A Retrospective Analysis of the Relationship Between Anti-Cyclic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country ABC-Mart 0.01 JAPAN Ebara 0.17 JAPAN JFE Holdings 0.04 JAPAN Acom 0.02 JAPAN Eisai 1.03 JAPAN JGC Corp 0.02 JAPAN Activia Properties 0.01 JAPAN Eneos Holdings 0.05 JAPAN JSR Corp 0.11 JAPAN Advance Residence Investment 0.01 JAPAN Ezaki Glico 0.01 JAPAN JTEKT 0.07 JAPAN Advantest Corp 0.53 JAPAN Fancl Corp 0.03 JAPAN Justsystems 0.01 JAPAN Aeon 0.61 JAPAN Fanuc 0.87 JAPAN Kagome 0.02 JAPAN AEON Financial Service 0.01 JAPAN Fast Retailing 3.13 JAPAN Kajima Corp 0.1 JAPAN Aeon Mall 0.01 JAPAN FP Corporation 0.04 JAPAN Kakaku.com Inc. 0.05 JAPAN AGC 0.06 JAPAN Fuji Electric 0.18 JAPAN Kaken Pharmaceutical 0.01 JAPAN Aica Kogyo 0.07 JAPAN Fuji Oil Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Kamigumi 0.01 JAPAN Ain Pharmaciez <0.005 JAPAN FUJIFILM Holdings 1.05 JAPAN Kaneka Corp 0.01 JAPAN Air Water 0.01 JAPAN Fujitsu 2.04 JAPAN Kansai Paint 0.05 JAPAN Aisin Seiki Co 0.31 JAPAN Fujitsu General 0.01 JAPAN Kao 1.38 JAPAN Ajinomoto Co 0.27 JAPAN Fukuoka Financial Group 0.01 JAPAN KDDI Corp 2.22 JAPAN Alfresa Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Fukuyama Transporting 0.01 JAPAN Keihan Holdings 0.02 JAPAN Alps Alpine 0.04 JAPAN Furukawa Electric 0.03 JAPAN Keikyu Corporation 0.02 JAPAN Amada 0.01 JAPAN Fuyo General Lease 0.08 JAPAN Keio Corp 0.04 JAPAN Amano Corp 0.01 JAPAN GLP J-REIT 0.02 JAPAN Keisei Electric Railway 0.03 JAPAN ANA Holdings 0.02 JAPAN GMO Internet 0.01 JAPAN Kenedix Office Investment Corporation 0.01 JAPAN Anritsu 0.15 JAPAN GMO Payment Gateway 0.01 JAPAN KEWPIE Corporation 0.03 JAPAN Aozora Bank 0.02 JAPAN Goldwin 0.01 JAPAN Keyence Corp 0.42 JAPAN As One 0.01 JAPAN GS Yuasa Corp 0.03 JAPAN Kikkoman 0.25 JAPAN Asahi Group Holdings 0.5 JAPAN GungHo Online Entertainment 0.01 JAPAN Kinden <0.005 JAPAN Asahi Intecc 0.01 JAPAN Gunma Bank 0.01 JAPAN Kintetsu 0.03 JAPAN Asahi Kasei Corporation 0.26 JAPAN H.U. -

【Research Report】The GR Scores 2018

Nikko Research Review Research Report Aug. 2019 The GR Scores 2018 Institute of Social System Research Megumi Terayama Yasuyuki Sugiura Abstract Nikko Research Center, Inc. has developed the Governance Research Scores (GR scores), which evaluate the strength of corporate governance in Japanese companies. We list the GR Scores of 100 Is major domestic companies by benchmarking their practices against Japan’s Corporate Governance Code as the domestic standard, and the ICGN Global Governance Principles as the global standard. Here, we report the GR Scores 2018 as of December 31, 2017 in sequential form. The overall domestic average score rose 3.1 points to 51.6% from the previous year. Sixty-nine companies had higher domestic scores, and only eight companies had lower scores, compared with the previous year. Disclosing the result of board evaluations, conducting effective board meetings, and setting targets such as earnings in the medium-term management plan seemed to drive this improvement in scores. The overall global average score also rose 1.4 points to 22.3% from the previous year; however, it remains low. While 63 companies had higher global scores, 25 companies had lower scores compared with the previous year. The main reasons for the rise include easing of the requirement of independence for controlled companies by ICGN in their revised principles and a certain number of companies adopting restricted stock for management compensation. By contrast, a tightening of the independence requirement for the audit committee lowered the global scores. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Outline of the GR Scores 2018 2.1 Evaluation method 2.2 Revision of evaluation items from the GR Scores 2017 3. -

Japan's Foreign Direct Investment Experiences in India

Working Paper No. 243 Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment Experiences in India: Lessons Learnt from Firm Level Surveys Srabani Roy Choudhury December 2009 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS 1 Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... i Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... ii 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. History of Japanese Foreign Direct Investment into India ............................................. 2 2.1 The Post Liberalisation Phase-I ....................................................................................... 2 2.2 Comparison of Japanese FDI inflow into Asia and India in Phase-I ............................... 4 2.3 The Post Liberalisation Phase-II ...................................................................................... 5 3. Research Objectives and Methodology ............................................................................. 8 3.1 Objectives ....................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 10 4. Entry Strategy of Japanese Firms into India ................................................................ -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 15, 2015 Listed Company Name

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 15, 2015 Listed Company Name: Eisai Co., Ltd. Representative: Haruo Naito Representative Corporate Officer and CEO Securities Code: 4523 Stock Exchange Listings: First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange Inquiries: Sayoko Sasaki Vice President, Corporate Affairs Phone +81-3-3817-5120 Listed Company Name: Ajinomoto Co., Inc. Representative: Takaaki Nishii Representative Director, President and CEO Securities Code: 2802 Stock Exchange Listings: First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange Inquiries: Yukiko Sawa General Manager Business Strategy and Development Dept. Phone +81-3-5250-8163 AGREEMENT CONCERNING THE INTEGRATION OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE BUSINESS OF EISAI CO., LTD. AND AJINOMOTO PHARMACEUTICALS CO., LTD. BY ABSORPTION-TYPE SPLIT Aiming to become Japan’s Largest Gastrointestinal Specialty Pharma Eisai Co., Ltd. (Eisai) and Ajinomoto Co., Inc. (Ajinomoto Co.) announced that respective meetings of Eisai’s Executive Committee and Ajinomoto Co.’s Board of Directors today resolved to enter an integration agreement concerning the splitting off of a portion of Eisai’s gastrointestinal disease treatment business and its subsequent succession by Ajinomoto Co.’s wholly-owned subsidiary AJINOMOTO PHARMACEUTICALS CO., LTD. (AJINOMOTO PHARMACEUTICALS) via an absorption-type split, and on the same day, a corresponding integration agreement was signed between Eisai and Ajinomoto Co. The trade name for the new integrated company will be “EA Pharma Co., Ltd.”. Eisai will hold 60% of the shares in EA Pharma Co., Ltd., while Ajinomoto Co. will hold the remaining 40%, and the 1 company will be one of Eisai’s consolidated subsidiaries and an affiliated company accounted for by the equity-method for Ajinomoto Co. -

Corporate Governance Report

Corporate Governance Eisai Co., Ltd. Final Update: October 30, 2019 Eisai Co., Ltd. Haruo Naito, Representative Corporate Officer and CEO Contact: Masatomi Akana, Vice President, Corporate Affairs Securities Code: 4523 https://www.eisai.com/ The status of Eisai’s corporate governance is described below. I. Basic philosophy of corporate governance, capital structure, corporate profile, and other basic information 1. Basic philosophy Eisai has adopted the following Corporate Philosophy and incorporated it into the Company’s Articles of Incorporation as a commitment to our shareholders. (Corporate Philosophy) (1) The Company’s Corporate Philosophy is to give first thought to patients and their families, and to increase their benefits that health care provides. Under this Philosophy, the Company endeavors to become a human health care (hhc) company. (2) The Company’s mission is the enhancement of patient satisfaction. The Company believes that revenues and earnings will be generated as a consequence of the fulfillment of the mission. The Company places importance on this positive sequence of the mission and the ensuing results. (3) Positioning compliance, the observance of legal and ethical standards, as a core in all business activities, the Company strives to fulfill corporate social responsibilities. (4) The Company’s principal stakeholders are patients, customers, shareholders and employees. The Company endeavors to develop a good relationship with stakeholders and to enhance their value through making the following efforts: (i) Satisfying unmet medical needs, ensuring stable supply of high quality products, and providing useful information of safety and efficacy. 1 (ii) Timely disclosure of corporate management information, enhancement of corporate value, and proactive return to shareholders. -

0425 02C.Pdf

List of the “Competitiveness and Incentive Structures for Sustainable Growth ~Building Favorable Relationships between Companies and Investors~ ” Project Members Committee Chairman Kunio ITO Professor,Graduate School of Commerce and Management, Hitotsubashi University Project Members Tetsuo KITAGAWA Professor,Graduate School of International Management, Aoyama Gakuin University Shinichiro NEI Lead Executive Officer, Management Strategy(Overseas Offices), ASAHI KASEI CORPORATION Yasumasa MASUDA Senior Vice President, and Chief Financial Officer, Astellas Pharma Inc. Hajime YASUI Aarata Institute Leader, PricewaterhouseCoopers Aarata Scott CALLON Chief Executive Officer, Partner, Ichigo Asset Management, Ltd. Kenichiro YOSHIDA Senior Adviser, Ichigo Asset Management, Ltd. Ryohei YANAGI Group Officer & Head of Investor Relations, Eisai Co., Ltd. / Visiting Lecturer of Waseda University Graduate School Yoshiaki KANZAKI Senior Operating Officer, Director, Department of Strategic Think and Business Execution, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Satoshi ANDO Executive Officer, Investor Relations Headquarters, OMRON Corporation Toshiaki OGUCHI Representative Director, Governance for Owners Japan KK Taku YAMAMOTO Director of Equity Investment, Pension Investment Department, PENSION FUND ASSOCIATION Ken SHIBUSAWA Chairman, Commons Asset Management, Inc. Atsuto SAWAKAMI Chairman & Founder, Sawakami Asset Management Inc. Ryusuke OHORI Managing Director, Chief Investment Officer, JPMorgan Asset Management(Japan) Ltd. Naomi YAMAZAKI (a one‐time)Senior -

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Aug.2020)

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Aug.2020) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Market Capitalization \100mil. 1 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 228,605 2 9984 SoftBank Group Corp. 137,885 3 6861 KEYENCE CORPORATION 106,233 4 6758 SONY CORPORATION 104,781 5 9437 NTT DOCOMO,INC. 95,535 6 4519 CHUGAI PHARMACEUTICAL CO.,LTD. 79,268 7 7974 Nintendo Co.,Ltd. 74,708 8 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 70,922 9 6098 Recruit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 68,279 10 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 67,123 11 4568 DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY,LIMITED 66,980 12 9434 SoftBank Corp. 66,660 13 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 63,676 14 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 62,409 15 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 60,100 16 6367 DAIKIN INDUSTRIES,LTD. 58,520 17 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd. 53,687 18 6594 NIDEC CORPORATION 53,134 19 4661 ORIENTAL LAND CO.,LTD. 52,335 20 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 49,433 21 8001 ITOCHU Corporation 43,164 22 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 42,842 23 8035 Tokyo Electron Limited 42,682 24 6981 Murata Manufacturing Co.,Ltd. 42,441 25 2413 M3,Inc. 41,671 26 6273 SMC CORPORATION 39,242 27 7741 HOYA CORPORATION 39,148 28 4452 Kao Corporation 38,892 29 7182 JAPAN POST BANK Co.,Ltd. 38,385 30 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 37,567 31 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 37,328 32 8411 Mizuho Financial Group,Inc. 36,514 33 6902 DENSO CORPORATION 35,118 34 8766 Tokio Marine Holdings,Inc. -

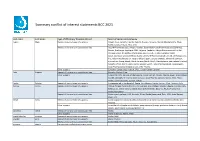

Summary Conflict of Interest Statements BCC 2021

Summary conflict of interest statements BCC 2021 Last name First name Type of affiliation/ financial interest Name of commercial company Aapro Matti Receipt of grants/research supports: Amgen, Eisai, Genomic Health, Helsinn, Hospira, Novartis, Merck, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Rache, Sandoz, Tesaro, Teva, Vifor Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees: Accord Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Astellas, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals (Schering), Biocon, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Cephalon, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Clinigen Group, Dr.Reddy's Laboratories, Eisai Co. Ltd., Eli Lilly, Genomic Health (Exact Sciences), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited, Gl Therapeutics, lnc., Helsinn Healthcare SA, Hospira (Pfizer), lpsen, Janssen Biotech, Johnson & Johnson, Kyowa Kirin Group, Merck, Merck Serono (Merck KGaA), Mundipharma International Limited, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Rache, Sandoz, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tesaro (GSK), Teva Pharmaceutical lndustries Ltd., Vifor Pharma Other support: European Cancer Organisation, SPCC, Cancer Center Genolier Aebi Stephan Receipt of honoraria or consultation fees: Novartis, Roche, Pfizer Other support: Support for CME lectures of the Lucerne Cancer Center: Amgen, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Debiopharm International SA, Eisai, Ipsen Pharma, Janssen, Merck, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Servier, Takeda André Fabrice Receipt of grants/research supports: Comepensated to the hospital: Roche, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly Barrios Carlos -

TOPIX100 Constituents (As of October 31, 2019) No. Code Issue No. Code Issue 1 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 51 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD

TOPIX100 Constituents (as of October 31, 2019) No. Code Issue No. Code Issue 1 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 51 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD. 2 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 52 7202 ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 3 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 53 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 4 1928 Sekisui House,Ltd. 54 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 5 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 55 7269 SUZUKI MOTOR CORPORATION 6 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 56 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 7 2802 Ajinomoto Co.,Inc. 57 7733 OLYMPUS CORPORATION 8 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 58 7741 HOYA CORPORATION 9 3382 Seven & I Holdings Co.,Ltd. 59 7751 CANON INC. 10 3402 TORAY INDUSTRIES,INC. 60 7832 BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. 11 3407 ASAHI KASEI CORPORATION 61 7974 Nintendo Co.,Ltd. 12 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd. 62 8001 ITOCHU Corporation 13 4188 Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Corporation 63 8002 Marubeni Corporation 14 4452 Kao Corporation 64 8031 MITSUI & CO.,LTD. 15 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 65 8035 Tokyo Electron Limited 16 4503 Astellas Pharma Inc. 66 8053 SUMITOMO CORPORATION 17 4507 Shionogi & Co.,Ltd. 67 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 18 4519 CHUGAI PHARMACEUTICAL CO.,LTD. 68 8113 UNICHARM CORPORATION 19 4523 Eisai Co.,Ltd. 69 8267 AEON CO.,LTD. 20 4528 ONO PHARMACEUTICAL CO.,LTD. 70 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 21 4543 TERUMO CORPORATION 71 8308 Resona Holdings, Inc. 22 4568 DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY,LIMITED 72 8309 Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Holdings,Inc. 23 4578 Otsuka Holdings Co.,Ltd. 73 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 24 4661 ORIENTAL LAND CO.,LTD. -

143Rd Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders

143rd Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders Christophe Weber President & CEO June 27th, 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE For the purposes of this notice, “presentation” means this document, any oral presentation, any question and answer session and any written or oral material discussed or distributed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited (“Takeda”) during the presentation. This presentation (including any oral briefing and any question-and-answer in connection with it) is not intended to, and does not constitute, represent or form part of any offer, invitation or solicitation of any offer to purchase, otherwise acquire, subscribe for, exchange, sell or otherwise dispose of, any securities or the solicitation of any vote or approval in any jurisdiction. No shares or other securities are being offered to the public by means of this presentation. No offering of securities shall be made in the United States except pursuant to registration under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended, or an exemption therefrom. This presentation is being given (together with any further information which may be provided to the recipient) on the condition that it is for use by the recipient for information purposes only (and not for the evaluation of any investment, acquisition, disposal or any other transaction). Any failure to comply with these restrictions may constitute a violation of applicable securities laws. The companies in which Takeda directly and indirectly owns investments are separate entities. In this presentation, “Takeda” is sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Takeda and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. -

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jun.2021)

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jun.2021) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Market Capitalization \100mil. 1 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 316,837 2 6758 SONY GROUP CORPORATION 136,383 3 6861 KEYENCE CORPORATION 136,366 4 9984 SoftBank Group Corp. 133,959 5 6098 Recruit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 92,769 6 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 88,709 7 7974 Nintendo Co.,Ltd. 85,084 8 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 81,505 9 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 79,839 10 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd. 77,415 11 6594 NIDEC CORPORATION 76,771 12 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 76,430 13 8035 Tokyo Electron Limited 75,587 14 4519 CHUGAI PHARMACEUTICAL CO.,LTD. 73,912 15 9434 SoftBank Corp. 69,581 16 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 64,305 17 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 61,589 18 6367 DAIKIN INDUSTRIES,LTD. 60,645 19 6902 DENSO CORPORATION 59,718 20 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 58,699 21 4661 ORIENTAL LAND CO.,LTD. 57,572 22 6981 Murata Manufacturing Co.,Ltd. 57,322 23 2413 M3,Inc. 55,069 24 7741 HOYA CORPORATION 54,457 25 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 54,101 26 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 52,625 27 8001 ITOCHU Corporation 50,716 28 3382 Seven & I Holdings Co.,Ltd. 46,954 29 4568 DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY,LIMITED 46,621 30 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 44,987 31 6273 SMC CORPORATION 44,227 32 6702 FUJITSU LIMITED 43,056 33 4689 Z Holdings Corporation 42,624 34 4901 FUJIFILM Holdings Corporation 42,400 35 8031 MITSUI & CO.,LTD. -

Different Aspects of Early and Late Development of Atrial Fibrillation

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Diferent aspects of early and late development of atrial fbrillation during hospitalization in cryptogenic stroke Ryosuke Doijiri1, Yuji Ueno2*, Muneaki Kikuno3,4, Takahiro Shimizu5, Yohei Tateishi6, Ayako Kuriki7, Hidehiro Takekawa8, Yoshiaki Shimada9, Kodai Kanemaru3,4, Yuki Kamiya7, Eriko Yamaguchi1, Masatoshi Koga3, Masafumi Ihara10, Akira Tsujino6, Koichi Hirata8, Yasuhiro Hasegawa5, Takahiko Kikuchi1, Nobutaka Hattori2 & Takao Urabe9 The detection of underlying atrial fbrillation (AF) has become increasingly possible by insertable cardiac monitoring (ICM). During hospitalization for cryptogenic stroke, factors related to the early and late development of AF have not been studied. CHALLENGE ESUS/CS is a multicenter registry of cryptogenic stroke patients undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram, continuous cardiac monitoring, and 24-h Holter electrocardiogram were all used for the detection of AF. Early and late detection of AF was determined with an allocation ratio of 1:1 among patients with AF. A total of 677 patients (68.7 ± 12.8 years; 455 men) were enrolled, and 64 patients developed AF during hospitalization. Four days after admission was identifed as the approximate median day to classify early and late phases to detect AF: ≤ 4 days, 37 patients; > 4 days, 27 patients. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that spontaneous echo contrast (SEC) (OR 5.91; 95% CI 2.19–15.97; p < 0.001) was associated with AF ≤ 4 days, whereas a large infarction > 3 cm in diameter (OR 3.28; 95% CI 1.35–7.97; p = 0.009) was associated with AF > 4 days. SEC and large infarctions were important predictors of in-hospital AF detection, particularly in the early and late stages, respectively; thus, they could serve as indications for recommending ICM.