How NRDC Helped Save the Ozone Layer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Influence of Wildfires on Aerosol Chemistry in the Western US

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2477–2493, 2017 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/17/2477/2017/ doi:10.5194/acp-17-2477-2017 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Regional influence of wildfires on aerosol chemistry in the western US and insights into atmospheric aging of biomass burning organic aerosol Shan Zhou1, Sonya Collier1, Daniel A. Jaffe2,3, Nicole L. Briggs2,3,4, Jonathan Hee2,3, Arthur J. Sedlacek III5, Lawrence Kleinman5, Timothy B. Onasch6, and Qi Zhang1 1Department of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA 2School of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, University of Washington Bothell, Bothell, WA 98011, USA 3Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 4Gradient, Seattle, WA 98101, USA 5Environmental and Climate Sciences Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973, USA 6Aerodyne Research Inc., Billerica, MA 01821, USA Correspondence to: Qi Zhang ([email protected]) Received: 19 September 2016 – Discussion started: 23 September 2016 Revised: 2 January 2017 – Accepted: 19 January 2017 – Published: 16 February 2017 Abstract. Biomass burning (BB) is one of the most im- OA mass); and a highly oxidized BBOA-3 (O = C D 1.06; portant contributors to atmospheric aerosols on a global 31 % of OA mass) that showed very low volatility with only scale, and wildfires are a large source of emissions that im- ∼ 40 % mass loss at 200 ◦C. The remaining 32 % of the OA pact regional air quality and global climate. As part of the mass was attributed to a boundary layer (BL) oxygenated Biomass Burning Observation Project (BBOP) field cam- OA (BL-OOA; O = C D 0.69) representing OA influenced by paign in summer 2013, we deployed a high-resolution time- BL dynamics and a low-volatility oxygenated OA (LV-OOA; of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-AMS) coupled with O = C D 1.09) representing regional aerosols in the free tro- a thermodenuder at the Mt. -

Impacts of Anthropogenic Aerosols on Fog in North China Plain

BNL-209645-2018-JAAM Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres RESEARCH ARTICLE Impacts of Anthropogenic Aerosols on Fog in North China Plain 10.1029/2018JD029437 Xingcan Jia1,2,3 , Jiannong Quan1 , Ziyan Zheng4, Xiange Liu5,6, Quan Liu5,6, Hui He5,6, 2 Key Points: and Yangang Liu • Aerosols strengthen and prolong fog 1 2 events in polluted environment Institute of Urban Meteorology, Chinese Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China, Brookhaven National Laboratory, • Aerosol effects are stronger on Upton, NY, USA, 3Key Laboratory of Aerosol-Cloud-Precipitation of China Meteorological Administration, Nanjing University microphysical properties than of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 4Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, macrophysical properties Beijing, China, 5Beijing Weather Modification Office, Beijing, China, 6Beijing Key Laboratory of Cloud, Precipitation and • Turbulence is enhanced by aerosols during fog formation and growth but Atmospheric Water Resources, Beijing, China suppressed during fog dissipation Abstract Fog poses a severe environmental problem in the North China Plain, China, which has been Supporting Information: witnessing increases in anthropogenic emission since the early 1980s. This work first uses the WRF/Chem • Supporting Information S1 model coupled with the local anthropogenic emissions to simulate and evaluate a severe fog event occurring Correspondence to: in North China Plain. Comparison of the simulations against observations shows that WRF/Chem well X. Jia and Y. Liu, reproduces the general features of temporal evolution of PM2.5 mass concentration, fog spatial distribution, [email protected]; visibility, and vertical profiles of temperature, water vapor content, and relative humidity in the planetary [email protected] boundary layer throughout the whole period of the fog event. -

The Impact of Aerosols on the Color and Brightness of the Sun and Sky

The Impact of Aerosols on the Color and Brightness of the Sun and Sky Stanley David Gedzelman * Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and NOAA CREST Center, City College of New York 1. INTRODUCTION and brightness that capture the main aspects of scattering behavior. SKYCOLOR is such a model. Long before the climatic impact of aerosols was It is available at www.sci.ccny.cuny.edu/~stan recognized, their impact on the appearance of the (then click on Atmospheric Optics). In §2, sky was considered obvious (Minnaert, 1954). SKYCOLOR is briefly described and in §3 it is The sky is deepest blue when air is clean and dry, applied to situations that indicate how sky color but it always whitens toward the horizon when the and brightness provide information about the sun is high in the sky and reddens at the horizon aerosol and ozone content of the atmosphere. during twilight. Hazy skies are typically brighter, This shows its relevance to climate problems. particularly near the sun, but less blue, and may even take on pastel or earth tones. At twilight, 2. SKYCOLOR: THE MODEL aerosol laden skies can exhibit rich red colors near the horizon, and volcanic aerosol particles SKYCOLOR is a simplified model of sky color and may even turn the twilight sky crimson far above brightness in the vertical plane including the sun the horizon. and the observer (Gedzelman, 2005). Model Sky colors result from a combination of factors skylight consists of sunbeams that are scattered including the solar spectrum and zenith angle, the toward the observer, but depleted by scattering scattering properties of air molecules and aerosol and absorption in the Chappuis bands of ozone. -

WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality : Selected Pollutants

WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: This book presents WHO guidelines for the protection of pub- lic health from risks due to a number of chemicals commonly present in indoor air. The substances considered in this review, i.e. benzene, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, naphthalene, nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (especially benzo[a]pyrene), radon, trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethyl- ene, have indoor sources, are known in respect of their hazard- ousness to health and are often found indoors in concentrations of health concern. The guidelines are targeted at public health professionals involved in preventing health risks of environmen- SELECTED CHEMICALS SELECTED tal exposures, as well as specialists and authorities involved in the design and use of buildings, indoor materials and products. POLLUTANTS They provide a scientific basis for legally enforceable standards. World Health Organization Regional Offi ce for Europe Scherfi gsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Tel.: +45 39 17 17 17. Fax: +45 39 17 18 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.euro.who.int WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health, Bonn Office, WHO Regional Office for Europe coordinated the development of these WHO guidelines. Keywords AIR POLLUTION, INDOOR - prevention and control AIR POLLUTANTS - adverse effects ORGANIC CHEMICALS ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE - adverse effects GUIDELINES ISBN 978 92 890 0213 4 Address requests for publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for per- mission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Ozone: Good up High, Bad Nearby

actions you can take High-Altitude “Good” Ozone Ground-Level “Bad” Ozone •Protect yourself against sunburn. When the UV Index is •Check the air quality forecast in your area. At times when the Air “high” or “very high”: Limit outdoor activities between 10 Quality Index (AQI) is forecast to be unhealthy, limit physical exertion am and 4 pm, when the sun is most intense. Twenty minutes outdoors. In many places, ozone peaks in mid-afternoon to early before going outside, liberally apply a broad-spectrum evening. Change the time of day of strenuous outdoor activity to avoid sunscreen with a Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of at least 15. these hours, or reduce the intensity of the activity. For AQI forecasts, Reapply every two hours or after swimming or sweating. For check your local media reports or visit: www.epa.gov/airnow UV Index forecasts, check local media reports or visit: www.epa.gov/sunwise/uvindex.html •Help your local electric utilities reduce ozone air pollution by conserving energy at home and the office. Consider setting your •Use approved refrigerants in air conditioning and thermostat a little higher in the summer. Participate in your local refrigeration equipment. Make sure technicians that work on utilities’ load-sharing and energy conservation programs. your car or home air conditioners or refrigerator are certified to recover the refrigerant. Repair leaky air conditioning units •Reduce air pollution from cars, trucks, gas-powered lawn and garden before refilling them. equipment, boats and other engines by keeping equipment properly tuned and maintained. During the summer, fill your gas tank during the cooler evening hours and be careful not to spill gasoline. -

Aerosol Emissions from Prescribed Fires in The

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres RESEARCH ARTICLE Aerosol emissions from prescribed fires in the United 10.1002/2014JD021848 States: A synthesis of laboratory Key Points: and aircraft measurements • Laboratory experiments represent aircraft measurements reasonably well A. A. May1,2, G. R. McMeeking1,3, T. Lee1,4, J. W. Taylor5, J. S. Craven6, I. Burling7,8, A. P. Sullivan1, • Black carbon emissions in inventories 8 1 5 5 9 6 8 may require upward revision S. Akagi , J. L. Collett Jr. , M. Flynn , H. Coe , S. P. Urbanski , J. H. Seinfeld , R. J. Yokelson , and S. M. Kreidenweis1 1Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, 2Now at Department of Civil, Correspondence to: Environmental, and Geodetic Engineering, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA, 3Now at Droplet Measurement S. M. Kreidenweis, Technologies, Inc., Boulder, Colorado, USA, 4Now at Department of Environmental Science, Hankuk University of Foreign [email protected] Studies, Seoul, South Korea, 5Centre for Atmospheric Science, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 6Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA, 7Now at Cytec Canada, Citation: Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, 8Department of Chemistry, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA, 9Fire Sciences May, A. A., et al. (2014), Aerosol emissions Laboratory, United States Forest Service, Missoula, Montana, USA from prescribed fires in the United States: A synthesis of laboratory and aircraft measurements, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., Abstract Aerosol emissions from prescribed fires can affect air quality on regional scales. Accurate 119,11,826–11,849, doi:10.1002/ 2014JD021848. representation of these emissions in models requires information regarding the amount and composition of the emitted species. -

WILDFIRE SMOKE FACTSHEET Indoor Air Filtration

WILDFIRE SMOKE FACTSHEET Indoor Air Filtration When wildfre smoke gets inside your home it can make your indoor air unhealthy, but there are steps you can take to protect your health and improve the air quality in your home. Reducing indoor sources of pollution is a major step toward lowering the concentrations of particles indoors. For example, avoid burning candles, smoking tobacco products, using aerosol products, and avoid using a gas or wood-burning stove or freplace. Another step is air fltration. This fact sheet discusses efective options for fltering your home’s indoor air to reduce indoor air pollution. Filtration Options flter (MERV 13-16) can reduce indoor particles by as much There are two efective options for improving air f ltration as 95 percent. Filters with a High Ef ciency Particulate in the home: 1) upgrading the central air system f lter, and 2) using high efciency portable air cleaners. Before Air (HEPA) rating, (or MERV 17-20) are the most efcient. You may need to consult with a local heating and air discussing fltration options, it is important to understand the basics of f lter ef ciency. technician or the manufacturer of your central air system to confrm which (or if ) high ef ciency flters will work Filter Ef ciency with your system. If you can’t switch to a more efcient The most common industry standard for f lter ef ciency is the Minimum Ef ciency Reporting Value, or “MERV flter, running the system continuously by switching the rating.” The MERV scale for residential flters ranges from 1 thermostat fan from “Auto” to “On” has been shown to reduce particle concentrations by as much as 24 percent. -

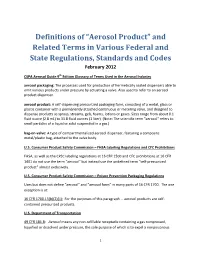

Aerosol Product” and Related Terms in Various Federal and State Regulations, Standards and Codes February 2012

Definitions of “Aerosol Product” and Related Terms in Various Federal and State Regulations, Standards and Codes February 2012 CSPA Aerosol Guide 9th Edition Glossary of Terms Used in the Aerosol Industry aerosol packaging: The processes used for production of hermetically sealed dispensers able to emit various products under pressure by actuating a valve. Also used to refer to an aerosol product dispenser. aerosol product: A self‐dispensing pressurized packaging form, consisting of a metal, glass or plastic container with a permanently attached continuous or metering valve, and designed to dispense products as sprays, streams, gels, foams, lotions or gases. Sizes range from about 0.1 fluid ounce (2.8 mL) to 33.8 fluid ounces (1 liter). (Note: The scientific term "aerosol" refers to small particles of a liquid or solid suspended in a gas.) bag‐on‐valve: A type of compartmentalized aerosol dispenser, featuring a composite metal/plastic bag, attached to the valve body. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission – FHSA Labeling Regulations and CFC Prohibitions FHSA, as well as the CPSC labeling regulations at 16 CFR 1500 and CFC prohibitions at 16 CFR 1401 do not use the term “aerosol” but instead use the undefined term “self‐pressurized product” almost exclusively. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission – Poison Prevention Packaging Regulations Uses but does not define “aerosol” and “aerosol form” in many parts of 16 CFR 1700. The one exception is at: 16 CFR 1700.15(b)(2)(ii): For the purposes of this paragraph … aerosol products are self‐ contained pressurized products. U.S. Department of Transportation 49 CFR 181.8: Aerosol means any non‐refillable receptacle containing a gas compressed, liquefied or dissolved under pressure, the sole purpose of which is to expel a nonpoisonous 1 (other than a Division 6.1 Packing Group III material) liquid, paste, or powder and fitted with a self‐closing release device allowing the contents to be ejected by the gas. -

Aerosol Cans Are Regulations Are Found in Made of Recyclable Steel Or Aluminum and Can Be Easily Managed As Chapters NR 600-679 Scrap Metal When Empty

Aerosol Can Management Guidance on Hazardous Waste Requirements Introduction Aerosol spray cans contain products and propellants under pressure that can be dispensed as spray, mist or foam. Common products include Hazardous waste insecticides, cooking sprays, solvents and paints. Most aerosol cans are regulations are found in made of recyclable steel or aluminum and can be easily managed as chapters NR 600-679 scrap metal when empty. However, when aerosol cans are unusable or of the Wisconsin cannot be emptied due to defective or broken spray nozzles the remaining Administrative Code. liquids, vapors, or even the can itself, may be hazardous waste and subject to regulation. Waste aerosol cans cannot be managed as universal waste in Wisconsin. While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and some states allow aerosol cans to be managed as universal waste this regulatory allowance has not been adopted in Wisconsin at this time and aerosol cans continue to require waste determinations and proper management. This publication provides waste management guidance to businesses generating hazardous waste aerosol cans. The following sections will define and discuss the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act “RCRA empty” determinations, acute hazardous waste determinations, storage requirements, puncturing requirements and hazardous waste reduction recommendations. “RCRA empty” determinations The first step to determine management requirements is to evaluate whether the waste aerosol cans are “RCRA empty” according to s. NR 661.0007, Wis. Adm. Code, and the U.S EPA’s RCRA definition of empty containers. Waste aerosol cans are “RCRA empty” when they meet all criteria listed below: 1. The aerosol cans must contain no compressed propellant (i.e., the aerosol cans release no pressure through an open, working valve). -

Aerosol-Ozone Correlations During Dust Transport Episodes

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 4, 1201–1215, 2004 www.atmos-chem-phys.org/acp/4/1201/ Atmospheric SRef-ID: 1680-7324/acp/2004-4-1201 Chemistry and Physics Aerosol-ozone correlations during dust transport episodes P. Bonasoni1, P. Cristofanelli1, F. Calzolari1, U. Bonafe`1, F. Evangelisti1, A. Stohl2, S. Zauli Sajani3, R. van Dingenen4, T. Colombo5, and Y. Balkanski6 1National Research Council, Institute for Atmospheric Science and Climate, via Gobetti 101, 40129, Bologna, Italy 2Cooperative Institute for Research in the Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado/NOAA Aeronomy Laboratory, USA 3Agenzia Regionale Prevenzione e Ambiente dell’Emilia-Romagna, Struttura Tematica Epidemiologia Ambientale, Modena, Italy 4Joint Research Center, Ispra, Italy 5Ufficio Generale per la Meteorologia, Pratica di Mare, Roma, Italy 6Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environment, Gif-Sur-Yvette Cedex, France Received: 3 February 2004 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 16 April 2004 Revised: 14 July 2004 – Accepted: 27 July 2004 – Published: 3 August 2004 Abstract. Its location in the Mediterranean region and and rural areas showed that during the greater number of the ◦ 0 its physical characteristics render Mt. Cimone (44 11 N, considered dust events, significant PM10 increases and ozone 10◦420 E), the highest peak of the Italian northern Apennines decreases have occurred in the Po valley. (2165 m asl), particularly suitable to study the transport of air masses from the north African desert area to Europe. During these northward transports 12 dust events were registered in measurements of the aerosol concentration at the station dur- 1 Introduction ing the period June–December 2000, allowing the study of the impact of mineral dust transports on free tropospheric Mineral dust is one of the greatest sources of natural aerosol ozone concentrations, which were also measured at Mt. -

Variations of Aerosol Optical Depth and Angstrom Parameters at a Suburban Location in Iran During 2009–2010

Variations of aerosol optical depth and Angstrom parameters at a suburban location in Iran during 2009–2010 M Khoshsima1,∗, A A Bidokhti2 and F Ahmadi-Givi2 1Department of Meteorology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. 2Institute of Geophysics, University of Tehran, Tehran, P. O. Box 14155-6466, Iran. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Solar irradiance is attenuated spectrally when passing through the earth’s atmosphere and it is strongly dependent on sky conditions, cleanliness of the atmosphere, composition of aerosols and gaseous con- stituents. In this paper, aerosol optical properties including aerosol optical depth (AOD), Angstrom exponent (α) and Angstrom turbidity coefficient (β) have been investigated during December 2009 to October 2010, in a suburban area of Zanjan (36◦N, 43◦E, 1700 m), in the north–west of Iran, using meteorological and sun photometric data. Results show that turbidity varies on all time scales, from the seasonal to hourly, because of changes in the atmospheric meteorological parameters. The values of α range from near zero to 1.67. The diurnal variation of AOD in Zanjan is about 15%. The diurnal vari- ability of AOD, showed a similar variation pattern in spring (including March, April, May) and winter (December, January, February) and had a different variation pattern in summer (June, July, August) and autumn (September and October). During February, spring and early summer winds transport continental aerosols mostly from the Iraq (dust events) and cause the increase of beta and turbidity of atmosphere of Zanjan. 1. Introduction On a global scale, the natural sources of aero- sols are more important than the anthropogenic Suspended aerosol particles in the atmosphere, apart aerosols, but regionally anthropogenic aerosols are from health effects and indirect effects on clouds, significant (Coakley et al. -

Increased Inorganic Aerosol Fraction Contributes to Air Pollution and Haze in China

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 5881–5888, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-5881-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Increased inorganic aerosol fraction contributes to air pollution and haze in China Yonghong Wang1,2, Yuesi Wang1,6,8, Lili Wang1, Tuukka Petäjä2,3, Qiaozhi Zha2, Chongshui Gong1,4, Sixuan Li7, Yuepeng Pan1, Bo Hu1, Jinyuan Xin1, and Markku Kulmala2,3,5 1State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry (LAPC), Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research/Physics, Faculty of Science, P.O. Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 3Joint international research Laboratory of Atmospheric and Earth SysTem sciences (JirLATEST), Nanjing University, Nanjing, China 4Institute of Arid meteorology, China Meteorological Administration, Lanzhou, China 5Aerosol and Haze Laboratory, Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Soft Matter Science and Engineering, Beijing University of Chemical Technology (BUCT), Beijing, China 6Centre for Excellence in Atmospheric Urban Environment, Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Science, Xiamen, Fujian, China 7State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics (LASG), Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 8University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Correspondence: Yuesi Wang ([email protected]), Lili Wang ([email protected]) and Markku Kulmala (markku.kulmala@helsinki.fi) Received: 12 September 2018 – Discussion started: 21 September 2018 Revised: 22 March 2019 – Accepted: 10 April 2019 – Published: 3 May 2019 Abstract. The detailed formation mechanism of an increased 1 Introduction number of haze events in China is still not very clear.