was to preserve and carry out research of his own art collection as well as the numerous artworks and historical materials that were handed down through the family for generations. The name “Eisei” is a combination of “Ei” of Eigen-an and “Sei” of Seiryuji (Shoryuji) Castle, both deeply connected to the history of the family. Eigen-an is a sub-temple of the Kyoto Kenninji, where successive generations from Hosokawa Yoriari (1332-91), the founder of the clan and a military commander during the Nanbokucho period, to Mototsune (1482-1554) are buried. Shoryuji Castle was the residence of Hosokawa Fujitaka (Yusai 1534-1610), who is revered as the first generation of the modern line of the Hosokawa family. Eisei Bunko Museum is located in a verdant area of Mejirodai in Bunkyo-ku, where visitors can enjoy the traditional landscape of Musashino. The suburban residence of the Hosokawa family was formerly located in this area, and the museum building had been previously used as “kaseijo” (administrative office) before renovation in the early Showa period. The museum holds nearly 94,000 items of artworks and documents related to the 700 year history of the Hosokawa family and Moritatsu’s private art collection including 8 National Treasures and 32 Important Cultural Properties. The collection consists of various objects such as arms and armor, textiles, paintings, calligraphic works, ceramics, lacquer works, sculptures, historical documents, and modern Japanese paintings, and is highly appreciated as a valuable historical resource worldwide. -

Effect of Phase Separation on the Jian Ware Blue Colored Glaze with Iron

Ceramics International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ceramics International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ceramint Effect of phase separation on the Jian ware blue colored glaze with iron oxide ⁎ Pei Shi, Fen Wang , Jianfeng Zhu, Biao Zhang, Ting Zhao, Yi Wang, Jiahuan Wang School of Materials Science and Engineering, Shaanxi University of Science & Technology, Xi'an 710021, PR China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This study was aimed to explore the effect of phase separation on the Jian ware blue colored glaze with iron Jian ware blue colored glaze oxide. In order to analyze the forming cause of glaze patterns and their coloring mechanism, the phase, mi- Phase separation crostructure and chemical state of the samples were investigated by X-ray diffraction, scanning electron mi- Calcium phosphate croscopy, transmission electron microscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectrum. The results indicated that the Iron oxide addition of calcium phosphate introduced highly-active Ca2+ and P5+ into the glaze. Since Ca2+ with high ionic − potential had a greater ability to appeal O2 than Si4+, the glaze melt was separated into calcium-rich phase and silicon-rich phase. The difference of viscosity caused the non-uniform distribution of quartz and glass phase, and then affected the distribution of iron ions in two phases, which formed glaze patterns. Adding P5+ that had a strong effect of reversed polarization on the Fe-O increased the contents of Fe2+ and Fe3+-O-Fe2+, and thus deepened the blue-green of glaze surface. In addition, it promoted the formation of worm-like phase-separated structures and the existence of structural color. -

The Microstructure of Multicolor Hare's Fur Glaze

Guan et al. Herit Sci (2021) 9:21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00498-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The microstructure of multicolor hare’s fur glaze: the correlation between morphological and compositional characteristics and glaze color Ming Guan1, Baoqiang Kang1, Xiangjun Wei2*, Gen Li1, Cui Jia1, He Li1, Yinzhong Ding1 and Yong Lei1* Abstract The hare’s fur glazed Jian wares characterized by radial fur-like strips, as one of the typical representatives of Chinese ceramics in the 10th-13th century (A.D.), were famous for the aesthetic values in highlighting the color sparkling efects of tea soup, which were one of the indispensable tea wares in tea culture. The fring technology of hare’s fur glaze of Jian wares not only played a crucial role in the development of Chinese ceramic history, but also enlightened the modern imitation technology. The hare’s fur glaze of Jian wares can be further grouped according to the color of strips, of which the yellowish-brown hare’s fur glaze (yellowish-brown matte strips), gold hare’s fur glaze (golden shiny strips) and silver hare’s fur glaze (bright silvery strips) were the most representative types. Epsilon-Fe2O3, a specifc metastable crystal phase, has become a research hotspot as the chromogenic crystals of hare’s fur glaze, however, the comparative analysis focused on the correlation between ε-Fe2O3 and the macroscopic glaze color has been barely reported. In our work, the bright color strips (hare’s fur area) and black strips (black glaze area) of silver, gold and yel- lowish-brown hare’s fur glaze were morphologically and compositionally analyzed by SEM and EDS, respectively. -

Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics

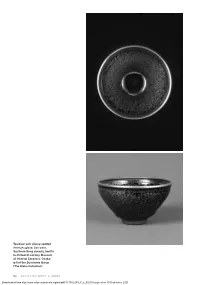

Tea bowl with silvery-spotted tenmoku glaze, Jian ware, Southern Song dynasty, twelfth to thirteenth century. Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka; gift of the Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00230 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00230 by guest on 30 September 2021 Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics JEFFREY MOSER Jeff Wall’s notion of liquid intelligence turns on the dialectic of modernity. On one side of the divide are the dry mechanisms of the camera, which metaphorically and literally express the industrial processes that brought them into being. On the other side is water, which “symbolically represents an archaism in photography, one that is admitted in the process, but also excluded, contained or channelled by its hydraulics.” 1 Wall’s attraction to liquidity is unreservedly nostalgic—it harkens back to archaic processes and what he understands as the ever more remote possibility of fortuity in art-making—and it seeks to find, in the developing fluid of the photograph, a bridge back to the “sense of immersion in the incalculable” that modernity has alienated. 2 For him, liquidity and chance are not simply of the past, they have been made past by the totality of a “modern vision” that inex - orably subjugates them through industry and design. 3 Wall’s formulation implicitly probes the semantic contradiction that imbues Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s famous passage with such force: Where, he inquires, is the liquid elided when “all that is solid melts into air?” 4 The juxtaposition of Wall’s essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence” with his Milk (1984) raises the tension simmering in Wall’s formula. -

A Preliminary Study on the Distribution and Consumption of Ceramics in Hong Kong During the Song-Yuan Period

A PRELIMINARY STUDY ON THE DISTRIBUTION AND CONSUMPTION OF CERAMICS IN HONG KONG DURING THE SONG-YUAN PERIOD Sharon Wai Yee Wong Southeast Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117570 ABSTRACT structure projects affect the potential areas of ancient cul- Preliminary study of unearthed Song-Yuan ceramics (AD tural remains. More and more archaeological investiga- 907-1368) from controlled excavations in Hong Kong tions and excavations have been conducted since the be- suggests that celadon and brown ware are the largest ginning of the enforcement of Environmental Impact As- categories of ceramic types. Bowls, dishes and utilitarian sessment legislation in 1998. Though a large amount of storage vessels such as jars and basins are the major archaeological data from different kinds of sites such as forms of ceramics. Export ceramics from Guangdong tombs and dwelling areas have been accumulated under Province, such as Xicun, Chaozhou and Qishi wares, the enactment of this ordinance, and some important ar- were popular in Hong Kong. Inhabitants also acquired chaeological sites have been recovered in Hong Kong ceramics from other provinces such as Fujian, Jiangxi since the 1930s, the distribution and consumption of ce- and Zhejiang for daily use. Most of the ceramics were ramics have not been systematically analyzed by re- distributed as ordinary commodities in the local market. searchers. A preliminary study of ceramics types and forms controlled excavations will give us a picture of dis- tribution and consumption of ceramics in Hong Kong during the Song-Yuan Period. Historians usually portray Hong Kong as the outer port of DISTRIBUTION OF CERAMICS Guangzhou or as a strategic point on ancient China’s maritime route to Southeast Asia. -

Article 10, Two Great Bequests to the Fitzwilliam Museum

Two Generous Bequests to the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, Oscar Raphael’s Song Ceramics and Sir Reginald Corey’s Imperial Qing Porcelain I last visited the Fitzwilliam Museum in March 2019 and walking through the galleries, I was struck by the variety and quality of the exhibits. On closer examination, it became clear that the museum had benefitted from the bequests of two English collectors who were active in the first half of the 20th Fig 1. Entrance to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. century - Oscar Raphael (1874-1941) and Sir Reginald Radcliffe Cory (1871-1934). Both collectors had split their bequests between the British and Fitzwilliam Museums. In the case of Oscar Raphael, he gave just general guidelines for this and was to let the museums work out the details. Raphael wanted to see that the collections would be placed in the context where they would be most appropriate and give the most pleasure. 1. However, this is where the similarity ends, as Oscar Raphael’s collecting interest were very wide and covered Islamic art, Japanese prints, paintings, netsuke, inro and other lacquer, as well as early and later Chinese jades, archaic bronzes, Song, Yuan and Ming ceramics. Cory’s collecting was much more focused on 18th century imperial Qing enamelled wares, but he did also collect snuff bottles and Japanese inro. His collection amounted to around 1,200 items at his death. The wide and varied collections at the Fitzwilliam are partly due to the director, Sir Sydney Cockerell (1867-1962) who had the practice of bringing in experts and hiring them as honorary keepers. -

Recreating China: an Examination of Design Motifs on Imported Chinese Porcelains and Their Early Japanese Counterparts

RECREATING CHINA: AN EXAMINATION OF DESIGN MOTIFS ON IMPORTED CHINESE PORCELAINS AND THEIR EARLY JAPANESE COUNTERPARTS Nicole Coolidgc Rousmaniere A STRONG UNDERLYING THEME IN EARLY 17TH- Figure /. Closc-up of a Nantban screen, beginning of the 17th century Japanese art is the employment of Chinese century, Suntory Museum, Tokyo. imager)' and symbolism. When these images and symbols are examined they reveal not just a direct Another advantage in using archaeologically recov transference of motifs from China, but also a ered materials, or objects that have been matched in Japanese reconstruction of a specific Chinese the archaeological record, is that their authenticity is aesthetic. Chinese-style imagery appears on all not in question. artistic media in the Japanese early modern period, Before discussing porcelain motifs, it is important from painted screens and architecture to textiles and to make brief mention about terminology. The word ceramics. In this paper, I address primarily motifs ‘China’ is used in two different ways in this paper. executed on early Japanese porcelains compared to The first is the standard use of the word China, as in the motifs found on Chinese porcelains that were Ming period China - or Chinese domestic taste - imported contemporaneously into Japan. The data meaning the taste of the Chinese people. The second for this comparison comes almost exclusively from use of China, and the one that is mostly utilised in recent archaeological investigations correlated with this paper, refers to the Japanese construction of an existing heirloomed collections (dcnseilwi). Because idealised China. This idealised China, while readily of the advanced state of archaeology in Japan with recognisable to the Japanese of the period, had very 20,000 sites excavated on the average each year little to do with the country called China.