This Week's Podcast Features the Bizarre Life and Military Career of Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Wintle MC of the Royals. YOU C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London View Management Framework SPG MP26

26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to 219 Horse Guards Road 424 The St James’s Park area was originally a marshy water meadow, before being drained to provide a deer park for Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. The current form of the park owes much to Charles II, who ordained a new layout, incorporating The Mall, in the 1660s. The park was remodelled by John Nash in 1827-8 and his layout survives largely intact. St James’s Park is maintained to an extremely high standard and the bridge across the lake provides a frequently visited place from which to appreciate views through the Park. The landscape is subtly lit after dark. St James’s Park is included on English Heritage’s Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest at Grade I. 425 There is one Viewing Location at St James’ Park 26A, which is situated on the east side of the bridge over the lake. 220 London View Management Framework Viewing Location 26A St James’s Park Bridge N.B for key to symbols refer to image 1 Panorama from Assessment Point 26A.1 St James’s Park Bridge – near the centre of the bridge 26 Townscape View: St James’s Park to Horse Guards Road 221 Description of the View 426 The Viewing Location is on the east side of the footbridge Landmarks include: across the lake. The bridge was built in 1956-7 to the designs Whitehall Court (II*) of Eric Bedford of the Ministry of Works. Views vary from Horse Guards (I) either end of the bridge and a near central location has been The Foreign Office (I) selected for the single Assessment Point (26A.1) orientated The London Eye towards Horse Guards Parade. -

The Royal Tour : the Wedding of Hrh Prince William of Wales to Catherine ‘Kate’ Middleton

THE ROYAL TOUR : THE WEDDING OF HRH PRINCE WILLIAM OF WALES TO CATHERINE ‘KATE’ MIDDLETON Trip Highlights: Buckingham Palace Westminster Abbey Windsor Castle Hedsor House Kensington Palace Edinburgh Castle TUESDAY ARRIVE LONDON 26 APRIL 2011 Arrive London Heathrow Airport and meet your guide who will escort you to your coach for transfer directly to central London for a panoramic sightseeing tour. Sights include Westminster Abbey, Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, St. Paul’s Cathedral and Buckingham Palace. Continue to your hotel in central London, where accommodation is reserved for 6 nights on a bed and breakfast basis. WEDNESDAY WINDOR CASTLE—THE TOWER OF LONDON 27 APRIL 2011 This morning visit Windsor Castle one of three official residences of The Queen, and the home to the Sovereign for over 900 years. The imposing towers and battlements of the Castle loom large from every approach to the town, creating one of the world's most spectacular skylines. No other royal residence has played such an important role in the nation's history. You will also visit St George's Chapel, one of the most beautiful ecclesiastical buildings in England. There will be time at leisure to enjoy lunch before travelling to the Tower of London, home to the Crown Jewels and an integral part of British Royal history. Here you will discover the Tower’s 900‐year history as a Royal Palace and fortress, prison and place of execution, mint, arsenal, menagerie and jewel house. THURSDAY LONDON : KEW PALACE—KENSINGTON PALACE 28 APRIL 2011 This morning visit Kew Palace, the smallest of English Royal Palaces with its privacy that made it the favourite country retreat for the Royal family in the late 18th century. -

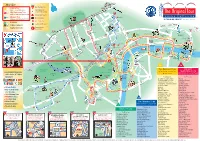

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

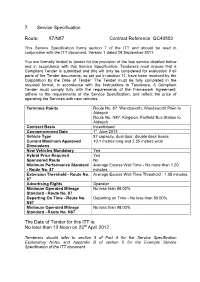

7. Service Specification Route

7. Service Specification Route: 87/N87 Contract Reference QC40803 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Route No. 87: Wandsworth, Wandsworth Plain to Aldwych Route No. N87: Kingston, Fairfield Bus Station to Aldwych Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 1st June 2013 Vehicle Type 87 capacity, dual door, double deck buses Current Maximum Approved 10.1 metres long and 2.55 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.20 - Route No. 87 minutes Extension Threshold - Route No. Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 1.05 minutes 87 Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. 87 Departing On Time - Route No. Departing on Time - No less than 85.00% N87 Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard - Route No. -

An Examination of the Artist's Depiction of the City and Its Gardens 1745-1756

Durham E-Theses Public and private space in Canaletto's London: An examination of the artist's depiction of the city and its gardens 1745-1756 Hudson, Ferne Olivia How to cite: Hudson, Ferne Olivia (2000) Public and private space in Canaletto's London: An examination of the artist's depiction of the city and its gardens 1745-1756, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4252/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Public and Private Space in Canaletto's London. An Examination of the Artist's Depiction of the City and its Gardens 1745-1756. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. -

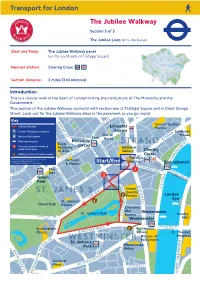

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

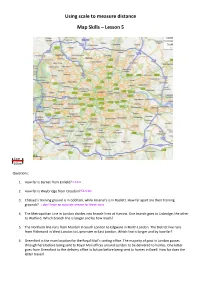

Using Scale to Measure Distance Map Skills – Lesson 5

Using scale to measure distance Map Skills – Lesson 5 1cm 10km Questions: 1. How far is Barnet from Enfield? 2. How far is Weybridge from Croydon? 3. Chelsea’s training ground is in Cobham, while Arsenal’s is in Radlett. How far apart are their training grounds? 4. The Metropolitan Line in London divides into branch lines at Harrow. One branch goes to Uxbridge, the other to Watford. Which branch line is longer and by how much? 5. The Northern line runs from Morden in South London to Edgware in North London. The District line runs from Richmond in West London to Upminster in East London. Which line is longer and by how far? 6. Greenford is the main location for the Royal Mail’s sorting office. The majority of post in London passes through here before being sent to Royal Mail offices around London to be delivered to homes. One letter goes from Greenford to the delivery office in Sutton before being sent to homes in Ewell. How far does the letter travel? The map below zooms in on the area of Westminster. 1cm 75m QUESTIONS: 1. The Houses of Parliament is shown by its proper name of the Palace of Westminster on this map. How far does the Prime Minister have to travel to get from 10 Downing Street to Parliament? 2. Horse Guards Parade will be the venue of the Beach Volleyball at this summer’s Olympic Games. How far is it from Charing Cross station? 3. How long is Westminster Bridge? 4. A walking tour of the government buildings starts at Big Ben, goes up Parliament St and Whitehall, along Northumberland Avenue, and back down the Victoria Embankment. -

Science in London - Trip ID #165187 May 29 - June 4, 2019 ITINERARY OVERVIEW

Educational Travel Experience Designed Especially for St Mary's High School Science in London - Trip ID #165187 May 29 - June 4, 2019 ITINERARY OVERVIEW DAY 1 DEPARTURE FROM RALEIGH DAY 2 ARRIVE LONDON (5 NIGHTS) DAY 3 LONDON (LONDON'S FAVORITE HAUNTS) DAY 4 LONDON (KINGS AND QUEENS OF ENGLAND) DAY 5 LONDON (ARTIFACTS & ARCHITECTURE IN LONDON) DAY 6 LONDON (INVESTIGATIONS) DAY 7 DEPARTURE FROM LONDON ITINERARY England is a fascinating country with a long and rich history that continues to intrigue visitors to this day. In its earliest days the country was a consistent target for invasion and occupied by the Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, and Normans, all of whom left distinctive marks on the national identity. Over the centuries, its people have made a significant impact throughout the world in trade, colonization, religion, literature, art, and industry. No amount of time here ever seems enough to fully experience all that the country has to offer. Educational Tour/Visit Cultural Experience Festival/Performance/Workshop Tour Services Recreational Activity LEAP Enrichment Match/Training Session DAY 1 Wednesday, 29 May 2019 Relax and enjoy our scheduled flight from Raleigh to London-Heathrow, England DAY 2 Thursday, 30 May 2019 Our 24-hour Tour Director will meet us at the airport and remain with us until our final airport departure. Our private coach will be waiting to transfer us to our hotel in London. For the next five evenings we will enjoy the convenience of our centrally-located London hotel, where daily breakfast will be included. London is the largest city in Europe: quite a feat, considering its location on a relatively small island. -

Queen Elizabeth's Platinum Jubilee & Royal Palaces

NEW Queen Elizabeth’s Platinum Jubilee & Royal Palaces August 8 to 17, 2022 From $5,340 per person You are cordially invited on a grand tour of England’s Royal Palaces to celebrate one of the most historic milestones in British history, Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee. During this regal affair we discover a fascinating range of sovereign landmarks; starting in London before venturing further afield to Cambridge, King’s Lynn and of course Windsor. Follow in the footsteps of Britain’s longest-reigning monarch as we Buckingham Palace weave our way around a splendid collection of magnificent palaces, Royal residences, famous country retreats and some of the Special extras included most glorious gardens in England. in your itinerary Ten Day Itinerary Guided tour of Royal London August 8: Arrival (depart U.S. on 8/7) Guided tour of Eltham Palace On arrival at Heathrow airport, a private transfer Audio guided tour of Buckingham Palace will take you to The Royal Horseguards Hotel, Guided tour of Clarence House where we stay for the first four nights of our tour. In the evening, join the group for a welcome drink, Guided out-of-hours private tour of followed by dinner. Kensington Palace Meals: Dinner Private guided tour of Hampton Court Palace August 9: Royal London, Guided walking tour of Cambridge Eltham Palace and Guided tour of Burghley House Queen’s House Greenwich Guided tour of Hatfield House We start today with a guided tour of Royal London, Audio guided tour of Windsor Castle by coach and on foot, which includes the Tower of Guided tour of Frogmore House London, the oldest building in London. -

London Buses - Route Description

Printed On: 05 June 2018 17:33:49 LONDON BUSES - ROUTE DESCRIPTION ROUTE 87: Wandsworth, Wandsworth Plain - Aldwych Date of Structural Change: 2 June 2018. Date of Service Change: 2 June 2018. Reason for Issue: New contract. STREETS TRAVERSED Towards Aldwych: Wandsworth Plain, Armoury Way, Fairfield Street, East Hill, St John's Hill, Lavender Hill, Wandsworth Road, Vauxhall Bus Station, Bridgefoot, Vauxhall Bridge, Millbank, Millbank Roundabout, Millbank, Abingdon Street, Old Palace Yard, St Margaret Street, Parliament Square, Parliament Street, Whitehall, Charing Cross, Trafalgar Square (South Side), Strand, Aldwych. Towards Wandsworth, Wandsworth Plain: Strand, Charing Cross, Whitehall, Parliament Street, Parliament Square, St Margaret Street, Old Palace Yard, Abingdon Street, Millbank, Millbank Roundabout, Millbank, Vauxhall Bridge, Bridgefoot, Vauxhall Bus Station, Parry Street, Wandsworth Road, Lavender Hill, St John's Hill, Marcilly Road, North Side Wandsworth Common, Huguenot Place, East Hill, Wandsworth High Street, Wandsworth Plain. AUTHORISED STANDS, CURTAILMENT POINTS, & BLIND DESCRIPTIONS Please note that only stands, curtailment points, & blind descriptions as detailed in this contractual document may be used. WANDSWORTH, WANDSWORTH PLAIN Public stand for two buses on west side of Wandsworth Plain, commencing 7 metres south of lamp standard 2 extending 25 metres south. Buses proceed from Wandsworth Plain direct to stand, departing to Wandsworth Plain. Set down in Wandsworth Plain, at Stop F (33434 - Wandsworth Plain, Last Stop on LOR: 33434 - Wandsworth Plain) and pick up in Wandsworth Plain, at Stop G (33274 - Wandsworth Plain, First Stop on LOR: 33274 - Wandsworth Plain). AVAILABILITY: At any time. OPERATING RESTRICTIONS: No more than 2 buses on Route 87 should be scheduled to stand at any one time. -

The Queen's Guard

The Queen's Guard By Dolores Eamets, Silver Põlgaste and Liina Reimann Who is The Queen´s Guard? ● The Queen's Guard is the name given to the contingent of infantry responsible for guarding Buckingham Palace and St James' Palace in London. ● The guard is made up of a company of soldiers from a single regiment, which is split in two, providing a detachment for Buckingham Palace and a detachment for St James' Palace. ● The Guards have served ten Kings and four Queens. History ● The Queen's Guard have served Sovereign and the Royal Palaces since 1660. ● Until 1689, the Sovereign lived mainly at the Palace of Whitehall and was guarded there by Household Cavalry. ● In 1689, the court moved to St James' Palace, which was guarded by the Foot Guards. ● When Queen Victoria moved into Buckingham Palace in 1837, the Queen's Guard remained at St James' Palace, with a detachment guarding Buckingham Palace, as it still does today. The Household Cavalry Regiments There are two Household Cavalry Regiments - The Life Guards and The Blues and Royals. The Guard changing ceremony at Buckingham Palace ● It takes place at 11.30 am. ● The handover is accompanied by a Guards band. ● It is also known as ‘Guard Mounting’. ● The New Guard, who during the course of the ceremony become The Queen’s Guard, march to Buckingham Palace from Wellington Barracks. ● During the Changing the Guard ceremony one regiment takes over from another. The Guard changing ceremony at St James' Palace • It takes place daily at 11.00 am (10.00 am on Sundays). -

View of the Sound

SCOTS GUARDS ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER That some no longer serve with the colours does not matter, What does matter is that we are all of us Scots Guardsmen. Bound together in the Queen’s service until we die by a chain, the links of which are invisible but which are as strong as steel: Constantly striving, in all that we do, to maintain the high traditions of loyalty and devotion to duty upon which the Scots Guards are founded. General Sir Michael Gow GCB Neil Crockett June 2019 Secretary & Editor Volume 20 Issue 5 Website Email www.scotsguards.co.uk [email protected] Enquires Tel: 01383 -721530 FRONT PAGE PHOTOGRAPHS 2nd Battalion Scots Guards Falklands Memorial – Ajax Bay By Major James Kelly, Regt Adjutant I have been in correspondence with Major General Rupert Jones (son of the late Colonel H) who is President of the Falkland Islands Memorial Trust. He told me a few months ago that the SG memorial had inadvertently been built just inside the white painted ring of white stones that delineated where the fallen had been temporarily buried before receiving proper graves, and therefore technically in consecrated ground. Having consulted with Ronnie Paterson to ensure that those who originally built the cairn were not going to be offended, the stones have been very sensitively moved and rebuilt a few feet further up the hill, commanding the same (if not better) view of the Sound. Therefore, it is now outside the consecrated grave area and thus no one now will need to tread into the consecrated area to look at and read the memorial and its inscription.