The Christian and Not-So Christian Calendar from Christmas to Pentecost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Paul Parish School 2019-2020 EVENTS CALENDAR

St. Paul Parish School 2019-2020 EVENTS CALENDAR Aug 29 Ice Cream Social for all families 6:30-7:30pm Sep 2 Labor Day – No School 3 Orientation Day – Student attendance is required -New Families 9:00-10:00am, Returning Families 10:00am-1:00pm 4 Classes begin (Kindergarten dismisses at noon thru 9/13) 4 Middle School 101, 6:30-7:30pm 6 Mass with Archbishop Sample, 9:00am 9 Star and DIBELS standardized testing through 9/27 16-20 Scholastic Book Fair 17 Curriculum Night for parents, 6:30pm 18 Back to School Mass, 9:00am Oct 8 Lifetouch School Portraits 9 Mass in honor of Our Lady of the Rosary, 9:00am 11 Inservice – No School 31 Halloween Costume Strut Nov 1 All Saints Day Mass, hosted by staff, 9:00am 1 End of 1st Quarter 2 St. Paul Auction 5 Photo Retakes 8 Teacher Professional Development – Noon Dismissal 11 Veterans Day – No School 14 Parent/Teacher Evening Conference, Noon Dismissal 15 Parent/Teacher Conference, No School 25 Box and Label Night for Wreath Sale, 6:30pm 26 Wreath Pick Up Day, Noon-5:00pm 27 Thanksgiving Mass, 9:00am, Noon Dismissal 28 - 29 Thanksgiving Holiday – No School Dec 11 Mass in honor of the Immaculate Conception of Blessed Mary, 9:00am 19 Christmas Program at The Shedd, 6:30pm 20 Christmas Break Begins, Noon dismissal 23 - Jan 5 Christmas Break Jan 6 Classes resume 15 Mass in honor of the Conversion of St. Paul, 9:00am 20 Martin Luther King Jr Holiday – No School 24 End of 2nd quarter / Noon Dismissal / Teacher Professional Development 26 Open House, 11:30am – 1:30pm 27-31 Catholic Schools Week 30 CSW Mass at Marist High School, 9:00am 31 Archdiocese Teachers’ Faith Formation Inservice – No School Feb 14,15,16 Annual St. -

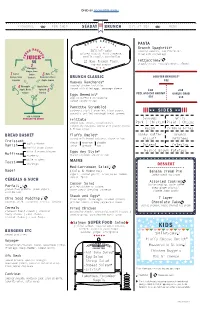

Seaday Brunch Menu

Grab an accessible menu. CARNIVAL FUN SHIP SEADAY BRUNCH DAY AT SEA MENU S E S P E C O U I A H L PASTA Brunch Spaghetti* P R E H S Skillet-cake roasted tomatoes, ham florentine, S S E E whipped ricotta, fruit preserve, fried soft boiled egg R D vanilla crumble, marshmallow F JUICE N $5 12 Hour French Toast Fettuccine S roasted peaches arugula pesto, roasted peppers, almonds Pineapple2 Ginger, Lime 1 Carrot Dates 3 Kale Orange, Lime Turmeric Romaine Lettuce BRUNCH CLASSIC LOBSTER BENEDICT* Cayenne Apple, Lemon $12 Huevos Rancheros* Pineapple Apple, Kale roasted chicken tortillas, 4 topped with fried eggs, manchego cheese Apple, Beets Spinach 1 LB 2 LB Ginger Parsley 5 Eggs Benedict* PEEL AND EAT SHRIMP GARLIC CRAB english muffin & hollandaise $10 $15 smoked salmon or ham Pancetta Scrambled carbonara style | pecorino, black pepper, SIDES pancetta, grilled sourdough bread, greens 100 % VEGAN PRESSED TO ORDER Frittata Sausage Grits smoked ham, chives, cream cheese, Pork | Chicken Plain | Cheese fingerling potatoes,topped with pickle onions & frisee salad Bacon Crinkle Fries BREAD BASKET Fluffy Omelet* Honey Butter Brunch served with brunch potatoes, bacon or ham Biscuit Potatoes Croissant apple cinnamon tomato mushroom cheddar Danish onion spinach ham Oatmeal Coleslaw vanilla cream cheese olive & orange blossom Eggs Any Style Hashed Brown Potatoes Muffins * blueberry brunch potatoes, bacon or ham white or wheat MAINS Toast sourdough N DESSERT Mediterranean Salad S Bagel (Kale & Romaine) Banana Cream Pie yogurt, roasted garlic, olive puree, -

Eastertide Spring Pentecost

Lampstand The newsletter of “You are the light of the world. A city build on a hill cannot be hid. No one after lighting a lamp puts it under a bushel basket, but on The Lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house. “ Eastertide Spring Pentecost www.stjohnsniantic.org 860-739-2324 Saint John’s Returning to Regular Sunday Practices Governor Ned Lamont Eases Covid Restrictions Beginning May 19 As announced this week Governor Ned Lamont will lift or modify all remaining Covid 19 restrictions on May 19th. Indoor mask wearing will continue. St. John’s will return to including hymn singing and administering Holy Communion in both consecrated elements of bread and wine. We will continue to offer printed prayers for Spiritual Communion. Seating capacity limits have already been eased. Saint John’s Christian Education Program Saint John’s Church School Director of Youth & Education Faithe Emerich will continue offering virtual church school programming via Zoom for the remainder of this Program Year. The Program Year will end on Sunday, June 20th, the day we have set aside for Youth Sunday. Youth Sunday will be celebrated virtually, just as we did in 2020. Tuesday Women’s Bible/Book Group St. John’s Tuesday Women’s Group will continue to meet virtually on Zoom for now and may eventually meet outdoors as weather permits in the future. No decision has been made on moving back indoors. Right now SSKP will continue to occupy space in the Parish Hall, operating as a “Drive Thru Pantry”. Saturday Morning “Coffee with Matthew, Mark, Luke and John” St. -

CARNIVAL, LENT and HOLY WEEK TRADITIONS (3) HOLY WEEK FAITH and TRADITION the Holy Week Opens on Palm Sunday and Culminates on Easter Sunday

CARNIVAL, LENT AND HOLY WEEK TRADITIONS (3) HOLY WEEK FAITH AND TRADITION The Holy Week opens on Palm Sunday and culminates on Easter Sunday. During these eight days, the marathon of religious celebrations, artistic exhibitions and pious manisfestations fuse together faith and popular traditions. PALM SUNDAY Palm Sunday commemorates Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Short processions are held from small chapels to the parish church, while olive and palm branches are blessed. Participants GOOD FRIDAY take the blessed cuttings home as a means Good Friday commemorates the crucifixion and of protection. death of Christ. As a sign of mourning, flags are lowered half mast, while the ringing of bells is replaced by the rattling of a large wooden drum called ‘ċuqlajta’. The devotion of the seven visits persists throughout the morning. No Holy Masses are celebrated on the day. Instead, a liturgical function is celebrated in the afternoon. Processions with life-size effigies are organized in twelve localities in Malta and four in Gozo. In two localities in Malta and another two in Gozo, this procession takes place in the preceding days. HOLY SATURDAY MAUNDY THURSDAY The celebration of the Easter Maundy Thursday triggers the Easter Triduum. The only Holy Mass held in Vigil opens with the blessing the morning is lead by the Diocesan Bishop and entails the blessing of the of fire and the lighting up sacred oils. The evening Holy Mass commemorates the Last Supper and of the paschal candle, features the ceremony of the Washing of the Feet. Afterwards, the Blessed popularly referred to Sacrament is placed in the specially set up Altar of as ‘Blandun’. -

LENT the Season of Lent

LENT Following is the invitation to the observance of a holy Lent as stated in the Book of Common Prayer, pages 264-265: Dear People of God: The first Christians observed with great devotion the days of our Lord's passion and resurrection, and it became the custom of the Church to prepare for them by a season of penitence and fasting. This season of Lent provided a time in which converts to the faith were prepared for Holy Baptism. It was also a time when those who, because of notorious sins, had been separated from the body of the faithful were reconciled by penitence and forgiveness, and restored to the fellowship of the Church. Thereby, the whole congregation was put in mind of the message of pardon and absolution set forth in the Gospel of our Savior, and of the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith. I invite you, therefore, in the name of the Church, to the observance of a holy Lent, by self-examination and repentance; by prayer, fasting, and self-denial; and by reading and meditating on God's holy Word. And, to make a right beginning of repentance, and as a mark of our mortal nature, let us now kneel before the Lord, our maker and redeemer. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Below is an explanatory essay on the Season of Lent by Dennis Bratcher. The Season of Lent Lent Carnival/Mardi Gras Ash Wednesday The Journey of Lent Reflections on Lent The season of Lent has not been well observed in much of evangelical Christianity, largely because it was associated with "high church" liturgical worship that some churches were eager to reject. -

Lancaster St. Mary Church Begins Yearlong Bicentennial Celebration

CatholicThe TIMES The Diocese of Columbus’ News Source August 11, 2019 • 19TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME • Volume 68:38 Inside this issue Happy anniversary: Portsmouth St. Mary begins a 150th anniversary celebration next month with its festival and a Mass on Sept. 15, Page 3 Bright light lost: Incoming DeSales High School freshman and St. James the Less School graduate Xavier Quinn, 14, was fatally shot on July 26, Page 13 Faith and festivals: Summer parish festivals are sort of a last hurrah before the start of the school year, and in some cases have sparked a conversion to the Catholic faith, Pages 18-20 LANCASTER ST. MARY CHURCH BEGINS YEARLONG BICENTENNIAL CELEBRATION Pages 10-11 Catholic Times 2 August 11, 2019 Editor’s reflections by Doug Bean Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary: Hope in hard times On Thursday, newest of the four Marian dogmas nity, should have a first-tier respect holy womb where seeds are planted, Aug. 15, the recognized by the Church. Pope Pius even though all the truths about Our but it takes time for them to grow,” Church honors XII’s elevation of the Assumption as Lady are going to be subordinate Miravalle said. the Blessed Virgin dogma, which is considered a bind- to Jesus. But it’s a key connector “At Vatican I back in 1870, there Mary with a spe- ing truth divinely revealed by God, between us and Jesus, and that’s why were 50 petitions asking for this, and cial day marking came just 69 years ago. On Nov. 1, the Marian feasts are so important.” the Church said ‘No, give it a little her glorious Assumption into heaven. -

Easter Egg Hunt & Carnival Vision

Non-Profit Organization LOVE GOD U.S. Postage Paid Permit No. 318 the LOVE ONE ANOTHER LOVE THE WORLD Vision First Baptist Church of Shallotte 4486 Main Street Shallotte, NC 28470 Phone 910.754.4048 Fax 910.754.2642 www.fbcshallotte.org April 2017 Office Hours: M-F 9am—3pm Early Celebration Service 8:30am Sunday School 9:45am Morning Worship 11:00am Celebrate Easter With Us Evening Worship 6:00pm Wednesday 6:30pm SONrise Service Sunday School Celebration Service DAILY BIBLE READING PLAN at 7 AM at 9:45 AM at 11 AM Breakfast Graciously Provided OLD TESTAMENT / NEW TESTAMENT by Men’s Ministry No 8:30 or evening worship services Apr-1 Judges 13-15 Apr-17 2 Samuel 1-2; Luke 14 Apr-2 Judges 16-18; Luke 7 Apr-18 2 Samuel 3-5 Apr-3 Judges 19-21 Apr-19 2 Samuel 6-8 Apr-4 Ruth Apr-20 2 Samuel 9-11; Luke 15 & carnival Apr-5 1 Samuel 1-3; Luke 8 Apr-21 2 Samuel 12-13; Luke 16 Easter Egg Hunt Apr-6 1 Samuel 4-7 Apr-22 2 Samuel 14-15; Luke 17 Apr-7 1 Samuel 8-10 Apr-23 2 Samuel 16-18 Apr-8 1 Samuel 11-12; Luke 9 Apr-24 2 Samuel 19-20; Luke 18 Apr-9 1 Samuel 13-14 Apr-25 2 Samuel 21-22 Apr-10 1 Samuel 15-16; Luke 10 Apr-26 2 Samuel 23-24; Luke 19 Apr-11 1 Samuel 17-18; Luke 11 Apr-27 1 Kings 1-2 Apr-12 1 Samuel 19-21 Apr-28 1 Kings 3-5; Luke 20 Apr-13 1 Samuel 22-24 Apr-29 1 Kings 6-7 Apr-14 1 Samuel 25-26; Luke 12 Apr-30 1 Kings 8-9 Apr-15 1 Samuel 27-29 Candy donations may be placed in the container in the foyer. -

Carnival Season

Italy where people paraded and danced or parade, which has elements of a cir- at masquerade balls. They wore masks cus. Festivalgoers often wear masks and Geography to hide their identities and therefore so- elaborate costumes, sacrifi cing sleep for In The cial classes, so that all could share in the all-night parties. celebration. Venice hosted an extremely Carnival celebrations evolved differ- News™ famous carnival that began in 1268 and ently depending upon the culture of the today sees 30,000 visitors a year to the cel- area. Rio Carnival dates back to 1723 and ebration. is the largest in the world. There, one pur- Carnival traditions spread from Italy pose of the celebration is for samba schools Neal Lineback to Catholic communities in France, Spain to compete against one another in parade and Mandy Lineback Gritzner and Portugal. France gave the fi nal day of demonstrations. The samba is a popular carnival its modern name “Mardi Gras,” dance that African slaves brought to Bra- which means “Fat Tuesday” in French. zil. Each samba school spends months CARNIVAL Fat Tuesday refers to the Tuesday before building expensive, elaborate fl oats and Ash Wednesday, the day Lent begins and costumes in their pursuit to be the best SEASON most celebrations end. Fat Tuesday is the group. Each group has a band and may Rio de Janeiro hosts one of the largest biggest day of celebration in New Orleans’ have as many as eight fl oats and thou- carnival celebrations in the world. Unfor- Mardi Gras. sands of participants, including dancers tunately, a huge fi re swept through the Rio From France, carnival traditions spread and fl oat riders. -

Popes in History

popes in history medals by Ľudmila Cvengrošová text by Mons . Viliam Judák Dear friends, Despite of having long-term experience in publishing in other areas, through the AXIS MEDIA company I have for the first time entered the environment of medal production. There have been several reasons for this decision. The topic going beyond the borders of not only Slovakia but the ones of Europe as well. The genuine work of the academic sculptress Ľudmila Cvengrošová, an admirable and nice artist. The fine text by the Bishop Viliam Judák. The “Popes in history” edition in this range is a unique work in the world. It proves our potential to offer a work eliminating borders through its mission. Literally and metaphorically, too. The fabulous processing of noble metals and miniatures produced with the smallest details possible will for sure attract the interest of antiquarians but also of those interested in this topic. Although this is a limited edition I am convinced that it will be provided to everybody who wants to commemorate significant part of the historical continuity and Christian civilization. I am pleased to have become part of this unique project, and I believe that whether the medals or this lovely book will present a good message on us in the world and on the world in us. Ján KOVÁČIK AXIS MEDIA 11 Celebrities grown in the artist’s hands There is one thing we always know for sure – that by having set a target for himself/herself an artist actually opens a wonderful world of invention and creativity. In the recent years the academic sculptress and medal maker Ľudmila Cvengrošová has devoted herself to marvellous group projects including a precious cycle of male and female monarchs of the House of Habsburg crowned at the St. -

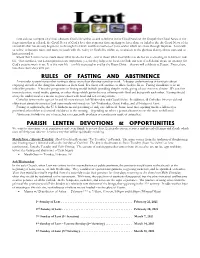

Rules of Fasting and Abstinence Parish Lenten Devotions & Opportunities

Lent calls us to repent of all that obscures God’s life within us and to believe in the Good News of the Gospel: the Good News of the forgiveness that is offered, the Good News of God’s love that is greater than anything we have done or failed to do, the Good News of the eternal life that has already begun for us through the Death and Resurrection of Jesus and in which we share through Baptism. Lent calls us to life: to become more and more in touch with the reality of God’s life within us, to awaken to the glorious destiny that is ours and to hasten toward it. Know that Lent is not so much about what we do for God…as it is about what God wishes to do for us: re-creating us in his love and life. Our sacrifices, our Lenten practices are important, yes, for they help us to focus on God; our acts of self-denial create an opening for God’s creative work in us. It is this new life—our life recreated in and by the Risen Christ—that we will celebrate at Easter. Enter, then, into these forty days with joy. RULES OF FASTING AND ABSTINENCE A reminder to parishioners that fasting is about more than denying ourselves food. A deeper understanding of fasting is about emptying oneself of the thing that distracts us from God. It’s about self-sacrifice to allow God to fill us. Fasting should never be an unhealthy practice. A broader perspective of fasting would include providing simpler meals, giving of our excess to charity. -

1 Church History I: the Early Papacy (C. 64 – 452 AD) “And I Tell Y

Church History I: The Early Papacy (c. 64 – 452 AD) “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” (Matt. 16:18-19 NRSV) Milestones on the Development of the Papacy c. 64 – Peter and Paul were mostly likely martyred at Rome in this year during a short burst of persecution against Christians under the Emperor Nero following a devastating fire in the capital. According to tradition, Peter had also been bishop of Antioch before coming to Rome and after leaving Jerusalem. c. 96 – Clement of Rome intervened in a dispute in a surviving letter to the church at Corinth, which we know as I Clement. Some Corinthian presbyters had been deposed and Clement reminded the congregation that the apostles “appointed bishops and deacons in every place” and it was these appointees who gave directions as to how the ministry was to continue. c. 190 – Pope Victor I ordered synods to be held throughout Christendom to bring the date for the observance of Easter into line with Roman custom. He was not successful. The title pope, derived from the Latin and Greek words for father, was used for the occupants of several of the major episcopal sees throughout the empire in this period, such as Alexandria and Antioch as well as Rome. -

The Popes: a History Free

FREE THE POPES: A HISTORY PDF John Julius Norwich | 528 pages | 04 May 2012 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099565871 | English | London, United Kingdom Shane MacGowan and The Popes - Wikipedia Sincethe pope has official residence in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican Citya city-state enclaved within Rome, Italy. While his office is called the papacy The Popes: A History, the jurisdiction of the episcopal see is called the Holy See. The Holy See is recognized by its adherence at various levels to The Popes: A History organization and by means of its diplomatic relations and political accords with many independent states. According to Catholic traditionthe apostolic see [9] of Rome was founded by Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the 1st century. The papacy is one of the most enduring institutions in the world and has had a prominent part in world history. In some periods of history, the papacy, which originally had no temporal powersaccrued wide secular powers rivaling those of temporal rulers. However, in recent centuries the temporal authority of the papacy has declined and the office is now almost exclusively focused on religious matters. In the early centuries of Christianitythis title was applied, especially in the east, to all bishops [21] and other senior clergy, and later became reserved in the west to the bishop of Rome, a reservation made official only in the 11th century. The Catholic Church teaches that the pastoral office, the office of shepherding the The Popes: A History, that was held by the apostles, as a group or "college" with Saint Peter The Popes: A History their head, is now held by their successors, the bishops, with the bishop of Rome the pope as their head.