Brenda FLORIO Et Al. Plaintiffs, V. RYOBI TECHS., INC. Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

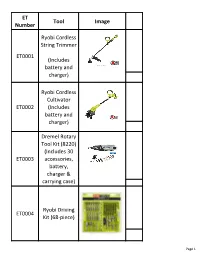

ET0001 Ryobi Cordless String Trimmer

ET Tool Image Number Ryobi Cordless String Trimmer ET0001 (Includes battery and charger) Ryobi Cordless Cultivator ET0002 (Includes battery and charger) Dremel Rotary Tool Kit (8220) (Includes 30 ET0003 accessories, battery, charger & carrying case) Ryobi Driving ET0004 Kit (68-piece) Page 1 ET Tool Image Number Ryobi Wood ET0005 Drilling Kit (11- piece) Ryobi Impact ET0006 Driving Kit (26- piece) Ryobi Black ET0007 Oxide Drill Kit (21-piece_ Electrician's Tool Set (22- ET0008 piece, includes bag) Page 2 ET Tool Image Number Steel Single ET0009 Painter's Pole (5 ft) Wood Extension Pole ET0010 with Metal Tip (4 ft) Light Bulb Changer Kit ET0011 with Attachments (11 ft) ET0012 Torch Kit Page 3 ET Tool Image Number ITEM NO ITEM NO LONGER ET0013 LONGER AVAILABLE AVAILABLE P3 Kill A Watt EZ ET0014 Electricity Usage Monitor P3 Kill A Watt EZ ET0015 Electricity Usage Monitor P3 Kill A Watt EZ ET0016 Electricity Usage Monitor Page 4 ET Tool Image Number Ryobi One+ 18V 4 1/2 in. Angle Grinder ET0017 (Includes bag, battery and charger) Ryobi One+ 18V Compact Drill/Driver Kit ET0018 (Includes bag, battery and charger) ITEM NO ITEM NO LONGER ET0019 LONGER AVAILABLE AVAILABLE Ryobi One+ 18V Orbital Jigsaw (Includes bag, ET0020 battery, charger and 1 blade) Page 5 ET Tool Image Number Ryobi One+ 18V Belt Sander (Includes bag, ET0021 battery, charger and dust bag) Ryobi One+ 18V Drain Auger ET0022 (Includes bag, battery and charger) Ryobi One+ 18V Base with Multi- tool ET0023 Attachments (Includes bag, battery and charger) Ryobi One+ 18V Impact Driver ET0024 (Includes bag, battery and charger) Page 6 ET Tool Image Number ITEM NO ITEM NO LONGER ET0025 LONGER AVAILABLE AVAILABLE Ryobi One+ 18V 6-1/2 in. -

Professional Power Tool Accessories OCKINGBIRD

Proposed 4th Edition Research for The North American Market Winter 2021 ©2020 Ciprus LLC All Rights Reserved ©2020 Ciprus LLC Professional Power Professional Accessories Tool Ciprus LLC • 9027 MOCKINGBIRD DRIVE • SUITE 201 • P.O. BOX 321 • SANIBEL, FL 339570321 • 860.767.7685 WWW.CIPRUS.COM The 2021 North American for Professional Power Tool Accessories Introduction Covid-19 has affected virtually all facets of our lives from how we live, & Research work and purchase our everyday needs. Many of these changes are im- pacting contractors as well. While traditional channels remain the Background mainstay of power tool accessory purchases, digital channels continue to grow in importance. Digital channels are time saving and convenient, but in the age of Covid-19 they may also be safer. Distributor consoli- dations are also playing a role in how professional contractors obtain their power tool accessories. Contractor distributor chains have contin- ued to grow often through acquisition. Contractor purchase data will be valuable in understanding the impact of these changes. Ciprus LLC is pleased to announce the 4th Edition of the North Ameri- can Market for Power Tool Accessories. Past Editions were published in 2004, 2011 and 2016 along with proprietary research in 1994 and 1998 The 2021 report, the most comprehensive of its type, will present a com- prehensive analysis of professional power tool accessory purchase ac- tivity in both the commercial and residential markets by 7 contractor types. The research will target 15 Professional Power Tool Accessories including all of the accessories shown in the chart below. I47.F?581?.I+J47.G++9.=,,422+7P. -

Exceptional People

EXCEPTIONAL PEOPLE Working At TTI About TTI TTI is a world-class leader in the design, manufacturing and marketing of Power & Hand Tools, Outdoor Power Equipment, and Floor Care Appliances for consumers, professional and industrial users in the repair and construction industries, home improvement, and home and commercial cleaning. Our powerful brand lineup includes: l Power & Hand Tools — Milwaukee, Empire, Stiletto, Ryobi, Hart, AEG l Outdoor Products — Homelite, Ryobi l Floor Care — Hoover, Dirt Devil, Oreck, Vax At TTI we focus on four key principals: l Powerful Brands l Innovative Products l Operational Excellence l Exceptional People We pride ourselves on attracting and retaining Exceptional People. It is the 24,000 employees of TTI that have propelled us to be a world class leader in power tool, hand tool, outdoor and floor care products. www.TTIGroup.com TTI has been listed on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong since 1990 (HKEx: 669) and maintains a Level 1 American Depositary Receipt (ADR) program through the Bank of New York (ADR: TTNDY). TTI Employees Fuel Innovation & Success In 1991 TTI had revenues of $300 million. 2017 reported $6.1 revenues were $6.1 billion. billion $300 million 1991 –––––––––––––––––––––2017 Working At TTI TTI offers tremendous career growth opportunity to our employees at all levels of the organization. Driven by the growth of our business, throughout TTI employees are given the opportunity to learn, develop and grow. Employees earn outstanding benefits and compensation packages. TTI is a fast paced, results driven environment where the sky is the limit. Compensation & Benefits At TTI TTI is proud to offer an outstanding package that includes: SALARY—Each employee receives competitive annual cash compensation. -

Original Filed in Clerk's Office

Case 1:09-cv-03308-RWS Document 1 Filed 11/24/09 Page 1 of 12 ORIGINAL FILED IN CLERK'S OFFICE NOV 2 4 2009 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA s . , ATLANTA DIVISION HITACHI KOKI CO ., LTD ., Plaintiff, V. Civ' Action No. : TEexTRONZC INDUSTRIES CO. LTD., .~ . ~ n , TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES NORTH O9c!- AMERICA,- INC ., ONE WORLD TECHNOLOGIES, INC ., OWT INDUSTRIES INC ., MILWAUKEE ELECTRIC TOOL CORPORATION, and RYOBI TECHNOLOGIES, INC., Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff, Hitachi Koki Co ., Ltd., by its undersigned attorneys, complains of Defendants, Techtronic Industries Co . Ltd., Techtronic North America, Inc ., One World Technologies, Inc ., OWT Industries Inc., Milwaukee Electric Tool Corporation, and Ryobi Technologies, Inc ., and shows the Court as follows : NATURE OF LAWSUIT 1 . This is a claim for patent infringement arising under the patent laws of the United States, Title 35 of the United States Code . Case 1:09-cv-03308-RWS Document 1 Filed 11/24/09 Page 2 of 12 PARTIES AND PATENTS 2 . Hitachi Koki Co., Ltd. ("Hitachi Koki") is a foreign corporation organized and existing under the laws of Japan having a principal place of business at Shinagawa Intercity Tower A, 20`t' Floor, 15-1, Konan 2-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-6020, Japan . 3 . Hitachi Koki owns all right, title and interest in the following United States Patents : U. S . Pat. No. 7,207,251 entitled "Cutter With Laser Generator That Irradiates Cutting Position On Workpiece To Facilitate Alignment Of Blade With Cutting Position" ("the `251 patent"), and U. S . Pat. -

Stanley Black and Decker Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) Chevron

Who Owns What? Andrew Davis May, 2019 This is a redacted version of an article II found on protoolreviews.com. I remember growing up when General Motors offered different brands at different price points (until they all the brands started to overlap before GM collapsed) – Cadillac at the top end, followed by Oldsmobile, Buick, Pontiac, and Chevy. We have a similar situation in woodworking tools (also in kitchen appliances) except that in the case of tools, the multi-brand company is more often a case of acquisitions rather than organic development. Anyway, for those readers interested in the business side of tools, this column, which is a departure from my usual thread, may be of interest. Stanley Black and Decker Stanley Black & Decker (SBD) turned heads when it bought Craftsman Tools in 2017 after Sears closed 235 stores in 2015. Dating back to 1843 with a man named Frederick Stanley, the company merged in 2010 with Black and Decker. As of 2017, the company maintains a $7.5 billion business in tools & storage alone. SBD brands include: DeWalt Stanley Black + Decker Bostitch Craftsman Vidmar Mac Tools Irwin Lenox Proto Porter-Cable Powers Fasteners Lista Sidchrome Emglo USAG Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) TTI owns Milwaukee Tool and a host of other power tool companies. It also licenses the RIDGID and RYOBI names for cordless power tools (Emerson actually owns RIDGID and makes the red tools). Founded in 1985 in Hong Kong, TTI sells tools all over the world and employs over 22,000 people. TTI had worldwide annual sales of over US$6 billion in 2017. -

Tti Delivers a Decade of Record Results

[For Immediate Release] TTI DELIVERS A DECADE OF RECORD RESULTS Sustained Success by Accelerating the Transition to Cordless Tools Highlights 2019* 2018 US$’ US$’ million million Changes Sales 7,667 7,021 +9.2% Gross profit margin 37.7% 37.2% +50 bps EBIT 673 607 +10.9% Profit attributable to Owners of the Company 615 552 +11.3% Basic earnings per share (US cents) 33.67 30.16 +11.6% Dividend per share (approx. US cents) 13.26 11.33 +17.0% *For the year ended December 31, 2019 • Net profit grew 11.3% and sales expanded 9.2% • Gross margin improvement for the eleventh consecutive year • Flagship Milwaukee Tool business continues to grow 20%+ in local currency • RYOBI cordless sales delivered double-digit sales growth (Hong Kong, March 5, 2020) - Hong Kong-based global power equipment and floor care company Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. (“TTI” or the “Group”) (stock code: 669, ADR symbol: TTNDY) announced its results for the financial year ended December 31, 2019. The Group’s total revenue increased by 9.2% over the previous period to US$7.7 billion. The gross margin expanded from 37.2% in 2018 to 37.7% in 2019 driven by a flow of innovative new products, mix management, productivity gains and volume leverage. EBIT increased 10.9% to US$673 million, with the EBIT margin improving by 10 basis points to 8.8%. Shareholder’s profits rose 11.3% to US$615 million, with earnings per share increasing 11.6% over 2018 to US33.67 cents. Through disciplined working capital management, TTI delivered a gearing of 0.5% and working capital as 14.3% of sales. -

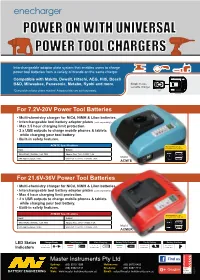

A4 Enecharger ACMTE & ACMGR Flyer 2-Pge V2 Low Colour

POWER ON WITH UNIVERSAL POWER TOOL CHARGERS Interchangeable adaptor plate system that enables users to charge power tool batteries from a variety of brands on the same charger. Compatible with Makita, Dewalt, Hitachi, AEG, Hilti, Bosch B&D, Milwaukee, Panasonic, Metabo, Ryobi and more. Simple to use, versatile charger Interchangeable Adaptor *Compatible adaptor plates required. Adaptor plates are sold separately. Plate Charger Base For 7.2V-20V Power Tool Batteries • Multi-chemistry charger for NiCd, NiMH & LiIon batteries. • Interchangeable tool battery adaptor plates (sold separately). • Max 2.5 hour charging limit protection. • 2 x USB outputs to charge mobile phones & tablets while charging your tool battery. • Built-in safety features. ACMTE Specifications Dual USB Ports: Suitable for smartphones & tablets. Input Output 100-240VAC, 50-60Hz, 1.2A, 70W Adaptor Port: 7.2V - 18VDC 1-3A Model: SAA approved power cable USB Port: 2 x 5VDC 2.1A max. each ACMTE For 21.6V-36V Power Tool Batteries • Multi-chemistry charger for NiCd, NiMH & LiIon batteries. • Interchangeable tool battery adaptor plates (sold separately). • Max 4 hour charging limit protection. • 2 x USB outputs to charge mobile phones & tablets while charging your tool battery. • Built-in safety features. ACMGR Specifications Dual USB Ports: Suitable for smartphones & tablets. Input Output 100-240VAC, 50-60Hz, 1.2A, 70W Adaptor Port: 21.6V - 36VDC 1-2A Model: SAA approved power cable USB Port: 2 x 5VDC 2.0A max. each ACMGR LED Status Indicators https://www.facebook.com/mi.battery.experts -

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Batteriesplus Recalls

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Office of Communications Washington, D.C. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Firm's Recall Hotline: (877) 856-3232 December 21, 2011 CPSC Recall Hotline: (800) 638-2772 Release #12-063 CPSC Media Contact: (301) 504-7908 BatteriesPlus Recalls Replacement Battery Packs Used with Cordless Tools Due to Explosion Hazard WASHINGTON, D.C. - The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, in cooperation with the firm named below, today announced a voluntary recall of the following consumer product. Consumers should stop using recalled products immediately unless otherwise instructed. It is illegal to resell or attempt to resell a recalled consumer product. Name of Product: Rayovac NI-CD Cordless Tool Battery Packs Units: About 111,800 Importer: BatteriesPlus LLC, of Hartland, Wis. Hazard: The replacement battery pack can explode unexpectedly, posing a risk of serious injury to consumers. Incidents/Injuries: BatteriesPlus has received five reports of exploding batteries. No injuries have been reported. Description: This recall involves RAYOVAC-branded replacement battery packs used with cordless power tools. “RAYOVAC,” “NI-CD” and a part number beginning with “CTL” are printed in white lettering on the product. The battery packs were sold in voltages ranging between 2.4 and 18 volts in various sizes and shapes. They were sold as replacement batteries to the following brand tools: Black and Decker, Bosch, DeWalt, Makita, Milwaukee, Panasonic, Ryobi and Skil. Sold exclusively at: BatteriesPlus retail stores nationwide and online at www.batteriesplus.com between June 2008 and October 2011 for about $60. Manufactured in: China Remedy: Consumers should immediately stop using and remove the battery packs from cordless tools. -

1 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of DELAWARE VICTORY INNOVATIONS COMPANY, INC., Plaintiff, V. TECHTRONIC I

Case 1:21-cv-00692-UNA Document 1 Filed 05/13/21 Page 1 of 12 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE VICTORY INNOVATIONS COMPANY, INC., Civil Action No. Plaintiff, v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES NORTH AMERICA, INC. and ONE WORLD TECHNOLOGIES, INC. d/b/a TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES POWER EQUIPMENT, Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff, Victory Innovations Company, Inc. (“Victory Innovations”), by and through its counsel, complains of Defendants, Techtronic Industries North America, Inc. (“TTI North America”) and One World Technologies, Inc. d/b/a Techtronic Industries Power Equipment (“One World”) (TTI North America and One World are hereinafter collectively referred to as “TTI”), as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is an action arising under the patent laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. § 1 et seq. THE PARTIES 2. Victory Innovations is a corporation organized under the laws of the State of Delaware with a place of business at 2300 Edison Boulevard, Twinsburg, Ohio 44087. Victory Innovations is in the business of, among other things, the design, marketing, sale, and support of cutting-edge battery-powered electrostatic sprayers. Victory Innovations advertises its 1 Case 1:21-cv-00692-UNA Document 1 Filed 05/13/21 Page 2 of 12 PageID #: 2 electrostatic sprayers on, for example, its website at https://www.victoryinnovations.com/. Victory Innovations offers both backpack and handheld versions of its electrostatic sprayers. (See, e.g., https://www.victoryinnovations.com/product/professional-cordless-electrostatic-backpack- sprayer/; https://www.victoryinnovations.com/product/professional-cordless-electrostatic-hand held-sprayer/.) 3. -

On Rehearing Published United States Court Of

ON REHEARING PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 14-1746 SD3, LLC; SAWSTOP LLC, Plaintiffs – Appellants, v. BLACK & DECKER (U.S.) INC.; BLACK & DECKER CORPORATION; CHANG TYPE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD.; DELTA POWER EQUIPMENT CORP.; HITACHI KOKI CO., LTD.; HITACHI KOKI USA LTD.; MAKITA CORPORATION; MAKITA U.S.A., INC.; MILWAUKEE ELECTRIC TOOL CORP.; ONE WORLD TECHNOLOGIES, INC.; OWT INDUSTRIES, INC.; ROBERT BOSCH GMBH; ROBERT BOSCH TOOL CORPORATION; RYOBI TECHNOLOGIES, INC.; STANLEY BLACK & DECKER, INC.; TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES, CO., LTD.; TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES NORTH AMERICA, INC.; PENTAIR WATER GROUP, INC.; EMERSON ELECTRIC COMPANY; PENTAIR, INC., Defendants – Appellees, and DEWALT INDUSTRIAL TOOLS; EMERSON ELECTRIC COMPANY, INC.; PENTAIR CORPORATION; PORTER-CABLE CORPORATION; SKIL POWER TOOLS, Defendants. ---------------------------- AMERICAN ANTITRUST INSTITUTE; NATIONAL CONSUMERS LEAGUE, Amici Supporting Appellants. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, at Alexandria. Claude M. Hilton, Senior District Judge. (1:14−cv−00191−CMH−IDD) Argued: May 12, 2015 Decided: October 29, 2015 Before WILKINSON, AGEE, and WYNN, Circuit Judges. Affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded by published opinion. Judge Agee wrote the opinion, in which Judge Wynn joined. Judge Wynn wrote a separate concurring opinion. Judge Wilkinson wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. ARGUED: Joel Davidow, CUNEO GILBERT & LADUCA, LLP, Washington, D.C., for Appellants. James Scott Ballenger, LATHAM & WATKINS, LLP, Washington, D.C., for Appellees. ON BRIEF: Jonathan W. Cuneo, Matthew E. Miller, CUNEO GILBERT & LADUCA, LLP, Washington, D.C., for Appellants. John D. Harkrider, Richard B. Dagen, AXINN, VELTROP & HARKRIDER LLP, Washington, D.C., Bernard J. -

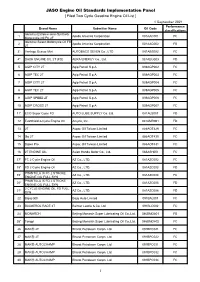

JASO Engine Oil Standards Implementation Panel

JASO Engine Oil Standards Implementation Panel [ Filed Two Cycle Gasoline Engine Oil List ] 1 September 2021 Performance Brand Name Submitter Name Oil Code classifications Idemitsu Extreme semi-Synthetic 1 Apollo America Corporation 001AAC001 FC Motorcycle Oil FC 2T Idemitsu Select Motorcycle Oil FB 2 Apollo America Corporation 001AAC002 FB 2T 3* Vantage Beaver Mini AUTOBACS SEVEN Co., LTD 081ABS002 FC 4* DASH ENGINE OIL 2T (FD) AERA ENERGY Co., Ltd. 081AEG003 FD 5 AGIP CITY 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP002 FC 6 AGIP TEC 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP003 FC 7 AGIP CITY 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP004 FC 8 AGIP TEC 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP005 FC 9 AGIP SPEED 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP006 FC 10 AGIP CROSS 2T Agip Petroil S.p.A. 039AGP007 FC 11* ECO Super Cycle FD AUTO LUBE SUPPLY Co. Ltd. 081ALS001 FD 12 EvoShield 2-Cycle Engine Oil Amyris, Inc. 001AMR001 FD 13 2T Aspac Oil Taiwan Limited 886AOT429 FC 14 Go 2T Aspac Oil Taiwan Limited 886AOT430 FC 15 Super Pro Aspac Oil Taiwan Limited 886AOT431 FC 16 2T ENGINE OIL Asian Honda Motor Co., Ltd. 066ASH001 FC 17* FC 2 Cycle Engine Oil AZ Co., LTD. 081AZC002 FC 18* FD 2 Cycle Engine Oil AZ Co., LTD. 081AZC003 FD PHANTULA IX FC 2 STROKE 19* AZ Co., LTD. 081AZC004 FC ENGINE OIL FULL SYN PHANTULA IX FD 2 STROKE 20* AZ Co., LTD. 081AZC005 FD ENGINE OIL FULL SYN 2 CYCLE ENGINE OIL FD FULL 21* AZ Co., LTD. 081AZC006 FD SYN 22 Bajaj GDI Bajaj Auto Limited 091BAL001 FC 23 BALMEROL RACE 2T Balmer Lawrie & Co. -

INNOVATION EXECUTION Annual Report 2005

Techtronic Industries Corporate Profile Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. (“TTI” or “the Group”) is a market and innovation leader in power equipment products, floor care appliances, laser and electronic products. We have a powerful portfolio of trusted brands, recognized for setting new standards in innovative design, technical advancements, marketing concepts and speed-to-market. Our portfolio of global brands include Milwaukee®, AEG®, Ryobi® and Homelite® for power equipment products, Royal®, Dirt Devil®, Regina® and Vax® for floor care appliances. TTI products are marketed through home centers, major retailers, full-line tool distributors and other channels in North America, Europe and other select markets. TTI is also the preferred partner of leading OEM brands and private label retail brands in North America and Europe. Headquartered in Hong Kong, the Group recorded sales of HK$22.36 billion in 2005, a collective achievement of its 22,000 staff worldwide. INNOVATION EXECUTION Annual Report 2005 Stock Code: 669 Corporate Profile Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. (“TTI” or “the Group”) is a market and innovation leader in power equipment products, floor care appliances, laser and electronic products. We have a powerful portfolio of trusted brands, recognized for setting new standards in innovative design, technical advancements, marketing concepts and speed-to-market. Our portfolio of global brands include Milwaukee®, AEG®, Ryobi® and Homelite® for power equipment products, Royal®, Dirt Devil®, Regina® and Vax® for floor care appliances. TTI products are marketed through home centers, major retailers, full-line tool distributors and other channels in North America, Europe and other select markets. TTI is also the preferred partner of leading OEM brands and private label retail brands in North America and Europe.