Ecological Impact Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Os Répteis De Angola: História, Diversidade, Endemismo E Hotspots

CAPÍTULO 13 OS RÉPTEIS DE ANGOLA: HISTÓRIA, DIVERSIDADE, ENDEMISMO E HOTSPOTS William R. Branch1,2, Pedro Vaz Pinto3,4, Ninda Baptista1,4,5 e Werner Conradie1,6,7 Resumo O estado actual do conhecimento sobre a diversidade dos répteis de Angola é aqui tratada no contexto da história da investigação herpe‑ tológica no país. A diversidade de répteis é comparada com a diversidade conhecida em regiões adjacentes de modo a permitir esclarecer questões taxonómicas e padrões biogeográficos. No final do século xix, mais de 67% dos répteis angolanos encontravam‑se descritos. Os estudos estag‑ naram durante o século seguinte, mas aumentaram na última década. Actualmente, são conhecidos pelo menos 278 répteis, mas foram feitas numerosas novas descobertas durante levantamentos recentes e muitas espécies novas aguardam descrição. Embora a diversidade dos lagartos e das cobras seja praticamente idêntica, a maioria das novas descobertas verifica‑se nos lagartos, particularmente nas osgas e lacertídeos. Destacam‑ ‑se aqui os répteis angolanos mal conhecidos e outros de regiões adjacentes que possam ocorrer no país. A maioria dos répteis endémicos angolanos é constituída por lagartos e encontra ‑se associada à escarpa e à região árida do Sudoeste. Está em curso a identificação de hotspots de diversidade de 1 National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, South Africa 2 Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P.O. Box 77000, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth 6031, South Africa 3 Fundação Kissama, Rua 60, Casa 560, Lar do Patriota, Luanda, Angola 4 CIBIO ‑InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Laboratório Associado, Campus de Vairão, Universidade do Porto, 4485 ‑661 Vairão, Portugal 5 ISCED, Instituto Superior de Ciências da Educação da Huíla, Rua Sarmento Rodrigues s/n, Lubango, Angola 6 School of Natural Resource Management, George Campus, Nelson Mandela University, George 6530, South Africa 7 Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. -

A Taxonomic Framework for Typhlopid Snakes from the Caribbean and Other Regions (Reptilia, Squamata)

caribbean herpetology article A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata) S. Blair Hedges1,*, Angela B. Marion1, Kelly M. Lipp1,2, Julie Marin3,4, and Nicolas Vidal3 1Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA. 2Current address: School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7450, USA. 3Département Systématique et Evolution, UMR 7138, C.P. 26, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France. 4Current address: Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Article registration: http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:47191405-862B-4FB6-8A28-29AB7E25FBDD Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 17 January 2014. Citation: Hedges SB, Marion AB, Lipp KM, Marin J, Vidal N. 2014. A taxonomic framework for typhlopid snakes from the Caribbean and other regions (Reptilia, Squamata). Caribbean Herpetology 49:1–61. Abstract The evolutionary history and taxonomy of worm-like snakes (scolecophidians) continues to be refined as new molec- ular data are gathered and analyzed. Here we present additional evidence on the phylogeny of these snakes, from morphological data and 489 new DNA sequences, and propose a new taxonomic framework for the family Typhlopi- dae. Of 257 named species of typhlopid snakes, 92 are now placed in molecular phylogenies along with 60 addition- al species yet to be described. Afrotyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed almost exclusively in sub-Saharan Africa and contains three genera: Afrotyphlops, Letheobia, and Rhinotyphlops. Asiatyphlopinae subfam. nov. is distributed in Asia, Australasia, and islands of the western and southern Pacific, and includes ten genera:Acutotyphlops, Anilios, Asiatyphlops gen. -

Herpetological Survey of Iona National Park and Namibe Regional Natural Park, with a Synoptic List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Namibe Province, Southwestern

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301732245 Herpetological Survey of Iona National Park and Namibe Regional Natural Park, with a Synoptic List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Namibe Province, Southwestern .... Article · May 2016 CITATIONS READS 12 1,012 10 authors, including: Luis Miguel Pires Ceríaco Suzana Bandeira University of Porto Villanova University 63 PUBLICATIONS 469 CITATIONS 10 PUBLICATIONS 33 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Edward L Stanley Arianna Kuhn Florida Museum of Natural History American Museum of Natural History 64 PUBLICATIONS 416 CITATIONS 3 PUBLICATIONS 28 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Global Assessment of Reptile Distributions View project Global Reptile Assessment by Species Specialist Group (International) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Luis Miguel Pires Ceríaco on 30 April 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Reprinted frorm Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences , ser. 4, vol. 63, pp. 15-61. © CAS 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Series 4, Volume 63, No. 2, pp. 15–61, 19 figs., Appendix April 29, 2016 Herpetological Survey of Iona National Park and Namibe Regional Natural Park, with a Synoptic List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Namibe Province, Southwestern Angola Luis M. P. Ceríaco 1,2,8 , Sango dos Anjos Carlos de Sá 3, Suzana Bandeira 3, Hilária Valério 3, Edward L. Stanley 2, Arianna L. Kuhn 4,5 , Mariana P. Marques 1, Jens V. Vindum 6, David C. -

Article (Published Version)

Article Identifying the snake: First scoping review on practices of communities and healthcare providers confronted with snakebite across the world BOLON, Isabelle, et al. Abstract Background Snakebite envenoming is a major global health problem that kills or disables half a million people in the world’s poorest countries. Biting snake identification is key to understanding snakebite eco-epidemiology and optimizing its clinical management. The role of snakebite victims and healthcare providers in biting snake identification has not been studied globally. Objective This scoping review aims to identify and characterize the practices in biting snake identification across the globe. Methods Epidemiological studies of snakebite in humans that provide information on biting snake identification were systematically searched in Web of Science and Pubmed from inception to 2nd February 2019. This search was further extended by snowball search, hand searching literature reviews, and using Google Scholar. Two independent reviewers screened publications and charted the data. Results We analysed 150 publications reporting 33,827 snakebite cases across 35 countries. On average 70% of victims/bystanders spotted the snake responsible for the bite and 38% captured/killed it and brought it to the healthcare facility. [...] Reference BOLON, Isabelle, et al. Identifying the snake: First scoping review on practices of communities and healthcare providers confronted with snakebite across the world. PLOS ONE, 2020, vol. 15, no. 3, p. e0229989 PMID : 32134964 DOI : 10.1371/journal.pone.0229989 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:132992 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Identifying the snake: First scoping review on practices of communities and healthcare providers confronted with snakebite across the world 1 1 1 1,2 Isabelle BolonID *, Andrew M. -

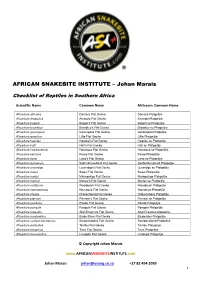

Johan Marais

AFRICAN SNAKEBITE INSTITUTE – Johan Marais Checklist of Reptiles in Southern Africa Scientific Name Common Name Afrikaans Common Name Afroedura africana Damara Flat Gecko Damara Platgeitjie Afroedura amatolica Amatola Flat Gecko Amatola Platgeitjie Afroedura bogerti Bogert's Flat Gecko Bogert se Platgeitjie Afroedura broadleyi Broadley’s Flat Gecko Broadley se Platgeitjie Afroedura gorongosa Gorongosa Flat Gecko Gorongosa Platgeitjie Afroedura granitica Lillie Flat Gecko Lillie Platgeitjie Afroedura haackei Haacke's Flat Gecko Haacke se Platgeitjie Afroedura halli Hall's Flat Gecko Hall se Platgeitjie Afroedura hawequensis Hawequa Flat Gecko Hawequa se Platgeitjie Afroedura karroica Karoo Flat Gecko Karoo Platgeitjie Afroedura langi Lang's Flat Gecko Lang se Platgeitjie Afroedura leoloensis Sekhukhuneland Flat Gecko Sekhukhuneland Platgeitjie Afroedura loveridgei Loveridge's Flat Gecko Loveridge se Platgeitjie Afroedura major Swazi Flat Gecko Swazi Platgeitjie Afroedura maripi Mariepskop Flat Gecko Mariepskop Platgeitjie Afroedura marleyi Marley's Flat Gecko Marley se Platgeitjie Afroedura multiporis Woodbush Flat Gecko Woodbush Platgeijtie Afroedura namaquensis Namaqua Flat Gecko Namakwa Platgeitjie Afroedura nivaria Drakensberg Flat Gecko Drakensberg Platgeitjie Afroedura pienaari Pienaar’s Flat Gecko Pienaar se Platgeitjie Afroedura pondolia Pondo Flat Gecko Pondo Platgeitjie Afroedura pongola Pongola Flat Gecko Pongola Platgeitjie Afroedura rupestris Abel Erasmus Flat Gecko Abel Erasmus platgeitjie Afroedura rondavelica Blyde River -

Patterns of Species Richness, Endemism and Environmental Gradients of African Reptiles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Patterns of species richness, endemism ARTICLE and environmental gradients of African reptiles Amir Lewin1*, Anat Feldman1, Aaron M. Bauer2, Jonathan Belmaker1, Donald G. Broadley3†, Laurent Chirio4, Yuval Itescu1, Matthew LeBreton5, Erez Maza1, Danny Meirte6, Zoltan T. Nagy7, Maria Novosolov1, Uri Roll8, 1 9 1 1 Oliver Tallowin , Jean-Francßois Trape , Enav Vidan and Shai Meiri 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Aim To map and assess the richness patterns of reptiles (and included groups: Biology, Villanova University, Villanova PA 3 amphisbaenians, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles) in Africa, quantify the 19085, USA, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, PO Box 240, Bulawayo, overlap in species richness of reptiles (and included groups) with the other ter- Zimbabwe, 4Museum National d’Histoire restrial vertebrate classes, investigate the environmental correlates underlying Naturelle, Department Systematique et these patterns, and evaluate the role of range size on richness patterns. Evolution (Reptiles), ISYEB (Institut Location Africa. Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 CNRS/EPHE/MNHN), Paris, France, Methods We assembled a data set of distributions of all African reptile spe- 5Mosaic, (Environment, Health, Data, cies. We tested the spatial congruence of reptile richness with that of amphib- Technology), BP 35322 Yaounde, Cameroon, ians, birds and mammals. We further tested the relative importance of 6Department of African Biology, Royal temperature, precipitation, elevation range and net primary productivity for Museum for Central Africa, 3080 Tervuren, species richness over two spatial scales (ecoregions and 1° grids). We arranged Belgium, 7Royal Belgian Institute of Natural reptile and vertebrate groups into range-size quartiles in order to evaluate the Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny, role of range size in producing richness patterns. -

Reproductive Biology and Food Habits of the Blindsnake Liotyphlops Beui (Scolecophidia: Anomalepididae) Author(S): Lilian Parpinelli and Otavio A.V

Reproductive Biology and Food Habits of the Blindsnake Liotyphlops beui (Scolecophidia: Anomalepididae) Author(s): Lilian Parpinelli and Otavio A.V. Marques Source: South American Journal of Herpetology, 10(3):205-210. Published By: Brazilian Society of Herpetology DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2994/SAJH-D-15-00013.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2994/SAJH-D-15-00013.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 10(3), 2015, 205 03 June 2015 25 November 2015 Ana Lucia da Costa Prudente 10.2994/SAJH-D-15-00013.1 South American Journal of Herpetology, 10(3), 2015, 205–210 © 2015 Brazilian Society of Herpetology Reproductive Biology and Food Habits of the Blindsnake Liotyphlops beui (Scolecophidia: Anomalepididae) Lilian Parpinelli1, Otavio A.V. Marques1,* 1 Instituto Butantan, Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução, Avenida Doutor Vital Brazil, 1.500, São Paulo, CEP 05503‑900, SP, Brazil. -

Andrew B. Davies

CURRICULUM VITAE ANDREW B. DAVIES Department of Global Ecology Carnegie Institution for Science 260 Panama St., Stanford CA 94305 [email protected] +1 650 380 0100 EDUCATION 2010-2014 PhD in Zoology, University of Pretoria, South Africa 2008-2010 MSc in Entomology, University of Pretoria, South Africa 2007 BSc Honours (cum laude) in Zoology, University of Pretoria, South Africa. 2004-2006 BSc (cum laude) in Environmental Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2014 – present Postdoctoral Researcher. Department of Global Ecology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford University, USA. Mentor: Gregory P. Asner 2014 Postdoctoral Researcher. Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Mentor: Mark P. Robertson PEER-REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS 1. Muvengwi, J, Parrini, F, Witkowski, ETF & Davies, AB (2018) Are termite mounds always grazing hotspots? Grazing variability with mound size, season and geology in an African savanna. Ecosystems online. 2. Leitner, M, Davies, AB, Parr, CL, Eggleton, P & Robertson, MP (2018) Woody encroachment slows decomposition and termite activity in an African savanna. Global Change Biology 24, 2597-2606. 3. Davies, AB, Gaylard, A & Asner, GP (2018) Megafaunal effects on vegetation structure throughout a densely wooded African landscape. Ecological Applications 28, 398-408. 4. Muvengwi, J, Davies, AB, Parrini, F & Witkowski, ETF (2018) Geology drives the spatial patterning and structure of termite mounds in an African savanna. Ecosphere 9, e02148. 5. Muvengwi, J, Davies, AB, Parrini, F & Witkowski, ETF (2018) Termite diversity is higher in landscapes with lower productivity. Insectes Sociaux 65, 25-35. 6. Davies, AB, Ancrenaz, M, Oram, F & Asner, GP (2017) Canopy structure drives orangutan habitat use in disturbed Bornean forests. -

Zimbabwe Aanstreep Reptilia 9 Study

ZIMBABWE SAFARI: 31/10 - 13/11/2018 Eastern Highlands - Mana Pools N. Park - Matusadona N.Park AMFIBIEËN 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10111213 1 Arthroleptis stenodactylus Common Squeaker 3 Arthroleptis troglodytes ??? Cave Squeaker 2 Arthroleptis xenodactyloides Dwarf Squeaker 4 Sclerophrys fenoulheti Fenoulheti's Toad 5 Sclerophrys garmani Garman's Toad 6 Sclerophrys gutturalis Guttural Toad 7 Sclerophrys inyangae ??? Inyanga Toad 8 Sclerophrys kavangensis ??? Kavango Toad 9 Sclerophrys pusilla Flat-backed Toad 10 Schismaderma carens Red Toad 11 Stephopaedes anotis Chirinda Toad 12 Hemisus guineensis Guinea Snout-burrower 13 Hemisus marmoratus Marbled Snout-burrower 15 Afrixalus brachycnemis ??? Golden Spiny Reed Frog 16 Afrixalus fornasini Fornasini's Spiny Reed Frog 17 Hyperolius argus ??? Argus Reed Frog 18 Hyperolius benguellensis Bocage's Sharp-nosed Reed Frog 19 Hyperolius inyangae Nyanga Long Reed Frog 20 Hyperolius viridiflavus Common Reed Frog 21 Hyperolius nasicus nasutus Sharp-nosed Reed Frog 22 Hyperolius pusillus??? Water Lily Reed Frog 23 Hyperolius acuticeps Slender Reed Frog 24 Hyperolius tuberilinguis Tinker Reed Frog 25 Kassina maculata Red-legged Kassina 26 Kassina senegalensis Senegal Kassina 27 Leptopelis argenteus Silvery Tree Frog 28 Leptopelis bocagii Bocage's Burrowing Tree Frog 29 Leptopelis broadleyi Broadleys' Tree Frog 30 Leptopelis flavomaculatus Yellow-spotted Tree Frog 31 Leptopelis mossambicus Mozambique Tree Frog 32 Breviceps adspersus Common Rain Frog 33 Breviceps mossambicus Mozambique Rain Frog 34 Breviceps -

The Reptiles of Angola: History, Diversity, Endemism and Hotspots

Chapter 13 The Reptiles of Angola: History, Diversity, Endemism and Hotspots William R. Branch, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Ninda Baptista, and Werner Conradie Abstract This review summarises the current status of our knowledge of Angolan reptile diversity, and places it into a historical context of understanding and growth. It is compared and contrasted with known diversity in adjacent regions to allow insight into taxonomic status and biogeographic patterns. Over 67% of Angolan reptiles were described by the end of the nineteenth century. Studies stagnated dur- ing the twentieth century but have increased in the last decade. At least 278 reptiles are currently known, but numerous new discoveries have been made during recent surveys, and many novelties await description. Although lizard and snake diversity is currently almost equal, most new discoveries occur in lizards, particularly geckos and lacertids. Poorly known Angolan reptiles and others from adjacent regions that W. R. Branch (deceased) National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, Hogsback, South Africa Department of Zoology, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] N. Baptista National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, Hogsback, South Africa CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal Instituto Superior de Ciências da Educaҫão da Huíla, Rua Sarmento Rodrigues, Lubango, Angola e-mail: [email protected] W. Conradie (*) National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, Hogsback, South Africa School of Natural Resource Management, Nelson Mandela University, George, South Africa Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), Humewood, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 283 B. -

National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Vol

National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Vol. 7: Genetic Diversity National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 TECHNICAL REPORT Volume 7: Genetic Diversity REPORT NUMBER: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12143/6376 National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Vol. 7: Genetic Diversity CITATION FOR THIS REPORT: Tolley, K.A., da Silva, J.M. & Jansen van Vuuren, B. 2019. South African National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Volume 7: Genetic Diversity. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12143/6376 PREPARED BY: Tolley, K.A., da Silva, J.M., Jansen van Vuuren, B., Bishop, J., Dalton, D., du Plessis, M., Labuschagne, K., Kotze, A., Masehela, T., Mwale, M., Selier. J., Šmíd, J., Suleman, E., Visser, J., & von der Heyden, S. REVIEWER: Sean Hoban CONTACT PERSON: Krystal A. Tolley: [email protected] The NBA 2018 was undertaken primarily during 2015 to early 2019 and therefore the names and acronyms of government departments in existence during that period are used throughout the NBA reports. Please refer to www.gov.za to see that changes in government departments that occurred in mid-2019. 2 National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Vol. 7: Genetic Diversity This report forms part of a set of reports, datasets and supplementary materials that make up the South African National Biodiversity Assessment 2018. Please see the website [http://nba.sanbi.org.za/] for full accessibility to all materials. SYNTHESIS REPORT For reference in scientific publications Skowno, A.L., Poole, C.J., Raimondo, D.C., Sink, K.J., Van Deventer, H., Van Niekerk, L., Harris, L.R., Smith-Adao, L.B., Tolley, K.A., Zengeya, T.A., Foden, W.B., Midgley, G.F. -

Snakes of Angola: an Annotated Checklist 1,2William R

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 12(2) [General Section]: 41–82 (e159). Snakes of Angola: An annotated checklist 1,2William R. Branch 1Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA 2National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project, Wild Bird Trust, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—The first annotated checklist for over 120 years is presented of the snakes of Angola, Africa. It details the snakes currently recorded from Angola (including the Cabinda enclave), and summarizes the literature documenting their description, provenance, and often tortuous taxonomic history. The species are assigned, with comment where appropriate, to higher taxonomic groupings based on modern snake phylogenetic studies, and the need or potential for further studies are noted. In 1895 José Vicente Barboza du Bocage recorded 71 snakes in his monographic treatment of the Angolan herpetofauna, and subsequently Monard (1937) added 10 additional species. This review documents the 122 snakes currently recorded from Angola, and lists a further seven that have been recorded in close proximity to the Angolan border and which can be expected to occur in Angola, albeit marginally. Cryptic diversity identified in taxa such as the Boaedon capensis-fuliginosus-lineatus complex and Philothamnus semivariegatus complex indicate more species can be expected. Relative to southern Africa, the Angolan snake fauna contains a higher proportion of colubrid snakes, enhanced particularly by diverse arboreal species of the Congo Basin. There are relatively few endemic snakes (5.4%), and most inhabit the mesic grasslands of the escarpment and adjacent highlands. None are obviously threatened, although records of the endemic Angolan adder (Bitis heraldica) remain scarce and the species may require directed surveys to assess its conservation status.