Citizens United, Issue Ads and Radio: an Empirical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and Media Impacts Gino Tozzi Jr

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2011 Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and media impacts Gino Tozzi Jr. Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Tozzi Jr., Gino, "Approval of George W. Bush: Economic and media impacts" (2011). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 260. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. APPROVAL OF GEORGE W. BUSH: ECONOMIC AND MEDIA IMPACTS by GINO J. TOZZI JR. DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: POLITICAL SCIENCE Approved by: _________________________________ Chair Date _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY GINO J. TOZZI JR. 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my Father ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my committee chair Professor Ewa Golebiowska for the encouragement and persistence on only accepting the best from me in this process. I also owe my committee of Professor Ronald Brown, Professor Jodi Nachtwey, and Professor David Martin a debt of gratitude for their help and advisement in this endeavor. All of them were instrumental in keeping my focus narrowed to produce the best research possible. I also owe appreciation to the commentary, suggestions, and research help from my wonderful wife Courtney Tozzi. This project was definitely more enjoyable with her encouragement and help. -

Good Karma Brands to Purchase E.W. Scripps' WTMJ, WKTI Radio Stations in Milwaukee July 27, 2018 (Milwaukee, Wis.): Good Karma

Good Karma Brands to Purchase E.W. Scripps’ WTMJ, WKTI Radio Stations in Milwaukee July 27, 2018 (Milwaukee, Wis.): Good Karma Brands, LLC announced plans to purchase WTMJ (620 AM and 103.3 FM) and WKTI (94.5 FM) from The E.W. Scripps Company (NASDAQ: SSP). Good Karma Brands, which is headquartered in Milwaukee, owns and operates six ESPN affiliated radio stations, including two in Wisconsin – 540 ESPN (WAUK-AM) in Milwaukee, and 100.5 ESPN (WTLX-FM) in Madison. Its Wisconsin radio assets also include a local news talk station (1430 WBEV-AM) and a country music station (95.3 WXRO-FM) in Beaver Dam. “We’re thrilled to welcome WTMJ and WKTI to the GKB family,” said Craig Karmazin, Good Karma Brands founder and chief executive officer. “The heritage, prestige, and team at the stations, in addition to their incredible sports partnerships, fit our commitment to provide best-in- class opportunities for our teammates, content for our fans, and solutions for our marketing partners.” Good Karma Brands is a sports media and entertainment company with expertise in local sports marketing activation. Its assets include a number of premium brands, including an events division that produces the Wisconsin Sports Awards, the Tundra Trio hospitality houses in Green Bay, and the Cheribundi Tart Cherry Boca Raton Bowl, as well as ESPN media assets in Baltimore (Digital), Cleveland (Digital/Radio), Madison (Digital/Radio), Milwaukee (Digital/Radio), Washington D.C. (Digital) and West Palm Beach (Digital/Radio). The transaction will be filed with the FCC and upon approval, is expected to close in fourth quarter. -

Linda Baun's Dedication Will Leave

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 CHAIR’S COLUMN Prepare for election season Baun takes bow after 14 years at WBA We are now entering the election window. One very WBA Vice President Linda Baun will retire from the important heads up: You must upload everything organization in September after 14 years. to your Political File (orders, copy, audio or video) Baun joined the WBA in 2006 and led numerous WBA as soon as possible. As soon as possible is the catch events including the Broadcasters Clinic, the WBA phrase. Numerous broadcast companies, large and Awards for Excellence program and Awards Gala, the small, have signed off on Consent Decrees with the Student Seminar, the winter and summer confer- FCC for violating this phrase. What I have been told is, ences, and many other WBA events including count- get it in your Political File by the next day. less social events and broadcast training sessions. She Linda Baun Chris Bernier There are so many great examples of creative pro- coordinated the WBA’s EEO Assistance Action Plan, WBA Chair gramming and selling around the state. Many of you ran several committees, and handled administration are running the classic Packer games in place of the of the WBA office. normal preseason games. With high school football moved to the “Linda’s shoes will be impossible to fill,” said WBA President and CEO spring in Michigan our radio stations there will air archived games Michelle Vetterkind. “Linda earned a well-deserved reputation for from past successful seasons. This has been well received and we always going above and beyond what our members expected of her were able to hang on to billing for the fall. -

Who Is the Attorney General's Client?

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\87-3\NDL305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-APR-12 11:03 WHO IS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S CLIENT? William R. Dailey, CSC* Two consecutive presidential administrations have been beset with controversies surrounding decision making in the Department of Justice, frequently arising from issues relating to the war on terrorism, but generally giving rise to accusations that the work of the Department is being unduly politicized. Much recent academic commentary has been devoted to analyzing and, typically, defending various more or less robust versions of “independence” in the Department generally and in the Attorney General in particular. This Article builds from the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, in which the Court set forth key principles relating to the role of the President in seeing to it that the laws are faithfully executed. This Article draws upon these principles to construct a model for understanding the Attorney General’s role. Focusing on the question, “Who is the Attorney General’s client?”, the Article presumes that in the most important sense the American people are the Attorney General’s client. The Article argues, however, that that client relationship is necessarily a mediated one, with the most important mediat- ing force being the elected head of the executive branch, the President. The argument invokes historical considerations, epistemic concerns, and constitutional structure. Against a trend in recent commentary defending a robustly independent model of execu- tive branch lawyering rooted in the putative ability and obligation of executive branch lawyers to alight upon a “best view” of the law thought to have binding force even over plausible alternatives, the Article defends as legitimate and necessary a greater degree of presidential direction in the setting of legal policy. -

The Case of the “Ground Zero Mosque” Controversy

A Theoretical Study of Solidarity in American Society: The Case of the “Ground Zero Mosque” Controversy Fatemeh Mohammadi1 * , Hamed Mousavi2 1. PhD Candidate in Anthropology, Carleton University, Canada (Corresponding Author: [email protected]) 2. Assistant Professor, Department of Regional Studies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran ([email protected]) (Received: 5 Mar. 2017 Accepted: 8 Aug. 2017) Abstract The paper uses the case study of the controversy regarding the construction of a mosque near the site of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in Manhattan, New York, to analyze the different theoretical approaches to the concept of solidarity. It is argued that the presence of affectional solidarity which is based on feelings of caring, friendship and love was very limited in the case under study. Instead the primary form of solidarity present in the ground zero mosque debate was conventional solidarity, which is based primarily on common interests and concerns that are established through shared traditions and values. Nevertheless, conventional solidarity uses membership within a group to advocate for solidarity. In many instances however, people in need of solidarity might fall outside of the boundaries of “we,” and as a result limiting the utility of the approach. This is why the paper advocates for a revised form of Jodi Dean’s reflective solidarity, which is based on mutual responsibility toward each other despite our differences. It is argued that in its current form this approach is a normative universal ideal which holds great potential but is unclear, underspecified and impractical. However, by injecting some “realism” into this theoretical approach, reflective solidarity is superior to affectional and conventional approaches. -

Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters Conducted September 14, 2008 by Rasmussen Reports for FOX News

Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters Conducted September 14, 2008 By Rasmussen Reports for FOX News 1* How do you rate the way that George W. Bush is performing his role as President? Excellent, good, fair, or poor? 13% Excellent 20% Good 16% Fair 50% Poor 1% Not sure 2* How do you rate the way that Bill Ritter is performing his role as Governor? Excellent, good, fair, or poor? 14% Excellent 30% Good 30% Fair 24% Poor 1% Not sure 3* If the Presidential Election were held today, would you vote for Republican John McCain, Democrat Barack Obama, Libertarian Bob Barr or Independent Ralph Nader 48% McCain 46% Obama 1% Barr 3% Nader 0% McKinney 2% Not sure 4* Favorable Ratings Obama McCain Very Favorable 37% 26% Somewhat Favorable 15% 29% Somewhat Unfavorable 15% 18% Very Unfavorable 31% 24% Not sure 2% 3% 5* In terms of how you will vote for President, are you primarily interested in National Security issues such as the War with Iraq and the War on Terror, Economic issues such as jobs and economic growth, Domestic Issues like Social Security and Health Care, Cultural issues such as same-sex marriage and abortion, or Fiscal issues such as taxes and government spending? 27% National Security Issues 35% Economic Issues 13% Domestic Issues 7% Cultural Issues 12% Fiscal Issues 6% Not sure 6* Overall, which candidate do you trust more -- Barack Obama or John McCain? 46% Obama 48% McCain 6% Not sure Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters continued 7* Regardless of how you would vote, how comfortable would you be with Barack Obama as president? 32% -

Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters Conducted September 7, 2008 by Rasmussen Reports for FOX News

Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters Conducted September 7, 2008 By Rasmussen Reports for FOX News 1* How do you rate the way that George W. Bush is performing his role as President? Excellent, good, fair, or poor? 15% Excellent 22% Good 14% Fair 49% Poor 0% Not sure 2* How do you rate the way that Bill Ritter is performing his role as Governor? Excellent, good, fair, or poor? 16% Excellent 33% Good 27% Fair 21% Poor 2% Not sure 3* If the Presidential Election were held today, would you vote for Republican John McCain, Democrat Barack Obama, Libertarian Bob Barr, Independent Ralph Nader or Green Party candidate Cynthia Ann McKinney? 46% McCain 49% Obama 2% Barr 0% Nader 0% McKinney 2% Not sure 4* Favorable Ratings Obama McCain Biden Palin Very Favorable 36% 30% 30% 41% Somewhat Favorable 18% 31% 23% 13% Somewhat 20% 18% 18% 12% Unfavorable Very Unfavorable 25% 21% 25% 31% Not sure 2% 1% 4% 3% Colorado Survey of 500 Likely Voters continued 5* In terms of how you will vote for President, are you primarily interested in National Security issues such as the War with Iraq and the War on Terror, Economic issues such as jobs and economic growth, Domestic Issues like Social Security and Health Care, Cultural issues such as same-sex marriage and abortion, or Fiscal issues such as taxes and government spending? 25% National Security Issues 44% Economic Issues 13% Domestic Issues 5% Cultural Issues 7% Fiscal Issues 6% Not sure 6* Overall, which candidate do you trust more -- Barack Obama or John McCain? 44% Obama 49% McCain 7% Not sure 7* Regardless -

The Value of Claiming Torture: an Analysis of Al-Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back, 43 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 43 | Issue 1 2010 The alueV of Claiming Torture: An Analysis of Al- Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back Michael J. Lebowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael J. Lebowitz, The Value of Claiming Torture: An Analysis of Al-Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back, 43 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 357 (2010) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol43/iss1/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. File: Lebowitz 2 Created on: 1/9/2011 9:48:00 PM Last Printed: 4/5/2011 8:09:00 PM THE VALUE OF CLAIMING TORTURE: AN ANALYSIS OF AL-QAEDA’S TACTICAL LAWFARE STRATEGY AND EFFORTS TO FIGHT BACK Michael J. Lebowitz* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 357 II. CLAIMING TORTURE TO SHAPE THE BATTLEFIELD .............................. 361 A. Tactical Lawfare ........................................................................... 362 B. Faux Torture ................................................................................. 364 C. The Torture Benchmark ............................................................... -

The Ground Zero Mosque Controversy: Implications for American Islam

Religions 2011, 2, 132-144; doi:10.3390/rel2020132 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Ground Zero Mosque Controversy: Implications for American Islam Liyakat Takim Sharjah Chair in Global Islam, McMaster University, University Hall, 116, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4K1, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1 (647) 865 7863 Received: 29 March 2011; in revised form: 22 May 2011 / Accepted: 31 May 2011 / Published: 7 June 2011 Abstract: The controversy surrounding the “ground zero mosque” is part of a larger debate about the place of Islam in U.S. public space. The controversy also reveals the ways in which the boundaries of American identity continue to be debated, often through struggles over who counts as a “real” American. It further demonstrates the extent to which Islam is figured as un-American and militant, and also the extent to which all Muslims are required to account for the actions of those who commit violence under the rubric of Islam. This paper will discuss how, due to the events of September 11, 2001, Muslims have engaged in a process of indigenizing American Islam. It will argue that the Park51 Islamic Community Center (or Ground Zero mosque) is a reflection of this indigenization process. It will go on to argue that projects such as the Ground Zero mosque which try to establish Islam as an important part of the American religious landscape and insist on the freedom of worship as stated in the U.S. constitution, illustrate the ideological battlefield over the place of Islam in the U.S. -

Obama's Poll Numbers Are Falling to Earth by DOUGLAS E. SCHOEN and SCOTT RASMUSSEN

Obama's Poll Numbers Are Falling to Earth By DOUGLAS E. SCHOEN and SCOTT RASMUSSEN It is simply wrong for commentators to continue to focus on President Barack Obama's high levels of popularity, and to conclude that these are indicative of high levels of public confidence in the work of his administration. Indeed, a detailed look at recent survey data shows that the opposite is most likely true. The American people are coming to express increasingly significant doubts about his initiatives, and most likely support a different agenda and different policies from those that the Obama administration has advanced. Polling data show that Mr. Obama's approval rating is dropping and is below where George W. Bush was in an analogous period in 2001. Rasmussen Reports data shows that Mr. Obama's net presidential approval rating -- which is calculated by subtracting the number who strongly disapprove from the number who strongly approve -- is just six, his lowest rating to date. • Obama’s job approval has been strong and steady in the mid-60’s o Gallup 3-day tracking has it at 62% approve, 27% disapprove • In the 5 most recent polls, Obama’s job approval has averaged 61% (Real clear politics average) and Rasmussen’s data has the lowest numbers. • Over the last five weeks, Rasmussen is consistently 2 -4 points lower on approval than the average of all approval polls released that week. • Obama is not below where GWB was in 2001. March 11, 2001 Gallup = 58% approval rating of GWB (29% disapprove) Rasmussen Reports shows a 56%-43% approval, with a third strongly disapproving of the president's performance. -

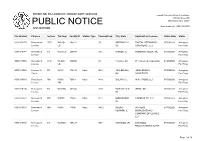

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-200803-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 08/03/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000119275 Renewal of LPD WNGS- 190222 33 GREENVILLE, DIGITAL NETWORKS- 07/30/2020 Accepted License LD SC SOUTHEAST, LLC For Filing 0000119148 Renewal of FX W253CR 200584 98.5 MARION, IL FISHBACK MEDIA, INC. 07/30/2020 Accepted License For Filing 0000118904 Renewal of LPD WLDW- 182006 23 Florence, SC DTV America Corporation 07/29/2020 Accepted License LD For Filing 0000119388 License To FS KLRC 174140 Main 90.9 TAHLEQUAH, JOHN BROWN 07/30/2020 Accepted Cover OK UNIVERSITY For Filing 0000119069 Renewal of FM WISH- 70601 Main 98.9 GALATIA, IL WISH RADIO, LLC 07/30/2020 Accepted License FM For Filing 0000119104 Renewal of FX W230BU 142640 93.9 ROTHSCHILD, WRIG, INC. 07/30/2020 Accepted License WI For Filing 0000119231 Renewal of FM WXXM 17383 Main 92.1 SUN PRAIRIE, CAPSTAR TX, LLC 07/30/2020 Accepted License WI For Filing 0000119070 Renewal of AM WMIX 73096 Main 940.0 MOUNT WITHERS 07/30/2020 Accepted License VERNON, IL BROADCASTING For Filing COMPANY OF ILLINOIS, LLC 0000119330 Renewal of FX W259BC 155147 99.7 BARABOO, WI BARABOO 07/30/2020 Accepted License BROADCASTING CORP. For Filing Page 1 of 29 REPORT NO. PN-1-200803-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 08/03/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. -

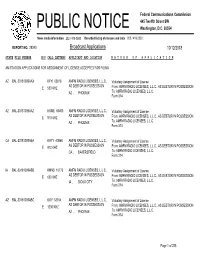

Broadcast Applications 10/12/2018

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 29340 Broadcast Applications 10/12/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING AZ BAL-20181009AAX KFYI 63918 AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., Voluntary Assignment of License AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION E 550 KHZ From: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION AZ , PHOENIX To: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C. Form 314 AZ BAL-20181009AAZ KGME 65480 AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., Voluntary Assignment of License AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION E 910 KHZ From: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION AZ , PHOENIX To: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C. Form 314 CA BAL-20181009ABA KHTY 40868 AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., Voluntary Assignment of License AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION E 970 KHZ From: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION CA , BAKERSFIELD To: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C. Form 314 IA BAL-20181009ABB KMNS 10775 AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., Voluntary Assignment of License AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION E 620 KHZ From: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION IA , SIOUX CITY To: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C. Form 314 AZ BAL-20181009ABC KOY 63914 AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., Voluntary Assignment of License AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION E 1230 KHZ From: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C., AS DEBTOR IN POSSESSION AZ , PHOENIX To: AMFM RADIO LICENSES, L.L.C.