M. Gruntman, Socks for the First Cosmonaut of Planet Earth, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Space Race

The Space Race Aims: To arrange the key events of the “Space Race” in chronological order. To decide which country won the Space Race. Space – the Final Frontier “Space” is everything Atmosphere that exists outside of our planet’s atmosphere. The atmosphere is the layer of Earth gas which surrounds our planet. Without it, none of us would be able to breathe! Space The sun is a star which is orbited (circled) by a system of planets. Earth is the third planet from the sun. There are nine planets in our solar system. How many of the other eight can you name? Neptune Saturn Mars Venus SUN Pluto Uranus Jupiter EARTH Mercury What has this got to do with the COLD WAR? Another element of the Cold War was the race to control the final frontier – outer space! Why do you think this would be so important? The Space Race was considered important because it showed the world which country had the best science, technology, and economic system. It would prove which country was the greatest of the superpowers, the USSR or the USA, and which political system was the best – communism or capitalism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvaEvCNZymo The Space Race – key events Discuss the following slides in your groups. For each slide, try to agree on: • which of the three options is correct • whether this was an achievement of the Soviet Union (USSR) or the Americans (USA). When did humans first send a satellite into orbit around the Earth? 1940s, 1950s or 1960s? Sputnik 1 was launched in October 1957. -

Details of Yuri Gagarin's Tragic Death Revealed 17 June 2013, by Jason Major

Details of Yuri Gagarin's tragic death revealed 17 June 2013, by Jason Major later, details about what really happened to cause the death of the first man in space have come out—from the first man to go out on a spacewalk, no less. According to an article published online today on Russia Today (RT.com) former cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov—who performed the first EVA on March 18, 1965—has revealed details about the accident that killed both Yuri Gagarin and his flight instructor Vladimir Seryogin in March 1968. Officially the cause of the crash was said to be the ill-fated result of an attempt to avoid a foreign object during flight training in their MiG-15UTI, a two-seated, dual-controlled training version of the widely-produced Soviet aircraft. "Foreign objects" could be anything, from balloons to flocks of birds to airborne debris to… well, you see where one could go with that. (And over the years many have.) Yuri Gagarin on the way to his historic Vostok launch on April 12, 1961. Credit: NASA Images The maneuver led to the aircraft going into a tailspin and crashing, killing both men. But experienced pilots like Gagarin and Seryogin shouldn't have lost control of their plane like On the morning of April 12, 1961, Soviet that—not according to Leonov, who has been trying cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin lifted off aboard Vostok 1 to release details of the event for the past 20 to become the first human in space, spending 108 years… if only that the pilots' families might know minutes in orbit before landing via parachute in the the truth. -

Russian Project Space Sputnik 1

Russian Project Space Sputnik 1 Sputnik 1 was the first artificial Earth satellite. The Soviet Union launched it into space because it inaugurates the The Space Age and that is when the space race started. Laika, Belka, Strelka Laika was the first dog to be sent into space who died on 3 November 1957. Belka and Strelka spent a day in space aboard and they didn’t die. Vostok 1 and Yuri Gagarin Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space in the Vostok 1 capsule.He“paved the way for space exploration and truly went where no man had been before.” Valentina Tereshkova Valentina Tereshkova is the first female to go into space.She spoke with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who said, “Valentina, I am very happy and proud that a girl from the Soviet Union is the first woman to fly into space and to operate such cutting-edge equipment.” Voskhod 2 and Alexei Leonov Voskhod 2 was another milestone in space exploration and Alexei Leonov became the first person to leave the spacecraft to conduct a spacewalk. Mir the space station Mir was a space station operated by the Soviet Union and it was the first modular space station, it was brought down in 2001. The Russian Space Programme in the 21st Century The Russian government promised to replace its key space assets, inherited from the former USSR, with a brand-new triad of space infrastructure for the 21st century. In addition to a next-generation manned spaceship, Russia committed to build a new launch site and a fleet of rockets with a wide range of capabilities. -

Engineering Lesson Plan: Russian Rocket Ships!

Engineering Lesson Plan: Russian Rocket Ships! Sputnik, Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz Launcher Schematics Uttering the text “rocket ship” can excite, mystify, and inspire young children. A rocket ship can transport people and cargo to places far away with awe-inspiring speed and accuracy. The text “rocket scientist” indexes a highly intelligent and admirable person, someone who is able to create, or assist in the creation of machines, vehicles that can actually leave the world we all call “home.” Rocket scientists possess the knowledge to take human beings and fantastic machines to space. This knowledge is built upon basic scientific principles of motion and form—the understanding, for young learners, of shapes and their function. This lesson uses the shape of a rocket to ignite engineering knowledge and hopefully, inspiration in young pupils and introduces them to a space program on the other side of the world. Did you know that the first person in space, Yuri Gagarin, was from the former Soviet Union? That the Soviet Union (now Russia) sent the first spacecraft, Sputnik I, into Earth’s orbit? That today, American NASA-based astronauts fly to Russia to launch and must learn conversational Russian as part of their training? Now, in 2020, there are Russians and Americans working together in the International Space Station (ISS), the latest brought there by an American-based commercial craft. Being familiar with the contributions Russia (and the former Soviet Union) has made to space travel is an integral part of understanding the ongoing human endeavor to explore the space all around us. After all, Russian cosmonauts use rocket ships too! The following lesson plan is intended for kindergarten students in Indiana to fulfill state engineering learning requirements. -

The Women's International Democratic Federation World

The Women's International Democratic Federation World Congress of Women, Moscow, 1963: Women’s Rights and World Politics during the Cold War By Anna Kadnikova Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Francisca de Haan CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary Abstract My thesis focuses on the June 1963 WIDF World Congress of Women that took place in Moscow, in combination with the successful space flight made by Valentina Tereshkova, the world’s first woman astronaut, just a few days before the WIDF Congress. I explore the meaning of these combined events in the context of Soviet leader Khrushchev’s policies of peaceful coexistence and peaceful competition. Based on my research of the archives of the Soviet Women’s Committee (the Soviet member of the WIDF which organized the 1963 Congress) and Soviet and American media, I argue that the Soviet Union successfully used the June 1963 events as an opportunity for public diplomacy, and showcased the USSR to the world as the champion of women’s rights. While most of the literature on the history of the Cold War is still gender blind, I attempt to show not only that the competition (peaceful and not) between the United States and the Soviet Union went beyond missiles, satellites, technology, or even agriculture, but also that their competition regarding the treatment of women by the 1960s was a key part of their rivalry. The thesis also hopes to make a meaningful contribution to the historiography of international women’s organizations in the postwar era, and in particular to the still largely unwritten history of the biggest global women’s organization, the Women’s International Democratic Federation. -

European History Quarterly 47(3)

Book Reviews 547 hearing to address the Council, providing one last sample of his oratorical skills (214). The last two chapters deal with the memory of Jerome, placing him on par with Wyclif and Hus and Martin Luther, occasionally finding his likeness with his famous beard in images from the early modern period. The book shows Jerome was an independent thinker who caused much disquiet and alarm in different European university settings. Jerome made waves across Europe and in all probability heightened university masters’ awareness of the connection between Wyclifism, already declared heresy, and the arising Hussitism. Slava Gerovitch, Soviet Space Mythologies: Public Images, Private Memories, and the Making of a Cultural Identity, University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, 2015; 256 pp., 7 b/w illus.; 9780822963639, $27.95 (pbk) Reviewed by: Andrei Rogatchevski, The Arctic University of Norway, Norway The myth about the Soviet space programme can be summarized as ‘a perfect hero conquering outer space with flawless technology’ (131). It could hardly have been otherwise in a censorship-ridden country that used space exploration, in particular, to prove the superiority of socialism over capitalism. A great deal of information about the programme was for decades routinely concealed not only from the gen- eral public but also from the Communist rulers, whose versions of space flight communication transcripts were doctored for fear of funding withdrawal. Even the cosmonauts and their ground control sometimes did not want to enlighten each other (until afterwards) about the full scale of in-flight problems. Thus, Gagarin, while in orbit, was misinformed about its height, because his engines turned themselves off too late and propelled his spacecraft to an apogee of 188 miles, instead of the expected 143 miles. -

From Yuri Gagarin to Apollo-Soyuz

H-Diplo National Security Archive: U.S.-Soviet Cooperation in Outer Space: From Yuri Gagarin to Apollo-Soyuz Discussion published by Malcolm Byrne on Monday, April 12, 2021 Cold War Rivals Joined Forces after Historic Gagarin Flight in 1961 to Pursue Broader Shared Interests, Documents Show Current Collaboration on International Space Station Has Its Roots in JFK- Khrushchev Meeting of Minds Edited by Sarah Dunn Washington, D.C., April 12, 2021 – Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s historic spaceflight 60 years ago, which made him the first human in space, prompted President John F. Kennedy to advance an unusual proposal – that the two superpowers combine forces to cooperate in space. In a congratulatory letter to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, posted today by the nongovernmental National Security Archive, Kennedy expressed the hope that “our nations [can] work together” in the “continuing quest for knowledge of outer space.” Kennedy’s letter is one of many records in the American and Russian archives that show that the two ideological rivals have not only engaged in a space race but have also cooperated for decades. In fact, as the ongoing joint activities involving the International Space Station demonstrate, space has been one of the few spheres of collaboration that have survived the trials and tensions of the Cold War, keeping both countries engaged in constructive competition as well as in joint efforts to expand human frontiers. Today’s posting begins a two-part series exploring this often-overlooked chapter in the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, and later Russia. The materials in the first tranche cover events from Gagarin’s flight to the celebrated Apollo-Soyuz mission. -

Space Exploration

Space Exploration Learning Objectives: To consider reasons for space exploration. To learn a brief history of space travel. Reasons for and against going to space For Against To make important scientific It is very expensive. discoveries. To better understand our It might put lives in danger. world. It is only natural to explore. There are more important things on Earth to discover. To find other life forms. We might make unpleasant discoveries. Yuri Gagarin • 9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968, Soviet pilot and cosmonaut. • The first human to journey into outer space in Vostok 1 spacecraft on April 12, 1961. After re-entry, Gagarin ejected from the craft and landed safely by parachute. • After the mission, Gagarin became an international celebrity, and was awarded many medals and honours. • Vostok 1 was his only spaceflight. • Gagarin died when his training jet crashed in 1968. The precise cause of the crash is uncertain. Russian Rouble commemorating Gagarin in 2001 Valentina Tereshkova • Chosen out of more than 400 applicants. • She was selected to pilot Vostok 6 on the 16th of June 1963 - almost 50 years ago! • During her 3 day mission, she performed various tests on herself to collect data on the female body's reaction to spaceflight. • Before being recruited as a cosmonaut, Tereshkova worked in a textile-factory and was an amateur parachutist. • After her space career she worked in Russian politics. Laika • The name comes from the Russian word for ‘barker’. • She was a stray dog from the streets of Moscow who had to undergo special training. • Died after a few hours from overheating; however the Russian government claimed that she was euthanised before her oxygen ran out. -

September 16, 1958 Letter, Sergei Korolev to Comrade K.N. Rudnev

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 16, 1958 Letter, Sergei Korolev to Comrade K.N. Rudnev Citation: “Letter, Sergei Korolev to Comrade K.N. Rudnev,” September 16, 1958, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Selected, edited, and annotated by Asif Siddiqi. Translated by Gary Goldberg and Angela Greenfield. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/260529 Summary: Proposal from Sergei Korolev submitted to the State Committee for Defense Technology to develop a spy satellite with a cosmonaut on board. Credits: This document was made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York (CCNY). Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document New Sources on Yuri Gagarin (April 2021) DOCUMENT No. 2 Proposal to develop a spy satellite with a cosmonaut on board from Sergei Korolev submitted to the State Committee for Defense Technology. – Asif Siddiqi Outgoing Nº s/693ss/ov September 16, 1958 Top Secret of Special Importance Copy Nº 2 TO COMRADE K. N. RUDNEV [1] We submit for your consideration proposals to develop a reconnaissance satellite in two versions: a completely automated artificial oriented reconnaissance satellite (object OD-1) and an oriented reconnaissance satellite with a man on board (object OD-2). In the event of your agreement to conduct work on two versions of a reconnaissance satellite it would be advisable to submit the appropriate proposals for the consideration of the Council of Ministers’ Commission on Military Industrial Questions for preparation of a draft Decree about this work. Since at the present time Comrade G. N. PASHKOV has already worked on a draft Government Decree about the first automated version of a reconnaissance satellite (OD-1), we have sent Comrade G. -

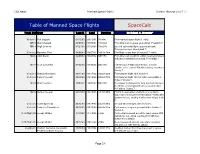

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Human Spaceflight Plans of Russia, China and India

Presentation to the Secure World Foundation November 3, 2011 by Marcia S. Smith Space and Technology Policy Group, LLC and SpacePolicyOnline.com “Civil” Space Activities in Russia “Civil” space activities Soviet Union did not distinguish between “civil” and “military” space programs until 1985 Line between the two can be quite blurry For purposes of this presentation, “civil” means Soviet/Russian activities analogous to NASA and NOAA (though no time to discuss metsats today) Roscosmos is Russian civil space agency. Headed by Army General (Ret.) Vladimir Popovkin Recent reports of $3.5 billion budget, but probably does not include money from US and others 11-03-11 2 Key Points to Take Away Space cooperation takes place in the broad context of U.S.-Russian relations Russia may not be a superpower today, but it is a global power and strategically important to the United States Complex US-Russian relationship, as New START and INKSNA demonstrate Russian space program modest by Soviet standards, but Retains key elements Leverages legacy capabilities for current activities and commercial gain Is a global launch service provider from four launch sites from Arctic to equator Proud history of many space “firsts,” but also tragedies and setbacks U.S.-Soviet/Russian civil space relationship has transitioned from primarily competition to primarily cooperation/interdependence today Cooperation not new, dates back to 1963, but much more intensive today U.S. is dependent on Russia for some things, but they also need us Bold dreams endure as Mars 500 demonstrates 11-03-11 3 Today is 54th Anniversary of First Female in Space 11-03-11 4 Just One of Many “Firsts” First satellite (Sputnik, Oct. -

Cumilla Govt. City College Half-Yearly Examination-2021 Class- XI Subject- English 1St & 2Nd Paper (107&108) Full Marks- 50 English 1St Paper 1

Cumilla Govt. City College Half-Yearly Examination-2021 Class- XI Subject- English 1st & 2nd Paper (107&108) Full Marks- 50 English 1st Paper 1. Read the passage and answer the questions A and B. Valentina Tereshkova(born on 6 March 1937). Valentina Tereshkova was born in the village Maslennikovo, Tutayevsky District in Central Russia. Tereshkova’s father was a tractor driver and her mother worked in a textile plant. Tereshkova began school in 1945 at the age of eight, but left school in 1953 and continued her education through distance learning. She became interested in parachuting from a young age, and trained in skydiving at the local Aeroclub, making her first jump at age 22 on 21 May 1959. At that time she was employed as a textile worker in a local factory. It was her expertise in skydiving that led to her selection as a cosmonaut. After the flight of Yuri Gagarin (the first human being to travel to outer space in 1961), the Soviet Union Ò decided to send a woman in space .On 16 February 1962, proletaria” Valentina Tereshkova was selected for this project from among more than four hundred applicants. Tereshkova had to undergo a series of training that included weightless flights, isolation tests, centrifuge tests, rocket theory, spacecraft engineering, 120 parachute jumps and pilot training in MiG-15UTI jet fighters. Since the successful launch of the spacecraft Vostok-5 on 14 June 1963, Tereshkova began preparing for her own flight. On the morning of 16 June 1963, Tereshkova and her back-up cosmonaut Solovyova were dressed in space-suits and taken to the space shuttle launch pad by a bus.