The Truth About Mardi Gras Epiphany, Ash Wednesday, and Lent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Paul Parish School 2019-2020 EVENTS CALENDAR

St. Paul Parish School 2019-2020 EVENTS CALENDAR Aug 29 Ice Cream Social for all families 6:30-7:30pm Sep 2 Labor Day – No School 3 Orientation Day – Student attendance is required -New Families 9:00-10:00am, Returning Families 10:00am-1:00pm 4 Classes begin (Kindergarten dismisses at noon thru 9/13) 4 Middle School 101, 6:30-7:30pm 6 Mass with Archbishop Sample, 9:00am 9 Star and DIBELS standardized testing through 9/27 16-20 Scholastic Book Fair 17 Curriculum Night for parents, 6:30pm 18 Back to School Mass, 9:00am Oct 8 Lifetouch School Portraits 9 Mass in honor of Our Lady of the Rosary, 9:00am 11 Inservice – No School 31 Halloween Costume Strut Nov 1 All Saints Day Mass, hosted by staff, 9:00am 1 End of 1st Quarter 2 St. Paul Auction 5 Photo Retakes 8 Teacher Professional Development – Noon Dismissal 11 Veterans Day – No School 14 Parent/Teacher Evening Conference, Noon Dismissal 15 Parent/Teacher Conference, No School 25 Box and Label Night for Wreath Sale, 6:30pm 26 Wreath Pick Up Day, Noon-5:00pm 27 Thanksgiving Mass, 9:00am, Noon Dismissal 28 - 29 Thanksgiving Holiday – No School Dec 11 Mass in honor of the Immaculate Conception of Blessed Mary, 9:00am 19 Christmas Program at The Shedd, 6:30pm 20 Christmas Break Begins, Noon dismissal 23 - Jan 5 Christmas Break Jan 6 Classes resume 15 Mass in honor of the Conversion of St. Paul, 9:00am 20 Martin Luther King Jr Holiday – No School 24 End of 2nd quarter / Noon Dismissal / Teacher Professional Development 26 Open House, 11:30am – 1:30pm 27-31 Catholic Schools Week 30 CSW Mass at Marist High School, 9:00am 31 Archdiocese Teachers’ Faith Formation Inservice – No School Feb 14,15,16 Annual St. -

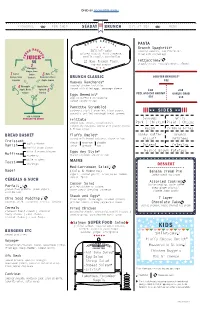

Seaday Brunch Menu

Grab an accessible menu. CARNIVAL FUN SHIP SEADAY BRUNCH DAY AT SEA MENU S E S P E C O U I A H L PASTA Brunch Spaghetti* P R E H S Skillet-cake roasted tomatoes, ham florentine, S S E E whipped ricotta, fruit preserve, fried soft boiled egg R D vanilla crumble, marshmallow F JUICE N $5 12 Hour French Toast Fettuccine S roasted peaches arugula pesto, roasted peppers, almonds Pineapple2 Ginger, Lime 1 Carrot Dates 3 Kale Orange, Lime Turmeric Romaine Lettuce BRUNCH CLASSIC LOBSTER BENEDICT* Cayenne Apple, Lemon $12 Huevos Rancheros* Pineapple Apple, Kale roasted chicken tortillas, 4 topped with fried eggs, manchego cheese Apple, Beets Spinach 1 LB 2 LB Ginger Parsley 5 Eggs Benedict* PEEL AND EAT SHRIMP GARLIC CRAB english muffin & hollandaise $10 $15 smoked salmon or ham Pancetta Scrambled carbonara style | pecorino, black pepper, SIDES pancetta, grilled sourdough bread, greens 100 % VEGAN PRESSED TO ORDER Frittata Sausage Grits smoked ham, chives, cream cheese, Pork | Chicken Plain | Cheese fingerling potatoes,topped with pickle onions & frisee salad Bacon Crinkle Fries BREAD BASKET Fluffy Omelet* Honey Butter Brunch served with brunch potatoes, bacon or ham Biscuit Potatoes Croissant apple cinnamon tomato mushroom cheddar Danish onion spinach ham Oatmeal Coleslaw vanilla cream cheese olive & orange blossom Eggs Any Style Hashed Brown Potatoes Muffins * blueberry brunch potatoes, bacon or ham white or wheat MAINS Toast sourdough N DESSERT Mediterranean Salad S Bagel (Kale & Romaine) Banana Cream Pie yogurt, roasted garlic, olive puree, -

Eastertide Spring Pentecost

Lampstand The newsletter of “You are the light of the world. A city build on a hill cannot be hid. No one after lighting a lamp puts it under a bushel basket, but on The Lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house. “ Eastertide Spring Pentecost www.stjohnsniantic.org 860-739-2324 Saint John’s Returning to Regular Sunday Practices Governor Ned Lamont Eases Covid Restrictions Beginning May 19 As announced this week Governor Ned Lamont will lift or modify all remaining Covid 19 restrictions on May 19th. Indoor mask wearing will continue. St. John’s will return to including hymn singing and administering Holy Communion in both consecrated elements of bread and wine. We will continue to offer printed prayers for Spiritual Communion. Seating capacity limits have already been eased. Saint John’s Christian Education Program Saint John’s Church School Director of Youth & Education Faithe Emerich will continue offering virtual church school programming via Zoom for the remainder of this Program Year. The Program Year will end on Sunday, June 20th, the day we have set aside for Youth Sunday. Youth Sunday will be celebrated virtually, just as we did in 2020. Tuesday Women’s Bible/Book Group St. John’s Tuesday Women’s Group will continue to meet virtually on Zoom for now and may eventually meet outdoors as weather permits in the future. No decision has been made on moving back indoors. Right now SSKP will continue to occupy space in the Parish Hall, operating as a “Drive Thru Pantry”. Saturday Morning “Coffee with Matthew, Mark, Luke and John” St. -

CARNIVAL, LENT and HOLY WEEK TRADITIONS (3) HOLY WEEK FAITH and TRADITION the Holy Week Opens on Palm Sunday and Culminates on Easter Sunday

CARNIVAL, LENT AND HOLY WEEK TRADITIONS (3) HOLY WEEK FAITH AND TRADITION The Holy Week opens on Palm Sunday and culminates on Easter Sunday. During these eight days, the marathon of religious celebrations, artistic exhibitions and pious manisfestations fuse together faith and popular traditions. PALM SUNDAY Palm Sunday commemorates Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Short processions are held from small chapels to the parish church, while olive and palm branches are blessed. Participants GOOD FRIDAY take the blessed cuttings home as a means Good Friday commemorates the crucifixion and of protection. death of Christ. As a sign of mourning, flags are lowered half mast, while the ringing of bells is replaced by the rattling of a large wooden drum called ‘ċuqlajta’. The devotion of the seven visits persists throughout the morning. No Holy Masses are celebrated on the day. Instead, a liturgical function is celebrated in the afternoon. Processions with life-size effigies are organized in twelve localities in Malta and four in Gozo. In two localities in Malta and another two in Gozo, this procession takes place in the preceding days. HOLY SATURDAY MAUNDY THURSDAY The celebration of the Easter Maundy Thursday triggers the Easter Triduum. The only Holy Mass held in Vigil opens with the blessing the morning is lead by the Diocesan Bishop and entails the blessing of the of fire and the lighting up sacred oils. The evening Holy Mass commemorates the Last Supper and of the paschal candle, features the ceremony of the Washing of the Feet. Afterwards, the Blessed popularly referred to Sacrament is placed in the specially set up Altar of as ‘Blandun’. -

LENT the Season of Lent

LENT Following is the invitation to the observance of a holy Lent as stated in the Book of Common Prayer, pages 264-265: Dear People of God: The first Christians observed with great devotion the days of our Lord's passion and resurrection, and it became the custom of the Church to prepare for them by a season of penitence and fasting. This season of Lent provided a time in which converts to the faith were prepared for Holy Baptism. It was also a time when those who, because of notorious sins, had been separated from the body of the faithful were reconciled by penitence and forgiveness, and restored to the fellowship of the Church. Thereby, the whole congregation was put in mind of the message of pardon and absolution set forth in the Gospel of our Savior, and of the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith. I invite you, therefore, in the name of the Church, to the observance of a holy Lent, by self-examination and repentance; by prayer, fasting, and self-denial; and by reading and meditating on God's holy Word. And, to make a right beginning of repentance, and as a mark of our mortal nature, let us now kneel before the Lord, our maker and redeemer. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Below is an explanatory essay on the Season of Lent by Dennis Bratcher. The Season of Lent Lent Carnival/Mardi Gras Ash Wednesday The Journey of Lent Reflections on Lent The season of Lent has not been well observed in much of evangelical Christianity, largely because it was associated with "high church" liturgical worship that some churches were eager to reject. -

Lancaster St. Mary Church Begins Yearlong Bicentennial Celebration

CatholicThe TIMES The Diocese of Columbus’ News Source August 11, 2019 • 19TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME • Volume 68:38 Inside this issue Happy anniversary: Portsmouth St. Mary begins a 150th anniversary celebration next month with its festival and a Mass on Sept. 15, Page 3 Bright light lost: Incoming DeSales High School freshman and St. James the Less School graduate Xavier Quinn, 14, was fatally shot on July 26, Page 13 Faith and festivals: Summer parish festivals are sort of a last hurrah before the start of the school year, and in some cases have sparked a conversion to the Catholic faith, Pages 18-20 LANCASTER ST. MARY CHURCH BEGINS YEARLONG BICENTENNIAL CELEBRATION Pages 10-11 Catholic Times 2 August 11, 2019 Editor’s reflections by Doug Bean Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary: Hope in hard times On Thursday, newest of the four Marian dogmas nity, should have a first-tier respect holy womb where seeds are planted, Aug. 15, the recognized by the Church. Pope Pius even though all the truths about Our but it takes time for them to grow,” Church honors XII’s elevation of the Assumption as Lady are going to be subordinate Miravalle said. the Blessed Virgin dogma, which is considered a bind- to Jesus. But it’s a key connector “At Vatican I back in 1870, there Mary with a spe- ing truth divinely revealed by God, between us and Jesus, and that’s why were 50 petitions asking for this, and cial day marking came just 69 years ago. On Nov. 1, the Marian feasts are so important.” the Church said ‘No, give it a little her glorious Assumption into heaven. -

Easter Egg Hunt & Carnival Vision

Non-Profit Organization LOVE GOD U.S. Postage Paid Permit No. 318 the LOVE ONE ANOTHER LOVE THE WORLD Vision First Baptist Church of Shallotte 4486 Main Street Shallotte, NC 28470 Phone 910.754.4048 Fax 910.754.2642 www.fbcshallotte.org April 2017 Office Hours: M-F 9am—3pm Early Celebration Service 8:30am Sunday School 9:45am Morning Worship 11:00am Celebrate Easter With Us Evening Worship 6:00pm Wednesday 6:30pm SONrise Service Sunday School Celebration Service DAILY BIBLE READING PLAN at 7 AM at 9:45 AM at 11 AM Breakfast Graciously Provided OLD TESTAMENT / NEW TESTAMENT by Men’s Ministry No 8:30 or evening worship services Apr-1 Judges 13-15 Apr-17 2 Samuel 1-2; Luke 14 Apr-2 Judges 16-18; Luke 7 Apr-18 2 Samuel 3-5 Apr-3 Judges 19-21 Apr-19 2 Samuel 6-8 Apr-4 Ruth Apr-20 2 Samuel 9-11; Luke 15 & carnival Apr-5 1 Samuel 1-3; Luke 8 Apr-21 2 Samuel 12-13; Luke 16 Easter Egg Hunt Apr-6 1 Samuel 4-7 Apr-22 2 Samuel 14-15; Luke 17 Apr-7 1 Samuel 8-10 Apr-23 2 Samuel 16-18 Apr-8 1 Samuel 11-12; Luke 9 Apr-24 2 Samuel 19-20; Luke 18 Apr-9 1 Samuel 13-14 Apr-25 2 Samuel 21-22 Apr-10 1 Samuel 15-16; Luke 10 Apr-26 2 Samuel 23-24; Luke 19 Apr-11 1 Samuel 17-18; Luke 11 Apr-27 1 Kings 1-2 Apr-12 1 Samuel 19-21 Apr-28 1 Kings 3-5; Luke 20 Apr-13 1 Samuel 22-24 Apr-29 1 Kings 6-7 Apr-14 1 Samuel 25-26; Luke 12 Apr-30 1 Kings 8-9 Apr-15 1 Samuel 27-29 Candy donations may be placed in the container in the foyer. -

• Mardi Gras Began Over a Thousand Years Ago As a Christian

Mardi Gras began over a thousand years ago as a Christian interpretation of an ancient Roman celebration. This celebration was called Lupercelia and was a circus-like festival held in mid-February. Oddly enough, the name is derived from the Latin word 'lupus' but the meaning as applied to the festival has become obscured over time. The celebration came to America in 1699 when a French explorer set up camp on Fat Tuesday just south of New Orleans. He named the location, Point du Mardi Gras. Mardi Gras was celebrated by masked individuals on carriages and at balls in New Orleans until it was banned for many years while under Spanish rule. Mardi Gras was legitimized by Mistick Krewe of Comus in 1857 which established many of the key features of modern Mardi Gras including unifying themes, secrecy, and a ball after a parade. The Mardi Gras colors were established by the Grand Duke Alexis Romanoff of Russia. The Krewe of Rex appointed him to be the first King of Carnival while he was visiting New Orleans in 1872. The colors of Mardi Gras represent justice (purple), faith (green) and power (gold). After chosen, New Orleans stores stocked up on these colors. LSU chose yellow and purple to be their official colors and pur- chased large quantities of the available cloth. The shops were left with only green cloth, and Tulane University, a rival of LSU's, purchased the remaining cloth and adopted it as their official school color. In spite of the media perception of Mardi Gras by much of the nation, Mardi Gras is largely a family affair. -

2021 Client Outreach Opportunities

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT | FOR YOUR BUSINESS 2021 Client Outreach Opportunities MAXIMIZE RELATIONSHIPS. INCREASE ENGAGEMENT. In a constantly evolving financial services landscape – where a sea of financial guidance and options are a click away – advisors are faced with the challenge of demonstrating their value to clients in a manner that goes beyond product and performance. By making relationship- building a regular part of your business model, you can solidify your commitment to your clients and differentiate yourself from other advisors. There are actionable and timely opportunities throughout the year that make it easy to reach out and create lasting, productive client relationships – even during the unprecedented times of COVID-19. The 2021 Client Outreach Calendar now includes Financial Education event menus created by New York Life Investments to Health & Fitness help you plan your next client event. We have created Mixology & Tastings a menu of different topics and events that cover the Sports themes on the right. Please click on any of the themes ESG on the left-hand side of the inside pages to open these Client Appreciation event menus and plan your next client event! Seasonal & Holiday Charity/Philantrophy FOR REGISTERED REPRESENTATIVE USE ONLY. NOT FOR USE WITH THE GENERAL PUBLIC. Quarter 1 | 2021 Maximize relationships. Increase engagement. PLEASE CLICK ON ANY OF THE THEMES ON THE LEFT-HAND SIDE OF THE PAGE TO OPEN THESE EVENTS January February March Financial National Mentoring Month Senior Independence Month Credit Education -

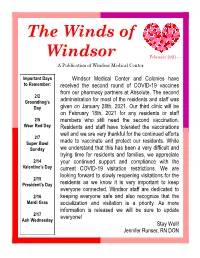

The Winds of Windsor

The Winds of Windsor February 2021 A Publication of Windsor Medical Center Important Days Windsor Medical Center and Colonies have to Remember: received the second round of COVID-19 vaccines from our pharmacy partners at Absolute. The second 2/2 Groundhog’s administration for most of the residents and staff was Day given on January 28th, 2021. Our third clinic will be on February 18th, 2021 for any residents or staff 2/5 members who still need the second vaccination. Wear Red Day Residents and staff have tolerated the vaccinations well and we are very thankful for the continued efforts 2/7 Super Bowl made to vaccinate and protect our residents. While Sunday we understand that this has been a very difficult and trying time for residents and families, we appreciate 2/14 your continued support and compliance with the Valentine’s Day current COVID-19 visitation restrictions. We are looking forward to slowly reopening visitations for the 2/15 President’s Day residents as we know it is very important to keep everyone connected. Windsor staff are dedicated to 2/16 keeping everyone safe and also recognize that the Mardi Gras socialization and visitation is a priority. As more information is released we will be sure to update 2/17 everyone! Ash Wednesday Stay Well! Jennifer Runser, RN DON -Mardi Gras means “Fat Tuesday” in French. -With Ash Wednesday marking the beginning of Lent, a 40 day period of fasting before Easter, Mardi Gras is the "last hurrah" of sorts, with participants indulging in their favorite fatty foods and drinks before giving them up. -

Carnival Season

Italy where people paraded and danced or parade, which has elements of a cir- at masquerade balls. They wore masks cus. Festivalgoers often wear masks and Geography to hide their identities and therefore so- elaborate costumes, sacrifi cing sleep for In The cial classes, so that all could share in the all-night parties. celebration. Venice hosted an extremely Carnival celebrations evolved differ- News™ famous carnival that began in 1268 and ently depending upon the culture of the today sees 30,000 visitors a year to the cel- area. Rio Carnival dates back to 1723 and ebration. is the largest in the world. There, one pur- Carnival traditions spread from Italy pose of the celebration is for samba schools Neal Lineback to Catholic communities in France, Spain to compete against one another in parade and Mandy Lineback Gritzner and Portugal. France gave the fi nal day of demonstrations. The samba is a popular carnival its modern name “Mardi Gras,” dance that African slaves brought to Bra- which means “Fat Tuesday” in French. zil. Each samba school spends months CARNIVAL Fat Tuesday refers to the Tuesday before building expensive, elaborate fl oats and Ash Wednesday, the day Lent begins and costumes in their pursuit to be the best SEASON most celebrations end. Fat Tuesday is the group. Each group has a band and may Rio de Janeiro hosts one of the largest biggest day of celebration in New Orleans’ have as many as eight fl oats and thou- carnival celebrations in the world. Unfor- Mardi Gras. sands of participants, including dancers tunately, a huge fi re swept through the Rio From France, carnival traditions spread and fl oat riders. -

December 9, 2018 Second Sunday of Advent

WHERE THE UPPER EAST SIDE AND EAST HARLEM MEET 135 East 96th Street, New York, NY 10128 212-289-0425 DECEMBER 9, 2018 SECOND SUNDAY OF ADVENT OFFICE HOURS MASS TIMES CHURCH HOURS MON - WED SATURDAYS WEEKDAYS 9am - 8pm 5pm Vigil / 4:30 Confession 8am - 4pm THURS & FRI WEEKENDS SUNDAYS 9am - 5pm 8:30am - 4pm 9am / 11am / 12:30 Spanish MON, TUES, THURS, FRI 8:30am Mass WEDNESDAYS Morning Prayer 8:30am OUR MISSION NUESTRA MISIÓN Taking Jesus’ message of loving service to heart, Tomando el mensaje de Jesús de servicio amoroso a corazón, all are welcome in our vibrant, hopeful, diverse, todos son bienvenidos en nuestra Comunidad Eucarística vi- Eucharistic Community where we break the bread brante, llena de esperanza, y diversa, and open the Word and discover God in our Midst. donde partimos el Pan y abrimos la Palabra y descubrimos a Dios en medio de nosotros. Jesus needed followers, too. SFDSNYC.ORG THOSE IN OUR PRAYERS MASS INTENTIONS SICK & DEPARTED SATURDAY, DECEMBER 8, 2018 SICK 5pm - Edgar Almocente (D) Daniel Lynch, Katie Cummings, Jose Torres, Martin Vito-Cruz, Martin Peña, Laughlin Toolin, Sr. Joan Inglis, John Raimundi, Adri- SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9 , 2018 ana Benitez, Victoria Criloux, Julia Comet 9am - Rosemary McCann (D) 11am - Rose Stella (D) DECEASED 12:30am - Kevin Varella Luco (D) Thomas Perkins, Margaret Whalen, George McDonald, Catherine Ryan, Carlos Mauleon, Renzo Ventrello MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2018 8:30am - Doris Clemencia Zaros (D) HAVE A SPECIAL PRAYER REQUEST? TUESDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2018 Send us who or what needs a special prayer by using the 8:30a– Prayer Request feature on our new SFDS app—available in the WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2018 Google Play or Apple App Store.