M19187 Equality and Diversity Guidance V4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINUTES of the Annual General Meeting of the Association of Democratic Services Officers Held on Monday 15Th November 2010 at 4

Business Address; ADSO, Newfrith House, 21 Hyde Street, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 7DR MINUTES of the Annual General Meeting of the Association of Democratic Services Officers held on Monday 15th November 2010 at 4.15 pm in the Hilton Leeds City Hotel, Leeds 1. PRESENT: Andrew Brett. Andrew Brett Associates South East Julie Batt. Basildon Borough Council East England Jo Morrison. Bath and NE Somerset South West Georgina Atkinson. Blackpool Council North West Katherine McDonnell Blackpool Council North West Laura Latham Blackpool Council North West Alistair Peace. Braintree District Council East England Clive Parker. Buckinghamshire County Council South East Matthew Archer. Canterbury City Council South East Mike Hooper Charnwood E. Midlands James Doble. Cherwell District Council South East Natasha Clark. Cherwell District Council South East Mandy Ramsden. Cheshire West and Chester North West Jacqui Daniels. City of London Corporation London Lorraine Brook. City of London Corporation London Helen Abraham. Coventry City Council W.Midlands Daniel Cooper. Derby City Council E.Midlands Ellen Bird. Derby City Council E.Midlands Rob Hooper. Devon County Council South West Tracy Couper. East Cambridgeshire District Council East England Andrea Costley. East Staffordshire Borough Council W.Midlands Susan Coulter. Fareham Borough Council South East Patricia Sutton. Forest Heath Council East England Trisha Sutton Forest Heath D C East England Julie Jones. Forest of Dean District Council South West Julie Hill. Gloucestershire Council South West Sian Clarke. Herefordshire Council W.Midlands Rebecca Owen. Hinkley and Bosworth District Council E.Midlands Helen Gee. Hyndburn Borough Council North West Jan Robinson. Ipswich Borough Council East England Pauline Ferris. LB Harrow London Association of Democratic Services Officers Registered Office: Steele Robertson Goddard, 28 Ely Place, London EC1N 6AA Registration Number: 7068088 Place of Registration: England and Wales Zoe Cooke Leeds City Yorks Nigel West. -

Milton Keynes Council - Appointments to Outside Bodies

MILTON KEYNES COUNCIL - APPOINTMENTS TO OUTSIDE BODIES POLICY AND RESOURCES ORGANISATION CURRENT REPRESENTATIVE EXPIRY DATE TERM OF OFFICE Association of Councils in Representatives: the Thames Valley Region Vacant (ACTVAR) Councillor K Wilson Deputies: May 1999 Annual Councillor Bartlett Councillor Pym Observers: Councillor Hopkins Councillor Tallack Bedford/Milton Councillor Bristow May 1999 Annual Keynes/Northampton Councillor Ellis Regional Forum Councillor I Henderson Councillor K Wilson Bucks Association of Local Councillor Tapp May 1999 Annual Councils Bucks Forum Councillor Hopkins Councillor O’Sullivan May 1999 Annual 1 Vacancy Buckinghamshire Councillor Edwards May 1999 Annual Superannuation Fund Investment Board L:\Resources IT\mel\Minutes to be converted\1998-99\enl_Minutes_10945_Minutes_ANNEX.doc 1 L:\Resources IT\mel\Minutes to be converted\1998-99\enl_Minutes_10945_Minutes_ANNEX.doc 2 POLICY AND RESOURCES (2) ORGANISATION APPOINTMENTS MADE EXPIRY DATE TERM OF OFFICE CNT Local Liaison Councillor Bates Committee Councillor Bristow Councillor I Henderson May 1999 Annual Councillor Miller Councillor O’Sullivan Councillor K Wilson Health Authorities and Local Councillor Conchie (Rep) Authorities in Bucks JCC Councillor I Wilson (Deputy) May 1999 Annual Local Government Councillor Kilkenny Association General Councillor Pym May 1999 Annual Assembly Councillor K Wilson 1 Vacancy Local Government Councillor Conchie May 1999 Annual Association New Towns Special Interest Group Local Government Councillor Edwards Association Urban -

Waste Collection Commitment Signatories

Signatories to the Waste Collection Commitment North East Eastern Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council Peterborough City Council Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Fenland District Council Hartlepool Borough Council Tendring District Council Darlington Borough Council Maldon District Council Gateshead Council Colchester Borough Council Durham Council Chelmsford Borough Council Middlesbrough Council Castle Point Borough Council North Tyneside Borough Council Braintree District Council North Norfolk District Council North West St Edmundsbury Borough Council Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Forest Heath District Council Hyndburn Borough Council Central Bedfordshire Council Fylde Borough Council South Cambridgeshire District Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Southend-on-Sea Borough Council Cheshire East Council Dacorum Borough Council Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Broadland District Council Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council Hertsmere Borough Council Wyre Borough Council South Ribble Borough Council East Midlands Stockport Council Chesterfield Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council West Midlands Charnwood Borough Council Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Blaby District Council Stratford-on-Avon District Council West Lindsey District Council Shropshire Council North Kesteven District Council Wolverhampton City Council South Holland District Council Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Boston Borough Council Lichfield District Council South Kesteven District Council Stafford Borough Council Lincoln City -

1 Response to Inspector's Document ID/9 Updated Housing Technical Paper- Submission Document B126 1. Introduction 1.1 the In

Response to Inspector’s document ID/9 Updated Housing Technical Paper- Submission Document B126 1. Introduction 1.1 The Inspector has asked for an update to the Housing Topic Paper (HTP) prepared in February 2011. This statement responds to the request for an update, clarifying the parts of the HTP that remain relevant and updating those areas where new information is available to support the Council’s position. The role of the Housing Topic Paper 1.2 The HTP was produced to support and justify the Council’s decision to revise its Core Strategy housing target to make it more realistic and deliverable. The Council’s view is that the housing target included in the Core Strategy Revised Proposed Submission (October 2010) remains relevant and appropriate, and that activity in the housing market over the last two years continues to support the Council’s position. 1.3 As such, the background to as to why the Council altered its housing target to deliver 28,000 homes over the plan period (2010-2026) remains as per the HTP of February 2011. 1.4 What has been updated is factual information regarding the rate of house building, land availability and market indicators. There has also been progress on the delivery of key sites, which further supports the position put forward by the Council in the HTP. An update has also been provided covering some of the key issues raised by the publication of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). This new information is set out below. 2. Key reports and new data Five Year Land Supply Report 2.1 The Council published a new Five-Year Land Supply Report in December 20111 covering the period April 2012 to March 2017. -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

Are You Ready A5 Booklet V2.Indd

Household emergency plan - type in the white boxes. Where we will meet if we can’t get into, or stay in our home? Who will collect children from school if we are unable to get there? Who Contact no. Neighbours we will check on. Who Contact no. Where we turn off: gas water electricity 22 Who can we stay with if we are evacuated? Who Contact no. Who can be our emergency friend to get medicine and supplies if we have to stay at home? Who Contact no. Who will look after our pets if we are unable to? Who Contact no. Local Radio Station Frequency Heart (Oxford) 97.4, 102.6 Asian Star (Slough) 101.6 Heart (Reading) 87.0, 102.9 Banbury Sound 107.6 Jack FM 106.4, 106.8 BBC Radio Berkshire 94.6, 95.4, 104.1, Mix 96 96.2 104.4 Newbury Sound 105.6, 107.4 BBC Oxford 95.2 Oxford 107.9 107.9 BBC Three Counties 90.4, 92.1, 94.7, Reading 107 107.0 95.5, 98.0, 103.8 Time FM 106.6 Heart (Bucks) 97.6 BBC Asian Network (MK) 630 AM Heart (MK) 103.3 Gold (Bucks) 828 AM 23 Emergency contact list You should type in and store these contact details. Name Number Work Doctor School(s) Water supplier Electricity supplier Gas supplier Telephone supplier Home insurance company Home breakdown services Emergency friend Floodline quick dial number Further Information Organisation Website and Phone Number Emergency Services 999 Non emergency police 0845 8 505 505 NHS Direct www.nhs.uk 0845 4647 Anti-Terrorism Hotline 0800 789 321 Environment Agency www.environment-agency.gov.uk/ General Enquiries 08708 506 506 Floodline 0845 988 1188 Incident Reporting 0800 80 70 60 DirectGov -

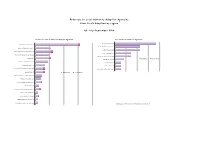

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

Winners of the Geoplace Exemplar Awards 2014

Winners of the GeoPlace Exemplar Awards 2014 Exemplar Award 2014 Winner Joint Emergency Services Group (Wales) Runner-up Oxford City Council Highly commended Northumberland County Council Custodian of the Year 2014 Marilyn George East Riding of Yorkshire Most Improved Address Data Ribble Valley Borough Council Most Improved Street Data Milton Keynes Council Best Address Data in Region Best Address Data in East Midlands Region 2014 Mansfield District Council Best Address Data in East of England Region 2014 Huntingdonshire District Council Best Address Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Enfield Best Address Data in North East Region 2014 South Tyneside Council Best Address Data in North West Region 2014 Allerdale Borough Council 1 Best Address Data in South East Region 2014 Lewes District Council Best Address Data in South East Region 2014 Adur District Council Best Address Data in South West Region 2014 Torridge District Council Best Address Data in Wales Region 2014 Flintshire County Council Best Address Data in West Midlands Region 2014 Wyre Forest District Council Best Address Data in Yorkshire and the Humber Region 2014 Kingston upon Hull City Council and Sheffield City Council Best Street Data in Region Best Street Data in East Midlands Region 2014 Northamptonshire County Council Best Street Data in East of England Region 2014 Peterborough City Council Best Street Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Enfield Best Street Data in Greater London Region 2014 London Borough of Hillingdon Best Street Data -

Appendix D STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL

Appendix D West Berkshire Council Senior Management Review STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Prepared for: Nick Carter Chief Executive West Berkshire Council Market Street Newbury RG14 5LD Prepared by: Jennifer McNeill Chartered Fellow CIPD; MA; BEd The Guildhall, High Street Regional Director Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 9GH South East Employers Telephone: 01962 840664 1 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.seemp.co.uk 29 October 2018 (revised) 2 1. Context and purpose of review 1.1 West Berkshire Council (WBC) is aware that, given the higher age profile of senior managers (many are approaching 60 years of age), a number may retire soon (likely within 2-5 years). Therefore, as part of its workforce and succession planning process, the council seeks to commence early discussions about the current structure and the potential for realignment to meet future service demands and challenges, including scarcer resources and increasing competition in certain areas. 1.2 Workforce planning provides the means to review and redefine the senior manager structure to meet emerging demands and challenges in the medium to longer term. Early consideration can be given to the future shape and structure of the senior management team to meet changing service demands prior to vacancies starting to appear. 1.3 The development of a ‘blue-print’ to take the structure forward will inform decision- making for either a planned process of revising the structure, or to manage vacancies individually as they start to arise. 1.4 The council needs to be able to respond to any skills shortage areas or particular recruitment or retention difficulties. Is the council positioned to attract high level, or difficult to recruit to, skills to fill senior level vacancies when they arise in the short and medium term? 1.5 A planned approach will minimise disruption to service provision in those areas if the situation arises. -

Financial Review

MOVING FORWARD SUCCESSFULLY Staffing Statistics 2008 We employ 815 staff For nearly 50 years, Richmond Fellowship (RF) has been a registered charity and social landlord, offering housing, care and support and for 22 years, employment support to Ethnicity of Staff % people with mental health problems. White 78.60 Mixed 1.50 Our principal regulator is the Housing Corporation, although we operate in close partnership with Asian 3 many agencies and authorities throughout England who monitor our performance and provision Black 11 of support services to nearly 6,000 people. To deliver our range of high quality services Other successfully we rely on a highly skilled workforce, well trained, dedicated and motivated, and 0.85 backed by an efficient central support mechanism that enables them to apply their knowledge to QR 6 best use. RF employs 815 staff across all disciplines who have opportunities to develop themselves both professionally and vocationally. Gender Female 71 From the 1 April 2007, RF merged with RFET and traded throughout the year as a single entity. Male 21 Following the implementation of the single entity structure, RF has maintained sound financial management techniques. The internal controls framework was proven to be robust and the annual accounts were accompanied by a clean audit report. The financial operating environment Age % continued to be challenging but the results show that we, again, outperformed budget and the <21 0.50 previous year’s numbers. RF’s operational surplus was 6% on turnover of £33m compared to 5% 22-34 27 in the previous year. Over the year RF achieved a modest growth in turnover of 5.8%, again, 35-44 29 reflecting strong competition for public funds. -

Local Authority (England) Essex County Council Somerset County Council Hertfordshire County Council Islington Social Services B

Local Authority (England) Essex County Council Somerset County Council Hertfordshire County Council Islington Social Services Borough of Lambeth Council Lincolnshire County Council Staffordshire County Council Southampton City Council Northamptonshire County Council Kingston upon Hull City Council East Riding of Yorkshire Council Sunderland City Council Norfolk County Council Kent County Council Middlesbrough Borough Council Lancashire County Council Suffolk County Council Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Merton Leeds City Council Luton Borough Council West Berkshire Council Stoke-on-Trent City Council Central Bedfordshire Council London Borough of Havering London Borough of Brent St Helens Council Warrington Borough Council South Gloucestershire Council Cornwall Council Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council North Tyneside Metropolitan Borough Council Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council Coventry City Council Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council Barnet London Borough Council Cambridgeshire County Council Cheshire East Council Shropshire Council Devon County Council Leicestershire County Council Telford & Wrekin Council Derby City Council Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Kirklees Metropolitan Council Bournemouth Borough Council Nottingham City Council Plymouth City Council Trafford Council Newcastle-upon-Tyne City Council Wigan Council City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Bedford Borough Council Milton Keynes Council Peterborough City Council East -

Council 23 July 2008 Appointments to Outside

COUNCIL 23 JULY 2008 APPOINTMENTS TO OUTSIDE BODIES (Director of Corporate Services – Democratic and Registration Services) 1 PURPOSE OF DECISION 1.1 This report asks the Council to agree appointments to the Joint Group of South Central Health Overview and Scrutiny Committees. 2 RECOMMENDATION 2.1 That two Members of the Council’s Health Overview and Scrutiny Panel are nominated to sit on the Joint Group of South Central Health Overview and Scrutiny Committees. 2.2 That two deputies are appointed, also drawn from the Health Overview and Scrutiny Panel, to substitute if either Member is unable to attend. 3 ADVICE RECEIVED FROM STATUTORY AND OTHER OFFICERS Borough Solicitor 3.1 There are no legal implications arising directly from this report. Borough Treasurer 3.2 The appointees will be entitled to claim travelling expenses to meetings in accordance with the Members' Allowances Scheme at the casual user rate payable to officers. This is unlikely to exceed £100 per annum. 3.3 Hampshire County Council provides the lead administrative support to the Group. Costs associated with this will be shared on an equal basis amongst member authorities. In practice this means the cost of the venue and a buffet lunch when the Council hosts the meeting. These costs will be minimal and can be met from within existing budgets. Equalities Impact Assessment 3.4 Not relevant to this report. Strategic Risk Management Issues 3.5 Not relevant to this report. 4 SUPPORTING INFORMATION 4.1 The Joint Group of South Central Health Overview and Scrutiny Committees