Davliatov Reply in Support of Motion For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guantanamo Detainees

The Equal Rights Trust (ERT) is an independent international organisation whose purpose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. Established as an advocacy organisation, resource centre and think tank, ERT focuses on the complex and complementary relationship between different types of discrimination, developing strategies for translating the principles of equality into practice. ©January 2010 The Equal Rights Trust ISBN: 978-0-9560717-2-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. The Equal Rights Trust Charles House, Suites N3-N6, 4th Floor 375 Kensington High Street London W14 8QH United Kingdom Tel. +44 (0)20 7471 5562 Fax: +44 (0)20 7471 5563 www.equalrightstrust.org The Equal Rights Trust is a company limited by guarantee incorporated in England and a registered charity. Company number 5559173. Charity number 1113288. Acknowledgements: This report was researched and drafted by David Baluarte, Practitioner-in-Residence, International Human Rights Law Clinic, American University Washington College of Law, acting as a Consultant to ERT. Stefanie Grant provided general advice. Amal De Chickera project-managed the work and finalised the report. Dimitrina Petrova edited and authorised the publication of the report. The Equal Rights Trust – From Mariel Cubans to Guantanamo Detainees Table of Contents Introduction: an Overview of Statelessness in the United States Paragraph 01 PART ONE Immigration Detention and Statelessness Paragraph 11 Statutory Framework for Post‐Removal Order Detention Paragraph 15 Interpreting the Statute: Zadvydas v. -

United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, Plaintiffs, DECLARATION OF JONATHAN HAFETZ v. 09 Civ. 8071 (BSJ) (FM) DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE; CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY; DEPARTMENT OF ECF Case STATE; DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Defendants. DECLARATION OF JONATHAN HAFETZ I, Jonathan Hafetz, under penalty of perjury declare as follows: 1. I represent plaintiffs the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation in this action concerning a FOIA request that seeks from the Department of Defense (“DOD”) and other agencies records about, among other things, prisoners at Bagram Air Base (“Bagram”) in Afghanistan. 2. I submit this declaration in support of plaintiffs’ motion for partial summary judgment and in opposition to the DOD’s motion for partial summary judgment. The purpose of this declaration is to bring the Court’s attention to official government disclosures, as well as information in the public domain, concerning the citizenship, length of detention, and date, place, and circumstances of capture of detainees held at the Bagram and similarly-situated suspected terrorists and combatants in U.S. military custody at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (“Guantánamo”). 1 Publicly-Available Information about Detainees at Bagram Prison 3. On April 23, 2009, plaintiffs submitted a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request to DOD, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Justice and the State Department seeking ten categories of records about Bagram, including records pertaining to detainees’ names, citizenships, length of detention, where they were captured, and the general circumstances of their capture. -

OSCE Yearbook 2011

Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy Hamburg (ed.) osC e 17 Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg / IFSH (ed.) OSCE Yearbook 2011 Yearbook on the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) • OSCE Yearbook osCe 2011 Nomos BUC_OSCE_2011_7311-7.indd 1 12.12.11 09:03 Articles of the OSCE Yearbook are indexed in World Affairs Online (WAO), accessible via the IREON portal. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de . ISBN 978-3-8329-7311-7 1. Auflage 2012 © Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2012. Printed in Germany. Alle Rechte, auch die des Nachdrucks von Auszügen, der photomechanischen Wiedergabe und der Übersetzung, vorbehalten. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re-use of illus trations, broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machine or similar means, and storage in data banks. Under § 54 of the German Copyright Law where copies are made for other than private use a fee is payable to »Verwertungsgesellschaft Wort«, Munich. BUT_OSCE_2011_7311-7.indd 4 13.02.12 08:52 Contents Audronius -

Worldreport | 2017

H U M A N R I G H T S WORLD REPORT|2017 WATCH EVENTS OF 2016 H U M A N R I G H T S WATCH WORLD REPORT 2017 EVENTS OF 2016 Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1-60980-734-4 Front cover photo: Men carrying babies make their way through the rubble of destroyed buildings after an airstrike on the rebel-held Salihin neighborhood of Syria’s northern city of Aleppo, September 2016. © 2016 Ameer Alhalbi/Agence France-Presse-Getty Images Back cover photo: Women and children from Honduras and El Salvador who crossed into the United States from Mexico wait after being stopped in Granjeno, Texas, June 2014. © 2014 Eric Gray/Associated Press Cover and book design by Rafael Jiménez www.hrw.org Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Europe and Central Asia division (then known as Helsinki Watch). Today, it also includes divisions covering Africa; the Americas; Asia; Europe and Central Asia; and the Middle East and North Africa; a United States program; thematic divisions or programs on arms; business and human rights; children’s rights; disability rights; health and human rights; international justice; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights; refugees; women’s rights; and emergencies. -

Tajikistan by Payam Foroughi

Tajikistan by Payam Foroughi Capital: Dushanbe Population: 6.9 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$1,950 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Electoral Process 5.25 5.25 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 Civil Society 5.00 5.00 5.00 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.00 Independent Media 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.00 5.75 5.75 Governance* 6.00 6.00 5.75 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 Judicial Framework and Independence 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 Corruption 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 5.63 5.63 5.71 5.79 5.93 5.96 6.07 6.14 6.14 6.14 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Religious and Belief Prisoners in Over 20 Countries

Religious and Belief Prisoners in over 20 Countries Special Focus Torture and Detention Conditions World Annual Report 2016 Human Rights Without Frontiers International 2016 World Annual Report Religious and Belief Prisoners in over 20 Countries Special Focus Torture and Detention Conditions Human Rights Without Frontiers calls upon the EU to implement its Guidelines on Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB) in order to request the release of peaceful FoRB prisoners Human Rights Without Frontiers documented over 2200 cases of imprisonment in 2016 in a Database available at http://hrwf.eu/forb/forb-and-blasphemy-prisoners-list/ Willy Fautré Dr Mark Barwick With Elisabetta Baldassini, Colin Forber, Matthew Gooch, Nicolas Handford, Lea Perekrests, Perle Rochette, Elisa Van Ruiten, and Lauren Vidler Brussels, 1 March 2017 Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Copyright Human Rights Without Frontiers International. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Human Rights Without Frontiers International. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of this publication should be mailed to the address below. Human Rights Without Frontiers International Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel./ Fax: +32-2-3456145 Website: http://www.hrwf.eu Email: [email protected] Contents CONTENTS .............................................................................................................................. -

Promises to Keep: Diplomatic Assurances Against Torture in US Terrorism Transfers • 9 Summary & Key Recommendations

PROMISES TO KEEP Diplomatic Assurances Against Torture in US Terrorism Transfers Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute DECEMBER 2010 PROMISES TO KEEP Diplomatic Assurances Against Torture in US Terrorism Transfers Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Naureen Shah and edited by Peter Rosenblum. Contributing writers, researchers and editors from the 2009-2010 Human Rights Clinic include Leslie Hannay, Tarek Ismail, Alice Izumo, Lisa Knox and Kate Stinson. Contributing researchers from the 2008-2009 Clinic include Meera Shah, Hiba Hafiz, Aliza Hochman, Alissa King and Kate Morris. Students in the Clinic have pursued aspects of the work that lead to this report from 2003 to the present. Production was coordinated by Greta Moseson and Tarek Ismail. This report was designed by Hatty Lee. We thank all of the individuals and organizations who provided valuable input and in some cases were kind enough of to review particular sections, including Silvia Casale, Paul Champ, Steve Kostas, Bryan Lonegan, Eric Metcalfe, Brittney Nystrom, John Parry and Amrit Singh. ISBN: 978-0-615-43177-2 Human Rights Institute 435 W 116th Street New York, NY 10027 212-854-3138 www.law.columbia.edu/human-rights-institute PROMISES TO KEEP: ASSURANCES AGAINST TORTURE IN US TERRORISM TRANSFERS Summary & Key Recommendations 8 Recommendations 23 Part I. US Transfer and Assurances Practices 26 Chapter 1: US Government Resistance to Disclosure & the Prospect for Reform 26 2009 Inter-Agency Task Force Recommendations 26 Benefits and Costs of US Non-Disclosure 27 Chapter 2: Assurances in US Law & Practice 32 US Law on Transfer & Assurances 32 US State Department Role in Negotiating & Evaluating Assurances 33 Transfer Decision-Making by US Agencies 37 Assurances in Transfers from Guantánamo 38 Assurances in Transfers in Afghanistan 42 Assurances in Extradition & Deportation Cases 47 Renditions to Justice & “Extraordinary Renditions” 53 Part II. -

Release of Guantanamo Detainees Into the United State

Approved for release by ODNI on 3-21-2016, FOIA Case DF-2015-0011 O UNCLASSIFIED//FOR PUBLIC RELEASE --SESRE-T-lft.. H3F0RN- Final Dispositions as of January 22, 2010 Guantanamo Review Dispositions Country ISN Name Decision of Origin AF 4 Abdul Haq Wasiq Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 6 Mullah Norullah Noori Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 7 Mullah Mohammed Fazl Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 560 Haji Wali Muhammed Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war, subject to further review by the Principals prior to the detainee's transfer to a detention facility in the United States. AF 579 Khairullah Said Wali Khairkhwa Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 753 Abdul Sahir Referred for prosecution. AF 762 Obaidullah Referred for prosecution. AF 782 Awai Gui Continued deten_tion pursuant to the Authorization for Use· of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 832 Mohammad Nabi Omari Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 850 Mohammed Hashim Transfer to a country outside the United States that will implement appropriate security measures. -

Closing Guantanamo: the National Security, Fiscal, and Human Rights Implications

S. HRG. 113–872 CLOSING GUANTANAMO: THE NATIONAL SECURITY, FISCAL, AND HUMAN RIGHTS IMPLICATIONS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 24, 2013 Serial No. J–113–22 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( CLOSING GUANTANAMO: THE NATIONAL SECURITY, FISCAL, AND HUMAN RIGHTS IMPLICATIONS S. HRG. 113–872 CLOSING GUANTANAMO: THE NATIONAL SECURITY, FISCAL, AND HUMAN RIGHTS IMPLICATIONS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 24, 2013 Serial No. J–113–22 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–148 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont, Chairman DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa, Ranking Member CHUCK SCHUMER, New York ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah DICK DURBIN, Illinois JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN CORNYN, Texas AL FRANKEN, Minnesota MICHAEL S. LEE, Utah CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware TED CRUZ, Texas RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut JEFF FLAKE, Arizona MAZIE HIRONO, Hawaii KRISTINE LUCIUS, Chief Counsel and Staff Director KOLAN DAVIS, Republican Chief Counsel and Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS DICK DURBIN, Illinois, Chairman AL FRANKEN, Minnesota TED CRUZ, Texas, Ranking Member CHRISTOPHER A. -

Amnesty International Report 2015/16 the State of the World’S Human Rights

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. Amnesty International’s mission is to conduct research and take action to prevent and end grave abuses of all human rights – civil, political, social, cultural and economic. From freedom of expression and association to physical and mental integrity, from protection from discrimination to the right to housing – these rights are indivisible. Amnesty International is funded mainly by its membership and public donations. No funds are sought or accepted from governments for investigating and campaigning against human rights abuses. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Amnesty International is a democratic movement whose major policy decisions are taken by representatives from all national sections at International Council Meetings held every two years. Check online for current details. First published in 2016 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is International’s work and Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton licensed under a Creative concerns through 2015. Street, London WC1X 0DW Commons (attribution, non- The absence of an entry in this United Kingdom commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or international 4.0) licence. © Amnesty International 2016 territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/lice human rights violations of Index: POL 10/2552/2016 nses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International ISBN: 978-0-86210-492-4 For more information please visit have taken place there during the A catalogue record for this book the permissions page on our year. -

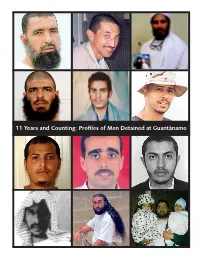

11 Years and Counting: Profiles of Men Detained at Guantánamo 11 Years and Counting: Profiles of Men Detained at Guantánamo

11 Years and Counting: Profiles of Men Detained at Guantánamo 11 Years and Counting: Profiles of Men Detained at Guantánamo Name and Internment Serial Number (ISN) Citizenship Shaker Aamer (ISN 239) Yemen Umar Abdulayev (ISN 257) Tajikistan Ahmed Abdul Aziz (ISN 757) Mauritania Abu Zubaydah (ISN 10016) Palestinian Territories Ahmed Ajam (ISN 326) Syria Mohammed al-Adahi (ISN 33) Yemen Sa’ad Muqbil Al-Azani (ISN 575); Jalal bin Amer (ISN 564) and Suhail Abdu Anam (ISN 569) Yemen Ghaleb al-Bihani (ISN 128) Yemen Ahmed al-Darbi (ISN 768) Saudi Arabia Mohammed al-Hamiri (ISN 249) Yemen Sharqawi Ali al-Hajj (ISN 1457) Yemen Sanad al-Kazimi (ISN 1453) Yemen Musa’ab al Madhwani (ISN 839) Yemen Hussain Almerfedi (ISN 1015) Yemen Saad Al Qahtani (ISN 200) Saudi Arabia Abdul Rahman Al-Qyati (ISN 461) Yemen 1 Ali Hussein al-Shaaban (ISN 327) Syria Djamel Ameziane (ISN 310) Algeria Tariq Ba Odah (ISN 178) Yemen Ahmed Belbacha (290) Algeria Jihad Dhiab (ISN 722) Syria Fahd Ghazy (ISN 26) Yemen Saeed Mohammed Saleh Hatim (ISN 255) Yemen Obaidullah (ISN 762) Afghanistan Mohamedou Ould Slahi (ISN 760) Mauritania Mohammed Tahamuttan (ISN 684) Palestinian Territories * The following profiles are intended to provide the Commission with personal information about the men at Guantánamo because the United States will not grant the Commissioners access to the prisoners themselves. The information has been taken from phone calls, letters, or in-person interviews. None of the information herein has been deemed "classified" by the U.S Government. Where possible, original source material has been included (usually transcribed for ease of reading).