Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK University Sports Scholarships / Funding / Bursaries

Sports scholarship information for prospective university water polo students Institution Sports Scholarship opportunities 1. Aberyswtwyth University For details about Aberyswtwyth’s Sports Scholarships, click here: http://www.aber.ac.uk/en/undergrad/fees-finance/scholarships/uk-eu 2. Anglia Ruskin University Anglia Ruskin University has a sports scholarship that is offered to students who compete at regional, national or international level. The scholarship is worth up to £1,000 per year over a three year period and is tailored to the needs of the individual. Further details of the scheme can be obtained by emailing [email protected] 3. Bath University Offer high-performance scholarships. For more information, click here: http://www.teambath.com/athlete-zone/scholarships 4. Bedford University Offer high-performance scholarships. For more information, click here: http://www.beds.ac.uk/sportbeds/sportscholarships 5. Bolton University Offer high-performance scholarships. For more information, click here: http://www.bolton.ac.uk/Undergraduate/FeesFunding/Scholarships/Bolton- Sports-Bursary.aspx 6. Bristol University Sporting awards are available and successful applicants will have had considerable success at representative level. It would be unusual for an award to be given to a student who had not had International honours, at least at junior level. Although a student might apply for other scholarships, such as the government funded Talented Athlete Sports Scheme awards, the holder of a Vice-Chancellor’s award must not hold other funded sporting grants. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/fees-funding/awards/vc-scholarship 7. Cardiff University Offer a High Performance Programme bursary. For more information, click here: http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/sport/performance/bursary 8. -

Rules for Candidates Wishing to Apply for a Two Year

GENERAL 2022 1. Up to fifty Marshall Scholarships will be awarded in 2022. They are tenable at any British university and for study in any discipline at graduate level, leading to the RULES FOR CANDIDATES WISHING TO award of a British university degree. Conditions APPLY FOR A TWO YEAR MARSHALL governing One Year Scholarships are set out in a SCHOLARSHIP ONLY. separate set of Rules. Marshall Scholarships finance young Americans of high 2. Candidates are invited to indicate two preferred ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom in a universities, although the Marshall Commission reserves system of higher education recognised for its excellence. the right to decide on final placement. Expressions of interest in studying at universities other than Oxford, Founded by a 1953 Act of Parliament, Marshall Cambridge and London are particularly welcomed. Scholarships are mainly funded by the Foreign, Candidates are especially encouraged to consider the Commonwealth and Development Office and Marshall Partnership Universities. A course search commemorate the humane ideals of the Marshall Plan facility is available here: conceived by General George C Marshall. They express https://www.marshallscholarship.org/study-in-the- the continuing gratitude of the British people to their uk/course-search American counterparts. NB: The selection of Scholars is based on our The objectives of the Marshall Scholarships are: published criteria: https://www.marshallscholarship.org/apply/criteria- • To enable intellectually distinguished young and-who-is-eligible This includes, under the Americans, their country’s future leaders, to study in academic criteria, a range of factors, including a the UK. candidate’s choice of course, choice of university, and academic and personal aptitude. -

PROSPECTUS College of Science 01

01 PROSPECTUS College of Science 01 ON THE COVER The Nature of Light ‘Illuminating our understanding of future technologies’ by Joss Whittle, Department of Computer Science, College of Science, in collaboration with Mark Jones, supervisor. WHAT IS RESEARCH AS ART? Swansea University’s Research as Art competition encourages researchers to engage with different audiences in their research through a striking image and captivating text. The annual competition has attracted over 500 stunning entries since its inception in 2009, representing every academic college, and has been seen by 50 million people worldwide. Please note that this image is generated by algorithms and is not a photograph. 02 03 CONTENTS WELCOME TO THE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE COMPUTER SCIENCE COMPUTATIONAL COURSE COURSES FOUNDRY BAY CAMPUS INFORMATION It’s fantastic that you are considering Swansea University as a key next step in your future and career. As Head of Science I wanted 06 07 08 10 to tell you how important every member of our community is: if you join us, you’ll be able to play an important role in the world- changing work we do. STUDENT CAREERS AND ABOUT GO BEYOND PROFILES EMPLOYABILITY SWANSEA We are proud to welcome be encouraged to share your people into our ‘family’ from knowledge with others too. 14 18 22 26 many backgrounds and from around the world. Science In this brochure, you’ll find moves forward where there is specific information on your STAFF TECHNOCAMPS RESEARCH STUDENT LIFE INCLUSIVITY diversity and we encourage specialist subject. You’ll Professor Matt Jones, many perspectives, voices and see that you’ll be taught by Head of the hearts to become involved in world-leading researchers and College of Science 27 28 29 30 our activities as we become teachers who are committed one of the most creative, to your education. -

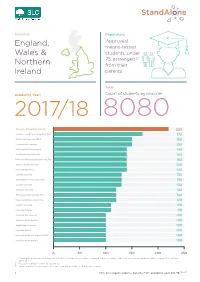

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Cardiff University International Prospectus 2021

Cardiff University International Prospectus 2021 www.cardiff.ac.uk/international www.cardiff.ac.uk/international bienvenue The photographs in this prospectus are of Cardiff University students, locations at Cardiff University and the city of Cardiff. studying at cardiff university www.cardiff.ac.uk/international welcome Cardiff University has been producing successful Contents graduates since 1883, combining a prestigious About Us heritage with modern and innovative facilities. 04 #WeAreInternational 06 Research The University has changed dramatically over the 08 Studying at Cardiff University last 137 years, but the 10 About Cardiff University commitment to quality 12 Career prospects education and a rewarding 14 Cardiff, the capital city of Wales university experience remains. 16 Accommodation 18 University life 20 The future Course List 21 Courses and Schools directory Enhancing Your Studies 42 Study Abroad 43 Global Opportunities 44 English Language Programme Next Steps 47 How to apply 49 Money and living expenses 50 University map 3 3 studying at cardiff university #WeAreInternational Cardiff University is truly international. With over 8,600 international students from more than 130 countries stepping through our doors each year, our student population is diverse and multicultural. We recruit worldwide for the best academic talent who help to deliver a rich and engaging study environment. The University reaches far beyond its home in Wales, with hundreds of overseas partnerships and research projects around the world, contributing to our ever-growing global community. University of Bremen Cardiff Carlos Jiminez Santillan, University * Mexico MSc Operational Research and Applied Statistics, 2018 Discovery Partners “Cardiff is such an amazing city to Institute (DPI) live in . -

Support for Foundation Years Annex

Support for foundation years Annex: List of respondents Contents Code Name Organisation Page WGFY001 Maggie Griffiths Grwp Llandrillo Menai 2 WGFY002 Simon Murray Cardiff West Communities First 4 WGFY003 Dean Jones Ace/Community First Ely 6 WGFY004 Stefan Kelly Cardiff Met Students Union 7 WGFY005 Anonymous Anonymous 10 WGFY006 Anonymous Anonymous 11 WGFY007 Philip Davies St. Cyres School, Penarth 12 WGFY008 Liz Hayes Cardiff Metropolitan University 14 WGFY009 Ian Pretty 157 Group 18 WGFY010 Anonymous Anonymous 20 WGFY011 Prof Colin Riordan Cardiff University 21 WGFY012 Anonymous Anonymous 27 WGFY013 Prof Martin Stringer Swansea University 28 WGFY014 Prof Maria Hinfelaar Wrexham Glyndwr 34 WGFY015 Michelle Matheron The Open University 44 WGFY016 Dr Willy Kitchen Foundation Year Network 47 WGFY017 Leanne Holborn HEFCW 54 WGFY018 Pierre Cox VOICE 59 WGFY019 Ian Toone VOICE 61 WGFY020 Anonymous Anonymous 64 WGFY021 Karen Williams UCU Wales 65 WGFY022 Gwyndaf Tobias Uni. Of Wales Trinity Saint David 68 WGFY023 Tim Pratt Associate of School and College 71 Leaders(Cymru) WGFY024 David.B.Jones Coleg Cambria 72 WGFY025 David Price Cardiff Metropolitan University 77 WGFY026 Ben Arnold Universities Wales 84 WGFY027 Judith Davison University of Huddersfield 99 WGFY028 Greg Walker Colegau Cymru 100 WGFY029 Mary Van Del Heuvel ATL Cymru 104 WGFY030 Beth Button NUS Wales 107 WGFY031 Anonymous Anonymous 111 1 WGFY001 Name - Maggie Griffiths Organisation - Grwp Llandrillo Menai Question 1 – We have outlined a series of concerns regarding foundation year provision, principally that it represents poor value for money and does not obviously provide any benefit to the student when compared to the available alternative routes to higher education. -

PG Prospectus 2019

swansea.ac.uk/postgraduate 2019 POSTGRADUATE Swansea University I believe that collaboration is the key to change. Dr Lella Nouri, Senior Lecturer – Criminology POSTGRADUATE 2019 SwanseaPostgrad SwanseaPostgrad Swansea Uni #SwanseaUni UK UK OPEN DAYS TOP 10 TEACHING TOP 30 BEST UNIVERSITY EXCELLENCE RESEARCH EXCELLENCE 7 November 2018 6 March 2019 (WhatUni Student Choice Awards 2018) (QS Stars global university ratings system 2017) (Research Excellence Framework 2014-2021) (Singleton Park Campus) (Singleton Park Campus) 14 November 2018 13 March 2019 UK (Bay Campus) (Bay Campus) 3RD TOP 10 MOST AFFORDABLE GREENEST UNIVERSITY UK UNIVERSITY TOWN Swansea University £89 average weekly rent (Guardian People & Planet University League 2017) (totallymoney.com 2018) LOOK WHO’S MAKING WAVES AT SWANSEA UNIVERSITY... DR LELLA NOURI ALEX RUDDY ELINOR MELOY A pioneer in cyberterrorism research Trainee doctor with fighting spirit Ecologist who wants to Page 20 Page 30 change the world Page 40 SwanseaPostgrad swanseauni Swansea Uni swanseauni swanseauni WELCOME FROM OUR VICE-CHANCELLOR Swansea University has been at the This is an exciting time to join us. We have cutting edge of research and innovation invested over £750 million in our facilities since 1920. to provide you with the best environment in which to conduct your research. As a We have a long history of working with postgraduate student, you will be a valued business and industry but today our world member of our academic community with class research has a much wider impact access to the expertise of research staff, across the health, wealth, culture, and many of whom are world renowned leaders well-being of our society. -

Graduate Start-Ups in Wales

GRADUATE START-UPS IN WALES Universities Wales Prifysgolion Cymru WHERE IN WALES BANGOR WREXHAM ABERYSTWYTH LAMPETER CAMARTHEN PONTYPRIDD NEWPORT CARDIFF SWANSEA 2 CONTENTS 4/5 Introduction 6/7 Aberystwyth University 8/9 Bangor University 10/11 Cardiff Metropolitan University 12/13 Cardiff University 14/15 The Open University in Wales 16/17 Swansea University 18/19 University of South Wales 20/21 University of Wales Trinity Saint David 22/23 Wrexham Glyndwr University 24 Contact Details 3 INTRODUCTION Across Wales, universities play a Entrepreneurship by students and be an important part of Wales’ future crucial role in supporting and driving graduates has been an important economic prosperity. the Welsh economy. An independent focus for Universities Wales over study found that Welsh universities the past 12 months. We have The support that universities offer in 2015/16 generated £5bn of output worked to highlight the innovative these Start-ups is broad including and nearly 50,000 jobs in Wales. The and valuable contribution these practical assistance on office space, nature of that economic contribution businesses make to Wales and the bursaries to help with setup costs, is broad, from directly employing staff ways in which universities support and support in identifying and to research and innovation links with those students and graduates on securing investment opportunities. communities and employers. their Start-up journey. Students and graduates also benefit from mentoring and advice from tutors, Perhaps an area that isn’t always Wales performs well on graduate lecturers and dedicated enterprise considered when examining the Start-ups. The annual Higher staff who offer support on every step impact of our universities is the ways Education Business and Community of the Start-up journey. -

Fee & Access Plan 2020-21

Annex A 2020-21 Fee and Access Plan Application Template Institution name: Swansea University Institution The Abbey address: Singleton Park Swansea University SA2 8PP Main contact Alternate contact Contact name: Mr Robert Bowen Professor Martin Stringer Job title: Head of Planning & Pro-Vice-Chancellor Performance Telephone 01792 606235 01792 602149 number: Email address: [email protected] [email protected] Swansea University 2020-21 Fee and Access Plan 1 Swansea University Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................... 3 2. DURATION OF FEE AND ACCESS PLANS ............................................. 5 3. FEE LEVELS ........................................................................................ 5 4. STUDENT PARTNERSHIP .................................................................... 7 5. STRATEGIC REVIEW ........................................................................... 8 6. GROUPS UNDER-REPRESENTED IN HIGHER EDUCATION .................. 19 7. OBJECTIVES, ACTIVITIES AND TARGETS ............................................ 22 EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY ........................................................................ 22 EOP 1 - ATTRACT ................................................................................ 22 EOP 2 - EFFECTIVE INFORMATION ........................................................... 25 EOP 3 - RETENTION ............................................................................. 29 EOP 4 - PROGRESSION ........................................................................ -

The 100+ Ways Universities Have Improved Everyday Life

THE 100+ WAYS UNIVERSITIES HAVE IMPROVED EVERYDAY LIFE Explore The UK’s Best Breakthroughs List is a celebration waste without the need for water; the development of the everyday impact that universities have on of a new scrum technique to make rugby safer; a people, lives and communities across the UK. sports initiative that aims to use football to resolve conflict in divided communities; – and even work UK universities are at the forefront of some of the to protect the quality of the chocolate we eat. world’s most important discoveries, innovations and social initiatives, including the creation of the It was put together in partnership with universities internet, work tackling plastic pollution, ultrasound across the UK. As part of the MadeAtUni campaign, scans to check the health of unborn babies and the every university in the country was invited to establishment of the Living Wage. nominate the one thing from their institution which they believe has had the biggest impact on people, The list also highlights the less celebrated lives or communities. breakthroughs that transform lives, regardless of whether you’ve been to university or not. These Over 100 universities submitted a nomination and include a specially-designed bra to help women the entries cover health, technology, environment, undergoing radiotherapy; a toilet that flushes human family, community, and culture & sport. Explore DISCOVER WALES’ UNIVERSITY NOMINATIONS OR EXPLORE ALL THE BREAKTHROUGHS BY THEME THEMES > University of Aberystwyth > Bangor University > Cardiff University > Cardiff Metropolitan University > University of Swansea > University of South Wales > Wrexham Glyndŵr University ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY New varieties of grass to help the environment There’s science behind the green, green Today almost a third of the perennial grass of home. -

Programme and Abstracts

- Programme and Abstracts - The 1 st Welsh Postgraduate Research Conference in Business/Management & Economics is hosted by Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, UK Organizing Committee: Luigi De Luca, Nicole Koenig-Lewis, Kate Daunt and Beverly Francis 1 | WPRGC2019 1st Welsh Postgraduate Research Conference in Business/Management & Economics Cardiff Business School, 19 th June 2019 Programme Cardiff Business School, Postgraduate Teaching Centre 09:30 Registration + Coffee/Tea: PTC Building Foyer 10:00 Opening Session: Room 1.19 Welcome address – Prof. Rachel Ashworth, Dean and Head of Cardiff Business School 10:30-12:00 Parallel Sessions 1 10:30-12:00 Parallel session 1A: Room 0.22 Session Chairs/Discussant: Patrick Minford & Onur Tosun 1. Capital structure and political connections: Evidence from GCC countries Fatma Ahmed, Swansea University 2. Politics and the behaviour of the Regional Development Banks Ridhotama Shanti Darsih Ottemusu, Bangor University 3. Testing a monetary model of the UK using the method of indirect inference Juyi Lyu, Cardiff Business School 4. The effects of quantitative easing in UK: A study through financial accelerator with SOE-DSGE Model Ziqing Wang, Cardiff Business School 2 | WPRGC2019 10:30-12:00 Parallel session 1B: Room 0.23 Session Chairs/Discussant: Louise Hassan & Anita Zhao 1. Understanding Trust Building Process in Indonesian Islamic Banking Context Savira Ansory, Cardiff Business School 2. Exploring the action-inaction asymmetry in the theory of planned behaviour framework Georgina Smith, Bangor University 3. Exploring factors affecting mobile payment adoption in Indian context Pushp Patil, Swansea University 4. Consumer-object relationship: a study of psychological ownership in access-based fashion consumption Bader Alkaffary, Cardiff Business School 10:30-12:00 Parallel session 1C: Room 0.24 Session Chairs/Discussant: Calvin Jones & David Blackaby 1. -

University Patenting in Wales and Scotland

University Patenting in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: A Comparative Analysis Andrew Beale, David Blackaby and Lynn Mainwaring, Swansea University, Abstract Using data on the patent portfolios of UK HEIs, the paper compares the levels of patenting activity (filings and grants) and patent quality (patents with commercial co- assignees and patent citations) at Welsh, Scottish and N. Irish institutions. Patent activity, per researcher, in Wales is on a par with that in Scotland and about twice the rate in Northern Ireland, but the academic research bases in Wales and N. Ireland are around half of that in Scotland in per capita terms. In respect of patent quality, Wales clearly lags Scotland and there are signs that it is falling behind N. Ireland. We conclude that bolder steps are needed on the part of the Welsh Assembly Government to develop the HEI-business interface. 1 Introduction The traditional research ‘mission’ of universities has been the generation of research outputs as public goods. Academics are strongly motivated by, and institutionally rewarded for, disseminating their findings in open-access academic journals of the highest standing and, therefore, of the highest readership among their peer groups. This approach is exemplified and reinforced in the UK by institutionalised procedures such as the regular Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) conducted by the Higher Education Funding Councils as a means of determining the allocation of public research monies. Publication is the main determinant of RAE success, and although